Trading Firms in Colonial India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rallis India: the Turnaround Story

Volume I Issue 2 July-September 09 CASE STUDY RALLIS INDIA: THE TURNAROUND STORY Contents Introduction Section 1: The backdrop Rallis: Empire and after The global pesticide industry The Indian pesticide industry Section 2: The Rallis India story Turbulent times Rallis goes downhill Restructuring of Rallis Record losses Section 3: The turnaround story The first steps The turnaround plan The impact Maintaining the momentum Indore Management Journal gratefully acknowledges the permission to reprint this article, by Tata Management Training Centre (TMTC). Extensive interviews and research were undertaken by B. Bowonder and Shambhu Kumar. IMJ (IIM, INDORE) 53 B. Bowonder and Shambhu Kumar Volume I Issue 2 July-September 09 Introduction Rallis India is one of India's leading agrochemical companies, with a comprehensive portfolio of crop protection chemicals, seed varieties and specialty plant nutrients. It has an extensive nationwide distribution system supported by an efficient marketing and sales team. The company has marketing alliances with several multinational agro-chemical companies, including FMC, Nihon Nohyaku, DuPont, Syngenta, Makhteshim Agan and Bayer CropScience. Rallis India's business has been through steep highs and lows in the last 10-15 years. The company's fortunes have yo-yoed up and down, its range of business areas have widened and narrowed dramatically, and it has experienced significant changes in its economic environment. Internally, it has faced diverse issues and problems such as spiralling wages, under-productivity, competition from imports and multinational companies (MNCs), from the '80s onwards. In the post-liberalisation economy, Rallis's businesses underwent strong pushes and pulls, culminating in a phase of heavy losses in 2000-03. -

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Risk, Information and Capital Flows: the Industrial Divide Between

Discrimination or Social Networks? Industrial Investment in Colonial India Bishnupriya Gupta No 1019 WARWICK ECONOMIC RESEARCH PAPERS DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Discrimination or Social Networks? Industrial Investment in Colonial India Bishnupriya Gupta1 May 2013 Abstract Industrial investment in Colonial India was segregated by the export oriented industries, such as tea and jute that relied on British firms and the import substituting cotton textile industry that was dominated by Indian firms. The literature emphasizes discrimination against Indian capital. Instead informational factors played an important role. British entrepreneurs knew the export markets and the Indian entrepreneurs were familiar with the local markets. The divergent flows of entrepreneurship can be explained by the comparative advantage enjoyed by social groups in information and the role of social networks in determining entry and creating separate spheres of industrial investment. 1 My debt is to V. Bhaskar for many discussions to formalize the arguments in the paper. I thank, Wiji Arulampalam, Sacsha Becker Nick Crafts and the anonymous referees for helpful suggestions and the participants at All UC Economic History Meeting at Caltech, ESTER Research Design Course at Evora and Economic History Workshop at Warwick for comments. I am grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council, UK, for support under research grant R000239492. The errors are mine alone. 1 Introduction Bombay and Calcutta, two metropolitan port cities, experienced very different patterns of industrial investment in colonial India. One was the hub of Indian mercantile activity and the other the seat of British business. The industries that relied on the export market attracted investment from British business groups in the city of Calcutta. -

Working Paper No. 223 the MID-THIRTIES" TIRTHANKAR ROY

Working Paper No. 223 RELATIONS CX PRODUCTION IN HANDLOOM WEAVING IN THE MID-THIRTIES" TIRTHANKAR ROY - * The Paper forms part of a larqcr study under preparation, I have benefjtted from d' scussions with San:ay Kumar whose on- golag projeat on powerlooms his been a source of inspiration. I wish to thank Sumi-t Guha, Mihir Shah, Raman Mahadevan and Mridul Eapen for their.comments on a draft. I Centre ifor Development Studies, Ulloor, 'irivandrum - 11 . Descriptions of the hendloom industry in the thirties contain the suggestion that competition with machine-made cloth induced adaptations rather than 'a passive decay in the textile handicrafts. The nalrn conp~nentsof this process were diversifi- cation into 'ligher valued prc lucts, from cdtton to noncottan for instance, accompanied by differentiations in the technoeconomf c structure ta which the rapid yrohth of handloom factories and small scale powerlooms bears witness. The paper attempts a survey of the second of these components, relations1 changes. The process in its most general form involved reduction of ' independent' weavers to ' dependencef , that is, a progressive erosion of. the right of posseosion over final product. Two basic f orms of dependence can be dis:inguished: contract for sale of products tied to a particular merchant and contract for sale of labour. At the other end emergec large producers usually with interests in cloth trade. Pure ommercial capital was thus becoming differentiated and weaker as a class. Regional differences .in the strength and direction of the basic movement were considerable. The industry in the south, .including Bombay-Decczn and Hyderabid, proved more progressive with greater stratification among prcducers while in the east. -

In Late Colonial India: 1942-1944

Rohit De ([email protected]) LEGS Seminar, March 2009 Draft. Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without permission. EMASCULATING THE EXECUTIVE: THE FEDERAL COURT AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN LATE COLONIAL INDIA: 1942-1944 Rohit De1 On the 7th of September, 1944 the Chief Secretary of Bengal wrote an agitated letter to Leo Amery, the Secretary of State for India, complaining that recent decisions of the Federal Court were bringing the governance of the province to a standstill. “In war condition, such emasculation of the executive is intolerable”, he thundered2. It is the nature and the reasons for this “emasculation” that the paper hopes to uncover. This paper focuses on a series of confrontations between the colonial state and the colonial judiciary during the years 1942 to 1944 when the newly established Federal Court struck down a number of emergency wartime legislations. The courts decisions were unexpected and took both the colonial officials and the Indian public by surprise, particularly because the courts in Britain had upheld the legality of identical legislation during the same period. I hope use this episode to revisit the discussion on the rule of law in colonial India as well as literature on judicial behavior. Despite the prominence of this confrontation in the public consciousness of the 1940’s, its role has been downplayed in both historical and legal accounts. As I hope to show this is a result of a disciplinary divide in the historical engagement with law and legal institutions. Legal scholarship has defined the field of legal history as largely an account of constitutional and administrative developments paralleling political developments3. -

Jute -The Golden Fibre of Bangladesh a Framework to Resolve

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) Vol 4, No.14, 2012 Jute -The Golden Fibre of Bangladesh A Framework to Resolve the Current Critical Situations Sadia Afroj School of Business and Management, Khulna University, Khulna, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In Bangladesh n ine million farmers, laborers, workers and 45 million dependents, earn less than a dollar a day per family to grow jute in rotation with rice . They grow almost three million tons on 1.6 million hectares of land. Jute provides a necessary break between rice crops and four times its weight in bio -mass to enrich the soil. It also provides a vital cash flow for people who live at the very margins of subsistence. It has been important to jute based farming syst ems in parts of Bangladesh for over a century and this fundamental has not changed. Key word: Jute, current problems, framework, resolve 1. Introduction of Jute The jute plant grows six to ten feet in height and stem of the jute plant is covered with th ick bark and it contains the fibre . In two or three months, the plants grow up and then they are cut, tied up in bundles and kept under water for fermentation for several days. Thus the stems rot and the fibres from the bark, become loose. Then the cultiva tors pull of the fibre s from the bark and wash the fibre s very carefully, dry them in the sun and put them in bundles for sale. -

Myth, Language, Empire: the East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-10-2011 12:00 AM Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 Nida Sajid University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Nida Sajid 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Sajid, Nida, "Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 153. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/153 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 (Spine Title: Myth, Language, Empire) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Nida Sajid Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nida Sajid 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ____________________________ Dr. -

Letter from Bombay

40 THE NATIONAL MEDICAL JOURNAL OF INDIA VOL. 8, NO.1, 1995 Letter from Bombay THE ONE HUNDRED AND FIFfIETH ANNIVERSARY Sohan Lal Bhatia (the first Indian to be appointed Prinicipal OF THE GRANT MEDICAL COLLEGE AND SIR J. J. of the Grant Medical College), Jivraj Mehta (Mahatma GROUP OF HOSPITALS Gandhi's personal physician) and Raghavendra Row (who When Sir Robert Grant took over the reins as Governor suggested that leprosy be treated with a vaccine prepared of Bombay in 1834, he was struck by the poor state of from the tubercle bacillus). There were also V. N. Shirodkar public health throughout the Presidency. At his instance, (best known for his innovative operations in obstetrics and Dr Charles Morehead and the Bombay Medical and Physical gynaecology) and Rustom N. Cooper (who did pioneering Society conducted a survey throughout the districts of the work on blood transfusion as well as on surgery for diseases then Bombay Presidency on the state of health, facilities for of the nervous system). medical care and education of practising native doctors. On More recently, two Noshirs-Drs Noshir Antia (who has the basis of this exemplary survey, it was decided to set up done so much to rehabilitate patients with leprosy) and a medical college for Indian citizens with the intention of Noshir Wadia (the neurologist) have brought more fame to sending them out as full-fledged doctors. these institutions. The proposal encountered stiff opposition. A medical Factors favouring excellence at these institutions school had floundered and collapsed within recent memory. Among the arguments put forth was the claim that natives All of us, however, who love the Grant Medical College did not possess the faculties and application necessary for and the J. -

Exploring the Future Potential of Jute in Bangladesh

agriculture Article Exploring the Future Potential of Jute in Bangladesh Sanzidur Rahman 1,* ID , Mohammad Mizanul Haque Kazal 2,† ID , Ismat Ara Begum 3,† and Mohammad Jahangir Alam 4,† ID 1 School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK 2 Department of Development and Poverty Studies, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh; [email protected] 3 Department of Agricultural Economics, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh; [email protected] 4 Department of Agribusiness and Marketing, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh 2202, Bangladesh; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1752-585911; Fax: +44-1752-584710 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 17 September 2017; Accepted: 24 November 2017; Published: 25 November 2017 Abstract: The study assesses the future potential of the jute sector in Bangladesh by examining its growth performance, international competitiveness, profitability, and production efficiency using national time-series data of over the period 1973–2013 and farm survey data from 289 farmers from two major jute growing areas of Bangladesh. Results revealed that the jute sector has experienced substantial growth in area, production, productivity, prices, and exports. However, productivity has stagnated during the latter 10-year period (2004–2013), while it grew at a rate of 1.3% per annum (p.a.) during the first 31-year period (1973–2003). Only traditional jute production is globally competitive, although financial profitability of white jute is relatively higher (benefit cost ratio = 1.24 and 1.17, respectively). Land, labor, and irrigation are the main productivity drivers for jute. -

The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I*

The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I* Paul R. Brass** During the past three decades, the dominant party in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (U. P.), the Indian National Congress, has undergone a secular decline in its support in state legislative assembly elections. The principal factor in its decline has been its inability to establish a stable basis of support among the midle peasantry, particularly among the so-called 'backward castes', with landholdings ranging from 2.5 to 30 acres. Disaffected from the Congress since the 1950s, these middle proprietary castes, who together form the leading social force in the state, turned in large numbers to the BKD, the agrarian party of Chaudhuri Charan Singh, in its first appearance in U. P. elections in 1969. They also provided the central core of support for the Janata party in its landslide victory in the 1977 state assembly elections. The politicization of the middle peasantry in this vast north Indian province is no transient phenomenon, but rather constitutes a persistent factor with which all political parties and all governments in U. P. must contend. I Introduction This articlet focuses on the state of Uttar Pradesh (U. P.), the largest state in India, with a population of over 90 million, a land area of 113,000 square miles, and a considerable diversity in political patterns, social structure, and agricul- tural ecology. My purpose in writing this article is to demonstrate how a program of modest land reform, designed to establish a system of peasant proprietorship and reenforced by the introduction of the technology of the 'green revolution', has, in the context of a political system based on party-electoral competition, enhanced the power of the middle and rich peasants. -

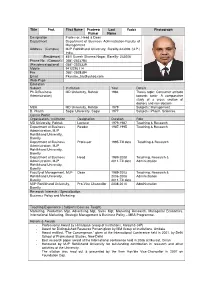

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Kumar Last Name Yadav Photograph

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Last Yadav Photograph Kumar Name Designation Professor, Head & Dean Department Department of Business Administration-Faculty of Management Address (Campus) MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly-243006 (U.P.) India. (Residence) 45/II Suresh Sharma Nagar, Bareilly- 243006 Phone No (Campus) 0581 -2523784 (Residence)optional 0581-2525339 Mobile 9412293114 Fax 0581 -2528384 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D(Business MD University, Rohtak 1984 Thesis topic: Consumer attitude Administration) towards tonic- A comparative study of a cross section of doctors and non-doctors MBA MD University, Rohtak 1979 Subjects: Management B. Pharm Sagar University, Sagar 1977 Subjects: Pharm. Sciences Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role MD University, Rohtak Lecturer 1979-1987 Teaching & Research Department of Business Reader 1987-1995 Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Professor 1995-Till date Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Head 1989-2008 Teaching, Research & Administration, MJP 2011-Till date Administration Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Faculty of Management, MJP Dean 1989-2003 Teaching, Research & Rohilkhand University, 2006-2008 Administration Bareilly 2011-Till date MJP Rohilkhand University, Pro-Vice Chancellor 2008-2010 Administration Bareilly Research Interests / Specialization Business Policy and Marketing Teaching -

Summary and Conclusion

C H A P T E R - 8 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION Jute is a principal cash crop of North Bengal, the name commonly· attributed to the region which includes five districts of West Bengal, viz, Maida, West Dinaj pur, Gooch- Behar, Jalpa igur i and Dar j eel ing. With effect from 01.04.92 the district of West Dinajpur has been -reconstituted into two districts, i.e. North Dinajpur and South Dinajpur. There are two species of jute, viz. cor chorus capsularies and cor chorus olitorius. The commercial names are white jute and Tossa jute respectively. Jute, the golden fibre plays a very imp.'Jttant role in the economy of India, especially in the rural economy of jute grm1ing states. Jute· manufactures account for. nea-rly 7io of our total foreign exchange earnings. Over 2 lakhs of industrial workers are employed directly in the jute industry. ~nd about 20 lakh people earn their livelihood from secondary sectors of the industry. About 40 lakh farmer families of various states are engaged in the production of jute fibre. The demand for raw jute is derived demand, i.e, raw jute is demanded only for production of jute goods. In India jute mills came to be established in the 1850's. The first jute-spinning mill was established at Rishra in 1955 by George Acland. By 1873 only 5 jute mills . had come into existence with a meagre 1250 looms. In the jute trade European businessmen were involved at alinost every stage from the buyi~g of jute from the peasant up to the shipping of .