Analysis of the Myths, Photographs and Laws in China Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Malouf's Remembering Babylon and the Wild Man of the European Cultural Consciousness

Volume 27, number 1, May 2000 Sathyabhama Daly DAVID MALOUF'S REMEMBERING BABYLON AND THE WILD MAN OF THE EUROPEAN CULTURAL CONSCIOUSNESS David Malouf's Remembering Babylon engages with both the myth of the wild man of the Western literary tradition and with Judaeo-Christian concept of the wilderness. In doing so, it illustrates the way in which these myths exert a powerful influence on the European settlers' conception of the Australian landscape and its indigenous people. The myth of the wild man itself recurs throughout the history of Western literature. His presence, according to Richard Bernheimer in Wild Men in the Middle Ages, dates back to the pre-Christian world and to the pagan beliefs of native religions which the Church found difficult to eradicate (21). The image which has persisted in Western art and literature is that of the wild man as a degenerate being—an insane creature who, robbed of the power of speech and intellect, wanders alone in the wilderness. He is inextricably linked with the environment he inhabits, to the point where wildness and insanity almost become inseparable terms (Bernheimer 12).1 These characteristics call to mind Gemmy Fuirley in Remembering Babylon, a simple-minded, strange "white black man" (69), an outcast of white society, who is discovered by the Aborigines and raised as one of them. A hybrid figure, he is interjected into history—from nature into culture, as it were—in order to confront the white settlers with their repression of the Aboriginal presence, as well as to provoke them into a fuller understanding of themselves. -

Monk Seals in Post-Classical History

Monk Seals in Post-Classical History The role of the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) in European history and culture, from the fall of Rome to the 20th century William M. Johnson Mededelingen No. 39 2004 NEDERLANDSCHE COMMISSIE VOOR INTERNATIONALE NATUURBESCHERMING Mededelingen No. 39 i NEDERLANDSCHE COMMISSIE VOOR INTERNATIONALE NATUURBESCHERMING Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection Secretariaat: Dr. H.P. Nooteboom National Herbarium of the Netherlands Rijksuniversiteit Leiden Einsteinweg 2 Postbus 9514, 2300 RA Leiden Mededelingen No. 39, 2004 Editor: Dr. H.P. Nooteboom PDF edition 2008: Matthias Schnellmann Copyright © 2004 by William M. Johnson ii MONK SEALS IN POST-CLASSICAL HISTORY The role of the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) in European history and culture, from the fall of Rome to the 20th century by William M. Johnson Editor, The Monachus Guardian www.monachus-guardian.org email: [email protected] iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS MONK SEALS IN POST-CLASSICAL HISTORY ......................................................III ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... VII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ VII MONK SEALS IN POST-CLASSICAL HISTORY ..............................................................................1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SPECIES ......................................................................1 -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

Clifford-Ishi's Story

ISHI’S STORY From: James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the 21st Century. (Harvard University Press 2013, pp. 91-191) Pre-publication version. [Frontispiece: Drawing by L. Frank, used courtesy of the artist. A self-described “decolonizationist” L. Frank traces her ancestry to the Ajachmem/Tongva tribes of Southern California. She is active in organizations dedicated to the preservation and renewal of California’s indigenous cultures. Her paintings and drawings have been exhibited world wide and her coyote drawings from News from Native California are collected in Acorn Soup, published in 1998 by Heyday Press. Like coyote, L. Frank sometimes writes backwards.] 2 Chapter 4 Ishi’s Story "Ishi's Story" could mean “the story of Ishi,” recounted by a historian or some other authority who gathers together what is known with the goal of forming a coherent, definitive picture. No such perspective is available to us, however. The story is unfinished and proliferating. My title could also mean “Ishi's own story,” told by Ishi, or on his behalf, a narration giving access to his feelings, his experience, his judgments. But we have only suggestive fragments and enormous gaps: a silence that calls forth more versions, images, endings. “Ishi’s story,” tragic and redemptive, has been told and re-told, by different people with different stakes in the telling. These interpretations in changing times are the materials for my discussion. I. Terror and Healing On August 29th, 1911, a "wild man,” so the story goes, stumbled into civilization. He was cornered by dogs at a slaughterhouse on the outskirts of Oroville, a small town in Northern California. -

California a Tribe of Indians Who Were Still in the Stone Age. the Idea

* THE LAST WILD TRIBE OF CALIFORNIA T. T. Waterman In the fall of 1908 some attention was aroused in the press by a story to the effect that hunters had encountered in the state of California a tribe of Indians who were still in the stone age. The idea of a "wild" tribe in a thickly settled region like California was so novel that it served to awaken a very wide interest. The Indians themselves, however, had meanwhile vanished. Some three years later an individual who had all the appearance of belonging to this group was apprehended in northern California. He was put in jail, and a few days later turned over to the university. Since then he has been received everywhere as the last survivor of his tribe. The whole series of incidents deserves some ex- planation. I think it ought to be said at the outset that the story as given in the papers of that period is quite true. The individual captured in 1911 was a surviving member of a stone-age tribe. He is still alive and well at the university; and he has given from time to time extremely interesting accounts of the history of his people. I should like to explain first of all the rather unusual career of this tribe, and how they happened to remain "wild." The occupation of California by the whites is usually pictured as a peaceful transaction. We hear little of Indian wars in connection with this state. The Cali- fornia tribes pursued, as it happened, a more or less settled mode of life. -

Ishi and Anthropological Indifference in the Last of His Tribe

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 11; June 2013 "I Heard Your Singing": Ishi and Anthropological Indifference in the Last of His Tribe Jay Hansford C. Vest, Ph.D. Enrolled member Monacan Indian Nation Direct descendent Opechanchanough (Pamunkey) Honorary Pikuni (Blackfeet) in Ceremonial Adoption (June 1989) Professor of American Indian Studies University of North Carolina at Pembroke One University Drive (P. O. Box 1510) Pembroke, NC 28372-1510 USA. The moving and poignant story of Ishi, the last Yahi Indian, has manifested itself in the film drama The Last of His Tribe (HBO Pictures/Sundance Institute, 1992). Given the long history of Hollywood's misrepresentation of Native Americans, I propose to examine this cinematic drama attending historical, ideological and cultural axioms acknowledged in the film and concomitant literature. Particular attention is given to dramatic allegorical themes manifesting historical racism, Western societal conquest, and most profoundly anthropological indifference, as well as, the historical accuracy and the ideological differences of worldview -- Western vis-à-vis Yahi -- manifest in the film. In the study of worldviews and concomitant values, there has long existed a lurking "we" - "they" proposition of otherness. Ever since the days of Plato and his Western intellectual predecessors, there has been an attempt to locate and explicate wisdom in the ethnocentric ideological notion of the "civilized" vis-à-vis the "savage." Consequently, Plato's thoughts are accorded the standing of philosophy -- the love of wisdom -- while Black Elk's words are the musings of the "primitive" and consigned to anthropology -- the science of man. Philosophy is, thusly, seen as an endeavor of "civilized" Western man whom in his "science of man" or anthropological investigation may record the "ethnometaphysics" of "primitive" or "developing" cultures. -

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

The Great William Tell, a Girl Who Is Magic at Maths and a TIGER with NO MANNERS!

ORIES! FANTASTIC NEW ST TM Storytime OPERATION UNICORN A mythical being in disguise! BALOO'S BATH DAY Mowgli bathes a big bear! TheTHE Great William GRIFFIN Tell, a Girl Who is Magic at Maths and a TIGER WITH NO MANNERS! ver cle ! ll of ricks ies fu o0l t stor and c characters Check out the fantastic adventures of a smart smith, a girl genius, a wise monk and a clever farmboy! This issue belongs to: SPOT IT! “Don’t worry, you silly bear – I will get you clean!” Storytime™ magazine is published every month by ILLUSTRATORS: Storytime, 90 London Rd, London, SE1 6LN. Luján Fernández Operation Unicorn Baloo’s Bath Day © Storytime Magazine Ltd, 2020. All rights reserved. Giorgia Broseghini No part of this magazine may be used or reproduced Caio Bucaretchi William Tell without prior written permission of the publisher. Flavia Sorrentino The Enchantress of Number Printed by Warners Group. Ekaterina Savic The Griffin Wiliam Luong The Unmannerly Tiger Creative Director: Lulu Skantze L Schlissel The Magic Mouthful Editor: Sven Wilson Nicolas Maia The Blacksmith Commercial Director: Leslie Coathup and the Iron Man Storytime and its paper suppliers have been independently certified in accordance with the rules of the FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council)®. With stories from Portugal, Switzerland, Korea and Uganda! This magazine is magical! Read happily ever after... Tales from Today Famous Fables Operation Unicorn The Unmannerly Tiger When Matilda spots a mythical Can you trust a hungry tiger? being in her garden, she comes A Korean monk finds out when up with a plan to help it get home! 6 he lets one out of a trap! 32 Short Stories, Big Dreams Storyteller’s Corner Baloo’s Bath Day The Magic Mouthful When Baloo has a honey-related Maria learns how to stop accident, Mowgli gives his big arguments – with just a bear friend a bath! 12 mouthful of water! 36 Myths and Legends Around the World Tales William Tell The blacksmith A Swiss bowman shows off and the Iron Man his skill and puts a wicked A king asks a blacksmith governor in his place! 14 to do the impossible.. -

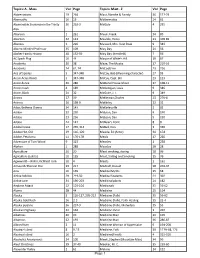

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

The Legend of "Wild Man" Willey

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 19, No. 4 (1997) The Legend of "Wild Man" Willey By Ron Pollack (Reprinted from Pro Football Weekly) As he does for every Eagle home game, Norman Willey is directing the opposing team's players onto the field. As usual, none of these young athletes recognizes Willey. Just as no one recognized the 67-year-old former Eagle the previous game at Veterans Stadium. Just as none of the performers will recognize him at any home games next season. Willey is simply the guy in the NFL Alumni jacket telling them when and where to go as game time draws near. If only they knew the legend of "Wild Man" Willey. Then their eyes would light up. They'd get in line to shake his hand if only they knew. In the 1950's, Wild Man Willey was a pass-rushing terror. In his greatest moment of glory, he turned in a single-game performance that, by all rights, should he immortalized with Babe Ruth's called shot in baseball, Wilt Chamberlain's 1OO-point performance in basketball, and Bob Beamon's record-shattering long jump in the 1968 Olympics. Lightning in a bottle. Unforgettable one-day performances that grow in stature through the passage of time. Willey can bask in no such larger-than-life company for one simple reason. He owns the record that history forgot. The Day was Oct. 26, 1952. The Polo Grounds. Eagle's vs. Giants. The Eagles won 14-1O, but those numbers are relatively unimportant 32 years later. Only one number matters. -

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES in ABC-CLIO’S Handbooks of World Mythology

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES IN ABC-CLIO’s Handbooks of World Mythology Handbook of Arab Mythology, Hasan El-Shamy Handbook of Celtic Mythology, Joseph Falaky Nagy Handbook of Classical Mythology, William Hansen Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Geraldine Pinch Handbook of Hindu Mythology, George Williams Handbook of Inca Mythology, Catherine Allen Handbook of Japanese Mythology, Michael Ashkenazi Handbook of Native American Mythology, Dawn Bastian and Judy Mitchell Handbook of Norse Mythology, John Lindow Handbook of Polynesian Mythology, Robert D. Craig HANDBOOKS OF WORLD MYTHOLOGY Handbook of Chinese Mythology Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright © 2005 by Lihui Yang and Deming An All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yang, Lihui. Handbook of Chinese mythology / Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner. p. cm. — (World mythology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-806-X (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-57607-807-8 (eBook) 1. Mythology, Chinese—Handbooks, Manuals, etc. I. An, Deming. II. Title. III. Series. BL1825.Y355 2005 299.5’1113—dc22 2005013851 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116–1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Noah's Ark Hidden in the Ancient Chinese Characters

Papers Noah’s Ark hidden in the ancient Chinese characters — Voo, Sheeley & Hovee from chapters six to nine.4 The Chinese also have a similar Noah’s Ark story. Notably, a great flood that occurred as a result of the rebellion of a group of people during the legendary period hidden in the (about 2500 BC). In the text of Huai Nan Zi (南子, written in 200 BC),5 legend states that in ancient times, the poles (north, south, east and west) that supported the roof of the ancient Chinese world were broken. As a result, the heavens were broken and the nine states of China experienced continental shift characters and split. Fire broke out and the water from the heavens could not be stopped, causing a flood. Shu Jing (書經, writ- Kui Shin Voo, Rich Sheeley and Larry ten 1000 BC) relates how there was grieving and mourning Hovee all over the earth, and also describes the extent of the flood; how the water reached the sky, and flooded the mountains Legends from ancient China describe a global cata- and drowned all living things. In the midst of this global strophic flood so vast that the waters reached the calamity, a hero by the name of ‘Nüwa’ (女媧) appeared sun and covered the mountains, drowning all the and sealed the flood holes with colourful stones and repaired land-dwelling creatures, including mankind. In the the broken poles using four turtle legs. Nüwa used earth to midst of this global calamity, there stood a legend- create humans to replenish mankind after the flood (Feng ary hero named Nüwa (女媧) who turned back the Su Tong Yi, 風俗通義).6,7 Although the name Nüwa (女 flood and helped to repopulate the world.