Bernstein & Gershwin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

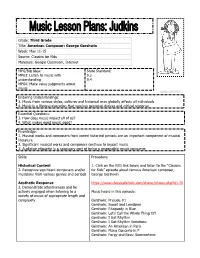

Grade: Third Grade Title: American Composer: George Gershwin Week: May 11-15 Source: Classics for Kids Materials: Google Classroom, Internet

Grade: Third Grade Title: American Composer: George Gershwin Week: May 11-15 Source: Classics for Kids Materials: Google Classroom, Internet MPG/Big Idea: State Standard: MPG3: Listen to music with 9.2 understanding 9.4 MPG4: Make value judgments about music Enduring Understandings: 3. Music from various styles, cultures and historical eras globally affects all individuals 4. Music is a lifelong avocation that requires personal choices and critical response Essential Questions: 3. How does music impact all of us? 4. What makes good music good? Knowledge: 1. Musical works and composers from varied historical periods are an important component of musical literature 3. Significant musical works and composers continue to impact music 3. Audience etiquette is a necessary part of being a responsible music consumer Skills: Procedure: Historical Context 1. Click on the RED link below and listen to the “Classics 2. Recognize significant composers and/or for Kids” episode about famous American composer, musicians from various genres and periods George Gershwin Aesthetic Response https://www.classicsforkids.com/shows/shows.php?id=70 3. Demonstrate attentiveness and be actively engaged when listening to a Music heard in this episode: variety of music of appropriate length and complexity Gershwin: Prelude #1 Gershwin: Sweet and Lowdown Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue Gershwin: Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off Gershwin: I Got Rhythm Gershwin: I Got Rhythm Variations Gershwin: An American in Paris Gershwin: Piano Concerto in F Gershwin: Porgy and Bess: Summertime 2. When finished complete the assignment on the Google Form below Assessment: Answer the multiple-choice questions by using the BLUE link below to open the Google form: https://forms.gle/VMryZf38P3rTPYL8A George Gershwin was born in a. -

EMR 30514 Concerto in F Minor Händel Trombone & Piano

Concerto in F Minor + Trombone ( ) & Piano / Organ Arr.:> Ted Barclay Georg Friedrich Händel EMR 30514 Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch Concerto in F Minor | Photocopying Georg Friedrich Händel is illegal! (1685 - 1759) original - Concerto for Oboe Arr.: Ted Barclay Grave e = 80 Trombone Organ / Piano f 3 6 mf a piacere mp fp colla parte mp mp 9 cresc. p cresc. p EMR 30514 © COPYRIGHT BY EDITIONS MARC REIFT CH-3963 CRANS-MONTANA (SWITZERLAND) www.reift.ch ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT SECURED 4 12 f 15 A tempo p a piacere ten. p fp colla parte p ten. 18 p p -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2011 Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra Timothy Patrick Cooper [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Timothy Patrick, "Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/964 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Timothy Patrick Cooper entitled "Concerto for Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Kenneth A. Jacobs, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Brendan P. McConville, Daniel R. Cloutier Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Concerto For Bassoon and Chamber Orchestra A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Timothy Patrick Cooper August 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Timothy Cooper. All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Several individuals deserve credit for their assistance in this project. -

Kansas State University Orchestra Programs 1990—2018 Updated January 13, 2018 David Littrell, Conductor

Kansas State University Orchestra Programs 1990—2018 updated January 13, 2018 David Littrell, conductor 1990-1991 October 16, 1990 Tragic Overture, Op. 81 Brahms Oboe Concerto R. Strauss Dr. Sara Funkhouser, oboe Symphony No. 4 in C Minor (“Tragic”) Schubert December 11, 1990 Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 JS Bach “Vedrai, carino” from Don Giovanni Mozart Dayna Snook, mezzo-soprano Scaramouche Suite, 2nd & 3rd mvts. Milhaud Christopher Goins, alto saxophone “Son vergin vezzosa” from I Puritani Bellini Ai-ze Wang, soprano Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 Shostakovich April 4-5-6, 1991 The Magic Flute (Opera) Mozart April 23, 1991 Overture to Ruy Blas Mendelssohn Symphony No. 101 in D Major (“Clock”) Haydn Symphony No. 5 in Eb Major, Op. 82 Sibelius 1991-1992 October 1, 1991 Overture to Il Signor Bruschino Rossini Concerto Grosso for Four String Orchestras Vaughan Williams assisting musicians: Manhattan public school string students Symphony No. 2 in B Minor Borodin repeat performance October 2, 1991 at Concordia KS October 24-25-26, 1991 West Side Story Bernstein December 9, 1991 In Memoriam, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sinfonia concertante in Eb Major, K. 364 Mozart Cora Cooper, violin Melinda Scherer Bootz, viola Requiem, K. 626 Mozart John Alldis, guest conductor soloists: Lori Zoll, Juli Borst, Rob Fann, Andy Stuckey KSU Concert Choir March 3, 1992 Overture to Der Freischütz von Weber “Faites-lui mes aveux” from Faust Gounod Juli Borst, mezzo-soprano “Ah, per sempre” from I Puritani Bellini Andy Stuckey, baritone Concerto in D Haydn Lisa Leuthold, horn Symphony No. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

A Gershwin Centennial Celebration

be nnington c oll e ge pres e nts A GERSHWIN CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION F RIDA V SATURDA V SUNDAV DECEMBER II - 13TH, 1998; 8:00PM MATINEE SATURDA V, 2:00PM I GOT RHYTHM EXCEPTIONAL YET LESSER-KNOWN PIECES B Y GEORGE GERSHW IN SusAN A. GREENWALL WoRKSHOP AMY WILLIAMS AND ALLEN SHAWN PIANO THA T S w EET AND L ow DowN T wo W A LTZES INC IMPROMPTU IN T WO KEYS · PRELUDE (MELODY #17) I G o T RHYTH M V ARIA TIONS (1930) WITH BRUCE WILLIAMSO/'.J PLAYING GERS H W IN STANOARDS ON THE UPRIG HT R EFR E SHME NTS AVAILABLE BLUE ,.. ·MoNDAY BY GEORGE GERSHWIN . MJsic DRECTCP ANJ C~TCP 8TAGE DRECTCP ANJ CosTUvE DESIGI'ER IDA FAIELLA DANIEL MCHAELS~ ScEi'Jc DES!Gi'ER L.JGI--rrNG DESIGI'ER PETER SEWARD MCHAEL GIANNITTI ~1--ESTPAL REALIZA TlON PRooucTJON 8TAG E MANAG~ PHLIPSALATHE STEVEESPACH CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE) M IKE M ATTHEW P ILLISCHER SAM R YAN B AROLET-FOGARTY --JoE D u FFY H AVENS T oM M ATTHE W F oLLETTE V1 CAMILLE H ARTMAN D ANCERS C A YLI C AVACO ANNA ZIMMER KELLEY B RYANT 0:::<CHESTRA P iANO NATHAN --JEW ViOLIN I B ARRY FiNCLAIR ViOLIN II BRONWE N D AVIE S -MASON ViOLA S ARA CRONAN CELLO I MICHAEL CLOSE CELLO II MELISSA COLLINS B ASS P HILIP S ALAT HE T ENOR SAX B RUCE WILLIAMSON A LTO SAx --JENNIFER D ovLE-BEcK T RUMPET R oNALD ANDERSON PERCUSSION 0 ESSE0LSEN At the centennial of his birth, Brooklyn-born composer George Gershwin remains one of America's most intriguing cultural figures. -

May, 2020 No. 1940 Subscription (Program C) George Gershwin

May, 2020 ◎No. 1940 Subscription (Program C) ◎ ■George Gershwin (1898–1937) ■Concerto in F (31') The sound of the works by the early twentieth-century American composer and pianist George Gershwin is unique. It is different from that of the compositions of the well- known composers of the time. Some European musicians like Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy incorporated into their music Jazz elements, but they never reached Gershwin’s level of integrating extremely different types of music. George Gershwin was born in Brooklyn, New York, on September 26, 1898. He did not receive music lessons until he was thirteen years old but was already working as a pianist two years later. Around this time, he started to write songs. In the 1920s, together with his older brother Ira (lyricist), Gershwin composed a considerable amount of music for Broadway theaters. He also had strong interests in writing serious music, of which his first major work was Rhapsody in Blue for orchestra and piano, composed in 1924. Gershwin began to compose Concerto in F for solo piano and orchestra in May 1925 and completed it on November 10 that year. The piece was commissioned by Walter Damrosch, a conductor/composer who directed the New York Symphony Orchestra. The first performance took place on December 3, 1925, with Gershwin playing the solo piano. Gershwin mixed elements of jazz, Broadway songs and dances, and late-romantic sonority and harmony to create the Concerto, which comprises three movements. It begins with four timpani notes in a descending arpeggio-like manner (F, C, F, and F). -

GEORGE GERSHWIN Born 26 September 1898 in Brooklyn, New York; Died 12 July 1937 in Hollywood, California

GEORGE GERSHWIN Born 26 September 1898 in Brooklyn, New York; died 12 July 1937 in Hollywood, California. An American in Paris (1928) PREMIERE OF WORK: New York, 13 December 1928; Carnegie Hall; New York Philharmonic; Walter Damrosch, conductor PSO PREMIERE: 19 November 1933; Syria Mosque; Antonio Modarelli, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 17 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: piccolo, three flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, three saxophones, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (including four taxi horns), celesta and strings. In 1928, George Gershwin was not only the toast of Broadway, but of all America, Britain and many spots in Europe, as well: he had produced a string of successful shows (Rosalie and Funny Face were both running on Broadway that spring), composed two of the most popular concert pieces in recent memory (Rhapsody in Blue and the Piano Concerto in F), and was leading a life that would have made the most glamorous socialite jealous. The pace-setting Rhapsody in Blue of 1924 had shown a way to bridge the worlds of jazz and serious music, a direction Gershwin followed further in the exuberant yet haunting Piano Concerto in F the following year. He was eager to move further into the concert world, and during a side trip in March 1926 to Paris from London, where he was preparing the English premiere of Lady Be Good, he hit upon an idea, a “walking theme” he called it, that seemed to capture the impression of an American visitor to the city “as he strolls about, listens to the various street noises, and absorbs the French atmosphere.” He worried that “this melody is so complete in itself, I don’t know where to go next,” but the purchase of four Parisian taxi horns on the Avenue de la Grande Armée inspired a second theme for the piece. -

The Bravo! Vail Music Festival, in Collaboration with The

THE BRAVO! VAIL MUSIC FESTIVAL, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE NATIONAL REPERTORY ORCHESTRA, PRESENTS TWO PERFORMANCES OF ITS ANNUAL FREE FAMILY CONCERT, GERSHWIN’S MAGIC KEY, A CLASSICAL KIDS MUSIC EDUCATION PRODUCTION, ON WEDNESDAY, JULY 12 For the first time in its thirty-year history, Bravo Vail! presents two performances of its free family concert: up valley, at the Gerald R. Ford Amphitheater in Vail; and down valley, at the Lundgren Amphitheater in Gypsum; with Bravo! Vail's popular Instrument Petting Zoo an hour before each concert. Kensho Watanabe, assistant conductor of The Philadelphia Orchestra, leads the National Repertory Orchestra during both performances. Vail, CO (FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE) – On Wednesday, July 12, Bravo! Vail and the National Repertory Orchestra present Gershwin’s Magic Key, a Classical Kids Music Education production, in two perforMances, at the Gerald R. Ford Amphitheater in Vail at 11:00 a.M. and the Lundgren Amphitheater in GypsuM at 6:00 p.m. Having served the Vail Valley coMMunity for the past thirty years, the Bravo! Vail Music Festival is expanding its educational and outreach activities in order to Make classical Music and its nuMerous benefits accessible to as wide and diverse a local audience as possible. This suMMer, for the first tiMe ever, Bravo! Vail is adding a second performance of its popular annual free faMily concert in GypsuM, to reach faMilies down valley. Gershwin’s Magic Key features Colorado’s prestigious National Repertory Orchestra, led by The Philadelphia Orchestra’s assistant conductor, Kensho Watanabe, Magically weaving the tale of a chance encounter between a newspaper boy and the coMposer hiMself on the streets of New York. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Music Director

Program One HundRed TWenTy-FiRST SeASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Tuesday, May 15, 2012, at 1:30 Thursday, May 17, 2012, at 8:00 Jaap van Zweden Conductor gene Pokorny Tuba Shostakovich Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a Largo— Allegro molto— Allegretto— Largo— Largo Vaughan Williams Tuba Concerto Prelude: Allegro moderato Romanza: Andante sostenuto Finale (Rondo all tedesca): Allegro Gene POkORny IntermISSIon Beethoven Symphony no. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Poco sostenuto—Vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio This evening’s concert is generously sponsored in part by the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation. Wednesday, May 16, 2012, at 6:30 (Afterwork Masterworks, performed with no intermission) Jaap van Zweden Conductor gene Pokorny Tuba Shostakovich Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a Vaughan Williams Tuba Concerto in F Minor Beethoven Symphony no. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to WBBM Newsradio 780 and 105.9 FM for its generous support as the media sponsor for the Afterwork Masterworks series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommentS by PHiLLiP HuSCHeR Dmitri Shostakovich Born September 25, 1906, Saint Petersburg, Russia. Died August 9, 1975, Moscow, Russia. Chamber Symphony for Strings in C minor, op. 110a n the summer of 1960, in just three days, is his Eighth, IShostakovich went to Dresden to and it is one of the most powerful write the score for a new film by the and personal works of twentieth- director Lev Arnshtam. -

Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2020 Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star Caleb Taylor Boyd Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Caleb Taylor, "Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star" (2020). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2169. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/2169 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Todd Decker, Chair Ben Duane Howard Pollack Alexander Stefaniak Gaylyn Studlar Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star by Caleb T. Boyd A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 St. Louis, Missouri © 2020, Caleb T. Boyd Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................