Reflections on Some Major Lincolnshire Place-Names Part Two: Ness Wapentake to Yarborough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.2 North Kesteven Sites Identified Within North Kesteven Local Authority Area

Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 4.2 North Kesteven Sites identified within North Kesteven local authority area. Page 1 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 Page 2 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 North Kesteven DC SHLAA Map CL1418 Reference Site Address Land off North Street, Digby Site Area (ha) 0.31 Ward Ashby de la Launde and Cranwell Parish Digby Estimated Site 81 Capacity Site Description Greenfield site in agricultural use, within a settlement. Listed Building in close proximity. The inclusion of this site or any other sites in this document does not represent a decision by the Central Lincolnshire authorities and does not provide the site with any kind of planning status. Page 3 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 Map CL1418 http://aurora.central- lincs.org.uk/map/Aurora.svc/run?script=%5cShared+Services%5cJPU%5cJPUJS.AuroraScri pt%24&nocache=1206308816&resize=always Page 4 Central Lincolnshire Strategic Housing and Economic Land Availability Assessment SHELAA 2014 North Kesteven SHLAA Map CL432 Reference Site Address Playing field at Cranwell Road, Cranwell Site Area (ha) 0.92 Ward Ashby de la Launde and Cranwell Parish Cranwell & Byard's Leap Estimated Site 40 Capacity Site Description Site is Greenfield site. In use as open space. Planning permission refused (05/0821/FUL) for 32 dwellings. The inclusion of this site or any other sites in this document does not represent a decision by the Central Lincolnshire authorities and does not provide the site with any kind of planning status. -

Hereward and the Barony of Bourne File:///C:/Edrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/Hereward.Htm

hereward and the Barony of Bourne file:///C:/EDrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/hereward.htm Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 29 (1994), 7-10. Hereward 'the Wake' and the Barony of Bourne: a Reassessment of a Fenland Legend [1] Hereward, generally known as 'the Wake', is second only to Robin Hood in the pantheon of English heroes. From at least the early twelfth century his deeds were celebrated in Anglo-Norman aristocratic circles, and he was no doubt the subject of many a popular tale and song from an early period. [2] But throughout the Middle Ages Hereward's fame was local, being confined to the East Midlands and East Anglia. [3] It was only in the nineteenth century that the rebel became a truly national icon with the publication of Charles Kingsley novel Hereward the Wake .[4] The transformation was particularly Victorian: Hereward is portrayed as a prototype John Bull, a champion of the English nation. The assessment of historians has generally been more sober. Racial overtones have persisted in many accounts, but it has been tacitly accepted that Hereward expressed the fears and frustrations of a landed community under threat. Paradoxically, however, in the light of the nature of that community, the high social standing that the tradition has accorded him has been denied. [5] The earliest recorded notice of Hereward is the almost contemporary annal for 1071 in the D version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Northern recension probably produced at York,[6] its account of the events in the fenland are terse. It records the plunder of Peterborough in 1070 'by the men that Bishop Æthelric [late of Durham] had excommunicated because they had taken there all that he had', and the rebellion of Earls Edwin and Morcar in the following year. -

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

Grantham Ramblers 2019 Walk Programme This Programme Is for Subscription Paying Members of the Ramblers Association

Grantham Ramblers 2019 Walk Programme This programme is for subscription paying members of the Ramblers Association. Non-members are invited to try 3 walks before deciding on membership. Grantham Ramblers walk every other Sunday and Thursday on the dates shown with some additional monthly Wednesday mornings. All walks are graded moderate or leisurely. Please travel direct to the starting location leaving sufficient time to change into the necessary footwear. Please share cars if possible and people without transport should contact the leader. Park appropriately and consider other road users and local people. Stops for refreshments occur at the discretion of the leader and where suitable sites are available. Please wear clothing and footwear appropriate to the weather conditions and terrain. Dogs should be under control so as not to cause a nuisance to other walkers, general public and livestock. Dog faeces should be disposed of hygienically. All members are responsible for their own personal safety. We recommend that walkers carry a card showing details of any medication, allergies etc and a contact telephone number. The walk leader should be informed of any issues. Our telephone number on walk days only is 07551 542817. Map Date Title Description Starting location Grid Ref Time Mile Contact No Leader No 06.01.19 Good views Hough on Hill, Caythorpe Fulbeck Playing field CP 272 SK949504 10.00 8.8 01476562960 David H 10.01.19 Ancient route Pottergate, Sudbrook Ancaster church 247 SK983435 10.00 4.75 01476571322 Eileen Before the Grantham multistorey 20.01.19 bypass Little and Great Ponton, Stroxton CP 247 SK917357 10.00 9.8 01476562960 David H Denton, Denton Res, Harlaxton 24.01.19 Watch the birds Wharf, The Drift Harlaxton Bowls Club 247 SK887325 10.00 4.3 07761100298 Andy Epperstone, Main Rd, 03.02.19 Rolling Hills Epperstone Rolling Hills Cross Keys Pub. -

TRADES. [ LINCOL~E HI R.L!!

798 FAR TRADES. [ LINCOL~E HI R.l!!. FAR~IERs...,...continued. Palmer Waiter, Algarkirk,· Boston Parkin son .A1bert, 1'he Lindens, Riby. Oldershaw Jn. Hy. Swinstead, 'Bourne. Pank Hubert Edward, The Hollies, Grimsbv• Oldershaw Richd. William,Dawsmere, Postland, Crowland, Peterborough Parkinson Ardin, Barholm, Stamford Holbeach Panton Henry~ Orby, Burgh Parldnson .Arthur, Owmby vale, Oldfield Charles, Sturton, Lincoln Panton J. H. Mareham rd.Horncastl,. OwmbY,• Lincoln Oldfield J. R. Greetwell hall, Scawby Pantry Thomas, Upperthorpe, West Parkinson C. T. Slate house, Frith- Oldridge William, Amcotts, Doncaster woodside, Doncaster · villa, Boston & Boston West, Bostn Oldroyd F. Randall ho. Utterby, Louth Pape B. Silt Pit la. Wyberton, Boston Parkinson Chas. North Somercotes Oldroyd Harry Herbert, Walk farm, Pape ·Henry, Navenby, Lincoln Parkinson G.South Somercotes,Louth Great Carlton, Louth Parish J.& S. Low.Toynton,Horncastle Parkinson H. Stallingboro', Grimsby Oldroyd William, Belleau, Alford Parish George William, Twentylands, P<.~rkinson J. River head., Moortown, Olivant George, Snelland, Lincoln Hundleby, Spilsby Lincoln Olivant John Hall, Snarford, Lincoln Parish Hrbt.G. Belchford, Horncastle Parkinson J. E. H. Normanby-by- Oliver George, Holbeck, Ashby Parish P. High Toynton, Hornca.stle Stow, Gainsborough · Puerorum, Horn castle Parish Sa.ml. Mill la. Wrangle, Boston Parkinson J. H. Belchford, Horncastle Oliver George, Salmonby, Horncastle Parish T. Toynton All Saints, Spilsby Parldnson John, Eagle Barnsdale, Oliver Jesse, Grainthorpe Parish Wm. Richard, Bilsby, Alford Eagle, Lincoln Oliver John, Old Leake, Boston Park J .. Kexby grng. Kexby,Gainsboro' Parkinson John George, Fishtoft Oliver Thos.Ashby-by-Partney,Spilsby Parke George, Hougham, Grantham drove, Frithville, Boston Oliver Thomas, Benniworth, Lincoln Parker Brothers, Eagle Barnsdale, Parkinson Robert, North Somercotes Oliver T. -

New Electoral Arrangements for North Kesteven District Council Final Recommendations January 2021

New electoral arrangements for North Kesteven District Council Final Recommendations January 2021 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2021 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why North Kesteven? 2 Our proposals for North Kesteven 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Review -

Appendix 1 I.01: DEPARTMENT for TRANSPORT (DFT) ROAD INVESTMENT STRATEGY (2014) Road Investment Strategy: Overview

Appendix 1 I.01: DEPARTMENT FOR TRANSPORT (DFT) ROAD INVESTMENT STRATEGY (2014) Road Investment Strategy: Overview December 2014 Road Investment Strategy: Overview December 2014 The Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Department’s website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact the Department. Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 Website www.gov.uk/dft General enquiries https://forms.dft.gov.uk ISBN: 978-1-84864-148-8 © Crown copyright 2014 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Photographic acknowledgements Alamy: Cover Contents 3 Contents Foreword 5 The Strategic Road Network 8 The challenges 9 The Strategic Vision 10 The Investment Plan 13 The Performance Specification 22 Transforming our roads 26 Appendices: regional profiles 27 The Road Investment Strategy suite of documents (Strategic Vision, Investment Plan, Performance Specification, and this Overview) are intended to fulfil the requirements of Clause 3 of the Infrastructure Bill 2015 for the 2015/16 – 2019/20 Road Period. -

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding Neil Oliver, “History of Scotland” BBC2, 2009 “ The many armies, tens of thousands of warriors clashed at the site known as Brunanburh where the Mersey Estuary enters the sea . For decades afterwards it was simply known called the Great Battle. This was the mother of all dark-age bloodbaths and would define the shape of Britain into the modern era. Althouggg,h Athelstan emerged victorious, the resistance of the northern alliance had put an end to his dream of conquering the whole of Britain. This had been a battle for Britain, one of the most important battles in British historyyy and yet today ypp few people have even heard of it. 937 doesn’t quite have the ring of 1066 and yet Brunanburh was about much more than blood and conquest. This was a showdown between two very different ethnic identities – a Norse-Celtic alliance versus Anglo-Saxon. It aimed to settle once and for all whether Britain would be controlled by a single Imperial power or remain several separate kingdoms. A split in perceptions which, like it or not, is still with us today”. Some of the people who’ve been trying to sort it out Nic k Hig ham Pau l Cav ill Mic hae l Woo d John McNeal Dodgson 1928-1990 Plan •Background of Brunanburh • Evidence for Wirral location for the battle • If it did happen in Wirra l, w here is a like ly site for the battle • Consequences of the Battle for Wirral – and Britain Background of Brunanburh “Cherchez la Femme!” Ann Anderson (1964) The Story of Bromborough •TheThe Viking -

Lincoln in the Viking Age: a 'Town' in Context

Lincoln in the Viking Age: A 'Town' in Context Aleida Tessa Ten Harke! A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield March 2010 Volume 1 Paginated blank pages are scanned as found in original thesis No information • • • IS missing ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of Lincoln in the period c. 870-1000 AD. Traditional approaches to urban settlements often focus on chronology, and treat towns in isolation from their surrounding regions. Taking Lincoln as a case study, this PhD research, in contrast, analyses the identities of the settlement and its inhabitants from a regional perspective, focusing on the historic region of Lindsey, and places it in the context of the Scandinavian settlement. Developing an integrated and interdisciplinary approach that can be applied to datasets from different regions and time periods, this thesis analyses four categories of material culture - funerary deposits, coinage, metalwork and pottery - each of which occur in significant numbers inside and outside Lincoln. Chapter 1 summarises previous work on late Anglo-Saxon towns and introduces the approach adopted in this thesis. Chapter 2 provides a discussion of Lincoln's development during the Anglo-Saxon period, and introduces the datasets. Highlighting problems encountered during past investigations, this chapter also discusses the main methodological considerations relevant to the wide range of different categories of material culture that stand central to this thesis, which are retrieved through a combination of intrusive and non-intrusive methods under varying circumstances. Chapters 3-6 focus on funerary deposits, coinage, metalwork and pottery respectively, through analysis of distribution patterns and the impact of changes in production processes on the identity of Lincoln and its inhabitants. -

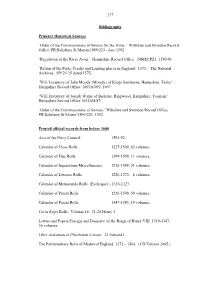

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

Seminar Stoke Rochford Hall Invite

Rural Briefing Forecasting the future for rural property Stoke Rochford Hall Tuesday 10 November at 3:00pm Seminar Schedule 15:00 Registration with tea and coffee in the Grand Hall 15:30 Johnny Dudgeon | Savills Lincoln | Chairman’s Welcome 15:35 Andrew Pearce | Savills | Rural Land Market Update 15:50 Jarred Wright | Roythornes Solicitors | Taxation Issues for We have pleasure in inviting you to our Landowners - Update Rural Briefing 16:05 Richard Garland | C. Hoare & Co. | Economic / Investment Update Forecasting the future for rural property 16:20 Break with refreshments in the Orangery To be held in the Library at Stoke Rochford Hall, 16:50 David Markham | C. Hoare & Co. | Lending Market Update Grantham,Lincolnshire NG33 5EJ 17:05 Julie Robinson | Roythornes Solicitors | Protecting Assets - What’s New Tuesday 10 November at 3:00pm 17:20 Kirsty Lemond | Savills | Residential Market Update RSVP by 28 October 2015 17:40 Questions Georgie Parker 01522 508949 17:55 Chairman’s Closing Remarks [email protected] Savills Lincoln Olympic House 18:00 Close Doddington Road, Lincoln LN6 3SE Seminar Directions Travelling by car - A1 from the south Lincoln Horncastle We are situated on the left, two and a half miles A1 from north of the A151 junction at Colsterworth. The the North village of Stoke Rochford is signposted from the ▼ A1. Having left the A1, after a quarter of a mile turn right into the Stoke Rochford Hall grounds Newark and follow the road up to the Hall. on Trent Sleaford Travelling by car - A1 from the north We are on the right, two miles south of the A1 village of Great Ponton. -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies.