Gender-Responsive Electric Cooking in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCSP Annual Report

MCSP Annual Report FY 2018 October 1, 2017– September 30, 2018 Submission Date: November 6th, 2018 Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-14-00028 Activity Start Date and End Date: October 2016 – April 2019 Activity Manager: Pavani Ram AOR: Nahed Matta Submitted by: Adhish Dhungana, Manager- Maternal & Child Survival Program Save the Children| Airport Gate Area, Shambhu Marg Kathmandu, Nepal GPO Box: 3394 Telephone: +977-1-4468130/4464803 Email: [email protected] This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Acronyms BEmONC Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care CHD Child Health Division CMA Community Medical Assistant CRS Contraceptive Retail Sales CSD Curative Service Division DDA Department of Drug Administration DHO District Health Office DoHS Department of Health Services DIP Detail Implementation Plan ENAP Every Newborn Action Plan FB IMNCI Facility Based Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness FHD Family Health Division GoN Government of Nepal IMNCI Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness MCSP Maternal and Child Survival Program M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEL Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning MNH Maternal and Newborn Health MNHI Maternal and Newborn Health Integration MoHP Ministry of Health and Population NCDA Nepal Chemist and Druggist Association NHRC Nepal Health Research Council NYI Newborns and Young Infants PI Principle Investigator PSBI Possible Severe Bacterial Infection PSD Partner for Social Development Nepal SBA Skilled Birth Attendant SCI Save the Children International SDG Sustainable Development Goal SNL Saving the Newborn Lives TAG Technical Advisory Group ToR Terms of Reference USAID United States Agency for International Development WHO World Health Organization WIRB Western Institutional Review Board Contents Acronyms 2 FINANCIAL INFORMATION Error! Bookmark not defined. -

S.N Ben Type District Gp Np Ward Pa Grievant Name

S.N BEN_TYPE DISTRICT GP_NP WARD PA GRIEVANT_NAME SLIP_NUMBER GID 1 RCB Dhading Galchi Rural Municipality 4 P-30-5-4-0-0162 Ram Chandra Mijar 15058883 180417 2 RCB Dhading Rubi valley Rural Municipality 4 P-30-11-4-0-0140 Shantabir Gurung 1577737 177978 3 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 2 P-30-8-2-0-0141 Krishna Bahadur Tamang 1530903 185813 4 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 3 P-30-8-3-0-0164 Chature Tamang 1540977 185782 5 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 3 P-30-8-3-0-0167 Shankar Prasad Sigdel 1500782 177047 6 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 3 P-30-8-3-0-0166 Ram Bahadur Basnet 1540990 185689 7 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 7 P-30-8-7-0-0168 Ram Bahadur Khadka 1500882 188926 8 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 6 P-30-8-6-0-0142 Binod Lama 1515793 189514 9 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 2 P-30-8-2-0-0163 Kanchhi Karki 1515896 185718 10 RCB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 3 P-30-8-3-0-0165 Dharma Raj Sunar 1530926 185887 11 RTB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 3 RP-30-8-3-0-0200 Ram Bahadur Shahi 1515758 189359 12 RTB Dhading Thakre Rural Municipality 3 RP-30-8-3-0-0201 Uttam Prasad Aryal 1540997 185694 13 RTB Dolakha Bhimeshwor Municipality 5 RP-22-2-5-0-0202 Laxman Bhujel 1532906 122005 14 RCB Dolakha Bhimeshwor Municipality 2 P-22-2-2-0-0038 Pooja Laxmi Shrestha 1505544 15 RCB Dolakha Bigu Rural Municipality 6 P-22-7-6-0-0106 Dilbahadur Thami 1510141 127273 16 RCB Dolakha Bigu Rural Municipality 4 P-22-7-4-0-0104 Ramkumari Khadka 1520319 117171 17 RCB Dolakha Bigu Rural Municipality 6 P-22-7-6-0-0107 -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Interactions Between Improved Rural Access Infrastructure and Transport Services Provision

Interactions between improved rural access infrastructure and transport services provision Report of Nepal Surveys Paul Starkey, Robin Workman and John Hine TRL ReCAP GEN2136A April 2020 Preferred citation: Starkey, P., Workman R. and Hine, J., TRL (2020). Interactions between improved rural access infrastructure and transport services provision: Report of Nepal Surveys. ReCAP GEN2136A. London: ReCAP for DFID. For further information, please contact: Robin Workman, Principal International Consultant, TRL: [email protected] TRL, Crowthorne House, Nine Mile Ride, Wokingham RG40 3GA, UK ReCAP Project Management Unit Cardno Emerging Market (UK) Ltd Clarendon Business Centre Level 5, 42 Upper Berkeley Street Marylebone, London W1H 5PW The views in this document are those of the authors and they do not necessarily reflect the views of the Research for Community Access Partnership (ReCAP) or Cardno Emerging Markets (UK) Ltd for whom the document was prepared Cover photo: Paul Starkey: Bus rounding hairpin bend with stone soling on the Kavre road studied in Nepal Quality assurance and review table Version Author(s) Reviewer(s) Date 1.1 P Starkey, R Workman and J Hine G Morosiuk (TRL) 10 December 2019 A Bradbury (ReCAP PMU) 18 December 2019 1.2 P Starkey, R Workman and J Hine G Morosiuk (TRL) 27 January 2020 A Bradbury (ReCAP PMU) 10 February 2020 Nite Tanzarn and Dang Thi Kim 18 March 2020 (ReCAP Technical Panel) 1.3 P Starkey, R Workman and J Hine A Bradbury (ReCAP PMU) 11 April 2020 ReCAP Database Details: Interactions between improved rural -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

S.N Local Government Bodies EN स्थानीय तहको नाम NP District

S.N Local Government Bodies_EN थानीय तहको नाम_NP District LGB_Type Province Website 1 Fungling Municipality फु ङलिङ नगरपालिका Taplejung Municipality 1 phunglingmun.gov.np 2 Aathrai Triveni Rural Municipality आठराई त्रिवेणी गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 aathraitribenimun.gov.np 3 Sidingwa Rural Municipality लिदिङ्वा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sidingbamun.gov.np 4 Faktanglung Rural Municipality फक्ताङिुङ गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 phaktanglungmun.gov.np 5 Mikhwakhola Rural Municipality लि啍वाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 mikwakholamun.gov.np 6 Meringden Rural Municipality िेररङिेन गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 meringdenmun.gov.np 7 Maiwakhola Rural Municipality िैवाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 maiwakholamun.gov.np 8 Yangworak Rural Municipality याङवरक गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 yangwarakmuntaplejung.gov.np 9 Sirijunga Rural Municipality लिरीजङ्घा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sirijanghamun.gov.np 10 Fidhim Municipality दफदिि नगरपालिका Panchthar Municipality 1 phidimmun.gov.np 11 Falelung Rural Municipality फािेिुुंग गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalelungmun.gov.np 12 Falgunanda Rural Municipality फा쥍गुनन्ि गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalgunandamun.gov.np 13 Hilihang Rural Municipality दिलििाङ गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 hilihangmun.gov.np 14 Kumyayek Rural Municipality कु म्िायक गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 kummayakmun.gov.np 15 Miklajung Rural Municipality लि啍िाजुङ गाउँपालिका -

Ministry of Finance Financial Comptroller General Office Anamnagar, Kathmandu

An Integrated Financial Code, Classification and Explanation 2074 B.S (Second Revision) Government of Nepal Ministry of Finance Financial Comptroller General Office Anamnagar, Kathmandu WWW.fcgo.gov.np Approved for the operation of economic transaction of three level of government pursuant to the federal structure. Integrated Financial Code, Classification and Explanation, 2074 (Second Revision) (Date of approval by Financial Comptroller General: 2076/02/15) Government of Nepal Ministry of Finance Financial Comptroller General Office Anamnagar, Kathmandu Table of Contents Section – One Budget and Management of Office Code 1 Financial code and classification, and basis of explanation and implementation system 1.1 Budget Code of Government of Nepal 1.2 Office Code of expenditure units of Government of Nepal 1.3 Office Code of the Ministry/organizations of Provincial Government 1.4 Office Code of Local Level 1.5 Code indicating the nature of expenditure 1.6 Code of Donor Agency 1.7 Mode of Receipt/Payment 1.8 Budget Service and Functional Classification 1.9 Code of Province and District Section – Two Classification of Integrated Financial Code and Explanation 2.1 Code of Revenue, classification and explanation 2.2 Code of current expenditure, classification and explanation 2.3 Code of Capital expenditure/assets and liability, classification and explanation 2.4 Code of financial assets and liability (Financial System), classification and explanation 2.5 Code of the balance of assets and liability, description and explanation Section – Three Budget Sub-head of local level Part– one Management of Budget and Office Code 1. The basis of financial code and classification and explanation and its system of implementation The constitution of Nepal has made provision for a separate treasury fund in all three levels of government (Federal, Province and Local), and accounting format for economic transaction as approved by the auditor general. -

![NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3032/nepal-kabhrepalanchok-operational-presence-map-as-of-14-july-2015-2093032.webp)

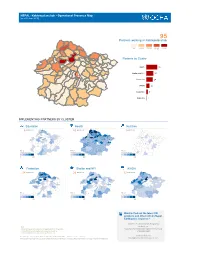

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 14 July 2015] Gairi Bisauna Deupur Baluwa Pati Naldhun Mahadevsthan Mandan Naya Gaun Deupur Chandeni Mandan 86 Jaisithok Mandan Partners working in Kabhrepalanchok Anekot Tukuchanala Devitar Jyamdi Mandan Ugrachandinala Saping Bekhsimle Ghartigaon Hoksebazar Simthali Rabiopi Bhumlutar 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-35 Nasikasthan Sanga Banepa Municipality Chaubas Panchkhal Dolalghat Ugratara Janagal Dhulikhel Municipality Sathigharbhagawati Sanuwangthali Phalete Mahendrajyoti Bansdol Kabhrenitya Chandeshwari Nangregagarche Baluwadeubhumi Kharelthok Salle Blullu Ryale Bihawar No. of implementing partners by Sharada (Batase) Koshidekha Kolanti Ghusenisiwalaye Majhipheda Panauti Municipality Patlekhet Gotpani cluster Sangkhupatichaur Mathurapati Phulbari Kushadevi Methinkot Chauri Pokhari Birtadeurali Syampati Simalchaur Sarsyunkharka Kapali Bhumaedanda Health 37 Balthali Purana Gaun Pokhari Kattike Deurali Chalalganeshsthan Daraunepokhari Kanpur Kalapani Sarmathali Dapcha Chatraebangha Dapcha Khanalthok Boldephadiche Chyasingkharka Katunjebesi Madankundari Shelter and NFI 23 Dhungkharka Bahrabisae Pokhari Narayansthan Thulo Parsel Bhugdeu Mahankalchaur Khaharepangu Kuruwas Chapakhori Kharpachok Protection 22 Shikhar Ambote Sisakhani Chyamrangbesi Mahadevtar Sipali Chilaune Mangaltar Mechchhe WASH 13 Phalametar Walting Saldhara Bhimkhori Education Milche Dandagaun 7 Phoksingtar Budhakhani Early Recovery 1 Salme Taldhunga Gokule Ghartichhap Wanakhu IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Early Recovery -

Npl Eq Operational Presence K

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 30 June 2015] 95 Partners working in Kabrepalanchok 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-40 Partners by Cluster Health 40 Shelter and NFI 26 Protection 24 WASH 12 Education 6 Nutrition 1 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Education Health Nutrition 6 partners 40 partners 1 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 20 1 40 1 20 Protection Shelter and NFI WASH 24 partners 26 partners 12 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 30 1 30 1 20 Want to find out the latest 3W products and other info on Nepal Earthquake response? visit the Humanitarian Response Note: website at Implementing partner represent the organization on the ground, http:www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/op in the affected area doing the operational work, such as erations/nepal distributing food, tents, doing water purification, etc. send feedback to Creation date: 10 July 2015 Glide number: EQ-2015-000048-NPL Sources: Cluster reporting [email protected] The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Kabrepalanchok District Include all activity types in this report? TRUE Showing organizations for all activity types Education Health Nutrition Protection Shelter and NFI WASH VDC Name MSI,UNICEF,WHO AWN,UNWomen,SC N-Npl SC,WA Anekot Balthali UNICEF,WHO MC UNICEF,CN,MC Walting UNICEF,WHO CECI SC,UNICEF TdH AmeriCares,ESAR,UNICEF,UN AAN,UNFPA,KIRDA PI,TdH TdH,UNICEF,WA Baluwa Pati Naldhun FPA,WHO RC Wanakhu UNICEF AWN CECI,GM SC,UNICEF ADRA,TdH Royal Melbourne CIVCT G-GIZ,GM,HDRVG SC,UNICEF Banepa Municipality Hospital,UNICEF,WHO Nepal,CWISH,KN,S OS Nepal Bekhsimle Ghartigaon MSI,UNICEF,WHO N-Npl UNICEF Bhimkhori SC UNICEF,WHO SC,WeWorld SC,UNICEF ADRA MSI,UNICEF,WHO YWN MSI,Sarbabijaya ADRA UNICEF,WA Bhumlutar Pra.bi. -

Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal

ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Before After 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Authors Binod Sharma, Santosh Nepal, Dipak Gyawali, Govinda Sharma Pokharel, Shahriar Wahid, Aditi Mukherji, Sushma Acharya, and Arun Bhakta Shrestha International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, June 2016 i Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2016 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Government of Nepal Roshi Rural Municipality Office of Rural Municipal Executive Katunje, Kavre, Province 3, Nepal

Government of Nepal Roshi Rural Municipality Office of Rural Municipal Executive Katunje, Kavre, Province 3, Nepal Expression of Interest (EOI) for Shortlisting of Consulting Services For the PREPARATION OF TOURISM MASTER PLAN AND DPR OF MAJOR TOURISM INFRASTRUCUTURES OF ROSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY Magh, 2074 1 Expression of Interest (EOI) PREPARATION OF TOURISM MASTER PLAN AND DPR OF MAJOR TOURISM INFRASTRUCUTURES OF ROSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY Method of Consulting Service [National] Project Name : PREPARATION OF TOURISM MASTER PLAN AND DPR OF MAJOR TOURISM INFRASTRUCUTURES OF ROSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY EOI : C-001-074/75 Office Name : Roshi Rural Municipality Office Office Address : Katunje, Kavre, Province 3, Nepal Issued on : 2074/12/14 2 Abbreviations CV - Curriculum Vitae DO - Development Partner EA - Executive Agency EOI - Expression of Interest GON - Government of Nepal PAN - Permanent Account Number PPA - Public Procurement Act PPR - Public Procurement Regulation TOR - Terms of Reference VAT - Value Added Tax 3 Contents A. Request for Expression of Interest .................................................................. 5 B. Instructions for submission of Expression of Interest ................................... 6 C. Objective of Consultancy Services or Brief TOR ............................................ 7 D. Evaluation of Consultant’s EOI Application .................................................. 14 E. EOI Forms & Formats ...................................................................................... 16 1. Letter of -

Community Resilience Capacity

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY A STUDY ON NEPAL’S 2015 EARTHQUAKES AND AFTERMATH Central Department of Anthropology Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY B A STUDY ON NEPAL’S 2015 EARTHQUAKES AND AFTERMATH COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY A STUDY ON NEPAL’S 2015 EARTHQUAKES AND AFTERMATH Mukta S. Tamang In collaboration with Dhanendra V. Shakya, Meeta S. Pradhan, Yogendra B. Gurung, Balkrishna Mabuhang SOSIN Research Team PROJECT COORDINATOR Dr. Dambar Chemjong RESEARCH DIRECTOR Dr. Mukta S. Tamang TEAM LEADERS Dr. Yogendra B Gurung Dr. Binod Pokharel Dr. Meeta S. Pradhan Dr. Mukta S. Tamang TEAM MEMBERS Dr. Dhanendra V. Shakya Dr. Meeta S. Pradhan Dr. Yogendra B. Gurung Mr. Balkrishna Mabuhang Mr. Mohan Khajum ADVISORS/REVIEWERS Dr. Manju Thapa Tuladhar Mr. Prakash Gnyawali I COMMUNITY RESILIENCE CAPACITY A Study on Nepal’s 2015 Earthquakes and Aftermath Copyright @ 2020 Central Department of Anthropology Tribhuvan University This study is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government or Tribhuvan University. Published by Central Department of Anthropology (CDA) Tribhuvan University (TU), Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: + 977- 01-4334832 Email: [email protected] Website: www.anthropologytu.edu.np First Published: October 2020 300 Copies Cataloguing in Publication Data Tamang, Mukta S. Community resilience capacity: a study on Nepal’s 2015 earthquakes and aftermath/ Mukta S.Tamang …[ et al. ] Kirtipur : Central Department of Anthropology, Tribhuvan University, 2020.