Inhabiting Modernism: Pernes, Portals, and Yeats's Transitive Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham, Catherine, February 2006, Keep Rejects

Catherine Graham Collection: February 2006, 1. Krans, Horatio Sheafe, William Butler Yeats and the Irish Literary Revival. London: William Heinemann, 1905. 2. Moore, George, Confessions of a Young Man. London and Toronto: William Heinemann, 1935. 3. Meredith, George, A Reading of Life: With Other Poems. Westminster: Archibald Constable, 1901. 4. Synge, J.M., (Robin Skelton ed.), Some Sonnets from “Laura in Death” after the Italian of Frencesco Petrarch. Dolmen Eds. Dublin: Dolmen Press Ltd., 1971. 5. Skelton, Robin (ed.), The Collected Plays of Jack B. Yeats. Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1971. 6. Johnston, Denis, The Brazen Horn: A Non-Book for those, who, in revolt today, could be in command tomorrow. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1976. 7. Skelton, Robin, An Irish Album. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1969. 8. Montague, John, All Legendary Obstacles. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1966. 9. Synge, J.M., My Wallet of Photographs. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1971. 10. Clarke, Austin, Mnemosyne Lay in Dust. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1966. 11. O’Grady, Desmond, The Gododdin. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1977. 12. Bickley, Francis, J.M. Synge and the Irish Dramatic Movement. Toronto: Musson Book Co. 13. Horton, W.T. and W.B. Yeats, A Book of Images. London: Unicorn Press, 1898. 14. Yeats, W.B. (ed.), Beltaine: An Occasional Publication. Nos. 1, 2, 3, 1899-1900. London: Sign of the Unicorn, 1900. 15. Poems and Ballads of Young Ireland, 1888. Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son, 1888. 16. Moore, George, Heloise and Abelard. In two volumes, V.I. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921. 17. Raine, Kathleen, Yeats, The Tarot and the Golden Dawn. -

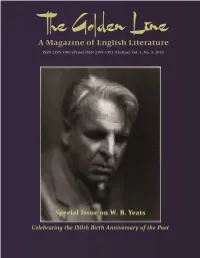

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

WRAP THESIS Robbins 1996.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36344 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Decadence and Sexual Politics in Three Fin-de-Siècle Writers: Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons and Vernon Lee Catherine Ruth Robbins Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick Department of English and Comparative Literature November, 1996 Contents Summary Introduction 1 Chapter One: Traditions of Nineteenth-Century Criticism 17 Chapter Two: Towards a Definition of Decadence 36 Chapter Three: 'Style, not sincerity': Wilde's Early Poems 69 Chapter Four: The Sphinx and The Ballad: Learning the Poetics of Restraint 105 Chapter Five: Arthur Symons — The Decadent Critic as Artist 137 Chapter Six: A Poetics of Decadence: Arthur Symons's bays and Nights and Silhouettes 165 Chapter Seven: 'Telling the Dancer from the Dance': Arthur Symon's London Nights 185 Chapter Eight: Vemon Lee: Decadent Woman? 211 Afterword: 'And upon this body we may press our lips' 240 Bibliography of Works Quoted and Consulted 244 List of Illustrations, bound between pages 136 and 137 Figure 1: 'The Sterner Sex', Punch, 26 November, 1891 Figure 2: 'Our Decadents', Punch, 7 July, 1894 Figure 3: 'Our Decadents', Punch, 27 October, 1894 Figure 4: Edward Bume-Jones, Pygmalion and the Image (1878), nos 1-3 Figure 5: Edward Bume-Jones, Pygmalion and the Image (1878), no. -

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems Compiled by Emma Laybourn 2018 This is a free ebook from www.englishliteratureebooks.com It may be shared or copied for any non-commercial purpose. It may not be sold. Cover picture shows Ben Bulben, County Sligo, Ireland. Contents To return to the Contents list at any time, click on the arrow ↑ before each poem. Introduction From The Wanderings of Oisin and other poems (1889) The Song of the Happy Shepherd The Indian upon God The Indian to his Love The Stolen Child Down by the Salley Gardens The Ballad of Moll Magee The Wanderings of Oisin (extracts) From The Rose (1893) To the Rose upon the Rood of Time Fergus and the Druid The Rose of the World The Rose of Battle A Faery Song The Lake Isle of Innisfree The Sorrow of Love When You are Old Who goes with Fergus? The Man who dreamed of Faeryland The Ballad of Father Gilligan The Two Trees From The Wind Among the Reeds (1899) The Lover tells of the Rose in his Heart The Host of the Air The Unappeasable Host The Song of Wandering Aengus The Lover mourns for the Loss of Love He mourns for the Change that has come upon Him and his Beloved, and longs for the End of the World He remembers Forgotten Beauty The Cap and Bells The Valley of the Black Pig The Secret Rose The Travail of Passion The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers He wishes his Beloved were Dead He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven From In the Seven Woods (1904) In the Seven Woods The Folly of being Comforted Never Give All the Heart The Withering of the Boughs Adam’s Curse Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Untitled.Pdf

STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF W. B. YEATS A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfil£ment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by Barbara L. Croft August 1970 l- ----'- _ u /970 (~ ~ 7cS"' STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF w. B. YEATS by Barbara L. Croft Approved by CGJmmittee: J4 .2fn., k ~~1""-'--- 7~~~ tI It t ,'" '-! -~ " -i L <_ j t , }\\ ) '~'l.p---------"'----------"? - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION ••••• . 1 2. COMPLETE OBJECTIVITY . • • . 23 3. THE DISCOVERY OF STRENGTH •••••••• 41 4. C~1PLETE SUBJECTIVITY •• • • • ••• 55 5. THE BREAKING OF STRENGTH ••••••••• 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 i1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There is, needless to say, an abundance of criticism on W. B. Yeats. Obsessed with the peet's occultism, critics have pursued it to a depth which Yeats, a notedly poor scholar, could never have equalled; nor could he have matched their zeal for his politics. While it is not the purpose here to evaluate or even extensively to examine this criticism, two critics in particular, Richard Ellmann and John Unterecker, will preve especially valuable in this discussion. Ellmann's Yeats: ----The Man and The Masks is essentially a critical biography, Unterecker's ! Reader's Guide l! William Butler Yeats, while it uses biographical material, attempts to fecus upon critical interpretations of particular poems and groups of poems from the Collected Poems. In combination, the work of Ellmann and Unterecker synthesize the poet and his poetry and support the thesis here that the pattern which Yeats saw emerging in his life and which he incorporated in his work is, structurally, the same pattern of a death and rebirth cycle which he explicated in his philosophical book, A Vision. -

Yeats As Precursor Readings in Irish, British And

Yeats as Precursor Readings in Irish, British and American Poetry Steven Matthews Yeats as Precursor Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromso - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-18 - PalgraveConnect Tromso i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230599482 - Yeats as Precursor, Steven Matthews Also by Steven Matthews IRISH POETRY: Politics, History, Negotiation LES MURRAY (forthcoming) REWRITING THE THIRTIES: Modernism and After (co-editor with Keith Williams) Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromso - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-18 - PalgraveConnect Tromso i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230599482 - Yeats as Precursor, Steven Matthews Yeats as Precursor Readings in Irish, British and American Poetry Steven Matthews Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromso - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-18 - PalgraveConnect Tromso i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230599482 - Yeats as Precursor, Steven Matthews First published in Great Britain 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0–333–71147–5 First published in the United States of America 2000 by ST. MARTIN’S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 0–312–22930–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matthews, Steven, 1961– Yeats as precursor : readings in Irish, British, and American poetry / Steven Matthews. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–312–22930–5 1. -

The Art of William Butler and Jack Yeats. Artsedge Curricula, Lessons and Activities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 330 CS 511 355 AUTHOR Karsten, Jayne TITLE Magic Words, Magic Brush: The Art of William Butler and Jack Yeats. ArtsEdge Curricula, Lessons and Activities. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Arts (NFAH), Washington, DC.; MCI WorldCom, Arlington, VA.; Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 25p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/ teaching_materials/curricula/curricula.cfm?subject_id=LNA. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Expression; Class Activities; *Classroom Techniques; *Cultural Context; *Foreign Countries; Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; *Poetry; Secondary Education; Student Educational Objectives; Teacher Developed Materials; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS Ireland; *Yeats (William Butler) ABSTRACT This curriculum unit, designed for grades 7-12, integrates various artistic disciplines with geography, history, social studies, media, and technology. This unit on William Butler Yeats, the writer, and Jack Yeats, the painter, seeks to immerse students in a study of the brothers as voices of Ireland and as two of the most renowned artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The unit is dedicated also to helping students see how the outlook of an age controls cultural expression, and how this expression is articulated in similar ways throughout genres of art. To help effect these major goals, focus in the unit is placed on: the impact of geography, place, and family on both William Butler Yeats and Jack Yeats; the influence of personalities of the time period on the two artists;. -

The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 7 December 1983 The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats Lance Olsen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.215-220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Olsen: The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats by LANCE OLSEN UCH has been said about Yeats's mind working in terms of some M thing akin to the Hegelian dialectical triad in which a thesis and antithesis find resolution in a synthesis. Hegel, in whom Yeats was read ing widely by the middle of the 1920's, and toward whom the poet main tained a strong ambivalence throughout his life, would have it that it is in this dialectical triad "and in the comprehension of the unity of oppo sites, or of the positive in the negative, that speculative knowledge con sists."l But for Yeats the various sets of opposites he found in the world remained unresolved no matter how hard he fought toward resolution. In the running battle he had with them, he always failed to synthesize the diverse virtues in his many-sided debate with himself. The theses and antitheses with which he struggled never attained triadic unity. Instead, they survived as a series of clashing binaries: art/nature; youth/age; body/soul; passion/wisdom; beast/man; a Nietzschean Apollonian/ Dionysian; revelation /civilization; poetry/responsibility; time /eternity; being/becoming; the heroic/the non-heroic; and, finally, the ultimate dialectic between antitheses themselves and a Platonically ideal realm where antitheses in the end are annihilated. -

Literary Review

A BIRD’S EYE VIEW: EXPLORING THE BIRD IMAGERY IN THE LYRIC POETRY OF WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS By ERIN ELIZABETH RISNER A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Studies Division of Ohio Dominican University Columbus, Ohio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTERS OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2013 2 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL A BIRD’S EYE VIEW: EXPLORING THE BIRD IMAGERY IN THE LYRIC POETRY OF WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS By ERIN ELIZABETH RISNER Thesis Approved: _______________________________ ______________ Dr. Ronald W. Carstens, Ph.D. Date Professor of Political Science Chair, Liberal Studies Program ________________________________ ______________ Dr. Martin R. Brick, Ph.D. Date Assistant Professor of English _________________________________ ______________ Dr. Ann C. Hall, Ph. D. Date Professor of English 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. Martin Brick for all of his help and patience during this long, but rewarding, process. I also wish to thank Dr. Ann Hall for her final suggestions on this thesis and her Irish literature class two years ago that began this journey. A special thank you to Dr. Ron Carstens for his final review of this thesis and guidance through Ohio Dominican University’s MALS program. I must also give thanks to Dr. Beth Sutton-Ramspeck, who has guided me through academia since English Honors my freshman year at OSU-Lima. Final acknowledgements go to my family and friends. To my husband, Axle, thank you for all of your love and support the past three years. To my parents, Bob and Liz, I am the person I am today because of you. -

INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL of DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita

INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita Dirks ISSN: 2515-0073 Date of Acceptance: 1 June 2018 Date of Publication: 21 June 2018 Citation: Rita Dirks, ‘Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 1 (2018), 35-55. volupte.gold.ac.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita Dirks Ambrose University Canada has never produced a major man of letters whose work gave a violent shock to the sensibilities of Puritans. There was some worry about Carman, who had certain qualities of the fin de siècle poet, but how mildly he expressed his queer longings! (E. K. Brown) Decadence came to Canada softly, almost imperceptibly, in the 1880s, when the Confederation poet Bliss Carman published his first poems and met the English chronicler and leading poet of Decadence, Arthur Symons. The event of Decadence has gone largely unnoticed in Canada; there is no equivalent to David Weir’s Decadent Culture in the United States: Art and Literature Against the American Grain (2008), as perhaps has been the fate of Decadence elsewhere. As a literary movement it has been, until a recent slew of publications on British Decadence, relegated to a transitional or threshold period. As Jason David Hall and Alex Murray write: ‘It is common practice to read [...] decadence as an interstitial moment in literary history, the initial “falling away” from high Victorian literary values and forms before the bona fide novelty of modernism asserted itself’.1 This article is, in part, an attempt to bring Canadian Decadence into focus out of its liminal state/space, and to establish Bliss Carman as the representative Canadian Decadent.