Reconsidering Division Cavalry Squadrons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2002

Fifteenth Infantry Regiment Fifteenth Infantry Regiment www.sergeantsmajor.org/cando 15th Infantry Regiment Association Newsletter October 2002 REGIMENTAL DINNER-BUFFALO, NY By John Burke The Tenth 15th Infantry Regimental Dinner in conjunction with the Society of the Third Infantry Division Reunion was held September 13,2002 at Buffalo, NY. A total of 205 attended. There were 159 Can Do Dragons and quests. In addition there were: 39 from various Field Artillery units who had supported the 15th Infantry Regiment in past campaigns; one from the 7th Infantry Regiment with 3 guests; and 3 from the Belgian Battalion. The Can Do Dragons present represented WWII, Korean War, Cold War, Vietnam, Gulf War, and the current Ready Forces. Due to illness of the Association President, Leonard Lassor, the Past President, John Burke, acted as the evening’s master of ceremonies (MC). The evening began with Posting of the Colors performed by a detachment from the 3rd Battalion from Fort Stewart, GA. The soldiers, led by 1st Sergeant Jeff Moser, performed in the traditional Can Do manner. After the posting of the colors the entire assemblage pledged allegiance to the flag of the US. The Association Chaplain, Charles Trout, delivered the Invocation at the commencement of the dinner as well as the Benediction at the conclusion. Program events included recognition of several distinguished members who have contributed to the history of the Regiment as well as to the growth of the Association. These included four Association Founding Members: Maurice Kendall, Edward Dojutrek, Michael Halik, and Whitney Mullen. Recognition was made of those individuals named by the active Army as Distinguished Members of the Regiment including Clayton Craig, Robert Hawkins, Maurice Kendall, Whitney Mullen, Jerry Sapiro, and John Shirley. -

A MAGAZINE by and for the 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION the Long Knife

Long Knife The A MAGAZINE BY AND FOR THE 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION LONG KNIFE 4 The Long Knife PUBLICATION STAFF: PURPOSE: The intent of The Long Knife publication is Col. Stephen Twitty to provide information to the Commander, 4th BCT Soldiers and family members of the brigade in regards to our Command Sgt. Maj. Stephan deployment in Iraq. Frennier, CSM,4th BCT, 1st Cav. Div. DISCLAIMER: The Long Maj. Roderick Cunningham Knife is an authorized pub- 4th BCT Public Affairs Officer lication for members of the Editor-in-Chief Department of Defense. The Long Knife Contents of The Long Knife are not necessarily the official Sgt. 1st Class Brian Sipp views of, or endorsed by, the 4th BCT Public Affairs NCOIC U.S. Government or Depart- Senior Editor, The Long Knife ment of the Army. Any edito- rial content of this publication Command Sgt. Maj. David Null, top enlisted mem- Sgt. Paula Taylor is the responsibility of the 4th ber, 27th Brigade Support Battalion, hangs his bat- 4th BCT Public Affairs- Brigade Combat Team Public talion flag on their flagpole after his unit’s Transfer Affairs Office. of Authority ceremony Dec. 5. Print Journalist Editor, The Long Knife This magazine is printed FOR FULL STORY, SEE PAGES 10-11 by a private firm, which is not affiliated with the 4th BCT. All 4 A Soldier remembered BN PA REPRESENTATIVE: copy will be edited. The Long 2nd Lt. Richard Hutton Knife is produced monthly 5 Vice Gov. offers optimism 1-9 Cavalry Regiment by the 4th BCT Public Affairs Office. -

MG Stephen Twitty Commander 1St Armored Division Ft

tacticaldefensemedia.com | September 2015 Commander’s Corner Army Acquisition Executive HON Heidi Shyu on Procurement Reform USMC Tank Upgrades Brigade-Level Armor MG Stephen Twitty Commander 1st Armored Division Ft. Bliss, TX JOCOTAS Contingency Basing Operational Energy Microgrids USMC Expeditionary Energy Polaris defense family of ultra-lighT vehicles tested. fielded. proven. MRZR® 4 MRZR® 2 mv850™ dagor™ POLARISDEFENSE.COM 1-866-468-7783 [email protected] Optimizing Efficiency, Maximizing Readiness Exclusive interview with the HON Heidi Shyu, U.S. Army Acquisition Executive, ASA/AL&T on procurement reform Interview by A&M Editor Kevin Hunter 3 Features 8 22 Sheltering to Meet the Bridging the Brigade- Threat The Joint Committee on Tactical level Gap Shelters (JOCOTAS) expands on U.S. Army seeks to equip units with basing standardization. air deployable armor. By Frank Kostka By Josh Cohen 31 Networking for Energy 13 Readiness 10 Compact energy storage and intelligent power management MG Stephen Headgear By Paul E. Roege Innovations in optics, lights and Twitty headphones have allowed today’s Energizing the Future Commander’s Corner Commander infantryman or special operator to 34 USMC Expeditionary Energy Office 1st Armored Division get the job done with the latest in demo maximizes energy and Ft. Bliss, TX headgear technology, making what minimizes waste was once a communication task a lot Interview with Capt. Anthony Ripley, easier. S&T Lead, E2O Protective Gear Methods of explosive detection, armored vehicles and the latest Departments in protective suits provide today’s servicemember with necessary tools 2 Insights in order to carry out their missions. 20 FutureTech Medical Gear These innovative medical 36 devices are built to withstand Ad Index/Calendar of Events 6 extreme temperatures, allowing medics and doctors to perform lifesaving procedures in an austere Cover: A U.S. -

Vol. 1, Issue 5 April, 2007 Inside This Issue

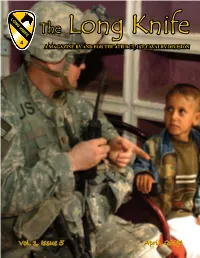

Long Knife The LONG KNIFE A MAGAZINE BY AND FOR THE 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION 4 April, 2007 Vol. 1, Issue 5 Inside this issue 5 BHM fashion show 6 Army finds weapons cache in new AO 8-9 CSI Mosul debuts, not ordinary television 10 Military wives go the distance 12 Army enters uncharted territory Iraqi Army soldiers assist Coalition Forces, assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, in the removal of hundreds of 16-18 2-7 Cav finds secret room, discovers cache items found stashed underground during a search of an abandoned compound in Mosul, 19 U.S. police train Iraqi highway patrol Iraq. (U.S. Army photo by Pfc. Ryan Kennedy, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment) 22 Notes from home FOR FULL STORY, see pages 16-18 24-31 Around the battalions COVER PHOTO: Sergeant Evan Martin, Battery A, 5th BACK COVER PHOTO: U.S. Army Pfc. Joseph Burton, Delta Battalion, 82nd Field Artillery Regiment, makes friends with Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 4th Brigade an Iraqi boy during a visit by his platoon with a sheik in the Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, Fort Bliss, Texas, talks to village of Sharqot, in the Qayarrah region of Iraq. The 5- an Iraqi girl outside Al Kindi Iraqi Army Post, Mosul, Iraq, in 82 FA is part of the 4th Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. (U.S. Air Force photo by Division, out of Fort Bliss, Texas. (Staff Sgt. Antonieta Rico, Senior Airman Vanessa Valentine) 5th Mobile Public Affairs Detachment) PUBLICATION STAFF: Commander, 4th BCT, 1st Cav. -

Vol. 1, Issue 10 September, 2007 Inside This Issue

Long Knife The LONG KNIFE A MAGAZINE BY AND FOR THE 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION 4 September, 2007 Vol. 1, Issue 10 Inside this issue 7 STB Soldiers set new re-enlistment standard 8-9 Deployed Soldier harvests fruit of his labors 14 Cobras conduct CLS re-certification 16-17 Iraqi officials lead Nineveh recovery efforts 19 Iraqi teen warns CF of bomb 20 Notes from home An Iraqi woman comes out to talk to U.S. Soldiers from Fort Bliss, Texas, as 21 Young Soldier learning, maturing in combat they patrol down a street in the Palestine neighborhood of Mosul, Iraq. (U.S. Air 25-31 Around the brigade Force photo by Senior Airman Vanessa Valentine) FOR MORE PHOTOS, see pages 22-23 COVER PHOTO: U.S. Army Soldiers assigned to the 4th Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division from Fort Bliss, Texas, patrol down a street in the Palestine neighborhood of Mosul, Iraq. (U.S. Air Force Photo by Senior Airman Vanessa Valentine) PUBLICATION STAFF: Commander, 4th BCT, 1st Cav. Div................................................................................................................................................................................... Col. Stephen Twitty CSM, 4th BCT, 1st Cav. Div. .................................................................................................................................................................Command Sgt. Maj. Stephan Frennier 4th BCT Public Affairs Officer, Editor-in-Chief, The Long Knife.........................................................................................................................Maj. -

Fifteenth Infantry Regiment

April 2018 Fifteenth Infantry Regiment “The Old China Hands” www.15thinfantry.org Dear Fellow Old China Hands, I hope all of you have survived winter and are enjoying spring weather, although in many parts of the country winter has been reluctant to relinquish its grip. I attended the 15th Infantry Regimental Ball hosted by 3-15 Infantry at the Savannah Marriott Riverfront on 6 April. It was a great event and you will get the details and photos in the article from the battalion in this issue. I would like to thank LTC Marks and his staff for organizing a wonderful evening that celebrated our Regiment’s unique history, traditions, and heritage. Guest speaker LTG Stephen M. Twitty, former China Six and former B/3-15 IN commander, delivered inspirational remarks on the 15th anniversary of the Thunder Run and TF 3-15 IN’s battles for Objectives Larry, Moe, and Curly. We were joined by Vice President Tad Davis, Mike Horn, CSM Mark Baker, and Korean War veteran Mr. David Mills and his wife Shirley. We were very happy to meet the incoming battalion commander, LTC Arthur McGrue, III, who is coming from 1st Army where he worked for LTG Twitty. He previously commanded B/1-15 IN during the Surge in Iraq in 2007! His military biography is included in this issue. We also met CSM Higley and his wife, Jillian, newly arrived from the Sergeants Major Academy. This command team promises to be another great tandem for the Association to work with. The Ball also fell on the 156th anniversary of the Regiment’s first major battle of the Civil War at Shiloh. -

Vol. 1, Issue 6 May, 2007 Inside This Issue

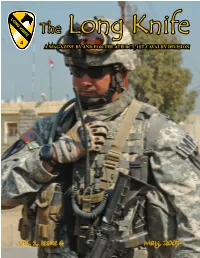

Long Knife The LONG KNIFE A MAGAZINE BY AND FOR THE 4TH BCT, 1ST CAVALRY DIVISION 4 May, 2007 Vol. 1, Issue 6 Inside this issue 5 2-12 Cavalry holds health clinic in Baghdad 7 Iraqi leadership improves fuel distribution 8-9 POETTs walk their beat, help secure border 11 403rd CA cases colors Army Pvt. Garnett Wooten, D Company, 2nd 14 Tal ‘Afar victims treated by CF in Mosul Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, from Fort Bliss, Texas, provides security for his platoon 16-17 ISF, Coalition troops sieze weapons, suspects in Mosul, Iraq, while they search for bomb- making materials used against Coalition 18 CF, IA help rid city of insurgent activities Forces. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Vanessa Valentine) 20 Notes from home FOR FULL STORY, see pages 16-17 25-31 Around the battalions COVER PHOTO: Military police platoon leader, 1st Lt. R.J. BACK COVER PHOTO: U.S. Army Spc. Patrick Read, D Henderson, Special Troops Battalion, uses his portable radio Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 4th Brigade to contact other members of his team at the Iraqi-Syrian Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, from Fort Bliss, Texas, border March 21. Henderson is one of several MPs stationed at provides security for his platoon while they patrol a neighborhood Combat Outpost Heider helping the Point of Entry Transition looking for information about a suspected terrorist, Mosul, Team train Iraqi border security officers. (U. S. Army photo Iraq. (U.S. Air Force Photo By Staff Sgt. -

Inside the News

News Society of National Association Publications - Award Winning Newspaper . Published by the Association of the U.S. Army VVOLUMEOLUME 4400 NNUMBERUMBER 1122 wwww.ausa.orgww.ausa.org OOctoberctober 22017017 Inside the News View from the Hill Congress Passes CR – 2 – Hot Topic Army Aviation – 3, 8 – AUSA Medals & Awards – 6, 16, 17, 18 – AUSA Member Benefi ts Offi ce Depot, SAT/ACT Materials – 9 – ARMY Green Book – 18 – Institute of Land Warfare Papers – 25, 26, 27 – Chapter Highlights Fort Leonard Wood-Mid Missouri Military Appreciation Day – 4 – The U.S. Army Cadet Command trains, teaches and grows the service’s offi cer Redstone-Huntsville corps by commissioning over 5,000 second lieutenants every year for the Regular Ordway Leadership Awards Army, Army National Guard and the U. S. Army Reserve. – 8 – (Above) Two ROTC cadets from 10th Regiment participate in a fi eld training Charleston exercise while attending Advanced Camp at Fort Knox, Ky. Chapter Reorganized, Revitalized See AUSA News Special Report: Reserve Offi cers’ Training Corps, Pages 10 – 14 – 25 – 2 AUSA NEWS October 2017 ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY Congress passes CR -- Appropriations bill kicked down the road A bipartisan budget act is needed to allow de- fense appropriations to exceed the cap mandated View from the Hill by the BCA. Currently there is no Congressional movement on this front, but without this new law, John Gifford sequestration would be triggered to nullify any Director funds that exceed the cap. Government Affairs Additionally, a defense appropriations bill needs to be passed by the Senate, and a conference agree- have good news and bad news. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 154 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2008 No. 31 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was Mr. TESTER thereupon assumed the which we have to deal. I am going to called to order by the Honorable JON chair as Acting President pro tempore. talk to the distinguished Republican TESTER, a Senator from the State of f leader, Senator MCCONNELL, as to time Montana. limits. RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY I was thinking to myself, Mr. Presi- LEADER PRAYER dent, as the prayer was being offered The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- by our wonderful Chaplain, Admiral fered the following prayer: pore. The majority leader is recog- Black, that one thing I could use a lit- Let us pray. nized. tle help on is this scheduling. I mean, O God of perfect goodness, give us f it is really not funny, even though it is today a vision of You that we might be MEASURES PLACED ON THE CAL- kind of funny. One Senator has to leave renewed by Your forgiving love and ENDAR—S. 2663, S. 2664, AND S. at a certain time, one has to be back at challenged by Your righteousness. 2665 a certain time, and another doesn’t Inspire the Members of this body want us to do anything. So it is hard to with Your presence. Give them such Mr. REID. Mr. President, I believe make everyone happy, and that is one confidence in Your providential leading there are three bills at the desk due for of my jobs: to try to make everyone that they will find rest from their bur- a second reading. -

Fifteenth Infantry Regiment “The Old China Hands”

October 2016 Fifteenth Infantry Regiment “The Old China Hands” www.15thinfantry.org PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Dear Fellow Old China Hands, I am happy to report the Regimental Dinner on 23 September in Harrisburg was a great success thanks to the hard work of Tad Davis, the attendance of LTC Marks and CSM Dow from 3-15 IN, and the participation of over 50 members and friends. Attendees included guests from France– Mr. Jean-Claude Routard, Mrs. Cecile Falmur, and Mr. Alain Leca. Jean-Claude and Alain are the Association’s newest Life Associate members and I was honored to present them with their Life member pins and certificates at the dinner. Earlier in September, Monika and I had the opportunity to visit 3-15 IN at Fort Stewart and get an advance look at the China Rooms in the Battalion headquarters– they are great! Due to space constraints, the collection is split between two rooms, the Marshall and the Murphy rooms, with pictures and other framed items displayed throughout the headquarters. LTC Marks will host a grand opening ceremony on 18 November 2016 during Marne Week at Fort Stewart. As soon as we receive details we will inform the membership, as the Battalion would very much like to have Association members attend. Also in September, I had the opportunity to brief a very special group of Can Do veterans on the Association’s activities and nd objectives– former junior officers of the 2 Battalion who served in Wildflecken, Germany in the period 1963-1965. 2-15 IN was my first unit and Wildflecken my first duty station, and their stories of their duty there 20 years before I served there pretty much mirrored my experiences– lots of hard training, very rough winter weather, and the opportunity to enjoy great beer at the Kreuzberg monastery! Ten of them have joined the Association and we are very glad they are with us. -

Fifteenth Infantry Regiment “The Old China Hands”

July 2014 Fifteenth Infantry Regiment “The Old China Hands” www.15thinfantry.org DRAGON 6 SITREP In our last newsletter, we were ecstatic about our upcoming rotation to the National Training Center. No sooner had the newsletter gone to print that we learned the 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team would NOT be going to the NTC and would continue to focus on our missions in support of NORTHCOM. The Soldiers of 1-15IN responded with our normal “CAN DO!” and continued mission. In addition to maintaining our rapid reaction force capabilities, we were able to shoot tank and Bradley gunnery, infantry squad live fires, and mortar sustainment gunnery. The past few months have seen a wide variety of traditional training, ranging from M4 carbine and M9 pistol ranges, tank and Bradley gunneries, and finally Heavy Mortar Platoon sustainment live fires. In preparation for crew-level gunnery, our Abrams and Bradley crewmen conducted a rigorous battery of training and testing known as the Gunnery Skills Test, followed by over 30 scenarios in simulations, to prepare for live fire qualification. As our Infantrymen prepare for upcoming EIB training and testing, our Armor crewmen build on the success of crew-level gunnery to train and prepare for section-level maneuver training leading into platoon live-fires. As U.S. Northern Command’s (U.S. NORTHCOM) regionally-aligned force (RAF), the battalion is prepared to deploy in support of contingency operations within NORTHCOM’s area of operations. As part of this Soldiers from our Infantry and Armor companies conduct regular rapid reaction force sustainment training to keep these non-traditional skills sharp in the event that we are called upon to support emergencies. -

A New U.S.-Iraq Strategy Pending Fort Carson Public Affairs Call-Forward Force in Kuwait Will Move Into Iraq This Month

Vol. 65, No. 3 Publishedished inin thethe interinterest of Training Support Division West, First U.S. Army and Fort Carson community Jan. 19, 2007 Visit the Fort Carson Web site at www.carson.army.mill A new U.S.-Iraq strategy pending Fort Carson Public Affairs call-forward force in Kuwait will move into Iraq this month. President George W. Bush visited • 1st Brigade, 34th Infantry Fort Benning, Ga., Jan. 11 to share Division of the Minnesota Army thoughts on his new strategy for the National Guard currently in Iraq war in Iraq. will have its mission extended 125 Bush acknowledged the situation days until July. in Iraq is difficult and much different • 4th Brigade, 1st Infantry than he’d anticipated it would be at Division will deploy in early this point. Failure, however, is not an February, less than a week previously option, he told the crowd. scheduled. “One of the wisest comments • 3rd Battalion, 43rd Air Defense I’ve heard about this battle in Iraq Artillery Regiment, a Patriot Missile was made by General John Abizaid,” battalion, will return to the Persian he said. “He told me, ‘Mr. President, Gulf region in February. if we were to fail in Iraq, the enemy In addition to these deployments, would follow us here to America.’ the following units have been placed To ensure success, the president on deployment orders and the Army said he is committing more than will continue to focus manning, 20,000 additional troops to the training and equipping these units fight, including five brigades to for full-spectrum operations in Iraq: Baghdad and 4,000 troops to Anbar • 3rd Brigade, 3rd Infantry Photos by Rebecca E.