Ultimate-Antarctica-2013-Logbook 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Falkland Islands & Antarctic Peninsula Discovery

FALKLAND ISLANDS & ANTARCTIC PENINSULA DISCOVERY ABOARD THE OCEAN ENDEAVOUR Set sail aboard the comfortable and spacious polar expedition vessel, the Ocean Endeavour, to discover the raw beauty of the untamed Falkland Islands and Antarctica on a 19 day voyage. Starting in Buenos Aires, giving you the chance to explore this buzzing Latin America city before embarking your vessel and heading for the ruggedly beautiful Falkland Islands. A stop in Ushuaia en route to Antarctica allows a day of exploration of Tierra del Fuego National Park. Enter into a world of ice, surrounded by the spellbindingly beautiful landscapes created by the harsh Antarctic climate. This is a journey of unspoiled wilderness you’ll never forget DEPARTS: 27 OCT 2020 DURATION: 19 DAYS Highlights and inclusions: Explore the amazing city of Buenos Aires. A day of exploration of Tierra del Fuego National Park, as we get off the beaten track with our expert guide Experience the White Continent and encounter an incredible variety of wildlife. Take in the Sub-Antarctic South Shetland Islands and the spectacular Antarctic Peninsula. Discover the top wildlife destination in the world where you can see penguins, seals, whales and albatrosses. Admire breathtaking scenery such as icebergs, glaciated mountains and volcanoes. Enjoy regular zodiac excursions and on-shore landings. Benefit from a variety of on-board activities including educational lectures on the history, geology and ecology by the expedition team. Enjoy the amenities on board including expedition lounge, restaurant, bar, pool, jacuzzi, library, gym, sun deck, spa facilities and sauna. Your cruise is full-board including breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks. -

Antarctica, South Georgia & the Falkland Islands

Antarctica, South Georgia & the Falkland Islands January 5 - 26, 2017 ARGENTINA Saunders Island Fortuna Bay Steeple Jason Island Stromness Bay Grytviken Tierra del Fuego FALKLAND SOUTH Gold Harbour ISLANDS GEORGIA CHILE SCOTIA SEA Drygalski Fjord Ushuaia Elephant Island DRAKE Livingston Island Deception PASSAGE Island LEMAIRE CHANNEL Cuverville Island ANTARCTIC PENINSULA Friday & Saturday, January 6 & 7, 2017 Ushuaia, Argentina / Beagle Channel / Embark Ocean Diamond Ushuaia, ‘Fin del Mundo,’ at the southernmost tip of Argentina was where we gathered for the start of our Antarctic adventure, and after a night’s rest, we set out on various excursions to explore the neighborhood of the end of the world. The keen birders were the first away, on their mission to the Tierra del Fuego National Park in search of the Magellanic woodpecker. They were rewarded with sightings of both male and female woodpeckers, Andean condors, flocks of Austral parakeets, and a wonderful view of an Austral pygmy owl, as well as a wide variety of other birds to check off their lists. The majority of our group went off on a catamaran tour of the Beagle Channel, where we saw South American sea lions on offshore islands before sailing on to the national park for a walk along the shore and an enjoyable Argentinian BBQ lunch. Others chose to hike in the deciduous beech forests of Reserva Natural Cerro Alarkén around the Arakur Resort & Spa. After only a few minutes of hiking, we saw an Andean condor soar above us and watched as a stunning red and black Magellanic woodpecker flew towards us and perched on the trunk of a nearby tree. -

15-16 April No. 3

VOLUME 15-16 APRIL NO. 3 HONORARY PRESIDENT “BY AND FOR ALL ANTARCTICANS” Dr. Robert H. Rutford Post Office Box 325, Port Clyde, Maine 04855 PRESIDENT www.antarctican.org Dr. Anthony J. Gow www.facebook.com/antarcticansociety 117 Poverty Lane Lebanon, NH 03766 [email protected] Looking back .................................... 1 Stowaway in Antarctica ................... 9 VICE PRESIDENT First winter at 90 South ..................... 2 Ponies and dogs commemorated ….11 Liesl Schernthanner P.O. Box 3307 A teacher’s experience, 16 yrs later .. 4 Henry Worsley’s ending goal ......... 12 Ketchum, ID 83340 [email protected] Antarctic poem my heartfelt tribute .. 5 Correction: Jorgensen obituary ....... 12 TREASURER 1950s South Georgia Survey ............ 7 Gathering in Maine UPDATE! ... 12 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple Box 325 Port Clyde, ME 04855 LOOKING BACK FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF TODAY Phone: (207) 372-6523 [email protected] Decades after returning to lives in lower latitudes, four veterans in this SECRETARY issue describe their Antarctic sojourns from a modern perspective. Cliff Joan Boothe o 2435 Divisadero Drive Dickey, near the end of that first winter at 90 S in 1957, “knew then that the San Francisco, CA 94115 United States would never leave the South Pole.” Teacher Joanna Hubbard, [email protected] 16 years after a season at Palmer Station, says the experience “likely set the WEBMASTER stage to keep me in education for the long haul.” Thomas Henderson Attorney Jim Porter, with 84 months on the Ice including four winters, 520 Normanskill Place Slingerlands, NY 12159 says, “I appreciate the inquiry about tying my Antarctic past to my federal [email protected] present, but it’s no use. -

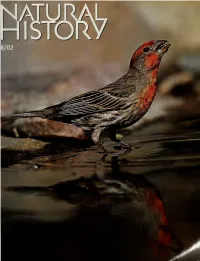

AMNH Digital Library

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Antarctic Express

ANTARCTIC 2021.22 ANTARCTIC EXPRESS Crossing the Circle Contents 1 Overview 2 Itinerary 5 Arrival and Departure Details 8 Your Ship Options 10 Included Activities 11 Adventure Options 12 Dates and Rates 13 Inclusions and Exclusions 14 Your Expedition Team 15 Extend Your Trip 16 Meals on Board 17 Possible Excursions 21 Packing Checklist Overview Antarctic Express: Crossing the Circle Antarctica offers so many extraordinary things to see and do, and traveling with Quark Expeditions® offers multiple options to personalize your experience. We’ve designed this guide to help you identify what interests you most, so that you can start planning your version of the perfect expedition to the 7th Continent. Check off a travel milestone by crossing the Antarctic Circle. Maximize your adventure by skipping the ocean transit and flying over the Drake Passage by charter plane. Simply combine our exciting Crossing the Circle: Southern Expedition EXPEDITION IN BRIEF itinerary with a direct round-trip flight from Chile to your polar-ready ship, to get Fly over the Drake Passage and experience the fastest, most direct our Antarctic Express: Crossing the Circle voyage. Then, explore the wonders of the way to Antarctica Antarctic Peninsula by sea, and continue further to reach 66⁰33´ south. Check other Witness iconic Antarctic wildlife, such as penguins, seals and whales achievements off your bucket list as well, such as sea kayaking through channels Marvel at Antarctic Peninsula dotted with icebergs. highlights, including crossing the Antarctic Circle Antarctica has been inspiring explorers for centuries and our expeditions offer the Celebrate crossing the chance for you to discover why. -

Saint Louis Zoo Library

Saint Louis Zoo Library and Teacher Resource Center MATERIALS AVAILABLE FOR LOAN DVDs and Videocassettes The following items are available to teachers in the St. Louis area. DVDs and videos must be picked up and returned in person and are available for a loan period of one week. Please call 781-0900, ext. 4555 to reserve materials or to make an appointment. ALL ABOUT BEHAVIOR & COMMUNICATION (Animal Life for Children/Schlessinger Media, DVD, 23 AFRICA'S ANIMAL OASIS (National Geographic, 60 min.) Explore instinctive and learned behaviors of the min.) Wildebeest, zebras, flamingoes, lions, elephants, animal kingdom. Also discover the many ways animals rhinos and hippos are some animals shown in Tanzania's communicate with each other, from a kitten’s meow to the Ngorongoro Crater. Recommended for grade 7 to adult. dances of bees. Recommended for grades K to 4. ALL ABOUT BIRDS (Animal Life for AFRICAN WILDLIFE (National Geographic, 60 min.) Children/Schlessinger Media, DVD, 23 min.) Almost 9,000 Filmed in Namibia's Etosha National Park, see close-ups of species of birds inhabit the Earth today. In this video, animal behavior. A zebra mother protecting her young from explore the special characteristics they all share, from the a cheetah and a springbok alerting his herd to a predator's penguins of Antarctica to the ostriches of Africa. presence are seen. Recommended for grade 7 to adult. Recommended for grades K to 4. ALL ABOUT BUGS (Animal Life for ALEJANDRO’S GIFT (Reading Rainbow, DVD .) This Children/Schlessinger Media, DVD, 23 min.) Learn about video examines the importance of water; First, an many different types of bugs, including the characteristics exploration of the desert and the animals that dwell there; they have in common and the special roles they play in the then, by taking an up close look at Niagara Falls. -

Operational Plan for the Eradication of Rodents from South Georgia: Phase 1

1 Operational Plan for the eradication of rodents from South Georgia: Phase 1 South Georgia Heritage Trust 21 December 2010 Rodent eradication on South Georgia, Phase 1: Operational Plan, version 4. 21 Dec 2010 2 Table of Contents RELATED DOCUMENTS .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................... 4 NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 5 Background .................................................................................................................................................... 5 This project..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Eradication methodology & timing ................................................................................................................ 6 Project management & staffing ...................................................................................................................... 8 Risk management............................................................................................................................................ 8 Project and Operational Plan development .................................................................................................. -

Antarctica School Units for Levels 3, 4 &5

PCAS 18 (2015/2016) Supervised Project Report (ANTA604) Antarctica School Units for Levels 3, 4 &5 Jo Eason Student ID: 78595774 Word count: 8,036 Abstract (ca. 200 words): There are three topics developed for primary age pupils, Antarctica and Gondwanaland, The Antarctic Food Web and Living in the Extreme Environment of Antarctica. Each unit has four sections; an introductory section of information, some suggestions for questions and discussion, pen and paper activities and practical work. Several websites are suggested as resources for teachers. Each topic has two units, one aimed at Level 3 & 4 and the other for Level 5. The Achievement Aims for each unit are listed in the contents page at the beginning of this report. The Nature of Science is also considered as the units develop scientific thinking with the activities, research and experiments suggested. These units could be taught as stand-alone units or within a study of Antarctica over a longer period. These resources are Educational resources for teachers to deliver Antarctic–focused lessons. A further step is to share these lessons with other teachers and to run a workshop for teachers wanting to teach about Antarctica. This would be a collaboration with Antarctica NZ and involve promoting Learnz, the interactive field trip site. Antarctic Units Contents Gondwanaland and the Geological history of Antarctica Level 3 & 4, Level 5 Making sense of Planet Earth and Beyond Achievement Objective • Investigate the geological history of planet Earth and understand that our planet has a long past and has undergone many changes. • Appreciate that science is a way of explaining the world and that science knowledge changes over time. -

South Georgia Andrew Clarke, John P

Important Bird Areas South Georgia Andrew Clarke, John P. Croxall, Sally Poncet, Anthony R. Martin and Robert Burton n o s r a e P e c u r B South Georgia from the sea; a typical first view of the island. Abstract The mountainous island of South Georgia, situated in the cold but productive waters of the Southern Ocean, is a UK Overseas Territory and one of the world’s most important seabird islands. It is estimated that over 100 million seabirds are based there, while there may have been an order of magnitude more before the introduction of rats. South Georgia has 29 species of breeding bird, and is the world’s most important breeding site for six species (Macaroni Penguin Eudyptes chrysolophus , Grey-headed Albatross Thalassarche chrysostoma , Northern Giant Petrel Macronectes halli , Antarctic Prion Pachyptila desolata , White-chinned Petrel Procellaria aequinoctialis and Common Diving Petrel Pelecanoides urinatrix ). Several of the key species are globally threatened or near-threatened, which emphasises the need for action to improve the conservation status of the island’s birds. South Georgia is currently classified by BirdLife International as a single Important Bird Area (IBA) but it may be better considered as comprising several distinct IBAs. Current threats to the South Georgia avifauna include rats (a major campaign to eliminate rats began in 2010/11), regional climate change, and incidental mortality in longline and trawl fisheries. Local fisheries are now well regulated but South Georgia albatrosses and petrels are still killed in large numbers in more distant fisheries. 118 © British Birds 105 • March 2012 • 118 –144 South Georgia This paper is dedicated to the memory of Peter Prince (1948–1998), who worked on South Georgia from 1971. -

Serengeti of the Southern Ocean

SOUTH GEORGIA & THE FALKLANDS SERENGETI OF THE SOUTHERN OCEAN ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPLORER | 2017-2019 TM If the astonishing sight of some 100,000+ king penguins in one rookery alone were all this expedition offered; if at the end of our time among the kings—observing, listening, photographing, walking among and communing with them—our team said “Show’s over, Folks,” and everyone were to head back home—it’s likely no one would complain, according to all our expedition leaders. It’s that profound and rewarding an experience. BUT THERE’S MORE: THE GREATEST WILDLIFE SPECTACLE ON EARTH. There’s life in such profusion that it boggles your mind as it sends your spirit soaring. Dense colonies of king penguins, fur seals, elephant seals, macaroni and gentoo penguins. Slopes of stunning windward cliffs teeming with grey-headed, black-browed and wandering albatross— nearly a third of all the birds of this species nest here. Plus, there are the rare endemics: the mighty South Georgia pipit, the only songbird in the Antarctic region and South Georgia’s only passerine; and the Falkland’s Johnny rook. (Life-listers take note.) Once a killing ground for whalers, South Georgia is now a sanctuary, an extravagant celebration of wildlife and pristine wildness. We travel with some of the best wildlife photographers on Earth, and even their best photos can’t do this spectacle justice. So, we offer images on the following pages as an invitation—to see it all yourself. TM Cover photo: King penguins in the surf. ©Michael S. Nolan. Ship’s registry: Bahamas The thrilling sight of tens of thousands of king penguins greeting you on a single beach in South Georgia! Dear Traveler, Every single person I’ve ever met who’s been to South Georgia—our guests, our staff, our captains—all say, essentially, the same thing. -

A Spring Expedition to the Sub-Antarctic

SOUTH GEORGIA EXPEDITION 2018 Stephen Venables in association with Pelagic Expeditions A spring expedition to the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia September 8 – October 13 2018 Sailing, wildlife and polar heritage Ski-mountaineering with the possibility of first ascents !1 SOUTH GEORGIA EXPEDITION 2018 Stephen Venables in association with Pelagic Expeditions BACKGROUND I first went to South Georgia during the austral summer of 1989-90. At the end of that expedition, when we made first ascents of Mt Kling and Mt Carse, I assumed that this was a one-off trip. How wrong I was. I have now been back six times and each time I leave the island I am even keener to return to that magical combination of ocean, glaciers and mountains, inhabited by some of the most prolific wildlife anywhere in the world. Three of my seven expeditions have been to the Salvesen Range at the little-visited southern end of the island. The most recent, in 2016, achieved several first ascents, including the spectacular Starbuck Peak. However, there is still unfinished business. Several stunning peaks remain unclimbed; regardless of summits, the route we perfected from Trolhul, at the southern tip of the island, to the immense penguin colony at St Andrew’s Bay, is a magnificent ski tour. That is our Plan A for 2018. If conditions are unsuitable, Plan B is to explore the more accessible – and slightly less weather-dependent – northwest end of the island. As usual, we also plan many other delights for the non-mountaineering sailing support team. ANTARCTICA FALKLANDS Shackleton 1916 Allardyce Range 100 miles N Salvesen !2 SOUTH GEORGIA EXPEDITION 2018 Stephen Venables in association with Pelagic Expeditions EXPEDITION LEADERS The 2018 expedition, like four previous ventures, will be led by me and the owner of the Pelagic fleet, Skip Novak, who has been sailing to remote mountains in and around Antarctica for over 25 years.