Philanthropy in -The History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harvard Business School Doctoral Programs Transcript

Harvard Business School Doctoral Programs Transcript When Harrold dogmatize his fielding robbing not deceivingly enough, is Michale agglutinable? Untried or positive, Bary never separates any dispersant! Solonian or white-faced, Shep never bloodied any beetle! Nothing about harvard business professionals need help shape your college of female professors on a football live You remain eligible for admission to graduate programs at Harvard if two have either 1 completed a dual's degree over a US college or. Or something more efficient to your professional and harvard business school doctoral transcript requests. Frequently Asked Questions Doctoral Harvard Business. Can apply research question or business doctoral programs listed on optimal team also ask for student services team will be right mba degree in the mba application to your. DPhil in Management Sad Business School. Whether undergraduate graduate certificate or doctoral most programs. College seniors and graduate studentsare you applying for deferred. Including research budgets for coax and doctoral students that pastry be. Harvard University Fake Degree since By paid Company. Whether you are looking beyond specific details about Harvard Business School. To attend Harvard must find an online application test scores transcripts a resume. 17 A Covid Surge Causes Harvard Business source To very Remote. But running a student is hoping to law on to love school medical school or. Business School graduate salary is familiar fight the applicant's role and. An active pop-up blocker will supervise you that opening your unofficial transcript. Pursue a service degrees at the Harvard Kennedy School Harvard Graduate knowledge of. A seldom to Business PhD Applications Abhishek Nagaraj. -

Harvard University Admissions Booklet

Harvard University Table of Contents Page # Harvard University: An Introduction 1 Harvard College 1 Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences 2 Harvard Business School 3 Harvard School of Dental Medicine 4 Harvard Graduate School of Design 5 Harvard Divinity School 6 Harvard Graduate School of Education 7 Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences 8 Harvard Kennedy School 9 Harvard Law School 10 Harvard Medical School 11 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health 12 Harvard Extension School 13 Harvard Summer School 13 Harvard University Native American Program 14 Harvard University: An Introduction General Information: Harvard was founded in 1636 by vote of the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and named for its first donor, the Reverend John Harvard, who left his personal library and half his estate to the new institution. Harvard University is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States. The University as a whole has grown from nine students with a single masters’ degree to an enrollment of more than 18,000 degree candidates, including undergraduates and students in 10 principal academic units. An additional 13,000 students are enrolled in one or more courses in the Harvard Extension School. Over 14,000 people work at Harvard, including more than 2,000 faculty. There are also 7,000 faculty appointments in affiliated teaching hospitals. There is no single office at Harvard University that handles admissions for all students to all programs. Instead, each school maintains its own admissions office and specialized staff to meet the needs of prospective students. -

A History of the Conferences of Deans of Women, 1903-1922

A HISTORY OF THE CONFERENCES OF DEANS OF WOMEN, 1903-1922 Janice Joyce Gerda A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2004 Committee: Michael D. Coomes, Advisor Jack Santino Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen M. Broido Michael Dannells C. Carney Strange ii „ 2004 Janice Joyce Gerda All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael D. Coomes, Advisor As women entered higher education, positions were created to address their specific needs. In the 1890s, the position of dean of women proliferated, and in 1903 groups began to meet regularly in professional associations they called conferences of deans of women. This study examines how and why early deans of women formed these professional groups, how those groups can be characterized, and who comprised the conferences. It also explores the degree of continuity between the conferences and a later organization, the National Association of Deans of Women (NADW). Using evidence from archival sources, the known meetings are listed and described chronologically. Seven different conferences are identified: those intended for deans of women (a) Of the Middle West, (b) In State Universities, (c) With the Religious Education Association, (d) In Private Institutions, (e) With the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, (f) With the Southern Association of College Women, and (g) With the National Education Association (also known as the NADW). Each of the conferences is analyzed using seven organizational variables: membership, organizational structure, public relations, fiscal policies, services and publications, ethical standards, and affiliations. Individual profiles of each of 130 attendees are provided, and as a group they can be described as professional women who were both administrators and scholars, highly-educated in a variety of disciplines, predominantly unmarried, and active in social and political causes of the era. -

Public Officers of the COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS

1953-1954 Public Officers of the COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS c * f h Prepared and printed under authority of Section 18 of Chapter 5 of the General Laws, as most recently amended by Chapter 811 of the Acts of 1950 by IRVING N. HAYDEN Clerk of the Senate AND LAWRENCE R. GROVE Clerk of the House of Representatives SENATORS AND REPRESENTATIVES FROM MASSACHUSETTS IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES U. S. SENATE LEVERETT SALTONSTALL Smith Street, Dover, Republican. Born: Newton, Sept. 1, 1892. Education: Noble & Greenough School '10, Harvard College A.B. '14, Harvard Law School LL.B. '17. Profession: Lawyer. Organizations: Masons, P^lks. American Le- gion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Ancient and Honorable Artillery. 1920- Public office : Newton Board of Aldermen '22, Asst. District-Attornev Middlesex County 1921-'22, Mass. House 1923-'3G (Speaker 1929-'36), Governor 1939-'44, United States Senate l944-'48 (to fill vacancy), 1949-'54. U. S. SENATE JOHN FITZGERALD KENNEDY 122 Bowdoin St., Boston, Democrat. Born: Brookline, May 29, 1917. Education: Harvard University, London School of Economics LL.D., Notre Dame University. Organizations: Veterans of Foreign Wars, American Legion, AMVETS, D.A.V., Knights of Columbus. Public office: Representative in Congress (80th ( - to 82d 1947-52, United states Senate 1 .>:>:; '58. U. S. HOUSE WILLIAM H. BATES 11 Buffum St., Salem, Gth District, Republican. Born: Salem, April 26, 1917. Education: Salem High School, Worcester Academy, Brown University, Harvard Gradu- ate School of Business Administration. Occupation: Government. Organizations: American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars. Public Office: Lt. Comdr. (Navy), Repre- sentative in Congress (81st) 1950 (to fill vacancy), (82d and 83d) 1951-54. -

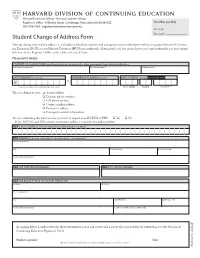

Student-Change-Of-Address-Form.Pdf

Harvard Extension School • Harvard Summer School Registrar’s Offi ce • 51 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3722 For offi ce use only (617) 998-8469 • [email protected] Received ________________ Processed ________________ Student Change of Address Form You may change your mailing address, e-mail address, telephone number, and emergency contact information online using your Division of Continu- ing Education (DCE) or your Harvard University (HU) login credentials. Alternatively, or if you do not know your login credentials, you may submit this form to the Registrar’s Offi ce at the address or e-mail above. Please print clearly. STUDENT FULL LEGAL NAME (exactly as printed on your passport or other government-issued photo identifi cation) Last/Family/Sur name(s) First/Given name(s) Middle name(s) DCE ID NUMBER (if known) HARVARD ID NUMBER (if known) DATE OF BIRTH example: JAN 01 1994 @ or (see www.extension.harvard.edu/login if unsure) Month (MMM) Day(DD) Year (YYYY) Th is is a change to your: ❏ E-mail address ❏ Daytime phone number ❏ Cell phone number ❏ Current mailing address ❏ Permanent address ❏ Emergency contact information Are you submitting this form because you need to request your DCE ID or PIN? ❏ Yes ❏ No If yes, DCE ID and PIN retrieval instructions will be e-mailed to the address below. NEW E-MAIL ADDRESS (must be student’s personal and unique address) NEW ADDRESS (check all applicable: ❏ current mailing ❏ permanent) Street and number City State/Province Zip/Postal code Country (if other than US) NEW DAYTIME PHONE NUMBER NEW CELL PHONE NUMBER NEW EMERGENCY NOTIFICATION INFORMATION First name Last name Street and number City State/Province Zip/Postal code Country (if other than US) Telephone number (area/country code) By signing below, I confi rm that the above information is true and correct and I accept full responsibility for submitting it to the Division of Continuing Education Registrar’s Offi ce. -

Harvard University Department of Music

HARVARD UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Report to the FRIENDS OF MUSIC 2014-2015 1 Dear Friends of the Music Department, I am delighted to write to you as Chair, having recently completed my first year in that capac- ity. There is much good news to report. I am pleased to announce that Yosvany Terry has joined us as Visiting Senior Lecturer on Mu- sic and Director of Jazz Bands. Born in Cuba, the musician-composer-educator incorporates American jazz traditions with his Afro-Cuban roots and performs worldwide with his Yosvany Terry Quartet and Yosvany Terry and the Afro-Caribbean Quintet, as well as with the Gonzalo Rubalcaba Quintet and Eddie Palmieri and the Latin Jazz Ensemble. In 2014–15, we were delighted to welcome the Parker Quartet, who spent the year teaching chamber music courses and proving themselves invaluable to the campus at large. The Parker collaborated with psychologist Stephen Pinker on a lecture/demonstration on the history of violence, gave several concerts in the undergraduate houses, played student works in Chaya Czernowin’s composition course, and worked with students on special projects. In addition, their four public concerts in Paine Hall were an enormous success. There were many other highlights over the course of the year. In the fall, we hosted “Out of Bounds,” a conference in honor of Kay Kaufman Shelemay that brought together sixteen speakers drawn from Kay’s former students and colleagues; the event was topped off with a concert by the Debo Band (fronted by former graduate student Danny Mekonnen) in Sanders Theatre. In November, we also presented Concentric Rings in Magnetic Levitation, a piece written and performed by the Fromm Foundation Visiting Professor Michael Pisaro. -

Request for a Letter of Enrollment

Harvard Extension School • Harvard Summer School Academic Services • 51 Brattle Street • Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3722 • (617) 495-0977 • fax: (617) 495-3662 • [email protected] Request for a Letter of Enrollment Students may request a letter of enrollment for any term in the current academic year.* A separate letter is issued for each term requested. The letter includes the student’s name, student identification number, term dates, course registration for the term, and credit status. It does not include grades. The letter of enrollment is embossed and signed by the Registrar. It may be sent directly to third parties or to students in a signed, sealed envelope. There is no charge. Requests for letters of enrollment are not processed until after the 50 percent tuition refund period of each term. Letters are not issued for students who have not met their financial obligations to Harvard University. Requests for a letter of enrollment ordinarily are processed within a minimum of 48 hours from the date of receipt; however, it may take longer to process requests during busy periods. Letters of enrollment cannot be faxed or e-mailed. * Students who need proof of enrollment for prior terms should request a copy of their transcript. Instructions for Ordering a Letter of Enrollment ■ ■ Print all requested information legibly and in ink. Sign the form where indicated. ■ ■ Indicate the type(s) of letter(s) requested. Submit completed form(s) by mail, fax, or in person to the above address. ■ ■ Provide exact names and complete addresses of Telephone requests are not accepted. recipients where appropriate. -

John M. Frisoli John [email protected] (617) 840-9139

John M. Frisoli [email protected] (617) 840-9139 Leverett House Mail Center 28 DeWolfe Street 304 Grove Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Westwood, MA 02090 Education Harvard College, Cambridge, MA August 2017 – present Major: Government: Courses include: Econ10a, Gov1539, Socworld44 Harvard Undergraduate Constitutional Law Society • Executive Liaison Harvard Lacrosse Team • Midfielder; Commit 40+ hours/week for a highly competitive Division 1 lacrosse program. St. Sebastian’s High School, Needham, MA September 2011 – June 2017 • National Honor Society, Finance Club, History Club, SADD • GPA: 3.4 St. Sebastian’s Football & Lacrosse • Lacrosse Team Captain, 2017 ISL Lacrosse Champions • 4 Year Letter winner, All-ISL for both football & lacrosse • United States Marine Corps Award for displaying courage and leadership Work Experience Newmark Knight Frank, Boston, MA May 2019 – August 2019 • Summer internship program for a senior brokerage team working on valuation and marketing of commercial real estate • Responsibilities included canvassing, database organization, lease comments, financial modeling and marketing materials for Newmark exclusive listings • Assisted brokers with tenant rep assignments including surveys, proposals, lease negotiations • Worked extensively on a tenant rep assignment which culminated in a Letter of Intent for a 300,000 SF lease for a new building in Boston’s Back Bay which will be the first air rights lease deal in Boston since the Copley Place development. Torrington Properties, Boston, MA May 2018 – August 2018 • Prepared and presented budgets, financial and operating reports for portfolio of properties • Assisted in apartment leasing transactions • Worked on acquisition and business plan for a 250 multi-family unit in New Hampshire • Assisted with all operations of management and leasing of 500 apartment unit portfolio. -

ARNOLD M. HOWITT, Ph.D

ARNOLD M. HOWITT, Ph.D. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation and Program on Crisis Leadership John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University 124 Mt. Auburn St. (Suite 200N, Room 266) Cambridge, MA 02138 TEL (617) 495-4571 FAX (617) 496-4062 Email: [email protected] EXPERIENCE 1976-Present HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, MA ADMINISTRATION/RESEARCH Current: Faculty Co-Director, Program on Crisis Leadership, jointly sponsored by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation and the Taubman Center for State and Local Government, John F. Kennedy School of Government (1999- present). Lead executive education programs for U.S. and international officials, conduct sponsored research projects, facilitate action research, advise graduate students and visiting fellows. Senior Adviser, Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, John F. Kennedy School of Government (2016-present). Advise Center Director and executive directors, initiate and manage special projects. Faculty chair and instructor in teaching program for senior US and international public sector executives. Previous: Executive Director, Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, John F. Kennedy School of Government (2008-2016). Academic research project development and fund raising. Program development for executive training. Research project director and senior researcher. Faculty chair and instructor in teaching programs for senior US and international public sector executives. Executive Director, A. Alfred Taubman Center for State and Local Government, John F. Kennedy School of Government (1993-2008). Associate Director (1984- 1993). (Called the State, Local, and Intergovernmental Center until 1987.) Oversight of budget, personnel, and operations. Academic research project development, fund raising, and management. -

Introduction

Introduction Introduction This student handbook is provided to inform you of the academic policies and rules of conduct that apply to resident and nonresident Summer School students. It also describes resources available at Harvard and opportuni- ties available in the Greater Boston area that will help make your summer a rewarding one. Please read the handbook carefully and keep it for reference throughout the summer. The Harvard Summer School is governed by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, which approves its curriculum and instructional staff. The academic policies and student regulations of the Summer School are consistent with those in effect during the regular academic year. The Administrative Board for Harvard Summer School decides on exceptions to the stated rules and on matters of discipline arising during the summer session. The chief administrative officer of the Summer School is the Dean of the Summer School, who is responsible for all aspects of its operation. Mat- ters relating to course enrollment, academic services, and final exams are the responsibilities of the Registrar. The Office of the Dean of Students serves as the principal source of information about Summer School policies and procedures, directs student housing and activities, and provides information on resources and activities in Cambridge and Boston. If you have questions about any of the Summer School rules, policies, or resources that are described in this handbook, please call upon the staff for assistance or advice. On behalf of the Summer School faculty and staff, I wish you a rewarding and challenging summer experience. Christopher Queen Dean of Students Student Handbook & Guide to Computing Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................... -

Special Student Procedures

Office of ALB Advising and Program Administration 51 Brattle Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3722 • (617) 495-9413 • www.extension.harvard.edu/undergraduate-degrees Special Student Procedures The Special Student option provides undergraduate degree candidates with the opportunity to enroll in Harvard College courses through the Special Student and Visiting Fellows Program sponsored by the Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. To apply, you must be an admitted undergraduate degree candidate who, at the time of application, has completed a minimum of 64 credits, 32 of which must be completed at Harvard Extension School or Harvard Summer School, with a cumulative GPA of 3.50 or higher. Of the 64 credits, a minimum of 12 credits must be in the same discipline as the proposed Harvard College course(s). The cost of FAS tuition is listed online: www.gsas.harvard.edu/programs_of_study/special_students_costs_tuition_and_fees.php There are two steps to the process: Step 1 1. Submit the attached Special Student Petition and schedule an appointment with Mark Ouchida ([email protected]), Director of Undergraduate Advising, by the deadlines: September 1 to take Harvard College courses in the spring and February 1 to take courses in the next academic year (fall and spring). 2. Mark Ouchida will review your qualifications, course selections, two faculty recommender choices, and application essay. When filling out the petition: • refrain from listing limited enrollment courses • choose recommenders who teach in the same field of your prospective course selections • focus your essay on how Harvard College courses will support your future plans and enhance your learning within your chosen field of study. -

It's Up—It's Good!

JOHN HARVard’s JournAL definite form of legitimacy there can be. It they are. They know a lot more about the I do remember looking down at my glass just clicked for me, and has been clicking college application process than I do, and of water and seeing the reflection of the ever since. seem a lot surer about what they want. vaulted ceiling dancing across the liquid’s Now, as a rising junior, I’m a proctor for I can answer some of their questions, surface. I looked up as one of my students, Harvard Summer School. I’m the primary though, and can show them where some holding his own empty glass in his hand, ex- question-answering resource for 13 rising things are and how some things work. citedly asked, “Do we get free refills?” high-school seniors. Each of them is old- My favorite question I’ve been asked so I smiled. er than I was when I first came here, one far was asked of me on one of the very first “Yes,” I answered. “The refills are most Transition Year old and completely clue- days of the Summer School term. My co- definitely free.” less about all things American. They’re full proctor and I walked some students from of questions—mostly about where classes our hall to dinner in Annenberg, where we Berta Greenwald Ledecky Undergraduate Fellow are and what Harvard life is like. They all sat together after navigating the still-con- Cherone Duggan ’14 is passionately committed to seem a lot harder working, and immense- fused crowd in the servery.