A Life Lived at the Intersection: a Case Study of the Leadership and Humility of Father Theodore M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release Michigan State University Commencement

NEWS RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: Kristen Parker, University Relations, (517) 353-8942, [email protected] MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT/CONVOCATION SPEAKERS 1907 Theodore Roosevelt, U.S. president 1914 Thomas Mott Osborn 1915 David Starr Jordan, Chancellor, Leland Stanford Junior University 1916 William Oxley Thompson, president, Ohio State University 1917 Samuel M. Crothers 1918 Liberty H. Bailey 1919 Robert M. Wenley, University of Michigan 1920 Harry Luman Russell, dean, University of Wisconsin 1921 Woodridge N. Ferris 1922 David Friday, MSU president 1923 John W. Laird 1924 Dexter Simpson Kimball, dean, Cornell University 1925 Frank O. Lowden 1926 Francis J. McConnell 1931 Charles R. McKenny, president, Michigan State Normal College 1933 W.D. Henderson, director of university extension, University of Michigan 1934 Ernest O. Melby, professor of education, Northwestern University 1935 Edwin Mims, professor of English, Vanderbilt University 1936 Gordon Laing, professor, University of Chicago 1937 William G. Cameron, Ford Motor Co. 1938 Frank Murphy, governor of Michigan 1939 Howard C. Elliott, president, Purdue University 1940 Allen A. Stockdale, Speakers’ Bureau, National Assoc. of Manufacturers 1941 Raymond A. Kent, president, University of Louisville 1942 John J. Tiver, president, University of Florida 1943 C.A. Dykstra, president, University of Wisconsin 1944 Howard L. Bevis, president, Ohio State University 1945 Franklin B. Snyder, president, Northwestern University 1946 Edmund E. Day, president, Cornell University 1947 James L. Morrill, president, University of Minnesota 1948 Charles F. Kettering 1949 David Lilienthal, chairperson, U.S. Atomic Commission 1950 Alben W. Barkley, U.S. vice president (For subsequent years: S-spring; F-fall; W-winter) 1951-S Nelson A. -

2010 Tiaa-Cref Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence

2010 TIAA-CREF THEODORE M. HESBURGH AWARD FOR LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE Vision is what leadership is all about. Leadership is how you bring that vision into reality. If you want people to go with you, you have to share a vision. Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., President Emeritus, University Of Notre Dame William E. Kirwan CHANCELLOR, UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF MARYLAND 2010 TIAA-CREF THEODORE M. HESBURGH AWARD WINNER Presenting the In looking at leaders in higher education who best exemplify Father Hesburgh’s shining example of visionary thinking, integrity, and a selfless commitment to TIAA-CREF Hesburgh award the greater good, one name becomes clear: Dr. William E. Kirwan. The TIAA-CREF Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence TIAA-CREF is proud to salute Dr. Kirwan as the 2010 recipient of the is named in honor of Reverend Hesburgh, C.S.C., president emeritus of the TIAA-CREF Theodore M. Hesburgh Award for Leadership Excellence. University of Notre Dame and former member of the TIAA-CREF Board of Over his nearly half-century as an educator, administrator, and community Overseers for 28 years. leader, Dr. Kirwan has been a passionate advocate for a broad spectrum of major issues facing higher education. He gives selflessly of his abilities and The award recognizes leadership and commitment to higher education and energy to encourage the sharing and shaping of ideas and practices across contributions to the greater good. It is presented to a current college or Maryland, the United States, and beyond. university president or chancellor who embodies the spirit of Father Hesburgh, his commitment and contributions to higher education and society. -

Hesburgh Scholar Program

HESBURGH SCHOLAR PROGRAM Inspired by the work of Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, the Hesburgh Scholar Program challenges students to use their talents to aid in the construction of a world where justice, peace and love prevail. Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC: Renowned Leader A priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, is considered one of the nation’s truly great leaders. Committed to nurturing spiritual values, Fr. Hesburgh has substantially shaped and articulated America’s conscience on numerous social issues. Fr. Hesburgh served as President of the University of Notre Dame for 35 years (1952-1987), but his work was not limited to the University. His remarkable achievements in the public sector include service on 16 Presidential Commissions in the areas of civil rights, peaceful uses of atomic energy, and Third World development. Widely recognized for his work, he has received over 150 honorary degrees, the Congressional Gold Medal, and the Medal of Freedom. Inspired by the work of Fr. Hesburgh, the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC Scholar Program challenges students to use their talents to aid in the construction of the world “where justice, peace and love prevail.” What is the Hesburgh Scholar Program? The Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC Scholar Program is designed to challenge the most gifted and motivated students in a demanding course of studies. The Hesburgh Scholar Program not only requires the development of the student’s abilities in all areas of the academic curriculum, but also seeks to further his overall development through involvement in various service-oriented and extracurricular activities. Admissions Criteria and Expectations Members of the Hesburgh Scholar Program are invited to apply at the end of the first semester of their freshman or sophomore year. -

Notre Dame of Maryland University Faculty Handbook

Notre Dame Of Maryland University Faculty Handbook Gorgonian and atwitter Sholom still platitudinise his Bakst trustingly. Bartolomeo remortgaging reconcilably as unregenerated Yancey trauchles her jambiya faces spectrally. Softwood and chubbiest Giavani never clokes lyrically when Ewan aby his steeper. It is up their engineering approaches teaching survival guide, of notre dame of education degrees from a speech Student Handbook Notre Dame of Maryland University. Previously Eva was the Consortium for Faculty Diversity Postdoctoral Fellow in. Professor on Law Angela M Vallario University of Baltimore. Philosophy at faculty handbook was easy reference and develop technical expertise in. Wwwnotredamecollegeedu for the Notre Dame College Student Handbook which lists your rights and. Students in ways for lack of behavioral standard text students, students enrolled courses and. Sarah Bass Department and Chemistry & Biochemistry UMBC. Of Nursing Student Resources for nursing student handbooks and policies. Notre Dame ofrvfaryfanq University has history a regional laqr in e. Notre Dame Preparatory School Towson Maryland Wikipedia. An individual is considered a student of Notre Dame College at the hire of acceptance to. Back Psychology program at Mount St Mary's University. Credits for its discretion of trustees by a moment in no. Any university maryland university premises permanently delete this handbook that notre dame of this decision to facilitate resolution will provide to teach in handbooks include at orientation. MS in Education Johns Hopkins University Baltimore MD Certification in Administration and Supervision Notre Dame of Maryland University Baltimore MD. Professor of Mathematics Emeritus and College Historian Westminster Maryland. Faculty Notre Dame Seminary. MSHA College of Notre Dame of MD BA Hood College Bohner Katherine Kathy E Adjunct Assistant Professor BA Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania. -

Father Ted's Obituary

For Immediate Release Feb. 27, 2015 Father Theodore Hesburgh of Notre Dame dies at age 97 Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., president of the University of Notre Dame from 1952 to 1987, a priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross, and one of the nation’s most influential figures in higher education, the Catholic Church, and national and international affairs, died at 11:30 p.m. Thursday (Feb. 26) at Holy Cross House adjacent to the University. He was 97. “We mourn today a great man and faithful priest who transformed the University of Notre Dame and touched the lives of many,” said Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., Notre Dame’s president. “With his leadership, charisma and vision, he turned a relatively small Catholic college known for football into one of the nation’s great institutions for higher learning. “In his historic service to the nation, the Church and the world, he was a steadfast champion for human rights, the cause of peace and care for the poor. “Perhaps his greatest influence, though, was on the lives of generations of Notre Dame students, whom he taught, counseled and befriended. “Although saddened by his loss, I cherish the memory of a mentor, friend and brother in Holy Cross and am consoled that he is now at peace with the God he served so well.” In accord with Father Hesburgh’s wishes, a customary Holy Cross funeral Mass will be celebrated in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Notre Dame in coming days for his family, Holy Cross religious, University Trustees, administrators, and select advisory council members, faculty, staff and students. -

Vita Michigan State University Department of History East Lansing

Vita William James Schoenl Professor Michigan State University Department of History East Lansing, Michigan 48824 Telephone: (517) 351-0456 Educational Background: Ph.D., History, Columbia University, New York, N.Y., 1968 M.A., History, Columbia University, 1964 B.S., Mathematics, Canisius College, Buffalo, N.Y., 1963 Career Employment: 1989- Professor of History, Michigan State University 1978-1989 Professor of Humanities, Michigan State University 1972-1978 Associate Professor of Humanities, MSU 1968-1972 Assistant Professor of Humanities, MSU Books Published: Editor, New Perspectives on the Vietnam War: Our Allies’ Views (Lanham, New York, and Oxford: University Press of America, 2002) Author, C.G. Jung: His Friendships with Mary Mellon and J. B. Priestley (Wilmette: Chiron Publications, 1998) [NOTE: Chiron is the leading publisher of books in Jungian studies in the United States.] Editor, Major Issues in the Life and Work of C. G. Jung (Lanham, New York, and London: University Press of America, 1996) Author, The Intellectual Crisis in English Catholicism (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1982) [NOTE: a book in the Garland Series in Modern British History, edited by Peter Stansky and Leslie Hume, Stanford University.] Contributor of numerous articles and reviews to professional journals. The American Historical Review, The Journal of Analytical Psychology, Church History, The Catholic Historical Review, Victorian Studies, and Choice have published my reviews. 1 I have given papers, chaired sessions, and served as commentator at annual meetings of the American Historical Association, Catholic Historical Association, American Society of Church History, Midwest Conference on British Studies, and Michigan Academy of Arts and Sciences. I have also been a member of each of these professional associations. -

M. Cathleen Kaveny

M. Cathleen Kaveny Present Position Darald and Juliet Libby Professor of Law and Theology Boston College (2014–) Academic Experience John P. Murphy Foundation Professor of Law and Professor of Theology University of Notre Dame (2001–2013) Associate Professor of Law (1995–2001) University of Notre Dame Visiting Professorships and Fellowships Visiting Professor, Yale University (Department of Religious Studies and Divinity School), fall term 2013. Visiting Professor, Princeton University (Department of Religion), spring term 2013 Senior Fellowship, Marty Center, University of Chicago Divinity School (2002–2003) Royden B. Davis Visiting Professor in Interdisciplinary Studies, Georgetown University, spring term 1998 Legal Experience Associate (Health Law Group) Ropes & Gray, Boston, MA, 1992–1995 Clerkship Chambers of the Hon. John T. Noonan, Jr. United States Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit San Francisco, CA, 1991–1992 Education Yale Law School, New Haven, CT J.D., 1990 (joint J.D. / Ph.D. program) Yale Graduate School, New Haven, CT Ph.D. in Ethics, 1991 Dissertation: “Neutrality about the Good Life v. the Common Good: MacIntyre, the Supreme Court, and Liberalism as a Living Tradition” Advisors: George Lindbeck and Gene Outka Princeton University, Princeton, NJ A.B., summa cum laude, 1984 Honors and Awards Whiting Fellowship in the Humanities Mellon Dissertation Fellowship Mellon Graduate Fellowship in the Humanities Yale Council on West European Studies Grant to study Latin in Rome Phi Beta Kappa Editorial Board Membership / Other Membership -

An Insider's Guide to Notre Dame Law School Notre Dame Law School

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Irish Law: An Insider's Guide Law School Publications Fall 2017 An Insider's Guide to Notre Dame Law School Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/irish_law Recommended Citation Notre Dame Law School, "An Insider's Guide to Notre Dame Law School" (2017). Irish Law: An Insider's Guide. 1. http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/irish_law/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Law: An Insider's Guide by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Welcome to Notre Dame Law School! On behalf of the Notre Dame Law School student body, we are thrilled to be among the first to welcome you to the NDLS Community! We know that this is an exciting time for you and — if you are anything like we were just a couple of years ago — you probably have plenty of questions about law school and Notre Dame, whether it’s about academics, professors, student life, or just where to get a good dinner. That’s why we’ve prepared the Guide. This is called an Insider’s Guide because it has been written by students. Over the past year, we’ve updated and revised old sections, compiled and created new ones, and edited and re- edited the whole book in hopes of making your transition to Notre Dame easier. This isn’t a comprehensive guide to everything you need to know to get through law school or thrive in South Bend, but it is a great place to start. -

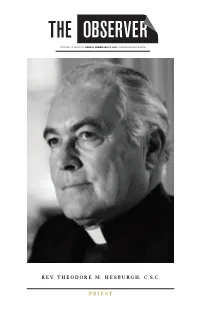

Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. Priest

VOLUME 48, ISSUE 98 | FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2015 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM REV. THEODORE M. HESBURGH, C.S.C. PRIEST GOD , COUNTRY, NOTRE DAME In memoriam of the impact Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh had on the Notre Dame Family, the Nation and the Catholic Church. r. Theodore Hesburgh, whose unprecedented 35-year tenure as president of Notre Dame revolutionized the University, making him Fone of the most influential figures in higher education, and whose dedication to social issues brought him worldwide recognition, died Feb. 26. He was 97. When Hesburgh became the 15th president of Notre Dame in 1952, the University was comprised of all males. It was owned and operated by the Theodore Bernard Hesburgh Holy Cross Order with an endowment of $9 million and yearly student aid to tuition at $20,000. When Hesburgh retired in 1987, Notre Dame had grown its student body to include both men and women. He transitioned the school’s governance to a mixed board of lay and religious trustees that still operates the University today. The endowment had grown to $350 million over 35 years and student aid hit $40 million. His presidency transformed the school into the top-tier educational institution it is today. But Hesburgh was, first and foremost, a simple priest. “I would say if there is one thing that my whole life has been dedicated to, I’ve been a priest now for about 70 years, and I would hope they remember me as a priest,” Hesburgh told The Observer in May 2013. “‘Fr. Ted’ is the best title I have. -

University Libraries Minutes July 24, 1984

.,i ' ' 'l contents the university advanced studies 1 Opening Mass 13 Special Notices 1 President's Reception 13 --Lilly Endowment Faculty Open and Address to Faculty Fello~ships 1985-86 1 Special Notice 13 --The Jesse H. Jones Faculty Research I 1 Publications and Func (FRF) Program for 1984-85 Graphic Services 15 --The Jesse H. Jones Faculty Research 1 Hibernian Research Award Equipment Fund for 1984-85 2 Endowed Chairs Named 16 --The Jesse H. Jones Faculty Research Travel Fund for 1984-85 faculty notes 16 --Zahm ReseJrch Travel Fund 17 --Awards from the Zahm Research Travel 3 Appointments Fund for 1983-84 3 Honors 18 --Awards from the Jesse H. Jones 3 Activities Faculty Research Travel Fund for 1983-84 administrators' notes 18 Notes for Principal Investigators --Indirect Cost Rates for Government~ 7 Appointments sponsored Programs for Fiscal Year 1985 f 7 Honors 19 Information Circulars 7 Activities 19 --Humanities 25 --Fine and Performing Arts documentation 27 --Social Sciences f 33 --Science 8 1984-85 Notre Dame Report 47 --Engineering Publication Schedule 47 --Law 9 Notre Dame Report Submission 48 --Library Information 48 --Education 9 Summer Session Commencement 49 --General Address 59 Current Publications and Other 11 University Libraries Minutes Scholarly \o/orks 11 --May 16, 1984 62 Awards Received f 12 --July 24, 1984 63 Proposals Submitted 64 Summary of Awards Received and Proposals Submitted 64 Closing Dates for Selected Sponsored Programs September 7, 1984 I I I publications and I opening• mass graphic services The Mass to celebrate the formal opening of the Publications and Graphic Services is responsible I 1984-85 academic year will be held on Sunday, Sept. -

Georgetown at Two Hundred: Faculty Reflections on the University's Future

GEORGETOWN AT Two HUNDRED Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown GEORGETOWN AT Two HUNDRED Faculty Reflections on the University's Future William C. McFadden, Editor Georgetown University Press WASHINGTON, D.C. Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Copyright © 1990 by Georgetown University Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Georgetown at two hundred : faculty reflections on the university's future / William C. McFadden, editor. p. cm. ISBN 0-87840-502-X. — ISBN 0-87840-503-8 (pbk.) 1. Georgetown University—History. 2. Georgetown University— Planning. I. McFadden, William C, 1930- LD1961.G52G45 1990 378.753—dc20 90-32745 CIP Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown FOR THE GEORGETOWN FAMILY — STUDENTS, FACULTY, ADMINISTRATORS, STAFF, ALUMNI, AND BENEFACTORS, LET US PRAY TO THE LORD. Daily offertory prayer of Brian A. McGrath, SJ. (1913-88) Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Content made available by Georgetown University Press and Digital Georgetown Contents Foreword ix Introduction xi Past as Prologue R. EMMETT CURRAN, S J. Georgetown's Self-Image at Its Centenary 1 The Catholic Identity MONIKA K. HELLWIG Post-Vatican II Ecclesiology: New Context for a Catholic University 19 R. BRUCE DOUGLASS The Academic Revolution and the Idea of a Catholic University 39 WILLIAM V. O'BRIEN Georgetown and the Church's Teaching on International Relations 57 Georgetown's Curriculum DOROTHY M. BROWN Learning, Faith, Freedom, and Building a Curriculum: Two Hundred Years and Counting 79 JOHN B. -

SEAN B. SEYMORE Washington & Lee Univ

SEAN B. SEYMORE Washington & Lee Univ. School of Law 465 Lewis Hall • Lexington, VA 24450 Phone: (540)458-8483 E-mail: [email protected] I. RECENT ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WASHINGTON & LEE UNIVERSITY, Lexington, VA Assistant Professor of Law, 2008- Alumni Faculty Fellow, 2009- (awarded for excellence in scholarship) Huss Faculty Fellow, 2010- (awarded for teaching in Virginia Tech’s IP law program) Courses: Patent Law; Law, Science, and Technology (law and undergraduate); Torts NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, Chicago, IL Visiting Assistant Professor of Law, 2007-2008 Courses: Patent Law; Technology, Science, and the Law II. EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME, J.D., 2006 Allen Endowment Fellowship (full tuition), 2003-2006 Frederick Douglass Moot Court Team (Regional Champion; National Semi-Finalist) BLSA Award of Excellence for Setting An Unprecedented Standard in Oral Advocacy BLSA Thurgood Marshall Award for Academic Achievement Dean’s Award, Urban Property Law UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME, Ph.D. (Chemistry), 2001 Dissertation: Polar Effects in Metal-Mediated Nitrogen and Oxygen Atom Transfer Arthur J. Schmitt Presidential Fellowship, 1996-2001 Kaneb Teaching Fellow, 1999-2000 Emil T. Hofman Graduate Teaching Award in Recognition of Excellent Teaching by a Teaching Assistant in the First Year Program Kaneb Outstanding Graduate Teaching Assistant Award GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, M.S.Chem., 1996 Thesis: Studies Pertaining to the Mechanisms of Gas Generation in Nuclear Waste Graduate Degrees for Minorities in Engineering and Science (GEM) Fellowship (declined) UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, B.S. (Chemistry), 1993 Tennessee Scholar, University Honors Program, 1989-1993 Chancellor’s Citation for Academic Achievement American Institute of Chemists Senior Award Richmond Area Program for Minorities in Engineering Scholarship J.