Christensen Final Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Way Out: the Friendship of Charity As a Countercultural

The Human Way Out 39 in the sad and tragic cycles of family breakdown, and in the owin number of pe~ple who seem to be expendable. Is it any wonde~ eo 1! today are los~ng he'.""t? Are we surprised that the modern m~adfes of the soul with which we struggle are apathy a dan · · , gerous sense of The Human Way Out: res1gn;hon a~d defeat, cynicism, and sometimes even hopelessness? The Friendship of Charity ver thirty years ago in one of The Cold War Letters Thomas M . ton ~p~ke of "the human way out. "1 In confronting th~ fatal patte:~ as a Countercultural Practice of ~1~ h~e, ~erton searched for a more truthful and ho eful wa f env1S10rung life. He decried the "sicke · inh . p Y 0 h · rung umaruties that are every- w ere m the world" and refused to be complacent before them· "Th Paul J. Wadell, C.P. are too awful for human protest to be m . ful . ey to think I . eanmg ,-or so people seem . ~rotest anyway, I am still primitive enough, I have not cau ht ~ with t~1s century. "2 In another of The Cold War Letters writteng at God has a dream for the world, and God's dream is real and ~:V hy~~s :962, Merton wrote poignantly of an hour of crisis before beautiful. God's dream is for absolutely everyone of us to grow to full ;bl1c t f shans, and all people of good will, must do everything pos- ness of life and well-being through justice, compassion, and love. -

George Gebhardt Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

George Gebhardt 电影 串行 (大全) The Dishonored https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-dishonored-medal-3823055/actors Medal A Rural Elopement https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-rural-elopement-925215/actors The Fascinating https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-fascinating-mrs.-francis-3203424/actors Mrs. Francis Mr. Jones at the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mr.-jones-at-the-ball-3327168/actors Ball A Woman's Way https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-woman%27s-way-3221137/actors For Love of Gold https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/for-love-of-gold-3400439/actors The Sacrifice https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-sacrifice-3522582/actors The Honor of https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-honor-of-thieves-3521294/actors Thieves The Greaser's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-greaser%27s-gauntlet-3521123/actors Gauntlet The Tavern https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-tavern-keeper%27s-daughter-1756994/actors Keeper's Daughter The Stolen Jewels https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-stolen-jewels-3231041/actors Love Finds a Way https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/love-finds-a-way-3264157/actors An Awful Moment https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/an-awful-moment-2844877/actors The Unknown https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-unknown-3989786/actors The Fatal Hour https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-fatal-hour-961681/actors The Curtain Pole https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-curtain-pole-1983212/actors -

Returning in the Gloaming Courtesy Chicago Art Institute 2 the BAPTIST HERALD August 1

The Baptist Herald A DENOMINATIONAL PAPER VOICING THE INTERESTS OF THE GERMAN BAPTIST YOUNG PEOPLE'S AND SUNDAY SCHOOL WORKERS' UNION Volume Eight CLEVELAND, 0., AUGUST 1, 1930 Number Fifteen Returning in the Gloaming Courtesy Chicago Art Institute 2 THE BAPTIST HERALD August 1. 1930 3 What's .Happening Rev. Thos. Stoeri, pastor of the St. J oseph congregation for the fin e concert The Annual Meeting of the B. Y. Louis P ark Baptist Church, St. Louis, which was outstanding by a program of P. U. of the First Church, Baptist Herald interesting variety. There were four The Mo., had the joy of baptizing three adults early in July. All were married ladies, choir s which sang singly and in unison, a Portland, Oreg. two of them .an elderly mother and her stringed orchestr a, duets, quartets, reci Another year has passed, and never Singing his own disciples "friends" (John 15 :14), if they daughter. tations and a solo on a musical saw. before had we had such a r ar e oppor would do whatsoever he commanded them to do. tunity of par taking of a " Hot Baked Sing when the sun is shining; Rev. Albert Alf, pastor of the German Dr. Herbert Grimmell Pfeiffer, son of H am" dinner, served in the church base And Abraham had the distinction to be called the Rev. Jacob Pfeiffer, graduate of Baylor town, N . Dak., church, r esigned after a ment June 5, at 6.30 P. M. Sing when the shadows fall; pastorate of somewhat over four years, University, Dallas, Texas, in 1929, has • "friend of God." There is in the Old Testament After r elishing the tasty "baked ham" Sing, and set others singing; the most beautiful example of friendship in the story to accept the pastorate of t he church at just completed a successful year's intern dinner, and enjoying a happy social hour, That is the best of all. -

1925 Virginian State Teacher's College

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Yearbooks Library, Special Collections, and Archives 1-1-1925 1925 Virginian State Teacher's College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/yearbooks Recommended Citation State Teacher's College, "1925 Virginian" (1925). Yearbooks. 69. http://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/yearbooks/69 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library, Special Collections, and Archives at Digital Commons @ Longwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yearbooks by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Longwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/virginian1925stat OiiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiMiiiiiiiniiiiiiiMiiiaiiiniiiiiiitiiiiiiMMiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiic ITbe IDlrgintaU".mniiiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiJiiriEiiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiJciiiiiiiiiMiiDiiiiiMiiif^i ae V iFgiman i imeteeia JniuiidLired and 1 weml dliiedl Iky the Oiu.aen.i RoAj of tike oiate 1 eacJkers C^ollege Jr ariMLville, Virginia 'iniXKi >niii iiniiiiitiiEii iniiaiiiiuiiiiiiuiiuiiiiMiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiniNiiiiiiiiiniiuiiiiiiiini iiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiii iiniiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiinin iiiinriiiiiiiiiiiE« >Toiiiiiiiiiiii[]iiiiiiiiiiii[3iiiiuiiimniiiiiiiiiiiic]iiiiiiiiiiiiE}iiiiiiiiiiii[; ^be IDirotntan iiiiciiiiiiiiiiNiHiiiiiiiiiiiitiimiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiitiiiiiiiiiiiiiaiiiiiiiiici DR. J. L. JARMAN Our President -

Catalogue of Stereopticons, Dissolving View Apparatus, Magic Lanterns

+**Ai »^..A^^w^»..»......»»...^».AA«..«t»»t*>A*i CATALOGUE AID PRICE LIST STEREOPTICONS,OF dissolving Views, Apparatus, Magic Zanterns, and Artistically Colored Thotograpliic Views, That eminent Philosopher, Sir David Brewster, says, " Thr. Sfqgte Lantern, which, for a long Hme was us'd only as an ins'rwnent for amusing children, and astonishing the. ignorant, has recently been fitted up for the betUr purpose, of conveying Scientific Instruction, and it is vow univer- sally used by popular Lecturers. It m -y be used in almost every branch where it it desirable to give a distinct and enlarged representation to a large audience." t. h. McAllister, (0» THB 1JATE FlBK OF MCALLISTER <fc BROTHER, PHILADELPHIA.—ESTAB: 179C.) Optician, 49 NASSAU ST., NEW YORK. This Catalogue Is for gratuitous distribution, and sent by Mail free of charge. KCWtN BARTOW, PRINTER, 80 & 82 DUASE ST., NEW YORK. •5 « a M •73 o O . ... «> d. s M B a o © •»« — •>-) a J •-* a as oj 03 b& id 1- " S bo "" g« CO & S oj y © CO a c8 W d V w si © M ©— > BJ"" W K -a »* e. c oj d a a 13 « a u a pq * J?*fc !s a i- °° S o.2 «©© » d ^ h a g o P« H s a o o o V mo '« * oo JS- M CO O « a "3 'a 0Q © s o -f d CQ «© o CS = s a .. o d © © - a H 4-i u J8"S as O a a eg g en 5* ID u CQ S _, a| O « g •wH .S « £> >>bo g » c <^= ? a e 5 CO d 0,a o ^ ^ CO « » d * _j a o ^^ o ^ Sd ut- " m b^ r e o 2 © CO -73 © v .2 °5 a £ u 5 t*> o « a . -

LESS THAN IDEAL? the INTELLECTUAL HISTORY of MALE FRIENDSHIP and ITS ARTICULATION in EARLY MODERN DRAMA By

LESS THAN IDEAL? THE INTELLECTUAL HISTORY OF MALE FRIENDSHIP AND ITS ARTICULATION IN EARLY MODERN DRAMA by WENDY ELLEN TREVOR A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. This thesis examines the intellectual history of male friendship through its articulation in non-Shakespearean early modern drama; and considers how dramatic texts engage with the classical ideals of male friendship. Cicero’s De amicitia provided the theoretical model for perfect friendship for the early modern period; and this thesis argues for the further relevance of early modern translations of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, and in particular, Seneca’s De beneficiis, both of which open up meanings of different formulations and practices of friendship. This thesis, then, analyses how dramatists contributed to the discourse of male friendship through representations that expanded the bounds of amity beyond the paradigmatic ‘one soul in two bodies’, into different conceptions of friendship both ideal and otherwise. -

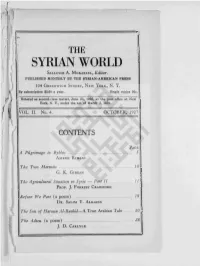

Syrian World Salloum A

f THE SYRIAN WORLD SALLOUM A. MOKARZEL, Editor. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE SYRIAN-AMERICAN PRESS 104 GREENWICH STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y. By subscription $5.00 a year. Single copies 50c, . Entered as second-class matter, June 25, 1926, at the post office at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. VOL. II. No. 4. OCTOBER, 1927 CONTENTS PAGE A Pilgrimage to Byblos 3 AMEEN RIHANI The Tzvo Hermits 10 G. K. GlBRAN The Agricultural Situation in Syria — Part II // PROF. J. FORREST CRAWFORD Before We Part (a poem) 19 DR. SALIM Y. ALKAZIN The Son of Haroun Al-Rashid—A True Arabian Tale 20 The Adieu (a poem) 28 J. D. CARLYLE CONTENTS (Continued) PAGE Famous Cities of Syria — Byblos, City of Adonis 29 "Anna Ascends" — (A Play) — Act Two—II 33 HARRY CHAPMAN FORD Choice Arabian Tales:— Rare Presence of Mind 45 The Test of Friendship 46 Reward and Punishment 47 Notes and Comments—By THE EDITOR Bayard Dodge 48 The End of an Experiment 49 Our Bulwark 49 Readers' Forum 57 Sprit of the Syrian Press 53 About Syria and Syrians 57 Political Developments in Syria 62 ILLUSTRATIONS IN THIS ISSUE Panoramic View of Byblos The Fortress of Byblos Relics of Old Glory in Byblos Astartey Phoenician Goddess of Love and Productivity A City Gate in Byblos Sarcophagus of King Ahiram Two Illustrations of "Anna Ascends" g^- ?*- -, 3?/ THE SYRIAN WORLD assi w m OCTOBER, 1927 1 SYRIAN WORLD VOL. II. No. 4. OCTOBER, 1927 A Pilgrimage to Byblos By AMEEN RIHANI * Let Urashlim and Mecca wait, And China stew in her own juice; This way the 'pilgrim staff, tho late, Of Christian, Mussulman and Druse. -

Download File

Marion Leonard Lived: June 9, 1881 - January 9, 1956 Worked as: film actress, producer, screenwriter Worked In: United States by Sarah Delahousse It is well known that Florence Lawrence, the first “Biograph Girl,” was frustrated in her desire to exploit her fame by the company that did not, in those years, advertise their players’ names. Lawrence is thought to have been made the first motion picture star by an ingenious ploy on the part of IMP, the studio that hired her after she left the Biograph Company. But the emphasis on the “first star” eclipses the number of popular female players who vied for stardom and the publicity gambles they took to achieve it. Eileen Bowser has argued that Lawrence was “tied with” the “Vitagraph Girl,” Florence Turner, for the honorific, “first movie star” (1990, 112). In 1909, the year after Lawrence left Biograph, Marion Leonard replaced her as the “Biograph Girl.” At the end of 1911, Leonard would be part of the trend in which favorite players began to find ways to exploit their popularity, but she went further, establishing the first “star company,” according to Karen Mahar (62). Leonard had joined the Biograph Company in 1908 after leaving the Kalem Company, where she had briefly replaced Gene Gauntier as its leading lady. Her Kalem films no longer exist nor are they included in any published filmography, and few sources touch on her pre-Biograph career. Thus it is difficult to assess her total career. However, Marion Leonard was most likely a talented player as indicated by her rapid ascension to the larger and more prominent studio. -

Arthur Severus O'toole

ARTHUR SEVERUS O'TOOLE. THE O'TOOLES, .ANCIENTLY LORDS OF POWERSCOURT (FERACUALA.N), FERTIRE, AND IMALE; WITH SOME NOTICES OF FEA_GH 1IAO HUGH O'B.YRNE, CHIEF OF CLA.N-RANELAGH. BY J O H N O'T O O L E, E SQ., tu CHIEF OF HIS NAME. Virtute et Fidelita.te. DUBLIN: A. M. SULLIVAN, 90 MIDDLE ABBEY-STREET. DIS. MANIBUS .. TO THE SHADE OF THE REVEREND FATHER F--, S.J., WHlLOl\I l\1Y VENERATED PRECEPTOR IN THE COLLEGE OF CLONGOWES ; .AND TO THAT OF' THE REVEREND FATHER n·--, FORMERLY PASTOR OF THE PARISH OF SAINT MICHAEL, RATHDRUM, IN THE COUNTY OF WICKLOW. I UFFER, DEDICATE, AND CONSECRATE THE FOLLO,\'ING PAGES, J. O'T. PREFACE. EVERY man's life·has its epoch. :Th-line dates from the close of July, 183-, when I completed my academic career in the College of Clongowes. That, indeed, is to n1e a mernorable day, for it terminated the mild restraint to w·hich I had been subject for n1ore than seven years, ancl allowed me to exchange the scene of my childhood and dawning manhood for the ,vide, wide world . .Strange as.it 1nay appear, I was not at all anxious to leave the place, but rather calculated on spending another year there to perfect myself in the Italian, French, and German languages, which I could easily have done by conversing with some of the revere1id Fa,thers, who had passed 1nany years on the Continent, and were familiar with each of these tongues. ''I too," said I to myself, '' will visit Rome and other co1itinental capitals ; but how . -

THE AGE of INNOCENCE by Edith Wharton Book I I. on a January Evening of the Early Seventies, Christine Nilsson Was Singing in Fa

THE AGE OF INNOCENCE By Edith Wharton Book I I. On a January evening of the early seventies, Christine Nilsson was singing in Faust at the Academy of Music in New York. Though there was already talk of the erection, in remote metropolitan distances "above the Forties," of a new Opera House which should compete in costliness and splendour with those of the great European capitals, the world of fashion was still content to reassemble every winter in the shabby red and gold boxes of the sociable old Academy. Conservatives cherished it for being small and inconvenient, and thus keeping out the "new people" whom New York was beginning to dread and yet be drawn to; and the sentimental clung to it for its historic associations, and the musical for its excellent acoustics, always so problematic a quality in halls built for the hearing of music. It was Madame Nilsson's first appearance that winter, and what the daily press had already learned to describe as "an exceptionally brilliant audience" had gathered to hear her, transported through the slippery, snowy streets in private broughams, in the spacious family landau, or in the humbler but more convenient "Brown coupe." To come to the Opera in a Brown coupe was almost as honourable a way of arriving as in one's own carriage; and departure by the same means had the immense advantage of enabling one (with a playful allusion to democratic principles) to scramble into the first Brown conveyance in the line, instead of waiting till the cold-and-gin congested nose of one's own coachman gleamed under the portico of the Academy. -

A History of Spanish Golden Age Drama

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Spanish Literature European Languages and Literatures 1984 A History of Spanish Golden Age Drama Henryk Ziomek University of Georgia Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ziomek, Henryk, "A History of Spanish Golden Age Drama" (1984). Spanish Literature. 21. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_spanish_literature/21 STUDIES IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES: 29 John E. Keller, Editor This page intentionally left blank A History of SPANISH GOLDEN AGE DRAMA Henryk Ziomek THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this book was assisted by a grant from Research Foundation, Inc., of the University of Georgia. Copyright© 1984 by The Umversity Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0024 Library of Congress Cataloging -

1 Jeanie Macpherson May 18, 1888

Jeanie Macpherson May 18, 1888 - August 26, 1946 Also: Jeanie MacPherson Worked as : director, film actress, screenwriter The United States Jeanie Macpherson is best known as Cecil B. DeMille’s screenwriter since she collaborated exclusively with the director-producer from 1915, through the silent era and into the sound era, in a working relationship lasting fifteen years. Like many other women who became established as screenwriters, she began her career as a performer, first as a dancer and then as an actress. [Fig. 1 Jeanie Macpherson, early screen role BYU. WFP-MAC16 ] Her numerous acting screen credits begin in 1908, and nearly thirty of the short films she appeared in for the Biograph Company, most directed by D.W. Griffith, are extant. At Universal Pictures, Macpherson began to write, but due to a fluke she also directed the one film that she wrote there—a one-reel western, The Tarantula (1913), according to a 1916 Photoplay article (95). Although Anthony Slide cannot confirm the success of the film, both he and Charles Higham retell the story that when the film negative was destroyed by accident the actress was asked to reshoot the entire motion picture just as she recalled it since the original director was unavailable (Slide 1977, 60; Higham 1973, 38). [Fig. 2 Jeanie Macpherson d/w/a The Tarantula (1913) AMPAS. WFP-MAC18] There are several versions of how after Jeanie Macpherson, out of work after The Tarantula, was hired by DeMille at the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company. The most elaborate version is from Higham who describes Macpherson’s attempt to get an acting job as involving a series of battles between the two while the director was shooting Rose of the Rancho (1914) (38 – 40).