Nagai Kafu's Occidentalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East on West in the Arabic Press of the Nahḍa Period1

Studia Islamica 106 (2011) 124-143 brill.com/si “Under Eastern Eyes”: East on West in the Arabic Press of the Nahḍa Period1 Fruma Zachs Haifa University, Israel How many branches of the tree of tamaddun/civilization do we see, that die when their trunk/source is unable to nourish them. There is no real future for Syria or for its civilization unless it is interwoven with the threads of tamaddun and can integrate aspects of European cul- ture, sowing them in the ground, and watering them with the sweat of its toilers.2 (Yaʿqūb Ṣarrūf, 1884) Introduction: From Orientalism to Occidentalism Edward Said’s Orientalism3 (1978) introduced the important historical debate about the crystallization of Western identity/culture versus the Other-the East. One of his main arguments was that ‘in order to know who I am, I must know what I am not’. This concept created an imbalance in which the West predominates in the interaction between the two cultures. 1 * Earlier version of this study was presented at the workshop in the Mediterra- nean Programme: 9th Mediterranean Research Meeting, Florence and Montecatini Term, 2008. The workshop was conducted in the European University Institute- Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Participants in this workshop made signifijicant comments, and I would like to thank them all. I am also grateful to Pro- fessor Ami Ayalon who read earlier versions of this paper. 2 Yaʿqūb Ṣarrūf, “Al-Naẓr fī Ḥāḍirinā wa-Mustaqbalinā,” al-Muqtaṭaf, vol. 8 (1884), p. 196. The fijirst sentence was taken by Ṣarrūf from a poem which I could not trace. -

The Dialectics of Decolonization: Nationalism and Labor Movements in Postwar . Africa"

"The Dialectics of Decolonization: Nationalism and Labor Movements in Postwar . Africa" Fred Cooper CSST Working CRSO .\~orki!lg Paper 884 Paper $480 May 1992 The Dialectics of Decolonization: Nationalism and Labor Movements in Post-War Africa Frederick Cooper University of Michigan January, 1992 Draft Please do not cite or quote without permission of the author The Dialectics of Decolonization: Nationalism and Labor Movements in Post-War Africa Frederick Cooper University of Michigan The triumph of independence movements over colonial rule in Asia and Africa is another one of those metanarratives that needs to be rethought.1 But questioning the metanarrative does not mean that there are an infinite number of narratives of independence jumping around. In the world as it exists today, there are only so many ways to imagine what a state might look like, and that number appears smaller in 1992 than it did in the heady days thirty years go when British and French flags were coming down in one colony after another. Indeed, the narrowing began earlier: as the very question of taking over the state became a realistic possibility, nationalist leaders often began to channel the variety of struggles against colonial authority on which they had drawn--embracing peasants, workers, and intellectuals--into a focus on the apparatus of the state itself and into an ideological framework with a singular focus on the "nation." In the process, many of the possible readings of what an anticolonial movement might be were lost. This paper, focusing on Africa from the end of World War I1 to the early 1960s. -

Occidentalism As a Strategy for Self-Exclusion and Recognition In

Occidentalism as a Strategy for Self-exclusion and Recognition in Mohja Kahf’s The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf Mohja Kahf’ın The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf adlı Eserinde Kendini-dışlama ve Tanınma Stratejisi Olarak Oksidentalizm Ishak Berrebbah Coventry University, UK Abstract Arab American women’s literature has emerged noticeably in the early years of the 21st century. The social and political atmosphere of post 9/11 America encouraged the growth of such literature and brought it to international attention. This diasporic literature is imbued with the discourse of Occidentalism; this not only creates a set of counter-stereotypes and representations to challenge Orientalism and write back to Orientalists, but it also works as a strategy for self-exclusion—by which Arab Americans exclude themselves from wider US society—and paves the way to self- realization. Taking Mohja Kahf’s novel The Girl in the Tangerine Scarf (2006) as a sample of Arab American literature, this paper examines the extent to which Arab American characters including Téta, Wajdy, and Khadra represent and identify white Americans from an Occidentalist point of view to exclude themselves from wider American society, and promote their self-realization and recognition. The arguments and analysis in this paper are outlined within a social identity theoretical framework. Keywords: Diaspora , exclusion , recognition, representation, stereotypes. Öz 21. yüzyılın ilk yıllarında Arap Amerikalı kadın yazını büyük önem kazanmaya başlamıştır. 11 Eylül sonrası Amerika’daki toplumsal ve siyasi atmosfer bu edebiyatın büyümesini beraberinde getirmiş, uluslararası bir önem kazanmasının yolunu açmıştır. Bu diaspora edebiyatı Oksidentalist bir söylemle doludur; bu durum sadece Oryantalizme meydan okuyan ve Oryantalistlere cevap veren bir dizi karşıt- stereotipi ve temsili oluşturmakla kalmaz, aynı zamanda Arap Amerikalıların kendilerini Amerikan toplumunun genelinin dışında tuttukları bir kendini-dışlama stratejisi olarak da işlev görür; böylelikle kendini gerçekleştirmenin de yolu açılmış olur. -

The Imagined West: Exploring Occidentalism

Jukka Jouhki & Henna-Riikka Pennanen THE IMAGINED WEST: EXPLORING OCCIDENTALISM IntrodUction Christianity, the Enlightenment, the industrial revolution and colonialism. Sometimes, on the After the publication of Edward Said’s other hand, ‘a Westerner’ is simply a euphemism Orientalism (1995 [1978]), generalizing for a ‘white’ person, which means that a discourses about the cultures, societies, and Westerner can be anything from a reindeer peoples of the ‘East’ were not taken for granted herder in Northern Lapland to a stockbroker as much as they used to be. In his revered but in Manhattan. Considering the actual socio- also criticized book, Said described exhaustively cultural heterogeneity of the West, it is the traditional distorted European view of the surprising how unproblematically and vaguely East as the polar opposite of the West, or ‘the the term has been used both inside and outside Other’. The Orient was the object of the West’s of academia (see, e.g., Korhonen 2013; Péteri ed. colonization, and of fantasies and generalizations 2010; Makdisi 2002: 772–773; Bozatzis 2014: that had little to do with reality. While there has 130–134). been examination and abundant criticism of The concept of the West has always been Orientalist worldviews for several decades now, dynamic. A major shift in its meaning occurred scholars have only recently begun to examine when Europe lost its colonies in the course of the concept and the shifting meanings of the the 20th century, the United States became the Occident—the ‘West’ (Bavaj 2011: 4). new hegemonic world power, and at the same The Oxford English dictionary tells us time the Americans took a central role in the that ‘the West’ with a capital W—as opposed imagined West. -

Anti-Americanism and the Transatlantic Relationship

| | ⅜ Review Essay Anti-Americanism and the Transatlantic Relationship Jeffrey S. Kopstein The End of the West? Crisis and Change in the Atlantic Order. Edited by Jeffrey Anderson, G. John Ikenberry, and Thomas Risse. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008. 298p. $21.00. Anti-Americanisms in World Politics. Edited by Peter J. Katzenstein and Robert Keohane. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007. 352p. $24.95. Uncouth Nation: Why Europe Dislikes America. By Andrei S. Markovits. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. 302p. $24.95. The big idea in the study of the transatlantic region for the United States and Europe, based not only on Amer- the past five decades has been that of a “security commu- ican power but on the idea that in some important sense nity.” First articulated by Karl Deutsch in the 1950s (Deut- we had become (or at least were becoming) more alike sch et al. 1957), elaborated upon by a subsequent than not, was new. It was widely recognized as a phenom- generation of scholars, and then updated and revised by enon that deserved to be studied. After all, for the previ- Emanuel Adler and Michael Barnett in 1998 and Adler ous century and a half, Europeans and Americans had ⅜ in 2005, a security community can be said to exist when come to the opposite conclusion—that they were essen- a group of people believe that social problems can be tially different—and either celebrated or, less frequently, resolved through “peaceful change.” Above all, war is lamented this fact. The new notion of a security commu- unthinkable. -

DUVALL: Islamist Occidentalism

Duvall, Nadia TITLE INFORMATION TITLE INFORMATION Nadia Duvall ISLAMIST OCCIDENTALISM: SAYYID QUTB AND THE WESTERN OTHER Publication Date: 2019/02 HC c. 240 pages HC ISBN 9783959940627 HC price 75.00 EUR 70.00 GBP All prices are net prices (without VAT) exclusive of postage & handling. Bibliographic record available from http://d-nb.info/1169676944 Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966) was the most important radical Islamist ideologue in modern times. This groundbreaking new study analyses Qutb’s thinking from his early years in Cairo to the radical Islamist stance he adopted towards the end of his life. Occidentalism and Orientalism are mere ‘’duelling essentialisms’’ and shows that Qutb’s views of the Christian European ‘’Other’’ are much more nuanced. Of particularly importance are Qutb’s views on the West in the light of the escalation in violent attacks by militant Islamists targeting Western values. The book covers, amongst others, the following topics: - The discovery & perceptions of the West in the Modern Age - Qutb’s early encounter with modern Western civilisation - The West-East duality, and Qutb’s early views on Islam in relation to Christianity and Judaism - Qutb’s Islamism as a drastic discontinuity of Islamic cumulative tradition „Essentialist views are not the preserve of Orientalists in the Saidian sense. They are the bottom line of all brands of contempt for or hatred of the Other, when the latter is a collective identity, one side’s essentialist rejection prompting the other side’s counter-rejection. There is no better illustration of this than Qutb, the firebrand martyr of Jihadism, whose complex attitude towards the Western Other is closely examined in this fascinating book.“ (Professor Gilbert Achcar, SOAS, University of London) Key Subjects About the Authors/Editors Politics, Islamic Studies, International Nadia Duvall holds a M.A. -

Graduate Center. Spring 2018. Doctoral Program in History

1 City University of New York – Graduate Center. Spring 2018. Doctoral Program in History/Master’s Program in Middle Eastern Studies Room: Course Number: HIST 78110/MES 74500 Tuesday: 6:30 – 8:30 PM. Course Instructor: Simon Davis, [email protected] Office Phone: (718) 289 5677. Palestine Under The British Mandate: Origins, Evolutions and Implications, 1906-1949. This course examines how and with what consequences British interests at the time of the First World War identified and pursued control over Palestine, the subsequent forms such projections took, the crises which followed and their eventual consequences. Particular themes will be explored through analytical discussions of assigned historiographic materials, chiefly recent journal literature. Learning Objectives: Students will be encouraged to evaluate still-contested historical phenomena such as British undertakings with Zionism, colonialist relationships with Arab Palestine, institution-making and economic development, social and cultural transformations, resistance and political violence. This will be understood in the broader context of Middle Eastern politics in the era of late European colonial imperialism. Consonant and particular local experience in Palestine will also be addressed, exploring the effect of British Mandatory administration, especially in ethnic and sectarian-inflected questions of status, social and material conditions, identity, community, law and justice, expression and political rights. Finally, how and why did the Mandate end in a British debacle, Zionist triumph and Arab Palestinian catastrophe, with what main legacies resulting? On the basis of these studies students will each complete a research essay from the list below, along with a number of smaller critical exercises, and a final examination. -

Turkish Occidentalism and Representations of Western Women in Turkish Media

Turkish Occidentalism and Representations of Western Women in Turkish Media Per Bauhn Fatma Fulya Tepe professor of practical philosophy linnaeus university [email protected] assistant professor istanbul aydın university [email protected] Abstract “Occidentalism” is an umbrella term for various stereotyped images of the West. It is typically gendered, implying views of Western moral standards that are often filtered through a certain perception of Western women. We will look at the particular case of Turkish media representations of Western women from the point of view of occidentalism. Western women are described in positive terms when they choose to marry Turkish men, convert to Islam, and move to Turkey. On the other hand, when these women are described in their Western context, they are often portrayed as morally and sexually confused. We hypothesize that these descriptions of Western women exemplify a Turkish occidentalism, morally othering the West and Western women. While our material may not suffice to say anything about the representativity of these views, it is at least sufficient to confirm and illustrate a hypothesis that such an occidentalism indeed exists in Turkish media. keywords: occidentalism, Turkey, Western women, Turkish media, othering To cite this article: Bauhn, P. and Tepe, F. F. (2017). Turkish Occidentalism and Representations of Western Women in Turkish Media. İleti-ş-im, Galatasaray University Journal of Communication, 26, 65-82. DOI: 10.16878/gsuilet.324193. 66 İleti-ş-im 26 • haziran/june/juin 2017 Résumé Occidentalisme turc et représentations des femmes occidentales dans les médias turcs “L’occidentalisme” est un terme générique pour diverses images stéréotypées de l’Occident. -

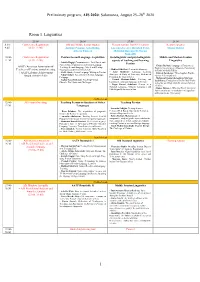

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

A (Short) History of the Clash of Civilizations

Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Volume 21, Number 2, June 2008 A (short) history of the clash of civilizations Arshin Adib-Moghaddam School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Abstract Where does the clash of civilizations thesis and its underlying us-versus- them mentality come from? How has the idea been engineered historically and ideologically in the ‘east’ and ‘west’? What were the functions of Christianity and Islam to these ends? These are some of the questions that will be discussed in this article that engages both the clash of civilizations thesis and the discourse of ‘Orientalism’ more generally. Dissecting the many manifestations of mutual retributions, the article establishes the nuances of the ‘clash’ mentality within the constructs we commonly refer to as ‘Islam’ and the ‘west’, showing how it is based on a questionable ontology, how it has served particular political interests and how it is not inevitable. What is presented, rather, is a short genealogy of this idea, dispelling some of its underlying myths and inventions along the way. Introduction One must not suppose that grand theories such as the ‘clash of civilizations’ are a recent invention nor that the epistemology of such can be divorced from its historical context. Ironically, today’s proponents of the so-called ‘clash’ thesis suggest they can escape the fact that their reference to a seemingly coherent past implicates them in the genealogy of the idea. In other words, by attempting to persuade us that the supposed conflict between Islam and the west has always existed, the very agents of the idea orchestrate an historical conspiracy as such. -

I Диалог Философий * Dialogue of Philosophies

I ДИАЛОГ ФИЛОСОФИЙ * DIALOGUE OF PHILOSOPHIES Hassan Hanafi (Cairo University, Egypt) FROM ORIENTALISM TO OCCIDENTALISM Orientalism as a field of research emerged in the West in modern times, since the Renaissance. It appeared during the second cycle of the history of the West, af- ter the classical period and the Patristics, the medieval time and the Scholastics. It reached its peak in the 19th century, and paralleled the development of other Western schools of thought such as rationalism, historicism, and structuralism. Orientalism has been the victim of historicism from its formation, via meticu- lous and microscopic analysis, indifferent to meaning and significance. Orientalism expresses the searching subject more than it describes the object of research. It re- veals Western mentality more than it intuits Oriental Soul. It is motivated by the anguish of gathering the maximum of useful information about countries, peoples and cultures of the Orient. The West, in its expansion outside its geographic bor- ders, tried to understand better in order to dominate better. Knowledge is power. Classical Orientalism belongs for the most part to similar aspects of colonial cul- ture in the West such as Imperialism, Racism, Nazism, Fascism, a package of he- gemonic Ideologies and European Supremacy. It is a Western activity, an expres- sion of Western Elan Vital, determining the power relationship between the Self and the Other; between the West and the Non West; between Europe from one side and Asia, Africa and Latin America, from the other side; between the New Word and the classical world; between modern times and ancient times. This brutal judgement, without nuances, is undoubtedly a severe and painful one, but a real one on the level of historical unconsciousness of peoples, on the level of images even if it is inaccurate enough on the level of concepts. -

Does Anti-Americanism Exist? Experimental Evidence from France

Does Anti-Americanism Exist? Experimental Evidence from France Richard K. Herrmann∗ and Joshua D. Kertzery Last revised: May 30, 2015 Abstract: There are many debates in Washington about anti-Americanism: where it comes from, what implications it has for US foreign policy, and whether it can be eradicated by careful public diplomacy. Yet before we search for a cure for the disease or ascertain how severe its symptoms are, we need to be able to diagnose it in the first place. One reason why anti-Americanism attracts so much attention is that it is often understood as a form of prejudice rather than mere disagreement with American policies. If this is the case, however, we need to be able to differentiate unpopularity from the prejudice believed to be causing it. To do so, we present three novel experiments embedded in a national survey in France in 2009-10, studying anti-Americanism like how political scientists study other forms of prejudice. Our findings counter conventional wisdom in two ways. First, we find relatively little evidence of anti-Americanism in France. Second, a key predictor of anti-Americanism in France is nationalism, but not in the direction some IR scholars might expect: the more attached the French are to their country, the more of a break they give the United States compared to other great powers who behave similarly. The results thus suggest that nationalism and the fostering of a common ingroup are not contradictory forces. ∗Professor, Department of Political Science, The Ohio State University. 2140 Derby Hall, 154 N. Oval Mall, Columbus OH 43210.