Power, Violence, and Sexuality in Urban Fantasy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

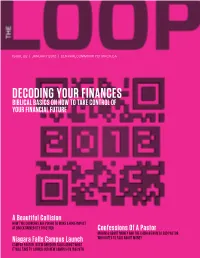

Decoding Your Finances Biblical Basics on How to Take Control of Your Financial Future

ISSUE 22 | JANUARY 2012 | CENTRALCOMMUNITYCHURCH.CA DECODING YOUR FINANCES BIBLICAL BASICS ON HOW TO TAKE CONTROL OF YOUR FINANCIAL FUTURE A Beautiful Collision HOW TWO CHURCHES ARE POISED TO MAKE A HUGE IMPACT AT BROCK UNIVERSITY TOGETHER Confessions Of A Pastor MUSINGS ABOUT MONEY AND THE CHURCH FROM A LEAD PASTOR Niagara Falls Campus Launch Who HATES TO TALK ABOUT MONEY campus pastor Justin driedger talks about What it Will take to launch our neW campus on Jan 28th WE are putting the call out WE are looking for talented neW musicians to be A part of the central team at all 4 of our campuses if you are interested in being A part of the team simply come and meet one of our Worship leaders in the lobby ON Sunday January 15 & 22 to start the process. Need To Know 10 partnership Why partnership matters and how to become a partner at Central. BY EMILY SLUYS 8 12 confessions OF A pastor A BEAUTIFUL COLLISION A candid and honest look at life, faith and church from the The launch of our new Collide perspective of Lead Pastor Bill student ministry partnership with Markham. Southridge on campus at Brock. BY BILL MARKHAM WELCOME TO CENTRAL BY ROY OLENDE 2012 is now here. We are starting off the New Year as a church with a look at money. This particular subject matter tends to elicit an extreme range of emotions from us and is generally uncomfortable to deal with as a whole church in a public 19 way, but I’m not convinced it should be that way. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

End Of Year Charts 2003 CHART #20039999 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums STAND UP / NOT MANY LOST WITHOUT YOU BEAUTIFUL COLLISION STRIPPED 1 Scribe 21 Delta Goodrem 1 Bic Runga 21 Christina Aguilera Last week 0 / 0 weeks DIRTY/FMR Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks BMG WHERE IS THE LOVE? BRING ME TO LIFE COME AWAY WITH ME HOME 2 Black Eyed Peas 22 Evanesence 2 Norah Jones 22 Dixie Chicks Last week 0 / 0 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks CAPITOL/EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY BEAUTIFUL NU-FLOW A RUSH OF BLOOD TO THE HEAD REVIVAL - BONUS DISC 3 Christina Aguilera 23 Big Brovaz 3 Coldplay 23 Katchafire Last week 0 / 0 weeks BMG Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks CAPITOL/EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks SHOCK/BMG IN DA CLUB CRAZY IN LOVE POLYSATURATED ON AND ON 4 50 Cent 24 Beyonce feat. Jay Z 4 Nesian Mystik 24 Jack Johnson Last week 0 / 0 weeks UNIVERSAL Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks BOUNCE/UNIVERSAL Last week 0 / 0 weeks CAPITOL/EMI BORN TO TRY SORRY SEEMS TO BE THE HARD... AUDIOSLAVE ROOM FOR SQUARES 5 Delta Goodrem 25 Blue. Feat Elton John 5 Audioslave 25 John Mayer Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks VIRGIN/EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY FLAKE RIGHT THURR FALLEN THE RECORD 6 Jack Johnson 26 Chingy 6 Evanescence 26 Bee Gees Last week 0 / 0 weeks CAPITOL/EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks CAPITOL/EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks UNIVERSAL IF YOU'RE NOT THE ONE WHITE FLAG BRUSHFIRE FAIRYTALES -

Core Collections in Genre Studies Romance Fiction

the alert collector Neal Wyatt, Editor Building genre collections is a central concern of public li- brary collection development efforts. Even for college and Core Collections university libraries, where it is not a major focus, a solid core collection makes a welcome addition for students needing a break from their course load and supports a range of aca- in Genre Studies demic interests. Given the widespread popularity of genre books, understanding the basics of a given genre is a great skill for all types of librarians to have. Romance Fiction 101 It was, therefore, an important and groundbreaking event when the RUSA Collection Development and Evaluation Section (CODES) voted to create a new juried list highlight- ing the best in genre literature. The Reading List, as the new list will be called, honors the single best title in eight genre categories: romance, mystery, science fiction, fantasy, horror, historical fiction, women’s fiction, and the adrenaline genre group consisting of thriller, suspense, and adventure. To celebrate this new list and explore the wealth of genre literature, The Alert Collector will launch an ongoing, occa- Neal Wyatt and Georgine sional series of genre-themed articles. This column explores olson, kristin Ramsdell, Joyce the romance genre in all its many incarnations. Saricks, and Lynne Welch, Five librarians gathered together to write this column Guest Columnists and share their knowledge and love of the genre. Each was asked to write an introduction to a subgenre and to select five books that highlight the features of that subgenre. The result Correspondence concerning the is an enlightening, entertaining guide to building a core col- column should be addressed to Neal lection in the genre area that accounts for almost half of all Wyatt, Collection Management paperbacks sold each year.1 Manager, Chesterfield County Public Georgine Olson, who wrote the historical romance sec- Library, 9501 Lori Rd., Chesterfield, VA tion, has been reading historical romance even longer than 23832; [email protected]. -

Paranormal Romance Guide Adair, Cherry. “Black Magic.”

Paranormal Romance Guide Adair, Cherry. “Black Magic.” Pocket Star. Ever since the death of her parents, Sara Temple has rejected her magical gifts. Then, in a moment of extreme danger, she unknowingly sends out a telepathic cry for help; to the one man she is convinced she never wants to see again. Jackson Slater thought he was done forever with his ex-fiance, but when he hears her desperate plea, he teleports halfway around the world to aid her in a situation where magic has gone suddenly, brutally wrong. But while Sara and Jack remain convinced they are completely mismatched, the Wizard Council feels otherwise. A dark force is killing some of the world’s most influential wizards, and the ex-lovers have just proved their abilities are mysteriously amplified when they work together. But with the fate of the world at stake, will the violent emotions still simmering between them drive them farther apart or bring them back together? Alexander, Cassie. “Nightshifted.” St. Martin’s Press. Nursing school prepared Edie Spence for a lot of things. Burn victims? No problem. Severed limbs? Piece of cake. Vampires? No way in hell. But as the newest nurse on Y4, the secret ward hidden in the bowels of County Hospital, Edie has her hands full with every paranormal patient you can imagine, from vamps and were-things to zombies and beyond. Edie’s just trying to learn the ropes so she can get through her latest shift unscathed. But when a vampire servant turns to dust under her watch, all hell breaks loose. -

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance

SBR Media Catalog of Works Genre: Romance This catalog features the novels available for foreign translation and audio rights purchases. SBR Media is owned by Stephanie Phillips Contact: [email protected] Phone: 843.421.7570 SBR Media 3761 Renee Dr. Suite #223 Myrtle Beach, SC 29526 The information in this catalog is accurate as of July 29, 2020. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. SBR Media Catalog of Works .................................................................................................................... 1 Alexis Noelle ............................................................................................................................................... 14 Her Series : Contemporary Suspense ...................................................................................................... 14 Keeping Her ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Deathstalkers MC Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................... 15 Corrupted ............................................................................................................................................. 15 Shattered Series : Contemporary Suspense ............................................................................................. 15 Shattered Innocence ............................................................................................................................ -

Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel

Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel by Christina Vani A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Christina Vani 2018 Immortal Words: the Language and Style of the Contemporary Italian Undead-Romance Novel Christina Vani Doctor of Philosophy Department of Italian Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis explores the language and style of six “undead romances” by four contemporary Italian women authors. I begin by defining the undead romance, trace its roots across horror and romance genres, and examine the subgenres under the horror-romance umbrella. The Trilogia di Mirta-Luna by Chiara Palazzolo features a 19-year-old sentient zombie as the protagonist: upon waking from death, Mirta-Luna searches the Subasio region for her love… but also for human flesh. These novels present a unique interpretation of the contemporary “vampire romance” subgenre, as they employ a style influenced by Palazzolo’s American and British literary idols, including Cormac McCarthy’s dialogic style, but they also contain significant lexical traces of the Cannibali and their contemporaries. The final three works from the A cena col vampiro series are Moonlight rainbow by Violet Folgorata, Raining stars by Michaela Dooley, and Porcaccia, un vampiro! by Giusy De Nicolo. The first two are fan-fiction works inspired by Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Saga, while the last is an original queer vampire romance. These novels exhibit linguistic and stylistic traits in stark contrast with the Trilogia’s, though Porcaccia has more in common with Mirta-Luna than first meets the eye. -

Released 28Th October 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS JUN150091

Released 28th October 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS JUN150091 BURROUGHS TARZAN SUNDAY COMICS 1935-1937 HC VOL 03 AUG150028 COLDER TOSS THE BONES #2 JUN150092 COMPLETE LOVE HURTS TP AUG150071 CONAN THE AVENGER #19 AUG150025 CREEPY COMICS #22 AUG150027 DEATH HEAD #4 JUN150089 EC ARCHIVES HAUNT OF FEAR HC VOL 02 AUG150048 FIGHT CLUB 2 #6 MACK MAIN CVR JUN150102 GANTZ TP VOL 37 (MR) JUN150088 GREEN RIVER KILLER A TRUE DETECTIVE STORY TP AUG150066 HALO ESCALATION #23 AUG150020 HELLBOY & BPRD 1953 PHANTOM HAND & KELPIE JUN150033 MURDER MYSTERIES AND OTHER STORIES HC GALLERY EDITION JUN150095 OREIMO KURONEKO TP VOL 03 AUG150050 PASTAWAYS #7 AUG150060 PLANTS VS ZOMBIES GARDEN WARFARE #1 JUN158297 PLANTS VS ZOMBIES HC BULLY FOR YOU AUG150051 TOMORROWS #4 DC COMICS AUG150205 ALL STAR SECTION 8 #5 AUG150177 AQUAMAN #45 AUG150285 ART OPS #1 (MR) AUG150227 BATGIRL #45 AUG150231 BATMAN 66 #28 JUL150309 BATMAN ADVENTURES TP VOL 03 AUG150159 BATMAN AND ROBIN ETERNAL #4 JUL150304 BATMAN WAR GAMES TP VOL 01 JUL150299 CONVERGENCE INFINITE CRISIS TP BOOK 01 JUL150301 CONVERGENCE INFINITE CRISIS TP BOOK 02 AUG150184 CYBORG #4 AUG150181 DEATHSTROKE #11 JUN150300 DEATHSTROKE BOOK AND MASK SET JUN150322 FABLES DELUXE EDITION HC VOL 11 (MR) JUL150340 FABLES THE WOLF AMONG US TP VOL 01 (MR) AUG150190 FLASH #45 AUG150239 GOTHAM BY MIDNIGHT #10 AUG150243 GRAYSON #13 AUG150253 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #11 AUG150266 INJUSTICE GODS AMONG US YEAR THREE HC VOL 01 JUL150315 INJUSTICE GODS AMONG US YEAR TWO TP VOL 02 AUG150196 JUSTICE LEAGUE 3001 #5 AUG150168 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARKSEID -

Gavin D. Douglas Curriculum Vitae

Gavin D. Douglas Curriculum Vitae email: [email protected] Academic Position 2008-present Associate Professor, Ethnomusicology (Music Studies Dept. Head 2012-2016) UNC Greensboro. School of Music, Theatre and Dance 2002-2008 Assistant Professor, Ethnomusicology UNC Greensboro. School of Music Education 2001 PHD (Ethnomusicology) — University of Washington Dissertation: State Patronage of Burmese Traditional Music 1993 MMUS (Musicology/Ethnomusicology) — University of Texas at Austin Thesis: Popular Music in Canada: Globalism and the Struggle for National Identity 1991 BA (Philosophy) — Queen’s University 1990 BMUS (Performance Classical Guitar) — Queen’s University Publications (Books) 2010 Music in Mainland Southeast Asia: Experiencing Music Expressing Culture. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Publications (Articles, peer reviewed) Forthcoming “Sound Authority in Burma,” in Sounds of Hierarchy and Power in Southeast Asia. Nathan Porath, ed. NIAS Press In Press ““Buddhist Soundscapes in Myanmar: Dhamma Instruments and Divine States of Consciousness.” Proceedings of the 4th Symposium of the ICTM Study Group on Performing Arts of Southeast Asia. Mohd Anis Md Nor and Patricia Matusky (eds.) Denpasar, Bali: Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI). In Press “Burma/Myanmar: History, Culture, Geography,” in The Sage Encyclopedia of Ethnomusicology, Janet Sturman J. and Geoffrey Golson, eds. In Press “Burma/Myanmar: Contemporary Performance Practice,” in The Sage Encyclopedia of Ethnomusicology, Janet Sturman and Geoffrey Golson, eds. 2015 “Buddhist -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON -

Ambition of Love Reflected in Lauren Kate's Novel Fallen

AMBITION OF LOVE REFLECTED IN LAUREN KATE’S NOVEL FALLEN (2009): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by: AISYAH PRAMUTIKA SANTI A 320080072 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2013 ACCEPTANCE AMBITION OF LOVE REFLECTED IN LAUREN KATE’S NOVEL FALLEN (2009): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH PUBLICATION ARTICLE by: AISYAH PRAMUTIKA SANTI A 320080072 Accepted and Approved by Board of Examiner School of Teacher Training and Education Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta The Board of Examiners 1.Drs. AbdillahNugroho, M. Hum. ( ) (Chair Person) 2. Dr. Phil. Dewi Candraningrum, M. Ed. ( ) (Member I) The Dean of Teacher Training and Education Faculty Dra. N. Setyaningsih, MSi NIK. 403 AMBITION OF LOVE REFLECTED IN LAUREN KATE’S NOVEL FALLEN (2009): A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH AisyahPramutikaSanti Department of English Education [email protected] ABSTRACT The major problem of this study is how ambition of Lucinda Price is reflected in Fallen novel (2009). The objective of this study is to analyze Lucinda Price’sambition in Lauren Kate’s Fallen based on psychoanalytic approach. The object of this study is Fallen novel (2009) by Lauren Kate. This study is literary study, which can be categorized into a descriptive qualitative study. The researcher uses two data sources:primary and secondary data sources. The primary data sources areFallen novel by Lauren Kate and the secondary data sources are related to the primary data that support the analysis such as some books of psychology and website related to the research. The technique of data analysis is descriptive qualitative analysis. -

Frank Millers Sin City Volume 7: Hell and Back 3Rd Edition Free Ebook

FREEFRANK MILLERS SIN CITY VOLUME 7: HELL AND BACK 3RD EDITION EBOOK Frank Miller | 318 pages | 30 Nov 2010 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781593072995 | English | Milwaukie, United States Sin City, Volume 7: Hell and Back * Hell and Back is planned for a future Sin City film, starring Johnny Depp as WallaceHell and Back, the final volume of Frank Miller's signature series, is the biggest and baddest Sin City of them all! This newly redesigned edition features a brand--new cover by Miller--some of his first comics art in years!. This is the seventh and final (so far) book in Frank Miller's Sin City series. This time around, the story stars the new character of "Wallace". Wallace is an artist/war hero who saves a beautiful woman from commiting suicide. The woman ends up getting kidnapped, and Wallace goes to "Hell and back" to rescue her. That's all I will say about the plot. Hell and Back, the final volume of Frank Miller's signature series, is the biggest and baddest Sin City of them all! This newly redesigned edition features a brand--new cover by Miller--some of his first comics art in years! It's one of those clear, cool nights that drops in the middle of summer like a gift from on high. Frank Miller's Sin City Volume 7: Hell and Back 3rd Edition Sin City Volume 7: Hell and Back (3rd Edition) by Miller, Frank and a great selection of related books, art and collectibles available now at Hell and Back is the seventh and final volume in Frank Miller’s SIN CITY series. -

Aliens and Amazons: Myth, Comics and the Cold War Mentality in Fifth-Century Athens and Postwar America

ALIENS AND AMAZONS: MYTH, COMICS AND THE COLD WAR MENTALITY IN FIFTH-CENTURY ATHENS AND POSTWAR AMERICA Peter L. Kuebeck A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2006 Committee: Leigh Ann Wheeler, Advisor James M. Pfundstein Robert Buffington ii ABSTRACT Leigh Ann Wheeler, Advisor Comic books and classical culture seem to be increasingly linked in recent years, whether through crossovers into one another's media or through portrayals in the mass media itself. Such a connection begs the question of the actual cultural relevance between these two particular cultural products and whether or not two such products can be found to be relevant to one another when separated by time and space - indeed, if two separate cultures experienced similar cultural pressures, would these cultural products represent these pressures in similar ways? Given previous scholarly work linking the Cold War-era in the United States and the Peloponnesian War in fifth-century Greece politically, this thesis argued that a cultural "Cold War mentality" existed both in early postwar America and fifth-century Athens, and that this "Cold War mentality" is exhibited similarly in the comic books and mythology produced in those eras. This mentality is comprised of three stages: increased patriotism, a necessary identification of a cultural other, and attempts by a threatened male society to obtain psychological power through the "domestication" of women. The methods of this thesis included cultural research as well as research into myth and comic books of the respective eras.