Streets Are Not Enough: the Introverted Block As a Neglected Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability Report National Sustainability Report 2016

NATIONAL REAL ESTATE ADVISORS 2016 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT NATIONAL SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2016 OUR OUTLOOK National Real Estate Advisor’s (“National”) consistent commitment to continuous process is committed to creating well-paying jobs and investment policies and approach include improvement, National went through a strategic providing access to healthy work spaces. sustainable development and management planning process in 2016 to further define our Most importantly, we provide challenging and practices to help realize long-term investment Environmental, Social, and Governance (or ESG) meaningful work to our employees who in turn returns through more efficient operations and approach. This effort included an evaluation enable our organization to make a difference in healthier, more attractive building environments and even deeper commitment to stakeholder the lives of the people and communities in which for tenants and their employees. With a engagement, which ultimately means National we work, live, and invest. ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND GOVERNANCE National has expanded its commitment to programs, and performance and is a relative constructed to green building standards, with enhance environmental, social, and governance benchmark assessing the ESG performance of real LPM Apartments (Minneapolis, MN), Confluence policies related to its portfolio management and estate portfolios globally. In 2016, several National Apartments (Denver, CO), 3737 Buffalo Speedway states these commitments in the company’s projects received green building certifications and (Houston, TX), 167 W. Erie (Chicago, IL), East sustainability policy. As an investment manager, ratings. 2929 Weslayan (LEED® Gold), Bainbridge Market (Philadelphia, PA) and Field Office National achieved its second Green Star recognition Bethesda (LEED® Silver) and Bainbridge Shady (Portland, OR) all registered with the goal of LEED® (achieving 3 of 5 possible Green Stars) from the Grove (Green Globes) received their certifications. -

Planning Commission Meeting October 15, 2019 Recap of Process- History

SIA - Phase 1A:Form-Based Code Planning Commission Meeting October 15, 2019 Recap of Process- History ❑ Sept. 2017: Hold kick-off charrette in the SIA ❑ Dec. 2017: Submit first draft of FBC ❑ Mar. 2018: Submission of Second Draft of FBC ❑ April 2018: Submit housing needs assessment & financial analysis of affordable housing options ❑ June 2018: Housing Assessment Presentation to City Council ❑ Sept. 2018 Hold community engagement workshops with public housing residents to discuss FBC and housing strategy ❑ Sept. 2018: Review Friendship Court site plan and meet with PHA leadership ❑ April 2019: Meeting with CRHA and PHRA Boards ❑ Aug. 2019: Hold work session with City Council & Planning Commission ❑ Sept. 2019: Hold two stakeholder open houses and consolidate feedback on draft ❑ Oct. 2019: Submit final draft of FBC to NDS ❑ Oct. 2019: Presentation to Planning Commission Tonight’s Presentation ❑ The basics of FBCs ❑ Explain the contents of proposed FBC ❑ Get direction on outstanding issues ❑ Hear concerns and answer questions Form Based Codes ➢ A recap of the basics What is included in a Form-Based Code? Four common factors: • Regulating plan (zoning map), • Building type/use and form, • Open space considerations, • Design and function of streets. In broad strokes, the type, size, and scale of desired private and public development. Code aspirations Potential Benefits of FBCs ✓ Make it easier to walk, bike, use transit ✓ Set standards for community scale and character ✓ Integrate uses better ✓ Offer more cohesive design and development ✓ -

City Block Development Project: Frequently Asked Questions

City Block Development: Frequent Asked Questions October 22, 2019 City Block Development Project: Frequently Asked Questions 1. What is the City Block Project? City Block is a new, 3-acre multi-use development project in Downtown Paducah. The Project includes a new destination hotel, two mixed-use residential/retail buildings, a public town square, and public off-street parking. 2. Where is City Block Project located? City Block is located on a city-owned Site bounded by Broadway, Jefferson, Water and Second Streets in Downtown Paducah. The Site is currently used for off-street public parking. 3. Who is leading the Project? City Block is a joint partnership between the City of Paducah, the land owner, and Weyland Ventures, a multi-disciplinary real estate development firm based in Louisville. Weyland Ventures is known for creating unique mixed-use properties in urban areas across the nation through the use of state and federal historic tax credits, new market tax credits, and other layered financing tools. Weyland Ventures’ projects incorporate residential, commercial, retail, and entertainment venues to create new and vibrant neighborhoods while preserving a community’s unique characteristics and heritage. Notable projects include Whiskey Row Lofts, the Slugger Museum and Factory in Louisville, and Owensboro’s Downtown and Riverfront Revitalization. 4. What is the agreement between the City of Paducah and Weyland Ventures? In April 2019, the City of Paducah entered into a 12-month preliminary development agreement with Weyland Ventures to undertake planning, design, and development activities for the City Block site. As part of this agreement, the City agreed to undertake due diligence work, including environmental review, geotechnical analysis, a utility assessment, and a parking assessment. -

Developments Introduction 1

2019 CENTER CITY PHILADELPHIA DEVELOPMENTS INTRODUCTION 1 DEVELOPMENTS MAP 4 6 COMMERCIAL/MIXED USE CULTURAL 9 GOVERNMENT & NONPROFIT INSTITUTIONS 10 HEALTH CARE & EDUCATION 11 HOSPITALITY 12 PUBLIC SPACE 15 RESIDENTIAL/MIXED USE 18 PROPOSED PROJECTS 29 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 39 CENTER CITY DISTRICT & CENTRAL PHILADELPHIA DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION | CENTERCITYPHILA.ORG | Philly By Drone By | Philly W / Element Hotel W / Element INTRODUCTION Building upon a decade-long, sustained national economic Two large projects east of Broad Street are transforming Phila- expansion, 23 development projects totaling $2.8 billion were delphia’s former department store district. National Real Estate completed in Center City between Fairmount and Washington Development has completed another phase of East Market avenues, river to river, in the period from January 1, 2018 to adding more than 125,000 square feet of retail to their initial August 31, 2019. Eighteen projects totaling $3 billion in new office renovation and construction of two residential towers. A investment were under construction as of September 1, 2019. hotel in the historic Stephen Girard Building is currently under Another 21 projects with a total estimated development value of construction, while work is getting started on the final Chest- $1 billion are in the planning or proposal phase. nut Street phase of this full-block redevelopment. One block to the east, The Fashion District is opening in phases throughout The biggest of the completed projects is the largest develop- the fall of 2019, offering nearly 1 million square feet of shops, ment in Philadelphia’s history: the Comcast Technology Center, restaurants and a multiplex movie theater, designed to connect home to the Four Seasons Hotel, two restaurants, two local directly with public transit while animating both Market and broadcasting networks, an innovation hub and 4,000 Comcast Filbert streets. -

Skyscrapers and the Skyline: Manhattan, 18952004

2010 V38 3: pp. 567–597 DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6229.2010.00277.x REAL ESTATE ECONOMICS Skyscrapers and the Skyline: Manhattan, 1895–2004 Jason Barr∗ This article investigates the market for skyscrapers in Manhattan from 1895 to 2004. Clark and Kingston (1930) have argued that extreme height is a result of profit maximization, while Helsley and Strange (2008) posit that skyscraper height can be caused, in part, by strategic interaction among builders. I provide a model for the market for building height and the number of completions, which are functions of the market fundamentals and the desire of builders to stand out in the skyline. I test this model using time series data. I find that skyscraper completions and average heights over the 20th century are consistent with profit maximization; the desire to add extra height to stand out does not appear to be a systematic determinant of building height. Skyscrapers have captured the public imagination since the first one was com- pleted in Chicago in the mid-1880s. Soon thereafter Manhattan skyscrapers became the key symbol of New York’s economic might. Although the exis- tence and development of skyscrapers and the skyline are inherently economic phenomena, surprisingly little work has been done to investigate the factors that have determined this skyline. In Manhattan, since 1894, there have been five major skyscraper building cycles, where I define a “skyscraper” as a building that is 100 m or taller.1 The average duration of the first four cycles has been about 26 years, with the average heights of completed skyscrapers varying accordingly. -

Manhattan Office Market

Manhattan Offi ce Market 1 ST QUARTER 2016 REPORT A NEWS RECAP AND MARKET SNAPSHOT Pictured: 915 Broadway Looking Ahead Finance Department’s Tentative Assessment Roll Takes High Retail Rents into Account Consumers are not the only ones attracted by the luxury offerings along the city’s prime 5th Avenue retail corridor between 48th and 59th Streets where activity has raised retail rents. The city’s Department of Finance is getting in on the action, prompting the agency to increase tax assessments on some of the high-profi le properties. A tentative tax roll released last month for the 2016-2017 tax year brings the total market value of New York City’s real estate to over $1 trillion — reportedly for the fi rst time. The overall taxable assessed values for the city would increase 8.10%. Brooklyn’s assessed values accounted for the sharpest rise of 9.83% from FY 2015/2016, followed by Manhattan’s 8.47% increase. Although some properties along the 5th Avenue corridor had a reduction in valuations the properties were primarily offi ce, not retail according to a reported analysis of the tentative tax roll details. Building owners have the opportunity to appeal the increase; but an unexpected rise in market value — and hence real estate taxes, will negatively impact the building’s bottom line and value. Typically tenants incur the burden of most of the tax increases from the time the lease is signed, and the landlord pays the taxes that existed before the signing; but in some cases the tenant increase in capped, leaving the burden of the additional expense on the landlord. -

Wilmington Downtown, Inc. 910.763.7349

Development Overview – January 2017 Large Development Projects Open, Underway or Announced #10 Since 2014 #1 Courtyard by Marriott #9 #2 CityBlock Apartments #7 #3 Community College Fine Arts Center #4 101 North Third Office Building #5 County Administration Building #13 #3 #2 #6 21 S. Front (NextGlass anchor tenant) #17 #7 Riverwalk Extension #14 #19 #8 Farmin’ on Front Grocery #16 #9 North Waterfront Park #20 #18 #10 Sawmill Point Apartments #11 Riverfront Park Repair #12 #12 Hampton Inn Hotel #15 #1 #13 Port City Marina & Restaurants #8 #4 #5 #14 Embassy Suites Hotel #11 #15 Riverplace (Water St. Deck Redevelop) #6 #16 Multi-Modal Center (Phase 1) #17 Pier 33 Apartments #18 aLoft Hotel #19 Edward Teach Brewery #20 Conlon Pier $371,749,650+ Current Development Projects (#1) Courtyard Marriott Opened Feb. 2014 120Courtyard rooms/$14m by Marriott Current Development Projects (#2) City Block Apartments 112 units/$12m Opened Feb. 2015 Current Development Projects (#3) Cape Fear Comm. College Wilson Fine Arts Center 1,500 seats/$36m Opened October 2015 Current Development Projects (#4) 101 North Third 70,000 sq.ft/$10m Opened October 2015 Current Development Projects (#5) County Admin Bldg. 60,000 sq.ft rehab $7.8m Opened Dec. 2015 Current Development Project (#6) 21 S. Front New NextGlass anchor tenant Condos $1 million (est.) Opened January 2016 Current Development Projects (#7) Riverwalk Expansion $550k Partial Open May 2015 Full Open Fall 2016 Current Development Projects (#9) Farmin’ on Front (Grocery) Budget unannounced Opened Nov. 2016 Current Development Projects (#8) North Waterfront Park Temp. Park Open 2015 $20m approved budget Final Open 2020 Current Development Projects (#10) Sawmill Apartment Under construction 278 units/$48m Opening 1st Qtr. -

Bosque Bello Cemetery Master Plan

Bosque Bello Cemetery Master Plan 2015 City of Fernandina Beach Planning Department Parks and Recreation Department 10/1/2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction/Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………2 General Cemetery Information…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Cemetery History…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………31 Cultural Landscape Information…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..40 Burial Options and Alternatives…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..47 Public Outreach…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..54 Recommendations and Implementation…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….58 Appendices………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….61 THANKS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cemetery Plan Working Group Members: Nan Voit and Meredith Jewell (City Parks Department), Susan Steger, Suanne Thamm, Teen Peterson (Museum of History), Marilyn Barger, Chris Belcher, Marie Santry (Amelia Island Genealogical Society), and Ron Noble (Noble Monument Company). Without the assistance of the working group, this plan would not have been possible. They all contributed many hours and much work to this project. Thank you for your commitment to Bosque Bello. City Clerk’s Office: Mary Mercer, Kim Briley, Caroline Best, Lillie Russell, Cathy Sabattini Amelia Island Museum of History: Phyllis Davis Erin Minnigan, University of Florida Graduate Planning Student Belinda Nettles, University of Florida Ph.D. Planning Student Florida -

The Role of Tall Buildings in Sustainable Cities

The Sustainable City V 345 The role of tall buildings in sustainable cities M. M. Ali School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA Abstract Tall buildings make up the urban fabric and cannot be viewed in isolation from the city. They also bring up ethical, social, and cultural issues, and they impact the local community – their social needs and what the neighborhoods can gain from creating a new tall building. As with the buildings themselves, the urban context in which tall buildings have evolved has changed dramatically since their Chicago origins, reflecting both social and technological developments. A tall building has been variously called a “city within a city,” “a vertical city,” and a “city in the sky.” Thus it is apparent that a tall building is a microcosm of a large city. It is an integral part of the urban habitat having a close relationship with it. In a way it is a vertical progression of a horizontal city. The two are interactive and connected by the transportation, power grid, water supply, and waste production and disposal systems. The tall building can therefore play a vital role in defining livable and sustainable cities. Both cities and skyscrapers must use fewer natural resources; create less waste; and impact less on the natural world. Technology will continue to improve the physical systems of the skyscraper and the city; however, their future will be defined by human interests and values. Keywords: sustainable development, tall building, city as ecosystem, skylines, megacities. 1 Introduction It is projected that by 2030, 5 billion people will live in urban areas throughout the world [1]. -

Cape Fear Commercial 1051 Military Cutoff Rd | Suite 200 Wilmington, NC 28405 (P) 910.344.1000 (F) 910.344.1020 River Place PROPERTY OVERVIEW Wilmington, NC

Presented By: Cape Fear Commercial 1051 Military Cutoff Rd | Suite 200 Wilmington, NC 28405 (p) 910.344.1000 (f) 910.344.1020 River Place PROPERTY OVERVIEW Wilmington, NC ADDRESS: Water Street Wilmington, North Carolina New Hanover County AVAILABLE SF: 1,180 SF - 10,560 ASKING RATE: $29.50 PSF NNN / estimated $5.00 PSF TICAM $40 PSF TI Allowance DELIVERY DATE: LEASE RATE Approximately January 2020 DESCRIPTION: River Place is a 13-story mixed-use development featuring 32,000 SF Retail Space, 92 Luxury For-Sale Condominiums, 79 Luxury Rental Apartments and 403 Public/Leased Parking Spaces . Currently +/- 65% of the condominiums have been presold and 45% of the commercial space has been preleased! A landmark project for Wilmington, NC, River Place will be the first modern mixed use development of its kind in its Downtown neighborhood. For more information, please contact: Patrick Riley 910.344.1018(direct) 910.264.2153 (mobile) [email protected] capefearcommercial.com River Place FIRST FLOOR: 1,180 -10,560 SF Wilmington, NC LEASE PENDING RETAIL/ RESTAURANT 2,457 SF RETAIL RETAIL RETAIL RETAIL RETAIL RETAIL RETAIL 1,180 SF 1,248 1,371 1,371 1,371 1,371 1,371 SF SF SF SF SF SF FEATURES: Patio Space Can be subdivided Designated Restaurant Space available with grease trap and ventilation For more information, please contact: Patrick Riley 910.344.1018(direct) 910.264.2153 (mobile) [email protected] capefearcommercial.com River Place THIRD FLOOR: 1,826 SF Wilmington, NC 1,826 SF AVAILABLE FEATURES: Patio Space Connectivity -

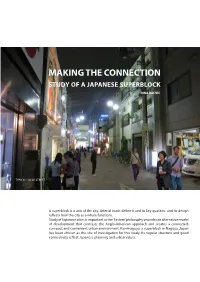

Making the Connection: Study of a Japanese Superblock

MAKING THE CONNECTION STUDY OF A JAPANESE SUPERBLOCK DINA BACVIC TYPICAL LOCAL STREET A superblock is a unit of the city. Arterial roads define it and its key qualities, and its design reflects how the city as a whole functions. Study of Japanese cities is important as the ‘Eastern’ philosophy provides an alternative model of development that contrasts the Anglo-American approach and creates a connected, compact and convenient urban environment. Kaminagoya, a superblock in Nagoya, Japan has been chosen as the site of investigation for this study. Its regular structure and good connectivity reflect Japanese planning and urban values. HISTORY The examples of superblock models examined here are from Anglo-American culture, and until 1980s each displayed the characteristics of ever increasing disconnect between the interior and exterior of the superbock. In 1980, New Urbanism presented an alternative to the prevalent philosophy. However, the concept was still embedded within the typically radial western city structure. These precedents are presented in contrast to the Japanese superblock, exemplified by Kaminagoya. KAMINAGOYA AERIAL VIEW KAMINAGOYA ROAD NETWORK AND USE VISUALISATION 200m 1929 - Perry’s model The concept of a neighbourhood unit as a distinct residential area was advocated by Clarence Perry in 1929. He designed the model for a ‘family-life community’ with a desire to create a wholesome society. The underlying principle of the design was that a neighbourhood would be a distinct entity, which would be connected to other neighbourhood units via an arterial road system. The size of the neighbourhood unit was based on a 400m walking radius and the density required was that which would support a centrally located elementary school. -

Urban Design Concepts

Urban Design Concepts 6th St. – Wetmore Recommendations, Urban Form Analysis, & Prototype Developments Recommendations Require design that (a) reinforces urban Seek opportunities to celebrate the history of character, including densities that provide Stone Avenue through preservation and creative sufficient1 population to support increased alternative use3 of older buildings, unusual signage, and other transportation use and a greater mix of commercial distinctive elements within the corridor. and retail uses, and (b) promotes urban form that allows easy access to adjacent land uses by Incorporate individual pieces of public art and pedestrians and clear visibility of the uses for all 4 artistic treatment of functional elements, such passers-by. Design proposals for properties adjacent as pavement, into both public and private projects. to Stone Avenue should demonstrate sensitivity to Where appropriate, use artistic treatments to help nearby neighborhoods. strengthen the identities of the neighborhoods. Focus on vacant lots and underutilized properties to fill in gaps along the corridor (i.e., infill2 development) with the objective of stabilizing land uses and encouraging economic development where needed most. Urban Form Analysis Stone Avenue is an urban corridor made up of varied land uses, block types and sizes, and multiple parcel arrangements and sizes. The urban form analysis helps in understanding the corridor’s constituent parts and the corridor as a whole. The analysis process is introduced in the diagram below and further elaborated in the following pages. 1 Street Grid 2 Analysis 3 Block Plan This shows the corridor made This is a process of looking at urban This shows the corridor made up of up of streets, as commonly form (e.g., street grid) & representing blocks that reflect the scale of the shown on street maps, & serves it in a different way that shows city as it changes over the length of to direct people to places.