CONTENTS May/June 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

Photography and Cinema

Photography and Cinema David Campany Photography and Cinema EXPOSURES is a series of books on photography designed to explore the rich history of the medium from thematic perspectives. Each title presents a striking collection of approximately80 images and an engaging, accessible text that offers intriguing insights into a specific theme or subject. Series editors: Mark Haworth-Booth and Peter Hamilton Also published Photography and Australia Helen Ennis Photography and Spirit John Harvey Photography and Cinema David Campany reaktion books For Polly Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2008 Copyright © David Campany 2008 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Campany, David Photography and cinema. – (Exposures) 1. Photography – History 2. Motion pictures – History I. Title 770.9 isbn–13: 978 1 86189 351 2 Contents Introduction 7 one Stillness 22 two Paper Cinema 60 three Photography in Film 94 four Art and the Film Still 119 Afterword 146 References 148 Select Bibliography 154 Acknowledgements 156 Photo Acknowledgements 157 Index 158 ‘ . everything starts in the middle . ’ Graham Lee, 1967 Introduction Opening Movement On 11 June 1895 the French Congress of Photographic Societies (Congrès des sociétés photographiques de France) was gathered in Lyon. Photography had been in existence for about sixty years, but cinema was a new inven- tion. -

Julia SVETLICHNAJA.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Artistic practices & democratic politics: towards the markers of uncertainty from counter-hegemonic positions to plural hegemonies Julia Svetlichnaja School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2011. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Artistic Practices & Democratic Politics: Towards the Markers of Uncertainty From Counter-Hegemonic Positions to Plural Hegemonies A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Julia Svetlichnaja May 2011 2 Contents Abstract -

Beth Michael-Fox Thesis for Online

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Present and Accounted For: Making Sense of Death and the Dead in Late Postmodern Culture Bethan Phyllis Michael-Fox ORCID: 0000-0002-9617-2565 Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT STATEMENT No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work. I confirm that no work previously submitted for credit has been reused verbatim. Any previously submitted work has been revised, developed and recontextualised relevant to the thesis. I confirm that no material of this thesis has been published in advance of its submission. I confirm that no third party proof-reading or editing has been used in this thesis. 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Alec Charles for his steadfast support and consistent interest in and enthusiasm for my research. I would also like to thank him for being so supportive of my taking maternity leave and for letting me follow him to different institutions. I would like to thank Professor Marcus Leaning for his guidance and the time he has dedicated to me since I have been registered at the University of Winchester. I would also like to thank the University of Winchester’s postgraduate research team and in particular Helen Jones for supporting my transfer process, registration and studies. -

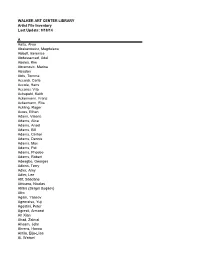

WALKER ART CENTER LIBRARY Artist File Inventory Last Update: 9/18/14

WALKER ART CENTER LIBRARY Artist File Inventory Last Update: 9/18/14 A Aalto, Alvar Abakanowicz, Magdalena Abbott, Berenice Abdessemed, Adel Abeles, Kim Abramovic, Marina Absalon Abts, Tomma Accardi, Carla Accola, Hans Acconci, Vito Achepohl, Keith Ackermann, Franz Ackermann, Rita Ackling, Roger Acres, Ethan Adami, Valerio Adams, Alice Adams, Ansel Adams, Bill Adams, Clinton Adams, Dennis Adams, Mac Adams, Pat Adams, Phoebe Adams, Robert Adeagbo, Georges Adkins, Terry Adler, Amy Adler, Lee Afif, Saadane Africano, Nicolas Afrika (Sergei Bugaev) Afro Agam, Yaacov Agematsu, Yuji Agostini, Peter Agresti, Armand Ah Xian Ahad, Zalmai Ahearn, John Ahrens, Hanno Ahtila, Eija-Liisa Ai, Weiwei Aiken, Ta-coumba Aitchison, Craigie Aitken, Doug Ajay, Abe Akagawa, Kinji Akakce, Haluk Akkerman, Philip al-Hadid, Diana Albenda, Ricci Alberola, Jean Michel Albers, Anni Albers, Josef Alberti, Donald Albertini, Bill Albin-Guillot, Laure Albrecht, Jurgen Albright, Ivan Albrizio, Humbert Albuquerque, Lita Aldrich, Richard Aldrich, Stephen Alechinsky, Pierre Alexa, Cristian Alexander, Dorothy Alexander, John Alexander, Peter Alexis, Grady Alexis, Michel Alford, Kael Ali, Layla Ali, Maria R. Allain, Rene Pierre Allen, Julie Allen, Terry Allington, Edward Allner, Walter Allora, Jennifer & Calzadilla, Guillermo Allyn, Jerri Almog, Diti Almond, Darren Alpern, Merry Alsop, Adele Alsop, Will Alt, Otmar Altaf, Navjot Altenburger, Stefan Altfest, Ellen Althoff, Kai Altmejd, David Altoon, John Alvarez Bravo, Manuel Alvarez, Candida Alvarez, D-L Alys, Francis Amano, Yoshitaka -

Kat Gollock the Filth, and the Fury Mark Pawson Comic & Zine

cross currents in culture variant number 43 spring 2012 free Kat Gollock The Filth, and the Fury Mark Pawson Comic & Zine Reviews Jorge Ribalta Towards a New Documentalism Emma Louise Briant If... On Martial Values and Britishness Tom Coles “Organise your mourning” Ellen Feiss Santiago Sierra... Ethics and the political efficacy of citationTom Jennings The Poverty of Imagination Rosemary Meade “Our country’s calling card”Joanne Laws Generation Bailout Friendofzanetti The Housing Monster 2 | variant 43 | spring 2012 Variant 43 Spring 2012 Variant engages in the Editorial Group contents examination and critique of The Filth, and the Fury editor/ administration: society and culture, drawing Leigh French Kat Gollock from knowledge across the 3 arts, social sciences and co-editors: humanities, as an approach to Gordon Asher Comic & Zine Reviews creative cultural practice and John Beagles as something distinct from Lisa Bradley Mark Pawson 7 promotional culture. Neil Gray It is an engagement of Gesa Helms practice which seeks to publicly Daniel Jewesbury Towards a New Documentalism participate in and understand Owen Logan Jorge Ribalta 10 culture ‘in the round’. That is, Advisory Group in the many and various ways Monika Vykoukal culture exemplifies, illuminates Simon Yuill If.... and engages with larger societal Kirsten Forkert On Martial Values and Britishness processes. 12 We contend it is constructive Design Kevin Hobbs Emma Louise Briant and essential to place articles which address the multiple ISSN: 09548815 facets of culture alongside ‘Organise your mourning’ Printers articles on issues that inform Spectator Newspapers, Bangor, Tom Coles or have consequences for 19 Co. Down, N. Ireland BT20 4AF the very production and subject of knowledge and its Contribute Ethics and the political efficacy of communication. -

Noordegraaf DEF.Indd 1 08-01-13 14:33 FRAMING FILM

FRAMING ET AL. (EDS.) NOORDEGRAAF JULIA NOORDEGRAAF, COSETTA G. SABA, FILM BARBARA LE MAÎTRE, VINZENZ HEDIGER (EDS.) PRESERVING AND EXHIBITING MEDIA ART PRESERVING AND EXHIBITING MEDIA ART Challenges and Perspectives This important and fi rst-of-its-kind collection addresses the Julia Noordegraaf is AND EXHIBITING MEDIA ART PRESERVING emerging challenges in the fi eld of media art preservation and Professor of Heritage and exhibition, providing an outline for the training of professionals in Digital Culture at the Univer- this fi eld. Since the emergence of time-based media such as fi lm, sity of Amsterdam. video and digital technology, artists have used them to experiment Cosetta G. Saba is Associate with their potential. The resulting artworks, with their basis in Professor of Film Analysis rapidly developing technologies that cross over into other domains and Audiovisual Practices in such as broadcasting and social media, have challenged the tradi- Media Art at the University tional infrastructures for the collection, preservation and exhibition of Udine. of art. Addressing these challenges, the authors provide a historical Barbara Le Maître is and theoretical survey of the fi eld, and introduce students to the Associate Professor of challenges and di culties of preserving and exhibiting media art Theory and Aesthetics of through a series of fi rst-hand case studies. Situated at the threshold Static and Time-based Images at the Université Sorbonne between archival practices and fi lm and media theory, it also makes nouvelle – Paris 3. a strong contribution to the growing literature on archive theory Vinzenz Hediger is and archival practices. Professor of Film Studies at the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. -

Dan Flavin (1933-1996)

David Zwirner This document was updated November 14, 2018. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact: [email protected] DAN FLAVIN (1933-1996) SELECTED EXHIBITION HISTORY This selection of exhibitions lists only those that Dan Flavin or the Estate of Dan Flavin was involved in as installer, lender, or consultant. The list of group exhibitions also includes a number of historically important shows and additional exhibitions. Capitalization and punctuation of solo exhibition titles reflect the artist’s preference. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1961 “d. n. flavin: constructions and watercolors.” Judson Gallery, New York. May 8–June 5. 1964 “dan flavin: some light.” Kaymar Gallery, New York. March 5–29. “dan flavin: fluorescent light.” Green Gallery, New York. November 18–December 12. 1965 Fine Arts Building, Ohio State University, Columbus. April–May. 1966 Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, Cologne. Opened September 16. Brochure. Nicholas Wilder Gallery, Los Angeles. December. 1967 Kornblee Gallery, New York. January 7–February 2. Galleria Sperone, Milan. February 14–March 15. This exhibition was not recognized by the artist.1 Kornblee Gallery, New York. October 7–November 8. 1 See fluorescent light, etc. from Dan Flavin/lumière fluorescente, etc. par Dan Flavin, exh. cat. (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada; Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1969), p. 252. “Dan Flavin: alternating pink and ‘gold.’” Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. December 9, 1967– January 14, 1968. Catalogue. 1968 “Dan Flavin: lampade fluorescente gialle.” Galleria Sperone, Turin. March 14–April 10. Brochure. Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Munich. May 9–June 5. “Dan Flavin: an exposition of fluorescent light.” Hetzel Union Building Gallery, Pennsylvania State University, University Park. -

Pauline Boty and the Predicament of the Woman Artist in the British Pop Art Movement Suetate Volume One

GENDERING THE FIELD: PAULINE BOTY AND THE PREDICAMENT OF THE WOMAN ARTIST IN THE BRITISH POP ART MOVEMENT SUETATE VOLUME ONE (of two) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Bath Spa University College School of English and Creative Studies, Bath Spa University College. November 2004 Volume One Contents Page i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page ii AUTHOR'S PREFACE Page iii ABSTRACT Page 1 INTRODUCTION (statement of objectives) Page 8 CHAPTER ONE: METHODOLOGY and CRITICAL REVIEW OF LITERATURE page 8 Part One: Methodology page 8 Historiography page 10 A feminist historical materialism page 12 Mapping the dynamics of the field page 13 The artist's biography: the role of the 'life and works' page 16 Discursive shifts : art historical revisionism and problems in feminism page 17 Part Two: A Critical Review of Literature page 19 Ontological insecurity page 26 The myth of the homogeneous audience page 30 The evacuation of meaning page 36 The detached artist page 37 Multifarious yet gender free readings Page 43 CHAPTER TWO: GENDERING THE FIELD OF PRODUCTION AND DISTRIBUTION page 44 The Royal College of Art : a site for investigation page 45 A masculine ethos page 51 Kudos and gender page 56 Distributive apparatus page 57 The non-commercial sites page 58 The John Moores page 60 The ICA page 61 The Young Contemporaries page 66 Private galleries page 70 A comparison with Fluxus Page 76 CHAPTER THREE: PAULINE BOTY, A GLORIOUS EXCEPTION? page 76 Family -

Play As the Main Event in International and UK Culture James Woudhuysen, De Montfort University

PSI_CT43_24/4 28/4/03 12:34 pm Page 95 Play as the Main Event in International and UK Culture James Woudhuysen, De Montfort University Abstract Play has become a dominant trend in the culture of Western adults. This chapter of Cultural Trends looks at its prevalence and growth. The first section briefly discusses what play is. The second provides an overview of playful varieties of leisure in the US and worldwide, and sums up some of the main trends that have emerged. The third follows the same method in relation to the UK. The fourth section looks at the increasing incidence of play at work, while the final section draws conclusions from the evidence presented. Throughout, special attention is played to the role of information technology in play. Five industries are covered extensively – computer games; gambling; sport; performing arts; and fairs, theme parks and adventure holidays. Attendance at, participation in and paid employment in play constitute three levels of engagement in it. This chapter tries to measure these levels of engagement by bringing together just some of the vast but disparate literature and statistics on play. The range of sources drawn upon is varied. Inspired by the perspectives of writers in economics, politics, sociology and technology, this chapter uses official govern- ment data, and data taken from the business press, to illustrate its ideas. The chapter asks and answers the following three questions: • Does play provide spaces and moments of freedom that, fortunately enough, lie beyond the grasp of market forces? • Is the entertainment provided by play genuinely educational, or does absorption in play instead represent a degraded notion of the Self? • By favouring mass attendance at, mass participation in and mass employment in playful activities, have UK government policies advanced the cause of culture – or have they set it back? PSI_CT43_24/4 28/4/03 12:34 pm Page 96 PSI_CT43_24/4 28/4/03 12:34 pm Page 97 4. -

Culture Vultures

Politicians and policy-makers take every opportunity to talk up the arts’ importance to society. The Arts Council and Vultures Culture Department for Culture, Media and Sport insist that the arts are now not only good in themselves, but are valued for their contribution to the economy, urban regeneration and social inclusion. Arts organisations – large and small – are being asked to think about how their work can support government targets for health, employment, crime, education and community cohesion. Is there actually any evidence to support them? Also, does the growing political interest in the arts compromise their freedom and integrity? Culture Vultures brings together a panel of Culture experts who show that many official claims about the Edited by Munira Mirza economic and social benefits of arts are based on exaggeration, resulting in wasteful and ineffective social policies. Even worse, such political intrusion means that Vultures organisations are drowning under a tidal wave of ‘tick boxes Is UK arts policy damaging the arts? and targets’ in an attempt to measure their social impact. £10 ISBN 0-9551909-0-8 Policy Exchange Clutha House 10 Storey’s Gate Policy Exchange London SW1P 3AY Tel: 020 7340 2650 Edited by www.policyexchange.org.uk Munira Mirza px cultural policy.qxd 19/01/2006 15:26 Page 1 About Policy Exchange Policy Exchange is an independent think tank whose mission is to develop and promote new policy ideas which will foster a free society based on strong communities, personal freedom, limited government, national selfconfidence and an enterprise culture. Registered charity no:1096300. Policy Exchange is committed to an evidencebased approach to policy development. -

Arts Development and Policy in Rural Scotland

Lu, Yu Tonia (2015) Lost in location: arts development and policy in rural Scotland. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/5899/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Lost in Location? Arts Development and Policy in Rural Scotland Yu ‘Tonia’ Lu BA, MA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow College of Creative Arts Centre for Cultural Policy Research January 2014 © Yu Tonia Lu 2014 Abstract 2 Abstract This thesis examines arts development and policy in rural Scotland in recent years. In this formerly unexplored field, it looks at the relationship between arts policy and arts development practice in rural Scotland and the impacts and (dis)connections that the nationwide arts policy has had on arts in rural Scotland, particularly during a period of major change in Scottish arts policy between 2010 and 2013. Nine rural regions with a population density of under 30 people per kilometre2 as of 2009 were selected as the key geographic regions in this research: Dumfries and Galloway, Scottish Borders, Argyll and Bute, Highland, Eileanan Siar (Western Isles), Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands, Moray and Aberdeenshire.