Early Childhood Transition Executive Full Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-2022 School Open House/Meet & Greet Schedule

2021-2022 School Open House/Meet & Greet Schedule HIGH SCHOOL DATE TIME URL Bloomington Graduation School/Adult Learning Monday, August 23, 2021 6:00-7:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/bgs Career Training Fair Open House Monday, August 23, 2021 6:00-7:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/adulted Bloomington High School North Open House Monday, August 23, 2021 6:00-8:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/bhsn Bloomington High School South Open House Wednesday, August 25, 2021 7:00-9:00 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/bhss Academy of Science & Entrepreneurship Wednesday, August 18, 2021 5:30-8:00p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/ase Hoosier Hills Career Center Monday, August 23, 2021 6:00-8:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/hoosierhills MIDDLE SCHOOL DATE TIME URL Tri-North Open House Wednesday, August 11, 2021 6:00-8:00p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/trinorth Batchelor Open House Thursday, August 12, 2021 6:30-8:00 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/batchelor Jackson Creek Open House Wednesday, August 11, 2019 5:30-7:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/jacksoncreek ELEMENTARY DATE TIME URL Arlington Heights Meet the Teacher Tuesday, August 3, 2021 2:30-3:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/arlingtonheights • Open House Tuesday, August 17 2021 5:30-7:00 p.m. Binford Meet the Teacher Tuesday, August 3, 2021 2:00-3:30 p.m. http://www.mccsc.edu/binford • Open House Thursday, August 26, 2021 6:00-7:00 p.m. Childs Meet the Teacher Tuesday, August 3, 2021 2:00-3:00 p.m. -

Academic Open House Map S West Gr Esapeake a Parking

ACADEMIC OPEN SEPTEMBER 25 SEPTEMBER 2021 HOUSE Choose your own adventure! Welcome to James Madison University! Take some time to look over all the events of the day, and plan out your time here on campus. If you have questions about the day or what JMU Want to take your program virtual? has to offer you, feel free to ask any of our staff and Scan here to download students located all around campus. Have a great day! the Guidebook app. Plan your day, explore campus, get directions and more. English (Harrison 0112) Cultural Communication; Health Communication; Interpersonal College of Arts Foreign Languages, Literatures, STOP Communication; Organizational Communi- & Cultures (Harrison 2113) & Letters 4 cation; Advocacy Studies; Public Relations History (Harrison 0102) School of Media Arts & Design Academic Fair Justice Studies (Harrison 2101) (10 A.M. – 1 P.M.) (Harrison 2105) Crime and Criminology; Global Justice; Interactive Design; Creative Advertising; Located throughout Harrison Hall Social Justice Digital Video & Cinema; Journalism Philosophy/Religion (Harrison 2114) Information Sessions at 11 A.M. & Noon Political Science (Harrison 1261) School of Writing, Rhetoric and Political Science; International Affairs; Technical Communication (Harrison Public Policy and Administration 2246) Information Sessions at 11 A.M. & Noon Technical and Scientific Communication; Writing and Rhetoric School of Communication Studies Information Sessions at 11 A.M. & Noon (Harrison 1241) Conflict Analysis and Intervention; Sociology/Anthropology (Harrison 2102) STOP College Overview Sessions at 10 A.M., 11 A.M., & Noon (Hartman Forum, 2nd Floor) College of 3 College of Business Transfer Advising 10 A.M. – 11:20 A.M. (Hartman 1012) Gillam Center for Entrepreneurship will present at 11 A.M. -

ALTERNATE ROUTES to GRADUATION (Please See Your High School Counselor Before Enrolling in Any Program.)

ALTERNATE ROUTES TO GRADUATION (Please see your high school counselor before enrolling in any program.) Program Name Contact Information Program Details Requirements Renton Technical Intake Navigator There are several ways you can complete high school at RTC: - Age depends on program College Debbie Tully High School Diploma for over 18 – a WA State high school www.rtc.edu/high- [email protected] diploma for people over 18. It takes into account your life and school-completion 206-880-1704 work experience as well as prior credits you may have. GED Preparation – The GED is equivalent to a high school diploma. Classes prepare you for the online tests. It can also be a gateway to your high school diploma. Youth High School Completion (16-20) – a WA State high school diploma for students under 21. Students attend classes at the college or online for credit. Insight School of WA Enrollment & Program Inquiries FREE! Offers a tuition-free, individualized, public high school - Ages 14-20 (can turn 21) Online School 866-800-0017 experience in an online environment. Loaner laptops are - WA state resident available for eligible students. Insight School of Washington is - Completed 8th grade wa.insightschools.net Mickie Foster - Registrar 425-533-2700 x6001 authorized by the Quillayute Valley School District and a K12 - Submit an application [email protected] partner program. - Pre-approval phone call with Enrollment Consultant Job Corps Information FREE! Education and vocational training program that helps - Ages 16-24 1-800-733-5627 young people learn a career and earn a high school diploma. - Meet low-income criteria www.jobcorps.gov Parmis Brazil While enrolled, students receive housing, basic medical needs, - US citizen or legal resident Admissions Counselor living allowance and education. -

Transition to Kindergarten. Early Childhood Research & Policy Briefs, Volume 2, Number 2

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 463 897 PS 030 342 AUTHOR Pianta, Robert; Cox, Martha TITLE Transition to Kindergarten. Early Childhood Research & Policy Briefs, Volume 2, Number 2. INSTITUTION National Center for Early Development & Learning, Chapel Hill, NC. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 8p.; For Volume 2, Number 1, see PS 030 341. CONTRACT R307A60004 AVAILABLE FROM Publications Office, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, CB# 8185, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-8185. Tel: 919-966-0867; e-mail: [email protected]. For full text: http://www.ncedl.org. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO~/PCO~Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Change Strategies; Early Experience; *Educational Policy; Family School Relationship; *Preschool Children; Primary Education; School Readiness; *Student Adjustment; Student Needs; *Transitional Programs IDENTIFIERS *Transitional Activities ABSTRACT The transition to formal schooling is a landmark event for millions of children, but transition practices commonly used may not be well-suited to the needs of children and families. This research and policy brief, a quarterly synthesis of issues addressed by investigators and affiliates of the National Center for Early Development and Learning, focuses on transition activities and policies. The brief examines issues surrounding transition to kindergarten and how U.S. schools support this transition. The brief encourages policy makers to broaden the focus on children's readiness skills to one encompassing the settings that influence those skills--family, peer group, preschool, and school and suggests needed policy changes and factors in need of further research. -

Westwood Preschool Registration Information

WESTWOOD PRESCHOOL REGISTRATION INFORMATION MMO Nursery School 288 Washington Street, Westwood (781) 326-7448 www.mmonurseryschool.com Age: 24 months – 5 years by August 31 Register: For returning students and siblings by lottery January 3rd For alumni families in person January 4 10:00 a.m.-11:30 noon For new families in person rolling admission beginning Saturday Jan. 5 9:00-11:30 th Open House: November 15 7:00-8:30pm *St. John’s Nursery School 95 Deerfield Avenue, Westwood (781) 329-2032 www.stjohnsnursery.org Age: 3 by Sept. 1st and age 4 by Sept. 1st Register: January 8th Open House: November 17th, January 5th 9:30-11:00 Westwood Montessori School 738 High Street, Westwood (781) 329-5557 www.westwoodmontessori.org Age: 2 years 9months- 6 years Register: Ongoing application process for the next school year. Must be 2.9 yrs. by Sept. Call for an application and brochure. Open Houses: October 14th, November 18th 12:00-2:00 Westwood Nursery School 808 High Street, Westwood (781) 326-4659 www.westwoodnurseryschool.org Age: 2.9 – 4.0 years (Preschool) 4.5-5.5 years (Pre-Kindergarten) Register: New students begin registration on January 4th 9:00 a.m. Open House: November 3rd 10:00-12:00, January 4th 9:00-12:00 Westwood Public Schools Integrated Preschool 200 Nahatan Street, Westwood www.westwood.k12.ma.us/preschool 781-326-7500 x-5113 Age: Children must be at least 3 years old and a Westwood resident to enroll. Rolling admissions and ongoing registration with openings. Register: New students register online starting January 15th. -

BG Michaelmas Calendar 2019

Fri 15 08:30 Prep Assembly - Conduct Cup to be awarded 15:15 Girls’ Hockey U11B & U10B v Ratcliffe College (H) 10:00-16:00 ISI Inspectors’ Training Conference at Bilton Grange 15:15 Girls’ Netball 1st v Higham Lane (A) 16:00 Girls’ Netball 2nd v Higham Lane (A) 10:40 Section Meetings 12:15 Reception & Year 1 Exeat begins Thu 5 LAMDA Examinations 12:30 Years 2, 3, Juniors, 3rd & 4th Form Exeat begins 09:30-10:30 The Hobgoblin Theatre Company presents ‘The Wind in 13:00 5th & 6th Form Exeat begins the Willows’ (Reception - Juniors) 13:00 FAB Pre-Prep Movie Afternoon 14:30 Year 1 & Year 2 Christmas Performance 13:40-16:00 Upper School Drama Production Rehearsal 14:30 Girls’ Netball U9A, U9B, U8A & U8B v Crackley Hall (H) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 14:30 Boys’ Rugby U8A, U8B & U8C v Bluecoat (A) E X E A T 18:00 6th Form Parents’ Meeting Sun 17 18:30-19:00 Boarders Return Fri 6 LAMDA Examinations ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Prep Christmas Lunch Mon 18 08:15 Day Children Return Options Programme ends 5th & 6th Form Examinations begin Sat 7 Boarders’ Christmas Weekend 19:30 Parents & Staff Mixed Hockey 14:00 Boys’ Rugby U13A & U12A v Bloxham (H) Headmaster: Mr A Osiatynski Tue 19 18:00 4th Form Parents’ Meeting 14:00 Girls’ Netball Christmas Tournament (H) MA Oxon MEd PGCE FInstLM FRSA Wed 20 14:30 Boys’ Rugby U13A, U13B, U12B & U11A v Spratton Hall (A) 19:00-23:00 FAB Family Christmas Ball 14:30 -

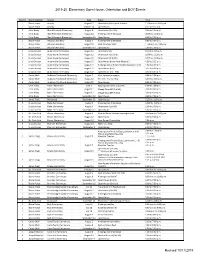

2019-20 Open House Orientation Dates

2019-20 Elementary Open House, Orientation and BOY Events District Board Member School Date Event Time 1 Diane Porter Ackerly August 12 Orientation/Meet your Teacher 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. 1 Diane Porter Ackerly October 16 Open House 8:15 to 9:15 a.m. 7 Chris Brady Alex R Kennedy Elementary August 8 Orientation (1st-5th) 5:00 to 7:00 p.m. 7 Chris Brady Alex R Kennedy Elementary August 10 Kindergarten Orientation 10:00 to 11:30 a.m. 7 Chris Brady Alex R Kennedy Elementary September 10 Open House 6:00 to 7:30 p.m. 1 Diane Porter Atkinson Academy August 7 Kindergarten Orientation 5:30 to 7:00 p.m. 1 Diane Porter Atkinson Academy August 10 Back to School Bash 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 1 Diane Porter Atkinson Academy September 10 Open House 5:30 to 7:00 p.m. 5 Linda Duncan Auburndale Elementary August 12 Orientation (K) 9:00 to 11:30 a.m. 5 Linda Duncan Auburndale Elementary August 12 Orientation (1st-2nd) 10:00 to 11:30 a.m. 5 Linda Duncan Auburndale Elementary August 12 Orientation (3rd-5th) 10:45 to 11:30 a.m. 5 Linda Duncan Auburndale Elementary August 27 Open House (K and New Student ) 4:30 to 5:15 p.m. 5 Linda Duncan Auburndale Elementary August 27 Kindergarten and New Student Classroom Visit 4:30 to 6:30 p.m. 5 Linda Duncan Auburndale Elementary August 27 Open House (ESL) 5:15 to 6:00 p.m. -

Rochester Institute of Technology Fall 2016 Dear Open House Registrant

. R I T Rochester Institute of Technology Office of Undergraduate Admissions Rochester Institute of Technology Bausch & Lomb Center 60 Lomb Memorial Drive Rochester, New York 14623-5604 Phone: (585) 475-6631 E-mail: [email protected] www.admissions.rit.edu Fall 2016 Dear Open House Registrant: We have received your reservation for our Fall Open House on Saturday, November 12th and we are looking forward to your visit. Thank you for using our electronic confirmation. Enclosed you will find a visitor parking permit, campus map, and directions to RIT. When you arrive on campus, please follow the signs to parking lot D or G. Please display your parking permit on the dashboard of your vehicle. Once you park your vehicle, please follow the signs leading to the Gordon Field House (GOR). Our staff and students will be available to greet you and help you plan your day. Also included is a tentative schedule that outlines the activities we have planned for Open House. A continental breakfast will be available during morning check-in. If you would like to have lunch in our student cafeteria, Gracie's, you are welcome to do so. Lunch passes can be purchased for $9.00 per person during check-in. Students who are interested in applying to the School of Art, School of Design, or School for American Crafts may have their portfolios reviewed or critiqued from 12:30-2:00 p.m. Please note that students interested in our School of Photographic Arts & Sciences or School of Film & Animation are not required to submit a portfolio. -

Curriculum Vitae of Vickie Eileen Lake

1 CURRICULUM VITAE VICKIE EILEEN LAKE The University of Oklahoma – Jeannine Rainbolt College of Education Schusterman Center 4502 E. 41st Street Phone: 918.660.3984 Tulsa, OK 74135-2553 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION 1999 Doctor of Philosophy, The University of Texas at Austin. Major: Curriculum and Instruction. Specialization: Early Childhood Education. Major Professor: Dr. Lisa S. Goldstein 1989 Master of Education, George Peabody College for Teachers at Vanderbilt University. Major: Elementary Education. Major Professor: Dr. Carolyn Evertson 1987 Bachelor of Science, Texas Tech University. Major: Human Development and Family Studies. Specialization: Teachers of Young Children. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2016-PRESENT Associate Dean, Jeannine Rainbolt College of Education at the University of Oklahoma – Tulsa • Serve as the key liaison for the college to the JRCoE-Tulsa program coordinators and the OU-Tulsa administration • Work closely with the graduate deans in Tulsa and Norman • Develop and implement a strategic plan for JRCoE-Tulsa, focusing on: recruiting and enrollment management, student experience and building community, research development, & space needs assessment and planning • Work with JRCoE staff to administer JRCoE-Tulsa budget, including the pool for overload/adjunct/summer teaching • Administer and approve the Tulsa class schedule • Supervise Tulsa staff • Serve as ex-officio Tulsa Academic Affairs Research Committee 2016-PRESENT Full Professor, Department of Instructional Leadership & Academic Curriculum, -

Boarding Houses Information Handbook

Boarding Houses Information Handbook Boarding House Handbook | 1 The information in this Booklet is correct as at April 2020. The School reserves the right to make changes where deemed necessary. 00 School Aims 01 Welcome to JIS Boarding 02 Boarding Ethos & Practice 04 Osprey House 06 Eagle House 08 Kingfisher House 10 Ibis House 12 Myna House 13 Weekend Enrichment 14 School Week Routines 15 Meals 15 Medical Issues and Matrons 16 Boarding Events 17 What to bring to boarding 18 What not to bring to boarding 19 A – Z of Boarding at JIS 22 Boarding House Map THE SCHOOL AIMS AIM What to do? Awarded for... Be curious • Acquiring new skills. • Showing respect for our peers. Be responsible ENGAGEMENT • Actively taking charge of our own Be a lifelong learner learning. Be optimistic • Showing perseverance. • Keeping things in perspective. Be self aware RESILIENCE • Making time to have fun, relax and Be determined stay fit. Be collaborative • Expressing ideas creatively. • Actively listening. Be a good listener COMMUNICATION • Working harmoniously with those Be compassionate around us. • Working together in a spirit of Be respectful unity and companion. INTEGRATION Be inclusive • Understanding others. Be kind • Valuing individual contributions but sharing responsibilities. • Being creative and imaginative. Be creative • Applying what we learn in the THINKING Be a problem solver classroom in the outside world. Be reflective • Reflecting upon our experiences to make better choices in the future. Be inspirational • Showing enthusiasm, optimism and warmth to others. Be humble LEADERSHIP • Showing humility. Be authentic • Being authentic. Welcome to JIS Boarding The Boarding Houses are situated within the extensive and completely private, 120 acre JIS campus. -

Open House for Middle School Students & Families

Open House for Middle School Students & Families Bourne High School Objective: Parents will have an understanding of Bourne High School’s: . Mission, Expectations and 21st Century Learning Skills . Academic levels . Academic and Career Pathways . Sequencing of core courses . Course selection process . Elective options available . Extra-curricular opportunities . Additional educational opportunities You will also have an opportunity to tour the elective areas and meet current students! Our Mission & Core Values and Beliefs MISSION STATEMENT . Bourne High School’s Mission is to provide a safe and academically rigorous learning community that fosters both personal and social growth for all. We provide a diverse academic program that prepares students for post – secondary education, the 21st Century global workforce, and responsible citizenship. CORE VALUES AND BELIEFS . Academic rigor and challenge for all students . Foundation of literacy for all learners . Cooperation and team work . Responsibility for one’s actions . Recognition and respect of individual differences and points of view . School culture that fosters a positive and safe environment for all 21ST CENTURY LEARNING EXPECTATIONS . Read, write and communicate effectively and clearly . Think critically and problem solve independently and collaboratively . Set personal, wellness, academic, and occupational goals . Engage in creative, expressive, and innovative learning . Demonstrate personal responsibility and cultural awareness Your Guidance Counselor & Support Services – Valuable High School Resources . Counselors work with the same students all four years . Serve as liaisons among students, parents, and teachers . Register students for Naviance, our college and career exploration program – a 4 year resource/tool for students Student Last Name: Guidance Counselor: Email [email protected] Mrs. Kim Iannucci D - M [email protected] Mr. -

College Open House and Tour Events (Alphabetical by College) Updated 3/1/2018

College Open House and Tour Events (Alphabetical by college) Updated 3/1/2018 The University of Alabama - Tuscaloosa, AL University Days University Days offer prospective students information on topics such as admissions, majors and minors, academic support and programs, costs, financial aid and scholarships, and on-campus living and dining. Please join us and a group of outstanding high school and transfer students like yourself for a daylong visit at The University of Alabama. Spring 2018 – Special Reception Wednesday, March 7, 2018 at 7:00 pm Thornblade Country Club 1275 Thornblade Blvd Greer, SC 29650 Register at: gobama.ua.edu/greenville-area-reception Allen University - Columbia, SC Allen University offers guided tours Monday through Friday, from 9:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. and 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm. Tours provide students and their parents the opportunity to learn more about Allen University. Please RSVP by calling the Office of Admissions 1(877)625-5368 or by E-mailing: [email protected] See more at: http://www.allenuniversity.edu/visiting-allen/ Anderson University - Anderson, SC At the Trojan Preview event you will experience AU’s exceptional academics, dynamic student life, and picturesque campus. October 27, 2017 January 16, 2018 (MLK Day) All Access/Overnight dates: November 16-17, 2017 & January 25-26, 2018 First Glance at AU: 1 September 22, 2017 March 23, 2018 April 6, 2018 October 20, 2017 March 29, 2018 April 13, 2018 November 10, 2017 April 2, 2018 April 20, 2018 February 19, 2018 April 4, 2018 For more information: https://www.andersonuniversity.edu/visit/campus-visit Armstrong State University - Savannah, GA Pirate Preview Open House: October 28, 2017 February 17, 2018 Meet professors, talk with students, tour campus, see first-year housing, learn about financial aid, and participate in specially designed sessions.