Antarctic Biosecurity Syndicate Project, GCAS 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Falkland Islands & Antarctic Peninsula Discovery

FALKLAND ISLANDS & ANTARCTIC PENINSULA DISCOVERY ABOARD THE OCEAN ENDEAVOUR Set sail aboard the comfortable and spacious polar expedition vessel, the Ocean Endeavour, to discover the raw beauty of the untamed Falkland Islands and Antarctica on a 19 day voyage. Starting in Buenos Aires, giving you the chance to explore this buzzing Latin America city before embarking your vessel and heading for the ruggedly beautiful Falkland Islands. A stop in Ushuaia en route to Antarctica allows a day of exploration of Tierra del Fuego National Park. Enter into a world of ice, surrounded by the spellbindingly beautiful landscapes created by the harsh Antarctic climate. This is a journey of unspoiled wilderness you’ll never forget DEPARTS: 27 OCT 2020 DURATION: 19 DAYS Highlights and inclusions: Explore the amazing city of Buenos Aires. A day of exploration of Tierra del Fuego National Park, as we get off the beaten track with our expert guide Experience the White Continent and encounter an incredible variety of wildlife. Take in the Sub-Antarctic South Shetland Islands and the spectacular Antarctic Peninsula. Discover the top wildlife destination in the world where you can see penguins, seals, whales and albatrosses. Admire breathtaking scenery such as icebergs, glaciated mountains and volcanoes. Enjoy regular zodiac excursions and on-shore landings. Benefit from a variety of on-board activities including educational lectures on the history, geology and ecology by the expedition team. Enjoy the amenities on board including expedition lounge, restaurant, bar, pool, jacuzzi, library, gym, sun deck, spa facilities and sauna. Your cruise is full-board including breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks. -

AMNH Digital Library

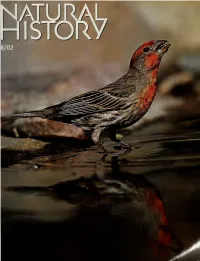

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

Antarctic Express

ANTARCTIC 2021.22 ANTARCTIC EXPRESS Crossing the Circle Contents 1 Overview 2 Itinerary 5 Arrival and Departure Details 8 Your Ship Options 10 Included Activities 11 Adventure Options 12 Dates and Rates 13 Inclusions and Exclusions 14 Your Expedition Team 15 Extend Your Trip 16 Meals on Board 17 Possible Excursions 21 Packing Checklist Overview Antarctic Express: Crossing the Circle Antarctica offers so many extraordinary things to see and do, and traveling with Quark Expeditions® offers multiple options to personalize your experience. We’ve designed this guide to help you identify what interests you most, so that you can start planning your version of the perfect expedition to the 7th Continent. Check off a travel milestone by crossing the Antarctic Circle. Maximize your adventure by skipping the ocean transit and flying over the Drake Passage by charter plane. Simply combine our exciting Crossing the Circle: Southern Expedition EXPEDITION IN BRIEF itinerary with a direct round-trip flight from Chile to your polar-ready ship, to get Fly over the Drake Passage and experience the fastest, most direct our Antarctic Express: Crossing the Circle voyage. Then, explore the wonders of the way to Antarctica Antarctic Peninsula by sea, and continue further to reach 66⁰33´ south. Check other Witness iconic Antarctic wildlife, such as penguins, seals and whales achievements off your bucket list as well, such as sea kayaking through channels Marvel at Antarctic Peninsula dotted with icebergs. highlights, including crossing the Antarctic Circle Antarctica has been inspiring explorers for centuries and our expeditions offer the Celebrate crossing the chance for you to discover why. -

Saint Louis Zoo Library

Saint Louis Zoo Library and Teacher Resource Center MATERIALS AVAILABLE FOR LOAN DVDs and Videocassettes The following items are available to teachers in the St. Louis area. DVDs and videos must be picked up and returned in person and are available for a loan period of one week. Please call 781-0900, ext. 4555 to reserve materials or to make an appointment. ALL ABOUT BEHAVIOR & COMMUNICATION (Animal Life for Children/Schlessinger Media, DVD, 23 AFRICA'S ANIMAL OASIS (National Geographic, 60 min.) Explore instinctive and learned behaviors of the min.) Wildebeest, zebras, flamingoes, lions, elephants, animal kingdom. Also discover the many ways animals rhinos and hippos are some animals shown in Tanzania's communicate with each other, from a kitten’s meow to the Ngorongoro Crater. Recommended for grade 7 to adult. dances of bees. Recommended for grades K to 4. ALL ABOUT BIRDS (Animal Life for AFRICAN WILDLIFE (National Geographic, 60 min.) Children/Schlessinger Media, DVD, 23 min.) Almost 9,000 Filmed in Namibia's Etosha National Park, see close-ups of species of birds inhabit the Earth today. In this video, animal behavior. A zebra mother protecting her young from explore the special characteristics they all share, from the a cheetah and a springbok alerting his herd to a predator's penguins of Antarctica to the ostriches of Africa. presence are seen. Recommended for grade 7 to adult. Recommended for grades K to 4. ALL ABOUT BUGS (Animal Life for ALEJANDRO’S GIFT (Reading Rainbow, DVD .) This Children/Schlessinger Media, DVD, 23 min.) Learn about video examines the importance of water; First, an many different types of bugs, including the characteristics exploration of the desert and the animals that dwell there; they have in common and the special roles they play in the then, by taking an up close look at Niagara Falls. -

Antarctica School Units for Levels 3, 4 &5

PCAS 18 (2015/2016) Supervised Project Report (ANTA604) Antarctica School Units for Levels 3, 4 &5 Jo Eason Student ID: 78595774 Word count: 8,036 Abstract (ca. 200 words): There are three topics developed for primary age pupils, Antarctica and Gondwanaland, The Antarctic Food Web and Living in the Extreme Environment of Antarctica. Each unit has four sections; an introductory section of information, some suggestions for questions and discussion, pen and paper activities and practical work. Several websites are suggested as resources for teachers. Each topic has two units, one aimed at Level 3 & 4 and the other for Level 5. The Achievement Aims for each unit are listed in the contents page at the beginning of this report. The Nature of Science is also considered as the units develop scientific thinking with the activities, research and experiments suggested. These units could be taught as stand-alone units or within a study of Antarctica over a longer period. These resources are Educational resources for teachers to deliver Antarctic–focused lessons. A further step is to share these lessons with other teachers and to run a workshop for teachers wanting to teach about Antarctica. This would be a collaboration with Antarctica NZ and involve promoting Learnz, the interactive field trip site. Antarctic Units Contents Gondwanaland and the Geological history of Antarctica Level 3 & 4, Level 5 Making sense of Planet Earth and Beyond Achievement Objective • Investigate the geological history of planet Earth and understand that our planet has a long past and has undergone many changes. • Appreciate that science is a way of explaining the world and that science knowledge changes over time. -

Historical Basis of Binomials Assigned to Helminths Collected on Scott's Last Antarctic Expedition

J. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 61(1), 1994, pp. 1-11 Historical Basis of Binomials Assigned to Helminths Collected on Scott's Last Antarctic Expedition WILLIAM C. CAMPBELL' AND ROBIN M. OvERSTREET2 1 The Charles A. Dana Research Institute for Scientists Emeriti, Drew University, Madison, New Jersey 07940 and 2 Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, Ocean Springs, Mississippi 39564 ABSTRACT: Scientific investigations were a feature of Captain R. F. Scott's ill-fated expedition to the South Pole in 1910-1912. Among them was a study of parasitic worms in the coastal wildlife of Antarctica. It was the special project of Surgeon Edward L. Atkinson, whose scientific contributions, like his passion for high adventure, have largely been forgotten. The new parasitic species that he discovered were given names that were intended to honor the Expedition and many of its members. However, it was not then usual for new species descriptions to include an explanation of the proposed new binomials, and the significance of these particular names is not obvious to modern readers. This article examines the historical connection between the names of Atkinson's worms and the individuals and exploits commemorated by those names. KEY WORDS: Antarctica, helminths, history, marine parasites. One way or another, parasites and parasitol- which are extant and have been described ogists have been a feature of several Arctic and (Campbell, 1991). Parasites were examined mi- Antarctic expeditions, and the association be- croscopically, but apparently cursorily, in Ant- tween poles and parasites is particularly strong arctica and were preserved for later study. in the case of Captain Scott's famous and fatal Description of the parasites was subsequently Terra Nova Expedition to the South Pole. -

Antarctica Free

FREE ANTARCTICA PDF Lucy Bowman,Adam Stower | 32 pages | 29 Jun 2007 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9780746080351 | English | London, United Kingdom Antarctica - News and Scientific Articles on Live Science There is no mobile phone service. There are no ATMs, no souvenir stores, and no tourist traps. Antarctica is nearly twice the size of Australia Antarctica mostly covered with a thick sheet of ice. Lars-Eric Lindblad first took a group of 57 visitors to Antarctica Antarctica There were no satellite ice charts. You were not that Antarctica navigationally from the early explorers. Even now it can be hard to really understand a place like Antarctica. It is the coldest, windiest, and driest place on earth. It has no currency of its own. It is a Antarctica with no trees, no bushes, and no long-term residents. More meteorites are found in Antarctica than any other place Antarctica the world. Antarctica Antarctic travel season lasts from November through March, the Antarctic summer. Temperatures can range from around 20 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Antarctica best time for penguin spotting is late December or early January. Wait Antarctica long and previously pristine penguin colonies Antarctica dirty and smelly, said Nik Horncastle, a regional specialist with Audley Travel. For peak whale watching, try February or March. Other activities including snowshoeing, kayaking, skiing, camping, snorkeling, diving, and visits to historic sites from earlier expeditions can be experienced throughout the Antarctica. One of the more common routes to Antarctica is by ship via Ushuaia, a city at the southern tip of Argentina. On board, expect to mingle with scientists, naturalists, historians, and underwater specialists. -

Frozen31515.Pdf

Aurora Australis (Southern Lights) Life in a Frozen World-INTERIOR.indd 2-3 3/20/20 1:20 PM LIFE IN A FROZEN WORLD Life in a Frozen World-INTERIOR.indd 4-1 3/20/20 1:21 PM To the global community of Antarctic scientists and to the schoolchildren around the world who are demanding that their governments take action against climate change —M. B. LIFE IN A FROZEN WORLD To all researchers who work to better understand Wildlife of Antarctica the complexities of nature, especially in such a harsh environment as Antarctica. And to my awesome wife Noni and our amazing daughter Nina, heartfelt thanks for listening as I described all the wonders I discovered about Antarctica during my research for the book —T. G. Written by Mary Batten Illustrated by Thomas Gonzalez Published by Edited by Vicky Holifield Peachtree Publishing Company Inc. Design and composition by Nicola Simmonds Carmack 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue and Adela Pons Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 Illustrations created in pastel, colored pencils, www.peachtree-online.com and airbrush. Text © 2020 by Mary Batten Printed in February by Toppan Leefung Ltd Illustrations © 2020 by Thomas Gonzalez 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, ISBN 978-1-68263-151-5 stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the Library of Congress. -

Diseases Workshop ANTDIV98

.2 DISEASES OF ANTARCTIC WILDLIFE A Report on the “Workshop on Diseases of Antarctic Wildlife” hosted by the Australian Antarctic Division August 1998 Prepared by Knowles Kerry, Martin Riddle (Convenors) and Judy Clarke Australian Antarctic Division, Channel Highway, Kingston, 7050, Australia E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY........................................................................................... VI GLOSSARY.................................................................................................................. VI 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................ 1 1.1 INFORMATION PAPER AT ATCM XXI................................................................ 1 1.2 ORGANISATION OF THE WORKSHOP.................................................................... 1 1.3 WORKSHOP ON DISEASES OF ANTARCTIC WILDLIFE.......................................... 1 1.4 WORKING GROUP SESSIONS............................................................................... 2 1.5 PRESENTATION OF REPORT TO ATCM XXIII.................................................... 2 2.0 DISEASE IN ANTARCTICA: SUPPORTING INFORMATION...................... 5 2.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 5 2.2 ISOLATION OF ANTARCTIC WILDLIFE................................................................. 5 2.3 THE ANTARCTIC -

Recognizing Achievements, Celebrating Success Appendix A

Tides of Change Across the Gulf : Chapter 7 - Recognizing Achievements, Celebrating Success Appendix A - Background Information on Groups Table of Contents Massachusetts Page Essex County Greenbelt Association Inc. .. 1 Massachusetts Bays Monitoring Program. .. 3 Massachusetts Bay Monitoring Program . 6 Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) . .7 New England Aquarium Diver Club . 8 Tufts Centre for Conservation Medicine . .9 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution . .11 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution . 15 Maine Bagaduce Watershed Association . .21 Blue Hill Heritage Trust . 22 Casco Bay Estuary Project . 23 Cove Brook Watershed Council/8 Rivers Roundtable . 26 Damariscotta River Association . 27 Downeast Salmon Federation . .29 East Penobscot Bay Environmental Alliance . 31 FairPlay for Harpswell . 32 Friends of Acadia. 34 Friends of Taunton Bay . 35 Georges River Tidewater Association . 37 Island Institute . 39 Marine Environmental Research Institute (MERI)] . 41 Maine Sea Grant/Cooperative Extension marine Extension Team . 48 Quoddy Regional Land Trust . 51 Sheepscot Valley Conservation Association . 53 The Chewonki Foundation . 54 The Lobster Conservancy . .. 56 The Maine Chapter of The Nature Conservancy . 59 The Ocean Conservancy-New England Regional Office . 60 Union River Watershed Coalition. .. .62 University of Southern Maine . 63 Vinalhaven Land Trust . 64 Wells NERR Coastal Training Program . 66 New Hampshire Centre for Coastal and Ocean Mapping B University of New Hampshire . 67 Coastal Conservation Association of NH . 68 Nova Scotia Acadia Centre for Estuarine Research . .69 Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership . 71 Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership/Minas Basin Working Group. 73 Bedford Institute of Oceanography . 75 Centre for Water Resources Studies, Dalhousie University . 76 Clean Annapolis River Project . 77 Dr. Arthur Hines School . -

Resources COSEE-West Ecological Responses of Antarctic Krill

Resources COSEE-West Ecological Responses of Antarctic Krill WEBSITES AUD = includes audio, VID = includes video, ANI = animation Our Speakers for Wednesday, March 21 & Saturday, March 24, 2007 Dr. Robin Ross, UCSB http://passporttoknowledge.com/scic/foodwebs/researchers/robinross_bio1.html She participates in the Palmer LTER (Long Term Ecological Research) http://pal.lternet.edu/ Dr. William Hamner, Professor Emeritus, UCLA http://www.eeb.ucla.edu/indivfaculty.php?FacultyKey=695 Krill National Geographic: Krill Profile Page (including photos of animals that are dependent on krill) http://www3.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/krill.html National Geographic: Krill Swarm Seas by the Billions VID http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/09/060921-krill-video.html National Geographic: Scientists Discover Mystery Krill Killer, July 2003 http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/07/0717_030717_krillkiller.html National Geographic: Tiny Krill Key to Ocean Turbulence, Sept 2006 http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/09/060921-krill-turbulence.html Earthwatch Radio AUD Krill Conservation http://ewradio.org/program.aspx?ProgramID=3939 Melting Ice and Lost Meals http://ewradio.org/program.aspx?ProgramID=3929 Antarctic Explorers – Teachers Experiencing Antarctica and the Arctic (TEA) http://tea.armadaproject.org/cowles/2.17.2002.html Antarctica National Geographic: Antarctica Information and History http://www3.nationalgeographic.com/places/continents/continent_antarctica.html Antarctica, Biological Sciences Santa Barbara -

EPIC ANTARCTICA: from the PENINSULA to the ROSS SEA & BEYOND Current Route: Ushuaia, Argentina to Dunedin, New Zealand

EPIC ANTARCTICA: FROM THE PENINSULA TO THE ROSS SEA & BEYOND Current route: Ushuaia, Argentina to Dunedin, New Zealand 35 Days National Geographic Endurance 126 Guests Expeditions in: Jan/Dec From $49,990 to $105,990 * This extraordinary new voyage is like a blockbuster film—the star is the seventh continent. And the co-stars are the big ice of remote West Antarctica, where we are sure to set foot where no other humans ever have; the prolific wildlife and impressive ice shelf of the Ross Sea region; and the sub-Antarctic islands of New Zealand and Australia, World Heritage sites for the thousands of seals and millions of penguins here, including huge colonies of king penguins and the endemic royal penguin. This is wildness and wildlife at its finest. Following in the footsteps of Scott, Ross, Amundsen and Shackleton, perhaps only a few thousand people in the history of the planet have ever made this voyage. And the opportunity we’re offering is too good to pass up. Two departures only. Call us at 1.800.397.3348 or call your Travel Agent. In Australia, call 1300.361.012 • www.expeditions.com DAY 1: Buenos Aires, Argentina padding Arrive in Buenos Aires. Settle into the Alvear Icon 2021 Departure Dates: Hotel (or similar) before seeing the city’s Beaux- Arts palaces and the famous balcony associated 28 Dec with Eva Peron. 2022 Departure Dates: 28 Jan 29 Dec DAY 2: Fly to Ushuaia/Embark padding Fly by private charter to Ushuaia, the 2023 Departure Dates: southernmost city in the world.