Illuminating the Thought of the Victors Foreword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Currents 31 | 1 Introduction

UC Berkeley Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review Title Introduction to "Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations" Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5kj9c57m Journal Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review, 1(31) ISSN 2158-9674 Author Tsultemin, Uranchimeg Publication Date 2019-06-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction to “Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations” Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Introduction to ‘Buddhist Art of Mongolia: Cross-Cultural Connections, Discoveries, and Interpretations.’” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 1– 6. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/introduction. A comparative and analytical discussion of Mongolian Buddhist art is a long overdue project. In the 1970s and 1980s, Nyam-Osoryn Tsultem’s lavishly illustrated publications broke ground for the study of Mongolian Buddhist art.1 His five-volume work was organized by genre (painting, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts) and included a monograph on a single artist, Zanabazar (Tsultem 1982a, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989). Tsultem’s books introduced readers to the major Buddhist art centers and sites, artists and their works, techniques, media, and styles. He developed and wrote extensively about his concepts of “schools”—including the school of Zanabazar and the school of Ikh Khüree—inspired by Mongolian ger- (yurt-) based education, the artists’ teacher- disciple or preceptor-apprentice relationships, and monastic workshops for rituals and production of art. The very concept of “schools” and its underpinning methodology itself derives from the Medieval European practice of workshops and, for example, the model of scuola (school) evidenced in Italy. -

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism By C. Fred Smith Founders: Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha. The Tibetan form grew out of the teachings Kamalashila who defended traditional Indian Buddhism in Tibet against the Chinese form. Date: Founded between 600 and 400 BC in Northern India; Buddhism influenced Tibetan religion as early as AD 200, but only began to take on its Tibetan character after 792 AD. Its full expression as a Lamaist religion (one dependent on lamas or gurus to guide meditation) began in the 1200s, with the institution of the Dalai Lama in the 1600s. Key Words: Lama, Bon, Reincarnation, Dharma and Sangha BACKGROUND Tibetan Buddhism focuses on disciplined meditation to achieve enlightenment, which is the realization that life is impermanent, and the accompanying state of bliss. Its unusual character, different from other forms of Buddhism, lies in two facts. First, it traces its practices back to the earliest form of Buddhism from Northern India. Certain practices are similar to those of Hindu practitioners,1 and the meditative discipline is similar to that practiced in the first Buddhist Sanghas, or monastic communities. Second, its practices and “peculiar, even eerie character” are a result of its encounter with Bon, the older religion of Tibet, an animistic religion that emphasized shamans, rituals to invoke and appease spirits, and even sacrifices.2 Together, these produce a Buddhism centered on monks and monasteries that is “more colorful and supernatural”3 than other forms such as Zen.4 This form of Buddhism emphasizes the place of the lama, or teacher, who directs his charges in their meditation and ritual practices. -

A Hackathon for Classical Tibetan

A Hackathon for Classical Tibetan Orna Almogi1, Lena Dankin2*, Nachum Dershowitz2,3, Lior Wolf2 1Universität Hamburg, Germany 2Tel Aviv University, Israel 3Institut d’Études Avancées de Paris, France *Corresponding author: Lena Dankin, [email protected] Abstract We describe the course of a hackathon dedicated to the development of linguistic tools for Tibetan Buddhist studies. Over a period of five days, a group of seventeen scholars, scientists, and students developed and compared algorithms for intertextual alignment and text classification, along with some basic language tools, including a stemmer and word segmenter. Keywords Tibetan; Buddhist studies; hackathon; stemming; segmentation; intertextual alignment; text classification. I INTRODUCTION In February 2016, a group of four Tibetologists (from the University of Hamburg), one digital humanities scholar (from Europe), and twelve computer scientists (from Israel and Europe) got together in Kibbutz Lotan in the Arava region of Israel with the stated goal of developing algorithmic methods for advancing Tibetan Buddhist textual studies. Participants were either recruited by the organizers or responded to an announcement on several mailing lists. See Figure 1. Most of the computer scientists had background in machine learning, and a few of them also had experience with natural language processing (NLP) research, but without any prior experience with Tibetan texts. The computer scientist organizers were quite familiar with programming workshops and contests and thought that the challenges presented by Tibetan texts would pose an ideal opportunity to explore the hackathon format. The hackathon is a short and intense event where computer scientists collaborate to develop software. For that purpose, it was essential to recruit as many software developers as possible. -

Chenrezig Practice

1 Chenrezig Practice Collected Notes Bodhi Path Natural Bridge, VA February 2013 These notes are meant for private use only. They cannot be reproduced, distributed or posted on electronic support without prior explicit authorization. Version 1.00 ©Tsony 2013/02 2 About Chenrezig © Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Heart Treasure of the Enlightened One. ISBN-10: 0877734933 ISBN-13: 978-0877734932 In the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon of enlightened beings, Chenrezig is renowned as the embodiment of the compassion of all the Buddhas, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Avalokiteshvara is the earthly manifestation of the self born, eternal Buddha, Amitabha. He guards this world in the interval between the historical Sakyamuni Buddha, and the next Buddha of the Future Maitreya. Chenrezig made a a vow that he would not rest until he had liberated all the beings in all the realms of suffering. After working diligently at this task for a very long time, he looked out and realized the immense number of miserable beings yet to be saved. Seeing this, he became despondent and his head split into thousands of pieces. Amitabha Buddha put the pieces back together as a body with very many arms and many heads, so that Chenrezig could work with myriad beings all at the same time. Sometimes Chenrezig is visualized with eleven heads, and a thousand arms fanned out around him. Chenrezig may be the most popular of all Buddhist deities, except for Buddha himself -- he is beloved throughout the Buddhist world. He is known by different names in different lands: as Avalokiteshvara in the ancient Sanskrit language of India, as Kuan-yin in China, as Kannon in Japan. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

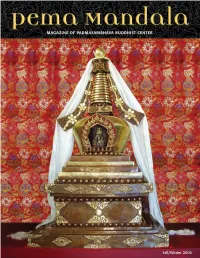

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Compassion & Social Justice

COMPASSION & SOCIAL JUSTICE Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo PUBLISHED BY Sakyadhita Yogyakarta, Indonesia © Copyright 2015 Karma Lekshe Tsomo No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the editor. CONTENTS PREFACE ix BUDDHIST WOMEN OF INDONESIA The New Space for Peranakan Chinese Woman in Late Colonial Indonesia: Tjoa Hin Hoaij in the Historiography of Buddhism 1 Yulianti Bhikkhuni Jinakumari and the Early Indonesian Buddhist Nuns 7 Medya Silvita Ibu Parvati: An Indonesian Buddhist Pioneer 13 Heru Suherman Lim Indonesian Women’s Roles in Buddhist Education 17 Bhiksuni Zong Kai Indonesian Women and Buddhist Social Service 22 Dian Pratiwi COMPASSION & INNER TRANSFORMATION The Rearranged Roles of Buddhist Nuns in the Modern Korean Sangha: A Case Study 2 of Practicing Compassion 25 Hyo Seok Sunim Vipassana and Pain: A Case Study of Taiwanese Female Buddhists Who Practice Vipassana 29 Shiou-Ding Shi Buddhist and Living with HIV: Two Life Stories from Taiwan 34 Wei-yi Cheng Teaching Dharma in Prison 43 Robina Courtin iii INDONESIAN BUDDHIST WOMEN IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Light of the Kilis: Our Javanese Bhikkhuni Foremothers 47 Bhikkhuni Tathaaloka Buddhist Women of Indonesia: Diversity and Social Justice 57 Karma Lekshe Tsomo Establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha in Indonesia: Obstacles and -

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora Beyond Tibet

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora beyond Tibet Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Dias- pora beyond Tibet.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 7–32. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/uranchimeg. Abstract This article discusses a Khalkha reincarnate ruler, the First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar, who is commonly believed to be a Géluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Za- nabazar’s Géluk affiliation, however, is a later Qing-Géluk construct to divert the initial Khalkha vision of him as a reincarnation of the Jonang historian Tāranātha (1575–1634). Whereas several scholars have discussed the political significance of Zanabazar’s rein- carnation based only on textual sources, this article takes an interdisciplinary approach to discuss, in addition to textual sources, visual records that include Zanabazar’s por- traits and current findings from an ongoing excavation of Zanabazar’s Saridag Monas- tery. Clay sculptures and Zanabazar’s own writings, heretofore little studied, suggest that Zanabazar’s open approach to sectarian affiliations and his vision, akin to Tsongkhapa’s, were inclusive of several traditions rather than being limited to a single one. Keywords: Zanabazar, Géluk school, Fifth Dalai Lama, Jebtsundampa, Khalkha, Mongo- lia, Dzungar Galdan Boshogtu, Saridag Monastery, archeology, excavation The First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar (1635–1723) was the most important protagonist in the later dissemination of Buddhism in Mongolia. Unlike the Mongol imperial period, when the sectarian alliance with the Sakya (Tib. -

The Nine Yanas

The Nine Yanas By Cortland Dahl In the Nyingma school, the spiritual journey is framed as a progression through nine spiritual approaches, which are typically referred to as "vehicles" or "yanas." The first three yanas include the Buddha’s more accessible teachings, those of the Sutrayana, or Sutra Vehicle. The latter six vehicles contain the teachings of Buddhist tantra and are referred to as the Vajrayana, or Vajra Vehicle. Students of the Nyingma teachings practice these various approaches as a unity. Lower vehicles are not dispensed with in favor of supposedly “higher” teachings, but rather integrated into a more refined and holistic approach to spiritual development. Thus, core teachings like renunciation and compassion are equally important in all nine vehicles, though they may be expressed in more subtle ways. In the Foundational Vehicle, for instance, renunciation involves leaving behind “worldly” activities and taking up the life of a celibate monk or nun, while in the Great Perfection, renunciation means to leave behind all dualistic perception and contrived spiritual effort. Each vehicle contains three distinct components: view, meditation, and conduct. The view refers to a set of philosophical tenets espoused by a particular approach. On a more experiential level, the view prescribes how practitioners of a given vehicle should “see” reality and its relative manifestations. Meditation consists of the practical techniques that allow practitioners to integrate Buddhist principles with their own lives, thus providing a bridge between theory and experience, while conduct spells out the ethical guidelines of each system. The following sections outline the features of each approach. Keep in mind, however, that each vehicle is a world unto itself, with its own unique philosophical views, meditations, and ethical systems. -

Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Blog Al Jazeera Top Story

Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Blog: Al Jazeera Top Story -- Revisits Court Case against the Dalai Lama 1/15/09 12:32 PM Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Blog The official blog of the Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Website, providing the latest news, videos, and updates on the Dorje Shugden controversy. WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 14, 2009 Subscribe Al Jazeera Top Story -- Revisits Court Case against Posts the Dalai Lama Comments Al Jazeera’s People and Power has named ‘The Dalai Lama: The Devil Within’ one of their top two stories of 2008. As a result, Al Jazeera is now Protector of Je featuring it again. Tsongkhapa's Tradition The reporter has added at the end of the updated report: "The case against the Dalai Lama is still with the courts. We hope to bring you an update later in the year." As the lawyer for the persecuted Shugden practitioners, Shree Sanjay Jain, explains: "It is certainly a case of religious discrimination in the sense that if within your sect of religion you say that this particular Deity ought not to be worshipped, and those persons who are willing to worship him you are trying to excommunicate them from the main stream of Buddhism, then it is a discrimination of worst kind." Al Jazeera adds: "No matter what the outcome of the court case, in a country Click on picture for Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden where millions of idols are worshipped, attempting to ban the Website Deity is an uphill battle. One in which many Buddhist monks have lost their faith in the spirit of the Dalai Lama." Search For a full transcript, see Al Jazeera News Documentary, October 2008. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4.