California State University, Northridge a Study And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 94 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #307 - ORIGINAL ART BY MAUD HUMPHREY FOR GALLANT LITTLE PATRIOTS #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus (The Doll House) #357 - Meggendorfer Das Puppenhaus #195 - Detmold Arabian Nights #526 - Dr. Seuss original art #326 - Dorothy Lathrop drawing - Kou Hsiung (Pekingese) #265 - The Magic Cube - 19th century (ca. 1840) educational game Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOGUE WILL NOT BE ON RARE TUCK RAG “BLACK” ABC 5. ABC. (BLACK) MY HONEY OUR WEB SITE FOR A FEW WEEKS. -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Thursday, 05/20/10, 09:41 AM Holden Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.1 3.0 English Fiction 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Jon Buller LG 2.6 0.5 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 4.8 2.0 English Fiction 6201 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen LG 3.1 2.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 166 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson MG 5.2 5.0 English Fiction 9001 The 500 Hats of Bartholomew CubbinsDr. Seuss LG 3.9 1.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 11151 Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner LG 2.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 61248 Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved BooksKay Winters LG 3.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 101 Abel's Island William Steig MG 6.2 3.0 English Fiction 13701 Abigail Adams: Girl of Colonial Days Jean Brown Wagoner MG 4.2 3.0 English Nonfiction 9751 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger LG 2.8 0.5 English Fiction 907 Abraham Lincoln Ingri & Edgar d'Aulaire 4.0 1.0 English 31812 Abraham Lincoln (Pebble Books) Lola M. Schaefer LG 1.5 0.5 English Nonfiction 102785 Abraham Lincoln: Sixteenth President Mike Venezia LG 5.9 0.5 English Nonfiction 6001 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith LG 5.0 3.0 English Fiction 102 Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt MG 8.9 11.0 English Fiction 7201 Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg LG 1.2 0.5 English Fiction 17602 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie:Kristiana The Oregon Gregory Trail Diary.. -

Mbh-Study-Guide.Pdf

Table of Contents Teacher Information: What Happens in Madeline and the Bad Hat .......Page 2 Creating a Musical Theatre Production ..................................Page 3 Meet the Characters....................Page 4 Learning About Madeline Through Lines and Lyrics .........Page 5 Learning About Pepito Through Lines and Lyrics .........Page 6 About the Dialogue.....................Page 7 Write to ArtsPower!....................Page 8 ArtsPower National Touring Theatre Gary W. Blackman Mark A. Blackman Executive Producers Madeline and the Bad Hat Based on the book by Ludwig Bemelmans Based on the book MADELINE AND THE BAD HAT by Ludwig Bemelmans. Copyright 1956 by Ludwig Bemelmans. Copyright© renewed by Madeleine Bemelmans and Barbara Bemelmans Marciano, 1984. All rights reserved. Published by The Viking Press, a division of Penguin Books USA, Inc. New York, NY. Presented under an exclusive agreement. Book and Lyrics by Greg Gunning Music by Richard DeRosa Costume Design & Construction by Fred Sorrentino Set Construction by Please photocopy any or all of the following pages Tom Carroll Scenic, Jersey City, NJ to distribute to students. Madeline and the Bad Hat Performance Study Buddy © 2007 Written by Micaela Robb-McGrath Edited by Rosalind M. Flynn Designed by Bette Friedlander/ Cowles Graphic Design Study Buddy What Happens in Teacher Information Madeline and the Bad Hat? This study guide is designed to help you and To help students understand the action of your students prepare the play, read this plot summary to them. for, enjoy, and discuss ArtsPower’s one-act The main characters’ names appear in musical play, Madeline boldface type. and the Bad Hat. This guide contains Because Madeline and the Bad Hat is a background information musical — a story in which actors speak and cross-curricular and sing to tell the story — the words and activities to complete songs tell the audience about the plot, both before and after the performance. -

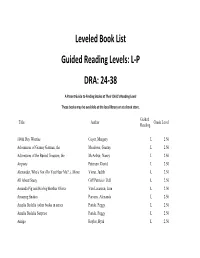

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L-P DRA: 24-38

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L‐P DRA: 24‐38 A Parent Guide to Finding Books at Their Child’s Reading Level These books may be available at the local library or at a book store. Guided Title Author Grade Level Reading 100th Day Worries Cuyer, Margery L 2.50 Adventures of Granny Gatman, the Meadows, Granny L 2.50 Adventures of the Buried Treasure, the McArthur, Nancy L 2.50 Airports Petersen, David L 2.50 Alexander, Who's Not (Do You Hear Me?..)..Move Viorst, Judith L 2.50 All About Stacy Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Amanda Pig and Her big Brother Oliver Van Leeuwen, Jean L 2.50 Amazing Snakes Parsons, Alexanda L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia (other books in series Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia Surprise Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amigo Baylor, Byrd L 2.50 Anansi the Spider McDermott, Gerald L 2.50 Animal Tracks Dorros, Arthur L 2.50 Annabel the Actress Starring in Gorilla My Dream Conford, Ellen L 2.50 Anna's Garden Songs Steele, Mary Q. L 2.50 Annie and the Old One Miles, Miska L 2.50 Annie Bananie Mover to Barry Avenue Komaiko, Leah L 2.50 Arthur Meets the President Brown, Marc L 2.50 Artic Son George, Jean Craighead L 2.50 Bad Luck Penny, the O'Connor Jane L 2.50 Bad, Bad Bunnies Delton, Judy L 2.50 Beans on the Roof Byare, Betsy L 2.50 Bear's Dream Slingsby, Janet L 2.50 Ben's Trumpet Isadora, Rachel L 2.50 B-E-S-T Friends Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Best Loved doll, the Caudill, Rebecca L 2.50 Best Older Sister, the Choi, Sook Nyul L 2.50 Best Worst Day, the Graves, Bonnie L 2.50 Big Al Yoshi, Andrew L 2.50 Big Box of Memories Delton, -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

Razzle Dazzle Reading Circus: a Bibliography of Books in Recorded and Braille Formats for Young Readers from Preschool Through Junior High

--.DOCUMENT RESUME ED 373 790 IR 055 150 AUTHOR Sumner, Mary Ann, Comp. TITLE Razzle Dazzle Reading Circus: A Bibliography of Books in Recorded and Braille Formats for Young Readers from Preschool through Junior High. Silver Summer Scrapbook--Summer Library Program, 1993. INSTITUTION Florida State Dept. of Education, Tallahassee. Div. of Blind Services. PUB DATE 15 Mar 93 NOTE 2 7ompiled in conjunction with the 1993 Florida Summer Library Program (see ED 360 990). For related bibliographies, see IR 055 149-155. AVAILABLE FROMFlorida Department of Education, Division of Blind i Services, Bureau of Braille and Talking Book Library Services, 420 Platt St., Daytona Beach, FL 32114-2804 (free; availab.e in large print, cassette, and braille formats). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Braille; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Fiction; Media Adaptation; Preschool Education; Reading Materials; State Libraries; Summer Programs; *Talking Books; Visual Impairments IDENTIFIERS *Circuses; Florida ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography comprises an alphabetical listing of 34 books on circuses available in special formats. The list has books about true circus stories; make believe stories; and circus animals. The reading levels of the books range from preschool through junior high school. Formats included in the bibliography are cassette books; braille books; and recorded discs. Each entry contains author (if available); title; annotation; and grade level. Also included are a title index and an order form. (JLB) ********::******AA.*I.********;;****i,---********************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** Razz eleazzlie L°J Reading CircuS U.S. -

Madeline and the Bad

2015-2016 Resource Guide NOVEMBER 19, 2015 9:30 & 11:30 A.M. • VICTORIA THEATRE The Frank M. FOUNDATION www.victoriatheatre.com Curriculum Connections You will find these icons listed in the resource guide next to the activities that elcome to the 2015-2016 indicate curricular connections. Teachers and parents are encouraged to adapt all Frank M. Tait Foundation of the activities included in an appropriate way for your students’ age and abilities. W MADELINE AND THE BAD HAT fulfills the following Ohio Standards and Benchmarks Discovery Series at Victoria Theatre for grades Kindergarten through Grade 4: Association. We are very excited to be your partner in providing professional English/Language Arts Standards Grade 2- 1CE-7CE, 1PR-3PR, 1RE-6RE Kindergarten- CCSS.ELA-Literacy. Grade 3- 1CE-5CE, 1PR-6PR, 1RE-5RE arts experiences to you and your RL.K.3, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.K.9 Grade 4- 1CE-6CE, 1PR-7PR, 1RE-5RE students! Grade 1- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.1.2, Madeline and her adventures have been CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.1.3, CCSS.ELA- National Core Arts Theatre a part of children’s literature since her Literacy.RL.1.6, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.1.9 Standards Grades Kindergarten- 4 first story was published in 1939. In Grade 2- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.1, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.2.2, CCSS.ELA- CREATING, PERFORMING, RESPONDING, addition to the whimsical illustrations, CONNECTING Anchor Strands 1-11 readers from around the world have Literacy.RL.2.3, CCSS.ELA-Literacy. RL2.4, CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL2.5, CCSS. -

Madeline in New York: the Art of Ludwig Bemelmans

Madeline in New York: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans July 4, 2014 - October 13, 2014 Selected PR Images Madeline at the Paris Flower Market , 1955 Oil on canvas The Estate of Ludwig Bemelmans “The little girls all cried ‘Boo-hoo!’” 1956/57 TM and © Ludwig Bemelmans, LLC Madeline and the Bad Hat (The Viking Press, 1956/57) Gouache Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce TM and © Ludwig Bemelmans, LLC “Even Miss Clavel said,” 1956/57 “One nice morning Miss Clavel said,” 1939 Madeline and the Bad Hat (The Viking Press, 1956/57) Madeline (Simon & Schuster, 1939) Gouache Crayon and watercolor Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce TM and © Ludwig Bemelmans, LLC TM and © Ludwig Bemelmans, LLC This exhibition is organized by The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, Amherst, MA Note: Editorial use only. Works must be used in their entirety with no cropping, detailing, overprinting, or running across the gutter. Additionally, the reproductions must be fully captioned as provided. “And low,” 1953 “They went looking high,” 1953 Panel from Aristotle Onassis' yacht The Christina Panel from Aristotle Onassis' yacht The Christina Oil on canvas Oil on canvas Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce TM and © Ludwig Bemelmans, LLC TM and © Ludwig Bemelmans, LLC Cover for Madeline’s Rescue , 1953 Madeline and the Bad Hat (The Viking Press, 1956/57) Madeline’s Rescue (The Viking Press, 1953) Dummy Cover for Madeline and the Bad Hat , ca. Gouache 1956/57 Iris & B. -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

Download Madeline and the Gypsies Free Ebook

MADELINE AND THE GYPSIES DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Ludwig Bemelmans | 64 pages | 07 Aug 2001 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780140566475 | English | New York, NY, United States Madeline and the Gypsies Everything is going smoothly until it starts raining and all hell breaks loose. I remember the main characters' cute harlequin costumes. Whenever Madeline and the Gypsies see this book I need to read! This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Lists with This Book. Madeline and the Gypsies like so many of the books from my childhood and there were probably hundredsI don't remember the story all that well. Unfortunately a storm cause the big wheel to be stopped, when the others are evacuated Madeline and Pepito are stranded in a car at the top. After spending the next day travelling to a new destination and learning some acrobatics they decide that life in the circus is more fun than school and stay on to perform there. Madeline stories are so bizarre, and politically incorrect at times, but the illustrations are breathtaking. The leader; Mama Gypsy recruits the Strongman, the Clown's and even the troupe's elephant's to rescue Madeline from the ferris wheel. Enlarge cover. The kids have a lot of fun and enjoy not having to brush their teeth or have a bedtime. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. My only discomfort stemmed from the depiction of the Roma, or gypsy people. Want to Read saving…. She has become quite Madeline and the Gypsies to them and does not want them to leave. The next morning the "Lion" strolls through the county and wandered too far next to farm-land; frightening the Carrel- farm animals and angering the farmers. -

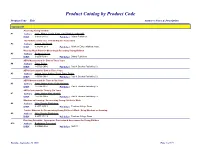

Product Catalog by Product Code

Product Catalog by Product Code Product Code Title Author's Notes & Description Assessment Assessing Young Children A1 Authors Gayle Mindes, Harold Ireton, Carol Mardell-Czudnowski ISBN 0-8273-6211-0 Publisher Delmar Publishers The Portfolio and its use: A Road Map for Assessment A2 Authors Sharon MacDonald ISBN 0-942388-20-8 Publisher Southern Early Childhood Assoc. Week by Week Plans for Observing & Recording Young Children A3 Authors Barbara A. Nilsen ISBN 0-8273-7646-4 Publisher Delmar Publishers AEPS Measurement for Birth to Three Years A4 Authors Diane Bricker ISBN 1-55766-095-6 Publisher Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. AEPS Curriculum for Birth to Three Years A5 Authors Juliann Cripe, Kristine Slentz, Diane Bricker ISBN 1-55766-096-4 Publisher Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. AEPS Measurement for Three to Six Years A6 Authors Diane Bricker, Kristie Pretti-Frontczak ISBN 1-55766-187-1 Publisher Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. AEPS Curriculum for Three to Six Years A7 Authors Diane Bricker, Misti Waddell ISBN 1-55766-188-x Publisher Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. Windows on Learning: Documenting Young Children’s Work A8 Authors Helm, Beneke, Steinheimer ISBN 0-8077-3678-3 Publisher Teachers College Press Teacher Materials for Documenting Young Children’s Work: Using Windows on Learning A9 Authors Helm, Beneke, Steinheimer ISBN 0-8077-3711-9 Publisher Teachers College Press Reaching Potentials: Appropriate Curriculum & Assessment for Young Children A10 Authors Bredekamp, Rosengrant ISBN 0-935989-53-6 Publisher NAEYC Tuesday, September 29, 2009 Page 1 of 173 Product Code Title Author's Notes & Description Reaching Potentials: Transforming Early Childhood Curriculum & Assessment A11 Authors Bredekamp, Rosegrant ISBN 0-935989-73-0 Publisher NAEYC Developmental Screening in Early Childhood: A Guide A12 Authors Samuel J.