Revision of Virginia's Criminal Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Legislative Priorities 2021 Session Virginia General Assembly

State Legislative Priorities 2021 Session Virginia General Assembly N e w p o r t N e w s V i r g i n i a Virginia Senate Senator Monty Mason (D) 1st Senate District Legislative Aide: Thomas Cross District Office Pocahontas Building Office E515 PO Box 232 (804) 698-7501 Williamsburg, VA 23187 (757) 229-9310 [email protected] Committee Assignments: Agriculture, Conservation and Natural Resources General Laws and Technology Rehabilitation and Social Services Mamie E. Locke, Ph.D. (D) 2nd Senate District Legislative Aide: Theressa Parker District Office Pocahontas Building Office E510 PO Box 9048 (804) 698-7502 Hampton, VA 23670 (757) 825-5880 [email protected] Committee Assignments: Education and Health Finance and Appropriations General Laws and Technology Rehabilitation and Social Services Rules 1 Virginia House of Delegates Delegate Michael Mullin (D) 93rd District Legislative Aide: Georgia Allin District Office Pocahontas Building Office E406 566 Denbigh Boulevard, Suite C (804) 698-1093 PO Box 14011 Newport News, VA 23608 [email protected] (757) 525-9526 Committee Assignments: Courts of Justice Labor and Commerce Rules Delegate Shelly Simonds (D) 94th District Legislative Aide: Kennon Wright District Office Pocahontas Building Office E217 PO Box 1952 (804) 698-1094 Newport News, VA 23601 (757) 276-3022 [email protected] Committee Assignments: Agriculture, Chesapeake & Natural Resources Privileges and Elections Public Safety Delegate Marcia Price, (D) 95th District Legislative Aide: Tempestt Boone District Office Pocahontas Building Office W227 PO Box 196 (804) 698-1095 Newport News, VA 23607 (757) 266-5935 [email protected] Committee Assignments: General Laws Health, Welfare and Institutions Privileges and Elections Public Safety 2 Newport News City Council McKinley L. -

Legal Resources New

Virginia Legal Resources he collection strengths of the Library of Virginia are Virginia government, history, and culture. The Library serves the exe c u t i ve Tand legislative branches of government and is the main re p o s i t o ry of state government documents. Although not a law library, the Library houses a number of materials relating to the Virginia legal system. This guide compiles the key Virginia legal re s o u rces in the collection by topic and provides a brief description of the subject matter addressed by each. GENERAL SOURCES A Guide to Legal Research in Virginia. Charlottesville, Va.: Virginia CLE Publications, 2005. KFV2475 G85 2005 A step-by-step guide to legal research in the commonwealth. Michie’s Jurisprudence of Virginia and West Virginia: A Complete Treatise of Virginia and West Virginia Law. Charlottesville, Va.: Lexis Law Publishing, 1993–. Kept up-to-date by supplements and replacement volumes. KFV2465 M52 Extensive discussion and explanation of Virginia and West Virginia law. So You’re 18: A Handbook on Your Legal Rights and Responsibilities. Richmond, Va.: Virginia State Bar: Conference of Local Bar Associations, 2005. KFV2811.5 T25 S7 2005 A summary of the basic legal rights and responsibilities that come to individuals when they turn 18. Available online at http://www.vsb.org/publications/index.html#18. Bryson, Hamilton W. Virginia Law Books: Essays and Bibliographies. Philadelphia, Pa.: American Philosophical Society, 2000. KFV2401 V567 2000 A comprehensive bibliography of Virginia legal publications. VIRGINIA CONSTITUTION / CODES / REGULATIONS The Constitution of Virginia: Effective July 1, 1971, with Amendments, January 1, 2005. -

A Student Guide to Virginia's Legislative Process for Grades 6

A Student Guide to Virginia’s Legislative Process for Grades 6 and 7 Setting the Stage The Constitution of Virginia was first approved in 1776. This document outlining Virginia’s fundamental law has been completely revised on five occasions. Minor changes, also known as amendments, have been approved many more times. Changes or revisions to the Constitution of Virginia may be proposed by the Virginia General Assembly or a constitutional convention established by the legislative branch. Any changes must be approved by voters in the Commonwealth. The most-recent major revision occurred in 1971. For Example, two changes were made to the Constitution of Virginia in 2000. The first change declared the right of people to hunt, fish and harvest game. The second change established the Lottery Proceeds Fund for all revenues from any state-run lottery. Those proceeds must then be spent locally for public education. Two major components of the Constitution of Virginia are the provisions for three separate and distinct branches of state government, along with the election process for all statewide elected officials, legislators, members of local governing bodies and constitutional officers in localities. State government is divided into three branches: executive, legislative and judicial. All branches are guided by the Constitution of Virginia. EXECUTIVE BRANCH LEGISLATIVE BRANCH JUDICIAL BRANCH This branch of the This branch of the This branch of the Commonwealth executes or Commonwealth is the Commonwealth interprets carries out policy passed by General Assembly. Senators the laws that establish the the General Assembly. and Delegates establish policy. policy through legislation. Governor General Assembly Supreme Court Lieutenant Cabinet House of Senate Court of Appeals Governor Secretaries Delegates Attorney General Other Related Agencies Lower Courts A Preview of Legislative Terms AMENDMENT A change made to legislation in committee or on the chamber floor that adds to, revises, or deletes language from the legislation. -

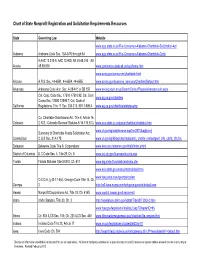

Chart of State Nonprofit Registration and Solicitation Requirements Resources

Chart of State Nonprofit Registration and Solicitation Requirements Resources State Governing Law Website www.ago.state.al.us/File-Consumer-Alabama-Charitable-Solicitation-Act Alabama Alabama Code Sec. 13A-9-70 through 84 www.ago.state.al.us/File-Consumer-Alabama-Charitable-Code 9 AAC 12.010-9. AAC 12.900; AS 45.68.010 - AS Alaska 45.68.900 www.commerce.state.ak.us/occ/home.htm www.azag.gov/consumer/charitable.html Arizona A.R.S. Sec. 44-6551, 44-6554, 44-6555 www.azsos.gov/business_services/Charities/Default.htm Arkansas Arkansas Code Ann. Sec. 4-28-401 or SB 156 www.arkleg.state.ar.us/SearchCenter/Pages/arkansascode.aspx Cal. Corp. Code Sec. 17510-17510.95; Cal. Govt www.ag.ca.gov/charities Codes Sec. 12580-12599.7; Cal. Code of California Regulations, Title 11 Sec. 300-310, 991.1-999.4 www.ag.ca.gov/charities/statutes.php Co. Charitable Solicitations Act, Title 6, Article 16, Colorado C.R.S.; Colorado Revised Statutes 6-16-110.5(3), www.sos.state.co.us/pubs/charities/charitable.htm www.ct.gov/ag/cwp/browse.asp?a=2074&agNav=| Summary of Charitable Funds Solicitation Act; Connecticut C.G.S Sec. 21A-175 www.ct.gov/ag/lib/ag/charities/public_charity_revisedgenl_info_cscfa_(2).doc Delaware Delaware Code Title 8: Corporations www.delcode.delaware.gov/title8/index.shtml District of Columbia D.C.Code Sec. 5, Title 29, Ch. 8 www.brc.dc.gov/licenses/dccode.asp Florida Florida Statutes Title XXXVI, Ch. 617 www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm www.sos.state.ga.us/securities/default.htm www.law.justia.com/georgia/codes/ O.C.G.A. -

Legal Practice Handout: Statutes — Page 2

Legal Practice Handout: Statutes Introduction Secondary sources will usually lead you to the relevant primary sources. Of the different types of primary materials, statutes, whether state or federal, are typically the first type of primary source you should consult, even before cases, as many court decisions now turn on the interpretation of statutes rather than application of common law principles. Publication of Statutes After a bill is enacted into law, it receives a “chapter” number based on the order in which it was passed and is published as a session law. Collections of session laws are arranged chronologically. While they have various names at the state level, the collection of federal session laws is known as the United States Statutes at Large. Session laws include all laws passed during the legislative session, including laws that have no general application like appropriation acts or private acts applying only to specific individuals or entities. Although session laws constitute the authoritative, binding versions of most enacted laws, researchers don’t typically turn to session laws except for historical purposes. Enacted laws of general application are next typically published in a statutory code. Codes are useful for researching statutes, as they contain only current legislation and are arranged by subject. Citations to statutes should be to the official code for your jurisdiction when available, but these official codes are sometimes unannotated. For research purposes, you will typically want to consult an annotated code, as these versions contain references to cases citing or interpreting the statute, important editorial and historical notes, and cross-references to relevant secondary sources. -

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law

William Taylor Muse Law Library University of Richmond School of Law Research Guide : Virginia Materials Introduction The Law Library has an extensive collection of materials specific to the Commonwealth of Virginia. Most of these resources are shelved with the state materials on the first floor of the library under the KFV call number. This guide briefly addresses resources involving Virginia case law, statutory law, administrative materials and legislative history. For more detailed information, please see A Guide to Legal Research in Virginia (6th ed. 2008) [available at the Circulation Desk at KFV2475 .G84 2008. Virginia Case Law Published opinions can be located using the following resources: Virginia Reports [KFV2445 .A2] - official reporter for Virginia Supreme Court decisions Virginia Court of Appeals Reports [KFV2448 .A2] - official reporter for decisions of the Virginia Courts of Appeals South Eastern Reporter (1st and 2d series) [with National Reporter System] - unofficial or regional reporter containing decisions for the Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and West Virginia courts of appeals and supreme courts Virginia Circuit Court Opinions [KFV2451.1957 .V57] - collects certain cases of first impression and additional cases in the areas of procedure, corporation law, environmental law, and the Uniform Commercial Code. - selected opinions of the general jurisdiction trial courts - circuit court opinions are of limited precedential value and typically unpublished Federal Supplement and Federal Reporter - federal -

Victims and Witnesses of Crime House Document No. 10

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. REPORT OF THE VIRGINIA STATE CRIME COMMISSION Victims and Witnesses of Crime TO THE GOVERNOR AND THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF VIRGINIA House Document No. 10 COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND 1988 140256 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice d d exactly as received from the This document has been repro uce s of view or opinions stated In person or organization Orlr~~a~~~~rs~~~ do not necessarily represent this document arle thospoe°llcie~ of the National Institute of Justice. the official pos1 t on or Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been gran~ed by, • state crime comnission VJIq:LnJ.a to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS).. Further reproduction outside 01 the NCJRS system requires permiSSion of the copyright owner. COMMONWE'ALTH of VIRGINIA POST OFFICE BOX 3·AG MEMBERS RICHMOND, VIRGINIA 23208 VIRGINIA STATE CRIME COMMISSION FROM THE SENATE OF VIRGINIA ELMON T GRA", CHAIRMAN • IN RESPONSE TO THIS LETTER TELEPHONE HOWARD P. ANDERSON (804) 225·4534 General Assembly Building WILLIAM T. PARKER ROBERT E COLVIN 910 Capitol Street FROM THE HOUSE OF DELEGATES: EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ROBERT B BALL, SR , VICE CHAIRMAN RAYMOND R. GUEST, JR. THEODORE V MORRISON, JR. A L. PHILPOTT WARREN G. STAMBAUGH CLIFTON A. WOODRUM APPOINTMENTS BY THE GOVERNOR L. RAY ASHWORTH WILLIAM N PAXTON, JR. GEORGE F RICKETTS, SR ATTORNEY GENERAL'S OFFICE H LANE KNEEDLER November 9, 1987 Xo: The Honorable Gerald L. Baliles, Governor of Virginia, and Members of the General Assembly: House Joint Resolution 225, agreed to by the 1987 General Assembly, directed the Virginia State Crime Commission "to evaluate the effectiveness of current services provided to victims and witnesses of crime throughout the Commonwealth of Virginia and make any recommendations the Commission finds appropriate." In fulfilling this directive, a comprehensive study was conducted by the Virginia State Crime Commission. -

VIRGINIA) by Fred Dingledy January, 2014

AALL LISP PUBLIC LIBRARIES TOOLKIT STATE INFORMATION (VIRGINIA) by Fred Dingledy January, 2014 1. Constitution of Virginia Online The Commonwealth of Virginia makes its constitution available through its website at http://constitution.legis.virginia.gov/ Print Can be found in the Constitutions volume of the print Code of Virginia 1950 (below) and in Volume 1 (Constitutions) of West’s Annotated Code of Virginia (below). 2. State Code (statutes) Online The Commonwealth of Virginia makes an unannotated version of its statutory code available through its Legislative Information System (LIS) at http://lis.virginia.gov/000/src.htm. They usually do a good job of keeping the code on the website up to date. The State Decoded project, an independent effort to make freely-available state codes that are more user-friendly, has released a version of the Virginia code called Virginia Decoded, available at http://vacode.org/. This version of the code includes pop-up definitions, cross-references to other code sections, and references to court decisions interpreting code sections. Virginia Decoded is currently in beta, and this is not an official version of the code, but has handy research tools that would normally require using a pay service. Print You have two choices of annotated codes in Virginia: - LexisNexis’s Code of Virginia 1950 (Va. Code Ann.). This is also known as “Michie’s Code”, since it used to be published by Michie (pronounced like “Mickey”), which LexisNexis bought. - West’s Annotated Code of Virginia (Va. Code Ann. (West)). 3. State bills and session laws Online Bills and session laws are available online via the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Legislative Information System (LIS) at http://lis.virginia.gov/lis.htm. -

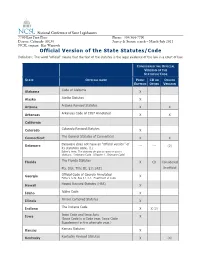

Official Version of the State Statutes/Code Definition: the Word "Official" Means That the Text of the Statutes Is the Legal Evidence of the Law in a Court of Law

National Conference of State Legislatures 7700 East First Place Phone: 303/364-7700 Denver, Colorado 80230 Survey & Statute search – March-July 2011 NCSL contact: Kae Warnock Official Version of the State Statutes/Code Definition: The word "official" means that the text of the statutes is the legal evidence of the law in a court of law. CONSIDERED THE OFFICIAL VERSION OF THE STATUTES/CODE STATE OFFICIAL NAME PRINT CD OR ONLINE EDITION OTHER VERSION Alabama Code of Alabama X Alaska Alaska Statutes X Arizona Arizona Revised Statutes X X Arkansas Arkansas Code of 1987 Annotated X X California Colorado Colorado Revised Statutes X Connecticut The General Statutes of Connecticut X X Delaware Delaware does not have an “official version” of --- --- (2) its statutory code. (1) Editor’s note: The statutes do give a name to use in citations. Delaware Code (Chapter 1. Delaware Code) Florida The Florida Statutes X CD Considered Fla. Stat. Title III, §11.2421 Unofficial Georgia Official Code of Georgia Annotated X Editor’s note: See § 1-1-1. Enactment of Code Hawaii Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) X Idaho Idaho Code X Illinois Illinois Compiled Statutes X Indiana The Indiana Code X X (3) Iowa Iowa Code and Iowa Acts X (Iowa Code in a Code year. Iowa Code Supplement in the alternate year.) Kansas Kansas Statutes X Kentucky Kentucky Revised Statutes X (4) CONSIDERED THE OFFICIAL VERSION OF THE STATUTES/CODE STATE OFFICIAL NAME PRINT CD OR ONLINE EDITION OTHER VERSION Louisiana West's Louisiana Statutes Annotated X Editor’s note: See RS 1:1 §1. -

Council of State Governments Capitol

THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS SEPT 2011 CAPITOL RESEARCH SPECIAL REPORT Public Access to Official State Statutory Material Online Executive Summary As state leaders begin to realize and utilize the incredible potential of technology to promote trans- parency, encourage citizen participation and bring real-time information to their constituents, one area may have been overlooked. Every state provides public access to their statutory material online, but only seven states—Arkansas, Delaware, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, Utah and Vermont—pro- vide access to official1 versions of their statutes online. This distinction may seem academic or even trivial, but it opens the door to a number of questions that go far beyond simply whether or not a resource has an official label. Has the information online been altered—in- tentionally or not—from its original form? Who is in March:2 “You’ve often heard it said that sunlight is responsible for mistakes? How often is it updated? the best disinfectant. And the recognition is that, for Is the information secure? If the placement of a re- us to do better, it’s critically important for the public source online is not officially mandated or approved to know what we’re doing.” by a statute or rule, its reliability and accuracy are At the most basic level, free and open public access difficult to gauge. to the law that governs this country—federal and As state leaders have moved quickly to provide state—is necessary to create the transparency that is information electronically to the public, they may fundamental to a functional participatory democracy. -

Employment Law Robert T

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 25 | Issue 4 Article 11 1991 Annual Survey of Virginia Law: Employment Law Robert T. Billingsley Thomas J. Dillon III Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert T. Billingsley & Thomas J. Dillon III, Annual Survey of Virginia Law: Employment Law, 25 U. Rich. L. Rev. 759 (1991). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol25/iss4/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMPLOYMENT LAW Robert T. Billingsley* Thomas J. Dillon, III** I. INTRODUCTION This article surveys the judicial and legislative developments in Virginia employment law between June 1990 and June 1991. De- velopments in the areas of worker's compensation and unemploy- ment compensation, each of which has its own distinctive body of law, are outside the scope of this article. During the period covered by this article there were few signifi- cant judicial developments in the area of employment law. Several cases dealt with the topic of wrongful discharge, with both the Su- preme Court of Virginia and Virginia's circuit courts adding to the growing body of law in this area. The courts also continued to wrestle with the reasonableness test for covenants not to compete. But, the most extensive developments in the area of employment law area occurred in the legislative arena. -

1999 Code of Virginia, Title 9, Chapter 1.1:1, Virginia Administrative

1999 Code of Virginia Excerpt Title 9 - Commissions, Boards and Institutions Generally Chapter 1.1:1 - Administrative Process Act - Article 1 - General Provisions §§ 9-1 through 9-6 Repealed by Acts 1952, c. 703. §§ 9-6.1 through 9-6.14 Repealed by Acts 1975, c. 503. § 9-6.14: 1 Short title This chapter may be cited as the "Administrative Process Act." § 9-6.14:2 Effect of repeal of the General Administrative Agencies Act and enactment of this chapter A. The repeal of Chapter 1.1 (§ 9-6.1 et seq.) of this title, which is entitled the General Administrative Agencies Act but which will be hereinafter referred to as Chapter 1.1, shall in no way affect the validity of any regulation that has been adopted and promulgated under Chapter 1.1 prior to the effective date of this chapter.- B. Whenever any reference is made in this Code to the General Administrative Agencies Act, the applicable provisions of this chapter are substituted therefor. ( § 9-6.14:3 Policy The purpose of this chapter is to supplement present and future basic laws conferring authority on agencies either to make regulations or decide cases as well as to standardize court review thereof save as laws hereafter enacted may otherwise expressly provide. This chapter does not supersede or repeal additional procedural requirements in such basic laws. § 9-6.14:4 Definitions As used in this chapter: "Agency" means any authority, instrumentality, officer, board or other unit of the state government empowered by the basic laws to make regulations or decide cases.