A History of the Regeneration Circuit: from Invention to Patent Litigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Radio Communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE

Army radio communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE Introduction Prior to the outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 many of the techniques to be used in later years for radio communications had already been invented, although most were still at an early stage of practical application. Radio transmitters at that time were predominantly using spark discharge from a high voltage induction coil, which created a series of damped oscillations in an associated tuned circuit at the rate of the spark discharge. The transmitted signal was noisy and rich in harmonics and spread widely over the radio spectrum. The ideal transmission was a continuous wave (CW) and there were three methods for producing this: 1. From an HF alternator, the practical design of which was made by the US General Electric engineer Ernst Alexanderson, initially based on a specification by Reginald Fessenden. These alternators were primarily intended for high-power, long-wave transmission and not suitable for use on the battlefield. 2. Arc generator, the practical form of which was invented by Valdemar Poulsen in 1902. Again the transmitters were high power and not suitable for battlefield use. 3. Valve oscillator, which was invented by the German engineer, Alexander Meissner, and patented in April 1913. Several important circuits using valves had been produced by 1914. These include: (a) the heterodyne, an oscillator circuit used to mix with an incoming continuous wave signal and beat it down to an audible note; (b) the detector, to extract the audio signal from the high frequency carrier; (c) the amplifier, both for the incoming high frequency signal and the detected audio or the beat signal from the heterodyne receiver; (d) regenerative feedback from the output of the detector or RF amplifier to its input, which had the effect of sharpening the tuning and increasing the amplification. -

1 Thursday, November 19, 2020 12:00 PM

Thursday, November 19, 2020 12:00 PM - 1:00 PM Eastern Time Elizabeth Velez | Chair, New York Building Congress “Social Responsibility – Economic Empowerment” Use our Voices to Advocate Directly in the Industry; High Level Economic Look at 2021/2022 Elizabeth Velez is an outspoken advocate for diversity and inclusion, and a sought after speaker on construction and infrastructure, leadership and mentoring. She is the President of the Velez Organization, a 50-year-old family owned and managed construction services firm - creating schools, hospitals and parks throughout New York. She is a Trustee of Boricua College; an accredited private institution serving students through three campuses in NY. She is the Chair of the New York Building Congress – notably the first Latina in its 99-year history. She serves on the advisory boards of numerous NYC and NYS agencies, industry non-profits, and groups supporting mentorship and scholarships for youth. She is a Board Member of Catholic Charities NY, the NYC Police Foundation, the Women’s Builders Council, Columbia University’s Center for Buildings, Infrastructure & Public Space, ACE-Mentor NY and Youthbridge. She serves as a Commissioner on the NYC Advisory Commission on Property Tax Reform, and following the COVID-19 pandemic, serves as Advisory Board Member for the NYS Forward Re-Opening Advisory Board, and on NYC Real Estate & Construction Sector Advisory Council. Following Hurricane Maria’s disastrous landfall, Elizabeth was appointed to Governor Cuomo’s NY Stands with Puerto Rico Recovery & Rebuilding Committee, and she has spearheaded numerous workforce and economic development programs – including a satellite corporate office in Ponce Puerto Rico. -

Bull Electrical-Jun03.Qxd

Constructional Project PRACTICAL RADIO CIRCUITS RAYMOND HAIGH Part 1: Introduction, Simple Receivers and a Headphone Amp. Dispelling the mysteries of radio. This new series features a variety of practical circuits for the set builder and experimenter. owards the end of the 19th century, physicist who first demonstrated the exis- (V. Poulsen), and by mechanical alterna- sending a radio signal a few hun- tence of electromagnetic waves in 1886. tors (E. Alexanderson). Semiconductors T dred yards was considered a major Before the valve era, radio frequency now play an increasing role, but valves are achievement. At the close of the 20th, man oscillations were generated by using an still used in high-power transmitters. was communicating with space probes at electrical discharge to shock-excite a tuned As their name suggests, the waves com- the outermost edge of the solar system. circuit (H. Hertz and G. Marconi), by the prise an electric and a magnetic field No other area of science and technology negative resistance of an electric arc which are aligned at right angles to one has affected the lives of people another. The electric field is more completely. And because it formed by the rapid voltage fluctu- is so commonplace and afford- ations (oscillations) in the aerial. able, it is accepted without a sec- Current fluctuations create the ond thought. The millions who magnetic field. enjoy it, use it, even those whose lives depend upon it, often have HITCHING A RIDE little more than a vague notion of Electromagnetic waves cannot, A) how it works. by themselves, convey any informa- This series of articles will view tion. -

Ideology of the Air

IDEOLOGY OF THE AIR: COMMUNICATION POLICY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN, 1896-1935 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by SETH D. ASHLEY Dr. Stephanie Craft, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled IDEOLOGY OF THE AIR: COMMUNICATION POLICY AND THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN, 1896-1935 presented by Seth D. Ashley a candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________________________________ Professor Stephanie Craft ____________________________________________________________ Professor Tim P. Vos ____________________________________________________________ Professor Charles Davis ____________________________________________________________ Professor Victoria Johnson ____________________________________________________________ Professor Robert McChesney For Mom and Dad. Thanks for helping me explore so many different paths. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I entered the master’s program at the University of Missouri School of Journalism, my aim was to become a practitioner of journalism, but the excellent faculty members I worked with helped me aspire to become a scholar. First and foremost is Dr. Stephanie Craft, who has challenged and supported me for more than a decade. I could not have completed this dissertation or this degree without her. I was also fortunate to have early encounters with Dr. Charles Davis and Dr. Don Ranly, who opened me to a world of ideas. More recently, Dr. Tim Vos and Dr. Victoria Johnson helped me identify and explore the ideas that were most important to me. -

HP 423A Crystal Detector

Errata Title & Document Type: 423A and 8470A Crystal Detector Operating and Service Manual Manual Part Number: 00423-90001 Revision Date: July 1976 About this Manual We’ve added this manual to the Agilent website in an effort to help you support your product. This manual provides the best information we could find. It may be incomplete or contain dated information, and the scan quality may not be ideal. If we find a better copy in the future, we will add it to the Agilent website. HP References in this Manual This manual may contain references to HP or Hewlett-Packard. Please note that Hewlett- Packard's former test and measurement, life sciences, and chemical analysis businesses are now part of Agilent Technologies. The HP XXXX referred to in this document is now the Agilent XXXX. For example, model number HP8648A is now model number Agilent 8648A. We have made no changes to this manual copy. Support for Your Product Agilent no longer sells or supports this product. You will find any other available product information on the Agilent Test & Measurement website: www.agilent.com Search for the model number of this product, and the resulting product page will guide you to any available information. Our service centers may be able to perform calibration if no repair parts are needed, but no other support from Agilent is available. OPERATING AND SERVICE MANUAL - I 423A 8470A CRYSTAL DETECTOR HEWLETT~PACKARD Plint.d: JUtY 191& e H.",len Packard Co. \910 1 " • .' • I .... ,. ", - \, . '. ~ ~.. ". ." , .' " . ..... " 'I. "",:,. • ' Page 2 i\lodel ·123A/8470A 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 10. -

Biographical Sketch: Alan Willner

Biographical Sketch: Alan Willner Alan Willner received a Ph.D. (1988) in Electrical Engineering from Columbia University and a B.A. (1982) in Physics and an Honorary Doctorate (Honoris Causa, 2012) from Yeshiva University. Prof. Willner was a Postdoctoral Member of Technical Staff at AT&T Bell Labs and a Member of Technical Staff at Bellcore. He is currently a Distinguished Professor of Electrical & Computer Engineering and the Steven & Kathryn Sample Chaired Professor of Engineering in the Ming Hsieh Dept. of Electrical & Computer Eng. of the Viterbi School of Eng. at the Univ. of Southern California. Prof. Willner has been a Visiting Professor at Columbia Univ., Univ. College London, and Weizmann Institute of Science. He has been a Member of the U.S. Army Science Board, a Member of the Defense Sciences Research Council (16-member body that provided reports to DARPA Director & Office Directors), and a member on many advisory boards. He was also Founder & CTO of Phaethon Communications, a company whose technology was acquired by Teraxion, that created the ClearSpectrum® dispersion compensator product line which is presently deployed in many commercial 40-Gbit/s systems worldwide. Prof. Willner has received the following honors: Member of the U.S. National Academy of Engineering, International Fellow of the U.K. Royal Academy of Engineering, Presidential Faculty Fellows Award from the White House, Ellis Island Medal of Honor, IEEE Eric Sumner Technical Field Award, Packard Foundation Fellowship in Science & Engineering, John Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, U.S. Dept. of Defense Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship, Fellow of National Academy of Inventors, Institution of Eng. -

Regenerative Radio Receivers 2/1/16, 7:47 PM

regenerative radio receivers 2/1/16, 7:47 PM WWW.ELECTRONICS-TUTORIALS.COM Recommend 28 Share 28 4 •NEW! ‣ - Amazon Electronic Component Packs. Check out the Amazon Electronic Component Packs page. What are the basics of regenerative radio receivers? Foreword - by Ian C. Purdie VK2TIP A regenerative radio receiver is unsurpassed in comparable simplicity, weak signal reception, inherent noise-limiting and agc action and, freedom from overloading and spurious responses. The regenerative radio receiver or, even super-regenerative radio receiver or, "regen" if you prefer, are basically oscillating detector receivers. They are simple detectors which may be used for cw or ssb when adjusted for oscillation or a-m phone when set just below point of oscillation. In contrast direct conversion receivers use a separate hetrodyne oscillator to produce a signal. In the comprehensive electronic project presented here, Charles Kitchin, N1TEV has provided us with a three stage receiver project which overcomes some of the limitations of this type of receiver, principally the provision of an rf amplifier ahead of the detector. We are indeed particularly grateful to "Chuck" Kitchin, a well noted technical author, for sharing this very valuable material with us to use, learn, experiment and above all, to enjoy. Introduction to the regenerative radio receiver project designed by "Chuck" Kitchin, N1TEV The radio described here is a two band short wave receiver which is both very sensitive and very portable. It receives AM, single sideband (SSB), and CW (code) signals over a frequency range of approximately 3.5 to 12MHz. This includes the 80, 40, and 30 meter Ham bands plus several international short wave bands. -

Crystal Receivers for Broadcast Reception

CRYSTAL RECEIVERS FOR BROADCAST RECEPTION BY PERCY W. HARRIS AUTH OR OF "THE A B C OF WIRELE SS " R E-C EI\·I~ G A \':I R EL l':': SS C c:' .''':CERT \\Tf1r :\ HO]\IE-l\[.-\DE C RYSTAL \;ECEI\ -EI~ LONDON THE WIRELESS PRESS, LTD. t 2 & I3, HENRIETTA STREET, w.e. 2 A HOME- MADE C R Y ST AL RECEIVER WITH ADJUSTME NTS F OR B R OADCAST 'NAVE-LE N GTHS A N D E I F F EL T OW E R TIME SI GN ALS. I N ST R UCTIONS FOR BUILDING T H I S S E T ARE G IVEN IN CHAP T E R X , CRYSTAL RECEIVERS FOR BROADCAST RECEPTION BY PERCY \Y HARIUS A UTHOR OF "THE A 13 C OF W I R ELESS," ETC. LOND ON THE WIRELESS PRESS, LTD. 1 2 & 13, HENRIETTA STREET, W.c. 2 NEW YORK: ,\VIlmLESS PRESS INC., 326 BIWADWAY THE WIRELESS PRESS, LTD. FOREIGN AND CO LOAIAL AGEiVCIES: SYDNEY, N.S.vV.: 97, Clarence Street. MELBOURNE: 422 (4, Little CoUins Street. MADRID: La Prensa Radiotelegrafica, 43, Calle de Alcala. GENOA: Agenzia Radiotelegrafica Italiana, Via Varese 3. AMSTERDAM: Nederlandsch Persbureau Radio, 562, Keizersgracht. INTRODUCTION THE advent of broadcast radio-telephony has aroused con siderable interest in the simple forms of wireless receiver, with the result that the crystal detector, \vhich was fast being ousted by the thermionic valve, has once again become popular. Numerous crystal receivers are now on the market, and the beginner in wireless may well feel some con fusion as to their merits. -

History of Diode

HISTORY OF DIODE In electronics, a diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts electric current in only one direction. The term usually refers to a semiconductor diode, the most common type today, which is a crystal of semiconductor connected to two electrical terminals, a P-N junction. A vacuum tube diode, now little used, is a vacuum tube with two electrodes; a plate and a cathode. The most common function of a diode is to allow an electric current in one direction (called the diode's forward direction) while blocking current in the opposite direction (the reverse direction). Thus, the diode can be thought of as an electronic version of a check valve. This unidirectional behavior is called rectification, and is used to convert alternating current to direct current, and extract modulation from radio signals in radio receivers. However, diodes can have more complicated behavior than this simple on-off action, due to their complex non-linear electrical characteristics, which can be tailored by varying the construction of their P-N junction. These are exploited in special purpose diodes that perform many different functions. Diodes are used to regulate voltage (Zener diodes), electronically tune radio and TV receivers (varactor diodes), generate radio frequency oscillations (tunnel diodes), and produce light (light emitting diodes). Diodes were the first semiconductor electronic devices. The discovery of crystals' rectifying abilities was made by German physicist Ferdinand Braun in 1874. The first semiconductor diodes, called cat's whisker diodes were made of crystals of minerals such as galena. Today most diodes are made of silicon, but other semiconductors such as germanium are sometimes used. -

EECS 117A Demonstration 2 Microwave Measurement Instruments

University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 EECS 117 Prof. A. Niknejad EECS 117A Demonstration 2 Microwave Measurement Instruments NAME Introduction. Please review the general sinusoidal wave concepts in Secs. 3.1–3.9 of Inan & Inan. Note carefully Section 3.3. In this demonstration you will learn how to use a “50 ohm” slotted line, crystal detector, and standing wave ratio meter to obtain the wavelength λ and voltage standing wave ratio S on a coaxial transmission line. In a later demonstration you will use these techniques to measure and control impedances and reflection coefficients on a microwave transmission system. The apparatus used is shown below. The slotted line is a (rigid) continuation of the coaxial transmission lines “a” connected at each end. It has a thin slot in its outer conductor, cut along z. A probe rides within (but not touching) the slot to sample the transmission line voltage. The probe can be moved along z, and can also be moved into and out of the slot by means of a micrometer. The probe is connected to a crystal (diode) detector that converts the time-varying microwave voltage to dc. The dc voltage is measured using the standing wave ratio (SWR) meter. MICROMETER HP 415D b SWR METER DETECTOR TUNER HP 612 A UHF SIGNAL a TERMINATION GENERATOR a GR SLOTTED LINE POINT (LOAD) Z = 0 Z Suppose a sinusoidal voltage wave j(ωt−βz) v+(t) = Re hV+ e i (1) travels from the RF generator through the slotted line and is incident on a load (resistor, capacitor etc.) at z = 0. -

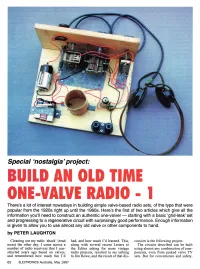

Build an Old Time One-Valve Radio T

•~ a.. e e Ifito .ega'3a, . tr Ssc~ . a~:r"..,`'r"'~g~~ t.~.= ~ y~~..i•'`'E~;sr,:~ .?-~`.r ;~'~I:i'Y ~~":'-:2i:5'-~'r:" *: ap~ i d -.t e -•i' e'•,y`. z'a--'~ ~a.r •~`,`'t ,'-yerk',t"3-c .rLt ~`u"r. ,~,`.~f'F' 06***104r"' G: _•ad2r. r,`r,*•r--,.x-00-fti;,s -,yr-4.o o-+J-0,0_4 03-c?'rv7-F * Special `nostalgia' project: BUILD AN OLD TIME ONE-VALVE RADIO T There's a lot of interest nowadays in building simple valve-based radio sets, of the type that were popular from the 1920s right up until the 1960s. Here's the first of two articles which give all the information you'll need to construct an authentic one-valver starting with a basic `grid-leak' set and progressing to a regenerative circuit with surprisingly good performance. Enough information is given to allow you to use almost any old valve or other components to hand. by PETER LAUGHTON Cleaning out my radio `shack' (read had, and how much I'd learned. This, cussion is the following project. mess) the other day, I came across a along with several recent Letters to The circuits described can be built number of radio receivers that I con- the Editor asking for more vintage using almost any combination of com- structed years ago based on valves, radio projects, resulted in me talking ponents, even from junked valve TV and remembered how much fun I'd to Jim Rowe, and the result of that dis- sets. -

A Fully Integrated CMOS Receiver by Dan Shi a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree O

A Fully Integrated CMOS Receiver by Dan Shi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Electrical Engineering) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Michael P. Flynn, Co-Chair Emeritus Research Scientist Jack R. East, Co-Chair Professor John P. Hayes Professor Amir Mortazawi Dan Shi © 2008 All Rights Reserved to my mom, dad, my sister and my wife… ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have been able to finish my dissertation without the guidance of my committee members, the help from friends, and the support from my family and my wife. First, I would like to express my most sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Michael P. Flynn, for instilling in me the qualities of being a good graduate student. His infectious enthusiasm and unlimited zeal have been major driving forces through my graduate career at The University of Michigan. Throughout my doctoral work he encouraged me to develop independent thinking and research skills. And I am particularly grateful for the advice, both technical and personal, that he has given me over the years. I would also like to thank my co-advisor, Dr. Jack R. East. Without his and Professor George I. Haddad’s continuous support, I would never be writing these lines. I would also like to thank the rest of my committee members: Professor Amir Mortazawi and Professor John P. Hayes for their invaluable feedback during my research. I would like to acknowledge Professor Kamal Sarabandi for his support of this research and for providing help during the final testing.