Cemeteries As Central Places - Place and Identity in Migration Period Eastern England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincolnshire. Pub '16~

TRADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE. PUB '16~ Red Lion, Arthur Forge, 75 & 77 Freeman street, Grimsby Royal Oak, Thomas Watson, North street, Bourne Red Lion, John William Greenwood, Raithby, Spilsby Royal Oak, Henry Whittaker, Heckington S.O .Red Lion, Joshua Gresham, Dunston, Lincoln Royal Oak, Charles Henry Wood, North Kelsey, Lincoln Red Lion, William Grundy, Wellingore, Lincoln Royal Oak, Seth William Wortley, Roman bank, Skegness Red Lion, Charles E. B. Hardy, Swineshead, Boston Royal Vaults, Geo.H. Smith, Waterside rd.Barton-on-Humbr Red Lion, Charles Highway, Baumber, Horncastle Royal William the I<'ourth, Mrs. Ann Glover,Brayford,Lincln Red Lion, John Yorke Hiblin, ll1gby, Lincoln Rum Puncheon, John B. Westland, 40 Market place, Boston Red Liony John Clarke Hodgson, Mumby, Alford RutJand Arms, George Pearson, Woolsthorpe, Grantham Red Lion, Tom William Husbands, so Westgate, Sleaford Rutland Arms, Thomas Taylor, GreatGonerby, Grantbam Red Lion, William Ingram, 45 King street, Market Rasen Rutland Arms, James Watson, Wilsford, Grantham Red Lion, Joseph Jackson, Barrow-on-Humber Salutation inn, William Dawson, Nettleton, Caistor Red Lion, Albert Johnson, Partney, Spilsby Saracen's Head, William Thomas Adcock,Nettleham,Lincoln Red Lion, Mrs. Rosa Johnson, North street, Crowle,Doncstr Saracen's Head, Mrs. Betsy Norton, East Keal, Spilsby Red Lion, Henry Knipe, South street, Boume Saracen's Head, John Searls, Hogsthorpe, Altord Red Lion, Francis Dowse Lake, East end, Alford Saracen's Head, Mrs. E. Teanby, 181 Cleethorpe rd.Grimsby Red Lion, Wm. Marriott, West Deeping, Market Deeping Saracen's Head inn, John Waiter, Bridge street, Horncastle Red Lion, John MarshaJl, Junction sq. Barton-on-Humber Scarborough Arms, Mrs. -

Full Property Address Account Start Date

Property Reference Number Name (Redacted as Personal Data if Blank) Full Property Address Account Start Date 10010080460 46, Alexandra Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 7AP 01/04/2005 10010080463 Lincolnshire County Council Lincs County Council, Alexandra Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 7AP 01/04/2005 10010160350 Avc 35 Ltd The Avenue Veterinary Centre, 35, Avenue Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6TA 01/04/2005 10010615050 Neat Ideas Ltd Unit 5, Belton Lane Industrial Estate, Belton Lane, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 9HN 01/04/2005 10010695200 8, Bridge Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 9AE 01/04/2005 10010710010 2nd Grantham(St Wulframs) Scouts Group 2nd Grantham Scout Group, Broad Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 8AP 01/04/2005 10010720340 The Board Of Governors The Kings School The Kings School, Brook Street, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6PS 01/04/2005 10011150140 14, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SE 01/04/2005 10011150160 16, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SE 01/04/2005 10011150500 Grantham Conservative Club 50, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SN 01/04/2005 10011150660 The Castlegate, 69, Castlegate, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6SJ 01/04/2005 10011290453 The Maltings Dental Practice The Maltings, Commercial Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6DE 01/04/2005 10011300272 South Kesteven District Council South Kesteven District Council, Conduit Lane, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 6LQ 01/04/2005 10011810010 Dudley House School 1, Dudley Road, Grantham, Lincolnshire, NG31 9AA 01/04/2005 10011820020 -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

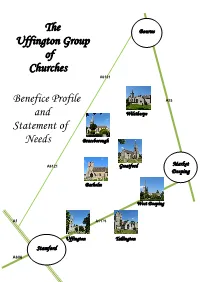

The Uffington Group of Churches Benefice Profile and Statement Of

The Bourne Uffington Group of Churches A6121 Benefice Profile A15 and Wilsthorpe Statement of Needs Braceborough A6121 Greatford Market Deeping Barholm West Deeping A1 A1175 Uffington Tallington Stamford A606 Introduction Thank you for taking an interest in the Uffington Group of Churches. If you are reading this to see whether you might be interested in becoming our next Rector, we hope you will find it helpful. If you are reading this for any other reason, we hope you will find this profile interesting, and if you are in the area, or might just be passing through, we hope that you might wish to come and see us. We hope that our new Rector will be able to inspire us in three key areas of our discipleship growth plans: drawing more of our villagers, especially from the missing generations, to respond to the message of the gospel (ie making more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King might have said); enhancing the faith of current members of our congregations (responding to the need for more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King did say); ensuring that our seven churches are not only kept open and functioning, but are made more attractive focal points for the lives of our parishioners and communities. We believe that such a person is likely to be: someone who will prayerfully seek to preach, teach and share scriptural truth; willing to grasp the nature of rural ministry; able to preserve the identity of each parish while maintaining coherence of the Group; comfortable with a range of worship and broad expression of faith; able to develop and communicate an inspirational vision for building God’s work amongst all ages in the Group and in each parish; able to lead, cultivate and enthuse teams of volunteers involved in the ministry, administration and upkeep of the seven churches; open, approachable and supportive, and willing to be visible at community events in all the villages; keen to guide and support the Christian ethos of the Uffington Church of England Primary School, being a regular visitor to the school and ex-officio governor. -

Monumental Inscriptions SAINT ANDREW's CHURCH WEST

Monumental Inscriptions SAINT ANDREW’S CHURCH WEST DEEPING Lincolnshire Originally recorded by Virginia Hall James Rice and June Thomas Revision, additional research, photography and plan by Margaret A Ashcroft Monumental Inscriptions St Andrew’s Church West Deeping Lincolnshire Margaret A Ashcroft ©2010 M. Ashcroft Copying permitted for educational and private use but not for commercial gain A CD is available, containing this document (MS Office Word file) together with all the photographs in their original resolution and the plan of the church yard in JPEG format. Please contact any of the following for the current cost including postage and packing. Allan Crowson, Church Warden, 17 King Street, West Deeping, Peterborough PE6 9HP Tel: 01778 345393 [email protected] Mrs Rene Cutts, Lay Worker 37 King Street, West Deeping, Peterborough PE6 9HP Tel. 01778 342831 [email protected] M.A.Ashcroft 32 King Street, West Deeping, Peterborough PE6 9HP Tel: 01778 344768 [email protected] All proceeds are for the benefit of St Andrew’s Church, West Deeping, Lincolnshire Monumental Inscriptions St Andrew’s Church West Deeping Lincolnshire CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i - ii INDEX OF SURNAMES iii - vi IN THE CHURCH YARD Pages 1 - 24 1 – 104 IN THE CHURCH Pages 25 - 28 105 - 116 APPENDIX Pages 29 - 30 Grave stones in St Andrew’s Church recorded in 1831 117 - 132 PLAN OF THE CHURCHYARD Insert in back cover & key to Monumental Inscriptions i INTRODUCTION This list of Monumental Inscriptions in the church yard and in the church of St Andrew, West Deeping is based on a survey of inscriptions on the graves in the church yard, undertaken in 2000 or 2001 by Virginia Hall, James Rice and June Thomas. -

Residential Development Land Off Stowe Road, Langtoft

RESIDENTIALSPALDING DEVELOPMENT COMMERCIAL : 01775 : 01775 765536 765536 www.longstaff.com www.longstaff.com By Direction of Gibbons (Holdings) Ltd Residential Development Land Off Stowe Road, Langtoft, Peterborough PE6 9NE FOR SALE - Guide Price: £2,250,000 Freehold, Subject to Contract Approximately 8.62 Acres (3.49 Hectares) Full Consent for 6 Units and Outline Consent for up to 35 Units Popular Village with Good Local Facilities and Amenities, Unique Position Close to Lakes and SSSI Close to Market Deeping and within easy reach of Bourne, Stamford and the Expansion City of Peterborough LOCATION The land is situated on the south side of Stowe Road on the western edge of the village of Langtoft, but within walking distance of local village facilities and amenities, which include Village Shop, Public House, Parish Church, Village Hall and Primary School. Market Deeping lies 2 miles to the south which offers very much more extensive facilities and amenities, including banking, shopping, retail, leisure and primary and secondary education facilities. The market town of Bourne is some 7 miles to the north, also providing extensive market town facilities and amenities and the very large centre of Peterborough, about 10 miles to the south, is also readily accessible. The attractive limestone built town of Stamford, only 7 miles to the south west, also provides the closest connection point to the A1. Train connections are available at Stamford and Peterborough - the east coast main line Peterborough to Kings Cross service is available with a minimum journey time of approximately 45 minutes. Sporting opportunities in the area are also excellent with a large number of indoor and outdoor facilities, together with Golf Courses at Toft (near Bourne), Burghley Park, Stamford, Luffenham Heath in Rutland, Greetham Valley (close to Stamford) and other Courses on the edge of Peterborough. -

Display PDF in Separate

5 . River Glen: River Channel Assessment - Annex C An Assessment of the Low Flow Characteristics of The River Glen, Lincolnshire September 1992 En v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & informatiom ' se r v ic e angli/ n region Kingflshaf House. Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay, herborough PE2 5ZR Prof. G Petts I Maddock Freshwater Enviroiiments Group Anglian Regional Operational Investigation 447 NRA 0 1 / 447/ 5/A So lion a! Hirers \ntbority ANNEX C AN ASSESSMENT OF THE LOW FLOW CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RIVER GLEN, LINCOLNSHIRE Undertaken for the National Rivers Authority, Anglian Region By FRESHWATER ENVIRONMENTS GROUP, INTERNATIONAL CENTRE OF LANDSCAPE ECOLOGY, LOUGHBOROUGH UNIVERSITY, LEICESTERSHIRE, LEI 1 3TU Supervised by Professor G.E. Petts Researcher: Mr. I. Maddock Environmental Agency September 1992 Thames Region Library Catalogue Ciass N o ^ . .............. ......... Accession Code.... CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF TABLES SUMMARY C l INTRODUCTION C. 2 HYDROLOGICAL DATA COLLECTION C. 3 HYDROLOGICAL RESULTS C. 3.1 Description of reaches C.3.1.1 West Glen C.3.1.2 East Glen C. 3.2 Summary of hydrological results C.4 COMPARISON OF GAINS/LOSSES BETWEEN REACHES C.4. 1 Calculation of gains/losses C.4.2 Results C.5 DETERMINATION OF THE ORIGIN OF INTRAGRAVEL WATER USING TEMPERATURE PROFILES C.5.1 Background C.5.2 Study sites C.5.3 Method C.5.4 Results and discussion C.5.5 Summary of temperature survey results C.6 REFERENCES APPENDICES A FIGURES AND TABLES ^ B TEMPERATURE SURVEY DATA f__ *. nr~~ ''.^7. "Si ! ' cis!32S3ccrc3W LIST OF FIGURES Page C. -

Monthly Water Situation Report Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire Area

Monthly water situation report Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire Area Summary – August 2021 After near average rainfall in July, August was drier than average. This saw the soil moisture deficit increase and flows in rivers decrease. The wet winter means that groundwater levels are normal or above normal and this has supported the baseflows in the groundwater fed rivers but some of the runoff dominated rivers are now classified as below normal Rainfall Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire Area received an average of 26.1mm during August, 44% of the long term average. The lowest rainfall was in the Witham to Chapel Hill hydrological area with 22.5mm, 37% of the long term average and the highest was in the Louth Grimsby and Ancholme hydrological area with 31.6mm, 52% of the long term average. Soil Moisture Deficit/Recharge In response to the dry August soil moisture deficits are either normal or above normal for the time of year. River Flows River flows have been falling during August particularly in the runoff dominated river Welland and Nene catch- ments. Flows at 8 out of the 10 sites monitored are classified as normal for August with Brampton branch of the River Nene at St Andrews Mill and the Ashley on the River Welland classified as below normal. Groundwater Levels Groundwater levels fell in line with the seasonal trend during August but because of the wetter than average win- ter recharge period these are classified as either normal or above normal for the time of year Reservoir Storage/Water Resource Zone Stocks All reservoirs are near or above their normal operating curves. -

Reflections on Some Major Lincolnshire Place-Names Part Two: Ness Wapentake to Yarborough

Reflections on some major Lincolnshire place-names Part Two: Ness wapentake to Yarborough Richard Coates This is the second half of a two-part survey, the first half of which appeared in JEPNS 40 (Coates 2008b). In contrast to the study of Lincolnshire minor names in JEPNS 39 (‘Azure Mouse, [etc.]’, Coates 2007), the focus here is on major names, defined as parish and manor names, district names in towns, and those of larger entities still. Some other names which are not conventional “minor names”, for example coastal and maritime features, are also included. The names treated appear in a single alphabetical list. The preamble to the earlier article applies to this one too, and parts of it are repeated here. Contents Introduction and apparatus 57 Typography and notation 58 A note on Scandinavian 59 Abbreviations 59 The names, treated in alphabetical order 60 Notes 95 Bibliography, references 96 Element-lists: newly-identified elements and personal names 101 Index 101 Introduction and apparatus This work is a collection of sometimes extended commentaries on names in Lincolnshire treated (i) in Kenneth Cameron’s A dictionary of Lincolnshire place-names (1998), to which, throughout, plain page-numbers in parentheses refer (e.g. 39), or (ii) in the six volumes published by November 2003 of his The place-names of Lincolnshire (PN L) which form part of the Survey of English Place-Names (1923–date), or (iii) in his article, ‘The Scandinavian 57 58 JOURNAL OF THE ENGLISH PLACE-NAME SOCIETY 41 (2009) element in minor names and field-names in north-east Lincolnshire’, published in Nomina 19 (1996). -

Gateway to the Lincolnshire Fens

The lost wilderness - Wetlands for people and wildlife and people for Wetlands - wilderness lost The Heron Introduction History & landscape Baston Fen Nature Reserve Nature Fen Baston his leaflet tells the story of a small, but important corner of a once extensive wetland years old blister to the surface of wet peaty fields; history may be discovered at each bridge which covered over 2,000 square kilometres of the East Midlands and East Anglia. and highway junction; and large gravel workings, new industrial landscapes, open and heal, change over time THalf of this area lay in the southeast Lincolnshire Fens and was said to have contained returning some of the lost wetlands to the old fen. F we were to look at a cross-section of the fenland soils, we would find at the bottom a huge areas of mire and reedswamp, great shallow lakes, meres and black pools, many Water, its control, use, quality and availability is central to the past and future of these low layer of ancient Jurassic clay covered by glacial tills and gravels, which in-turn, are overlaid wooded islands and tortuous rivers and streams. To some, this land was a sanctuary, with its lying lands: Some have lost all in their struggle with the fenland waters, washed away by floods by a lens of Lower Peat, formed between 7,500 and 5,000 years ago. Above this, a blue- abundant fisheries, wildfowl and lush summer pastures; to others it was a fearful wilderness I and storm tides; others paid dearly for their fight for freedom and the common lands. -

1St Local Transport Plan

ontents Executive Summary I-IV 1. Introduction 1 2. The Context For A Lincolnshire Local Transport Plan 3-9 2.1 Rationale 3 2.2 Key Facts About Lincolnshire 4 3. Vision, Objectives and Policy Framework 11-16 3.1 Background 11 3.2 The Vision 11 3.3 Objectives 11 3.4 The Policy Framework 12 3.5 The Transport Policy Framework For Lincolnshire 15 4. Issues and Strategic Themes 17-23 4.1 The Issues 17 4.2 The Strategic Themes 17 4.3 Developing Strategic Networks 18 4.4 Integrating Approaches in the Major Urban Areas 18 4.5 Integrating Approaches in the Large Market Towns 21 4.6 Serving the Rural Heartlands 21 4.7 Widening Travel Choices 22 4.8 Safe and Inclusive Communities and a Better Quality of Life 22 4.9 Managing Transport and Related Resources in an Efficient Way 23 5. The Strategy 25-27 5.1 From Themes to Key Strategies 25 5.2 The Key Strategies 25 5.3 Integration Between the Key Strategies 26 6. Consultation, Partnership And Cross Boundary Issues 29-32 6.1 Public Participation in The Local Transport Plan 29 6.2 Partnerships 30 6.3 Cross Boundary Working 31 7. Targets And Monitoring 33-41 7.1 Introduction to the LTP Approach 33 7.2 Developing the Indicators 33 7.3 Monitoring 39 8. Resources 43-45 8.1 Background 43 8.2 The Bid 43 9. Economy and Regeneration Schemes 47-66 9.1 Strategy for Economy and Regeneration Schemes 47 9.2 The Freight Hub 48 - Issues 48 - Transport and The Food Supply Chain 48 - The South Holland Rural Action Zone 49 - A151 Weston Bypass 49 - A1073 Spalding - Eye Improvement 51 - Boston Southern Link 54 - A52 Grantham East - West Improvement 56 9.3 Coastal Access 57 - Issues 57 - Roman Bank Quality Bus Initiative, Skegness 60 - Lumley Road Improvement Scheme, Skegness 60 - C541 Gunby/Ingoldmells Route Improvement 60 - A158/C541 Coastal Access Improvement 62 9.4 Other Economy & Regeneration Schemes 62 - Grantham Town Centre Improvement 62 - Lincoln Rail Corridor 64 - Gainsborough Waterfront 65 9.5 Longer Term Major Schemes 65 - Lincoln Eastern Bypass 65 - A17 Dualling 66 - Other Longer Term Schemes 66 10. -

Report Reference: 6

Report Reference: 8.0 Regulatory and Other Committee Open Report on behalf of Richard Wills, Executive Director (Development Services) Report to: Planning and Regulation Committee Date: 17 January 2011 Subject: Outcome of Planning Inquiry In Respect of an Appeal and Related Costs Application at West Deeping Quarry, King Street, Tallington by Lafarge Aggregates Limited Summary: This is to notify Councillors of the outcome of an appeal and related costs application heard by written representations for the importation and storage of inert waste materials and subsequent processing to form recycled aggregate for distribution into the local market. The main issue in the determination of this appeal was the effect of the proposal on highway safety. The Inspector allowed the appeal subject to 15 conditions and awarded costs against the County Council. A copy of the decision and associated cost decision is attached at Appendix A. Recommendation: That the decision of the Planning Inspectorate is noted. Discussion 1. Councillors will recall consideration of the proposal subject of this appeal at the Planning and Regulation Committee in July 2009. It was resolved that planning permission be granted subject to the applicant entering into a Section 278 agreement to fund the installation of traffic lights at the junction of King Street and the A16 and also a Section 106 Agreement relating to the prohibition of traffic visiting the site from the north or turning left out of the site. The applicant was invited to enter into these agreements and whilst agreeing to enter into the Section 106 Agreement declined to enter into the Section 278 Agreement.