5. Whose Sword Is It, Anyway?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Classic Novels: Meeting the Challenge of Great Literature Parts I–III

Classic Novels: Meeting the Challenge of Great Literature Parts I–III Professor Arnold Weinstein THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Arnold Weinstein, Ph.D. Edna and Richard Salomon Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature, Brown University Born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1940, Arnold Weinstein attended public schools before going to Princeton University for his college education (B.A. in Romance Languages, 1962, magna cum laude). He spent a year studying French literature at the Université de Paris (1960−1961) and a year after college at the Freie Universität Berlin, studying German literature. His graduate work was done at Harvard University (M.A. in Comparative Literature, 1964; Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, 1968), including a year as a Fulbright Scholar at the Université de Lyon in 1966−1967. Professor Weinstein’s professional career has taken place almost entirely at Brown University, where he has gone from Assistant Professor to his current position as Edna and Richard Salomon Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature. He won the Workman Award for Excellence in Teaching in the Humanities in 1995. He has also won a number of prestigious fellowships, including a Fulbright Fellowship in American literature at Stockholm University in 1983 and research fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1998 (in the area of literature and medicine) and in 2007 (in the area of Scandinavian literature). In 1996, he was named Professeur Invité in American literature at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Professor Weinstein’s -

Literary Tricksters in African American and Chinese American Fiction

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction Crystal Suzette anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, and the Ethnic Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Crystal Suzette, "Far from "everybody's everything": Literary tricksters in African American and Chinese American fiction" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623988. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-z7mp-ce69 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

The Rogues Proposal Free

FREE THE ROGUES PROPOSAL PDF Jennifer Haymore | 416 pages | 19 Nov 2013 | Little, Brown & Company | 9781455523375 | English | New York, United States Rogues (comics) - Wikipedia This loose criminal The Rogues Proposal refer to themselves as the Roguesdisdaining the use of The Rogues Proposal term "supervillain" or "supercriminal". The Rogues, compared to similar collections of supervillains in the DC Universeare an unusually social group, maintaining a code of The Rogues Proposal as The Rogues Proposal as high standards for acceptance. No Rogue may inherit another Rogue's identity a "legacy" villain, for example while the original still lives. Also, simply acquiring a former Rogue's costume, gear, or abilities is not sufficient to become a Rogue, even if the previous Rogue is already dead. The Rogues Proposal do not kill anyone unless it is absolutely necessary. Additionally, the Rogues refrain from drug usage. Although they tend to lack the wider name recognition of the villains who oppose Batman and Supermanthe enemies of the Flash form a distinctive rogues gallery through their unique blend of colorful costumes, diverse powers, and unusual abilities. They lack any one defining element or theme between them, and have no significant ambitions in their criminal enterprises beyond relatively petty robberies. The Rogues are referenced by Barry Allen to have previously been defeated by him and disbanded. A year prior, Captain Cold, Heat Wave, the Mirror Master Sam Scudder againand the Weather Wizard underwent a procedure at an unknown facility that would merge them with their weapons, giving them superpowers. The procedure went awry and exploded. Cold's sister Lisa, who was also at the facility, was caught in the explosion. -

Instruction Manual and Adventurek1s Journal Table of Contents Limited Warranty Introduction

INSTRUCTION MANUAL AND ADVENTUREK1S JOURNAL TABLE OF CONTENTS LIMITED WARRANTY INTRODUCTION ........... .. ... ..... ..... .... .......... ... .. ........... ... .. ... .. .......... ............ ............... .. ..... .... ....... .....1 Your Cjame Box Should Contain ..... .... .. .. .. .. ................... .. .. .. .... ....... .. ..... .. ... ....................................1 SSI MAKES NO WARRANTIES, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, WITH RESPECT TO THE SOFlWARE PRO Transferring Characters from DEATH KNIQHTSO F KRYNN ............. .. .............. ............................ .. .......... .1 GRAM RECORDED ON THE DISKITTE OR THE GAME DESCRIBED IN THIS RULE BOOK, THEIR QUALITY, Before You Play ..................... ................... ..................................................... .... .......... ............................1 PERFORMANCE, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PARTICULAR PURPOSE. THE PROGRAM (jetting Started Quickly ......... ..... ........... .. ........................................................................ .. .. .................... 1 Using Menus ......... .. .... .. ............ .. ................................................................................... ................. ........1 AND GAME ARE SOLD 'AS IS.' THE ENTIRE RISK AS TO THEIR QUALITY AND PERFORMANCE IS WITH THE BUYER. IN NO EVENT WILL SSI BE LIABLE FOR DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUEN BEQINNIN(j TO PlAY ................ .... .. .............. .. ........ .. ...... .. ........................... .. ............................. -

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Faya Causey With technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES This catalogue was first published in 2012 at http: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data //museumcatalogues.getty.edu/amber. The present online version Names: Causey, Faya, author. | Maish, Jeffrey, contributor. | was migrated in 2019 to https://www.getty.edu/publications Khanjian, Herant, contributor. | Schilling, Michael (Michael Roy), /ambers; it features zoomable high-resolution photography; free contributor. | J. Paul Getty Museum, issuing body. PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads; and JPG downloads of the Title: Ancient carved ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum / Faya catalogue images. Causey ; with technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling. © 2012, 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Description: Los Angeles : The J. Paul Getty Museum, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “This catalogue provides a general introduction to amber in the ancient world followed by detailed catalogue entries for fifty-six Etruscan, Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Greek, and Italic carved ambers from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a The volume concludes with technical notes about scientific copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4 investigations of these objects and Baltic amber”—Provided by .0/. Figures 3, 9–17, 22–24, 28, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 51, and 54 are publisher. reproduced with the permission of the rights holders Identifiers: LCCN 2019016671 (print) | LCCN 2019981057 (ebook) | acknowledged in captions and are expressly excluded from the CC ISBN 9781606066348 (paperback) | ISBN 9781606066355 (epub) BY license covering the rest of this publication. -

Icelandic Folklore

i ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE ii BORDERLINES approaches,Borderlines methodologies,welcomes monographs or theories and from edited the socialcollections sciences, that, health while studies, firmly androoted the in late antique, medieval, and early modern periods, are “edgy” and may introduce sciences. Typically, volumes are theoretically aware whilst introducing novel approaches to topics of key interest to scholars of the pre-modern past. iii ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE by ERIC SHANE BRYAN iv We have all forgotten our names. — G. K. Chesterton Commons licence CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. This work is licensed under Creative British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2021, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds The author asserts their moral right to be identi�ied as the author of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted determinedprovided that to thebe “fair source use” is under acknowledged. Section 107 Any of theuse U.S.of material Copyright in Act this September work that 2010 is an Page exception 2 or that or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/ 29/ EC) or would be 94– 553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. satis�ies the conditions speci�ied in Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. ISBN (HB): 9781641893756 ISBN (PB): 9781641894654 eISBN (PDF): 9781641893763 www.arc- humanities.org print-on-demand technology. -

The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses Into Historic Age Witches and Monsters

The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses Miriam Robbins Dexter Special issue 2011 Volume 7 The Monstrous Goddess: The Degeneration of Ancient Bird and Snake Goddesses into Historic Age Witches and Monsters Miriam Robbins Dexter An earlier form of this paper was published as 1) to demonstrate the broad geographic basis of “The Frightful Goddess: Birds, Snakes and this iconography and myth, 2) to determine the Witches,”1 a paper I wrote for a Gedenkschrift meaning of the bird and the snake, and 3) to which I co-edited in memory of Marija demonstrate that these female figures inherited Gimbutas. Several years later, in June of 2005, the mantle of the Neolithic and Bronze Age I gave a lecture on this topic to Ivan Marazov’s European bird and snake goddess. We discuss class at the New Bulgarian University in who this goddess was, what was her importance, Sophia. At Ivan’s request, I updated the paper. and how she can have meaning for us. Further, Now, in 2011, there is a lovely synchrony: I we attempt to establish the existence of and have been asked to produce a paper for a meaning of the unity of the goddess, for she was Festschrift in honor of Ivan’s seventieth a unity as well as a multiplicity. That is, birthday, and, as well, a paper for an issue of although she was multifunctional, yet she was the Institute of Archaeomythology Journal in also an integral whole. In this wholeness, she honor of what would have been Marija manifested life and death, as well as rebirth, and Gimbutas’ ninetieth birthday. -

A Lifetime of Trouble-Mai(Ing: Hermes As Trici(Ster

FOUR A LIFETIME OF TROUBLE-MAI(ING: HERMES AS TRICI(STER William G. Doty In exploring here some of the many ways the ancient Greek figure of Hermes was represented we sight some of the recurring characteristics of tricksters from a number of cultures. Although the Hermes figure is so complex that a whole catalog of his characteristics could be presented,1 the sections of this account include just six: (1) his marginality and paradoxical qualities; (2) his erotic and relational aspects; (3) his func tions as a creator and restorer; (4) his deceitful thievery; (5) his comedy and wit; and (6) the role ascribed to him in hermeneutics, the art of interpretation whose name is said to be derived from his. The sixth element listed names one of the most significant ways this trickster comes to us-as interpreter, messenger-but the other characteristics we will explore provide important contexts for what is conveyed, and how. This is not just any Western Union or Federal Express worker, but a marginal figure whose connective tasks shade over into creativity itself. A hilarious cheat, he sits nonetheless at the golden tables of the deities. We now recognize that even apparently irreverent stories show that some mythical models could be conceived in a wide range of sig nificances, even satirized, without thereby abandoning the meaning complex in which the models originated. For example an extract from a satire by Lucian demonstrates that Hermes could be recalled with re Copyright © 1993. University of Alabama Press. All rights reserved. of Alabama Press. © 1993. University Copyright spect, as well as an ironic chuckle: Mythical Trickster Figures You :are Contours, reading Contexts, copyrighted and material Criticisms, published edited by Williamthe University J. -

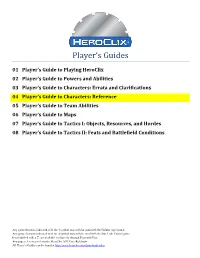

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Dragon Magazine

D RAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan We’ll say it again Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Contents From time to time in the past, this Gali Sanchez Vol. VII, No. 8 January 1983 Roger Raupp magazine has proclaimed its editorial Patrick L. Price independence. “We’re not a house or- SPECIAL ATTRACTION Business manager: Debra Chiusano gan,” we have stated before, beginning Office staff: Sharon Walton in a time when many of our competitors ARRAKHAR’S WAND. 45 Pam Maloney in the field could justifiably be called Product design: Eugene S. Kostiz that. We pointed this out because it Finders aren’t always keepers: Layout designer: Ruth M. Hodges A new fantasy boardgame seemed the point needed to be made. Contributing editors: Roger Moore We haven't talked about the subject Ed Greenwood OTHER FEATURES National advertising representative: lately because there didn’t seem to be a Robert LaBudde & Associates, Inc. need to. What we did backed up what we A special section: 2640 Golf Road said, and the turn of events in the gaming Glenview IL 60025 industry made the topic unimportant for Runes — in history . 6 Phone (312) 724-5860 Runestones — in fantasy. 12 comparative purposes; no sense beating Be Quest — and in fiction. 16 This issue’s contributing artists: a dead issue. Clyde Caldwell Jim Holloway Which brings us to the recent past — Castles by Carroll . 19 Roger Raupp Larry Elmore DRAGON™ issues #65 and #66, wherein II: Wawel Castle Mike Carroll Phil Foglio some opinionated remarks by E. Gary Jeff Easley Dave Trampier Gygax appeared.