Original W.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Was Who in Early Modern Limerick by Alan O'driscoll and Brian Hodkinson

Who Was Who in Early Modern Limerick By Alan O'Driscoll and Brian Hodkinson The following was commenced by Alan O’Driscoll (AOD) while on a work placement in Limerick Museum in the autumn of 2012 and continued by Brian Hodkinson. It is a continuation of the Who was who in medieval Limerick, which can also be found on the Limerick Museum website. It straddles the period c 1540 to c 1700, so some figures may appear in both databases. It is compiled for the most part by using the indexes of the various sources using Limerick as the search term. However, it has been noted that these indexes are often not comprehensive, and so when sources are available online, then a scroll through the text highlighting Limerick has produced entries not in the index. Such scrolling has also found entries where place names are abviously Limerick ones but Limerick does not appear as a word, e.g. in Fiants and CPCRCI. So while I (BJH) like to think it is comprehensive, it may not be. Notes. • Where two similar names are believed to be the same person, the entries are combined. However, many repeated names appear in the same lists (particularly in the Civil Survey). Where this occurs and/or the two persons are listed as coming from a different location, they are separated, even if they are recorded at the same time. There are a great many repeated full names, such as William Bourke, and it has proved practically impossible to be sure of which of these are different people. -

BMH.WS1721.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1721. Witness Seumas Robinson 18 Highfield Foad, Rathgar, Dublin. Identity. O/C. South Tipperary Brigade. O/C. 2nd Southern Division, I.R.A. Member of Volunteer Executive. Member of Bureau of Military History. Subject. Irish Volunteer activities, Dublin, 1916. I.R.A.activities, Tipperary, 1917-1921 Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.132. Form BSM2 SEUMASROBINSON. 1902. Joined the first Fianna (Red Branch Knights); founded by Bulmer Hobson in 1902, Belfast. 1902. Joined "Oscar" junior hurling club, Belfast. 1903. Joined Gaelic League, Glasgow. 1913. December. Joined the Irish Volunteers, (Glasgow. 1916. January. Attached to Kimmage Garrison. 1916. Easter Week. Stationed i/c. at Hopkins & Hopkins, O'Connell Street (Bride). 1916. May. Interned Richmond Barracks (one week), Stafford Gaol, Frongoch, Reading Gaol. Released Christmas Day, 1916. 1917. February. Assisted in reorganising the Volunteers in Tipperary. l9l8. October, Elected Brigadier, South Tipperary Brigade. 1920. Elected T.D. to Second Dáil, East Tipperary and Waterford. 1921. November December. Appointed O/C., 2nd Southern Division, I.R.A., in succession to E. O'Malley. 1922. Elected Member of Volunteer Executive. l928. Elected Senator. 1935. January. Appointed Member of M.S.P. Board. l949. Appointed Member, Bureau of Military History. 1953. (?) Appointed Member of Military Registration Board. STATEMENTBY Mr. SEUMASROBINSON, 18, Highfield Road, Rathgar, Dublin. - Introduction - "A SOLDIER OF IRELAND" REFLECTS. Somewhere deep in the camera (or is it the anti-camera) of my cerebrum (or is it my cerebellum"), whose loci, by the way, are the frontal lobes of the cranium of this and every other specimen of homo-sapiens - there lurks furtively and nebulously, nevertheless positively, a thing, a something, a conception (deception'), a perception, an inception, that the following agglomeration of reminiscences will be "my last Will and Testament". -

The O'keeffes of Glenough by Robert O'keeffe Nora O'keeffe Was Born In

The O’Keeffes of Glenough by Robert O’Keeffe Nora O’Keeffe was born in Glenough, Rossmore Co. Tipperary in 1885, and was one of 12 children. The family were steeped in the nationalist tradition and her father, Dan, was a Nationalist Justice of Peace and a respected nationalist figure locally. There are uncorroborated stories of involvement in the Fenian outbreak of 1867 (Fr Denis Matthew O’Keeffe’s history). Nora emigrated to the US in 1909 and worked as a typist/stenographer. She appears to have returned to Ireland in 1918/9 along with her brother Patrick. During her time in the US she appears to have met Margaret Skinnider with whom it is thought she had a life long same sex relationship. (McAuliffe) She became active with Cumann na mBan and was among those listed in Bureau of Military History statements as having dispersed the gelignite from the Sologheadbeg ambush across the Brigade area. The younger members of the family seem to have immersed themselves in the national struggle at this time. This was probably due in no small part to the presence in the locality of staunch Republicans such as Fr Matt Ryan of Knockavilla, Eamonn O’Duibhir of Ballagh and the Irish teacher, Padraig Breathnach. The house at Glenough was used as a safe house and also played host to brigade meetings. The “Big Four” of Robinson, Breen, Treacy and Hogan were regular visitors as was Ernie O’Malley. O’Malley mentions the family in his autobiography “On another man’s wound” and also in his book “Raids and Rallies”. -

BMH.WS1412.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1412. Witness Michael Hennessy, Dundrum, Co. Tipperary. Identity. Member of East Limerick Brigade Flying Column. Subject. Activities of Kilfinane Company, Irish Volunteers, l914-1921, and East Limerick Flying Column, 1920-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.2740. Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY MR. MICHAEL HENNESSY, Dundrum,Co. Tipperary. I joined the Irish Volunteers when a company of that organisation was formed in my native place of Kilfinane, Co. Limerick, towards the end of the year of l914. I was then about twenty-one years of age. There were about thirty young men in the company, and Sean McCarthy, then resident in Kilfinane, was the company 0/C. Justin McCarthy, Sean's cousin, and Dan McCarthy were the other two officers of the company. We paraded about once or twice a week for training and drill. Foot drill was practised in a field near the town, and occasionally we went on route marches to places like Ballylanders and Glenbrohane. The training was done with wooden guns and, as far as I am aware, the company at that time possessed no effective arms. I should also mention that our company the Kilfinane company as it was then known was attached to the Galtee battalion of which, if my memory serves me right, Willie Manahan, then the creamery manager in Ardpatrick, was 0/C. My recollection of Easter Week 1916 is that the company was mobilised to parade on either Easter Sunday or Easter Monday morning, and each man was instructed to bring sufficient rations to maintain him for a couple of days. -

Limerick Timetables

Limerick B A For more information For online information please visit: locallinklimerick.ie Call us at: 069 78040 Email us at: [email protected] Ask your driver or other staff member for assistance Operated By: Local Link Limerick Fares: Adult Return/Single: €5.00/€3.00 Student & Child Return/Single: €3.00/€2.00 Adult Train Connector: €1.50 Student/Child Train Connector: €1.00 Multi Trip Adult/Child: €8.00/€5.00 Weekly Student/Child: €12.00 5 day Weekly Adult: €20.00 6 day Weekly Adult: €25.00 Free Travel Pass holders and children under 5 years travel free Our vehicles are wheelchair accessible Contents Route Page Ballyorgan – Ardpatrick – Kilmallock – Charleville – Doneraile 4 Newcastle West Service (via Glin & Shanagolden) 12 Charleville Child & Family Education Centre 20 Spa Road Kilfinane to Mitchelstown 21 Mountcollins to Newcastle West (via Dromtrasna) 23 Athea Shanagolden to Newcastle West Desmond complex 24 Castlemahon via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 25 Castlmahon to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 26 Ballykenny to Newcastle West- Desmond Complex 27 Shanagolden to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 28 Tournafulla to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 29 Abbeyfeale to Newcastle West - Special Olympics 30 Elton to Hospital 31 Adare to Newcastle West 32 Kilfinny via Adare to Newcastle West 33 Feenagh via Ballingarry to Newcastle West - Desmond Complex 34 Knockane via Patrickswell to Dooradoyle 35 Knocklong to Dooradoyle 36 Rathkeale via Askeaton to Newcastle West to Desmond Complex 37 Ballingarry to -

A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969

ireiana Edward Norman I Edward Norman A History of Modem Ireland 1800-1969 Advisory Editor J. H. Plumb PENGUIN BOOKS 1971 Contents Preface to the Pelican Edition 7 1. Irish Questions and English Answers 9 2. The Union 29 3. O'Connell and Radicalism 53 4. Radicalism and Reform 76 5. The Genesis of Modern Irish Nationalism 108 6. Experiment and Rebellion 138 7. The Failure of the Tiberal Alliance 170 8. Parnellism 196 9. Consolidation and Dissent 221 10. The Revolution 254 11. The Divided Nation 289 Note on Further Reading 315 Index 323 Pelican Books A History of Modern Ireland 1800-1969 Edward Norman is lecturer in modern British constitutional and ecclesiastical history at the University of Cambridge, Dean of Peterhouse, Cambridge, a Church of England clergyman and an assistant chaplain to a hospital. His publications include a book on religion in America and Canada, The Conscience of the State in North America, The Early Development of Irish Society, Anti-Catholicism in 'Victorian England and The Catholic Church and Ireland. Edward Norman also contributes articles on religious topics to the Spectator. Preface to the Pelican Edition This book is intended as an introduction to the political history of Ireland in modern times. It was commissioned - and most of it was actually written - before the present disturbances fell upon the country. It was unfortunate that its publication in 1971 coincided with a moment of extreme controversy, be¬ cause it was intended to provide a cool look at the unhappy divisions of Ireland. Instead of assuming the structure of interpretation imposed by writers soaked in Irish national feeling, or dependent upon them, the book tried to consider Ireland’s political development as a part of the general evolu¬ tion of British politics in the last two hundred years. -

Limerick Walking Trails

11. BALLYHOURA WAY 13. Darragh Hills & B F The Ballyhoura Way, which is a 90km way-marked trail, is part of the O’Sullivan Beara Trail. The Way stretches from C John’s Bridge in north Cork to Limerick Junction in County Tipperary, and is essentially a fairly short, easy, low-level Castlegale LOOP route. It’s a varied route which takes you through pastureland of the Golden Vale, along forest trails, driving paths Trailhead: Ballinaboola Woods Situated in the southwest region of Ireland, on the borders of counties Tipperary, Limerick and Cork, Ballyhoura and river bank, across the wooded Ballyhoura Mountains and through the Glen of Aherlow. Country is an area of undulating green pastures, woodlands, hills and mountains. The Darragh Hills, situated to the A Car Park, Ardpatrick, County southeast of Kilfinnane, offer pleasant walking through mixed broadleaf and conifer woodland with some heathland. Directions to trailhead Limerick C The Ballyhoura Way is best accessed at one of seven key trailheads, which provide information map boards and There are wonderful views of the rolling hills of the surrounding countryside with Galtymore in the distance. car parking. These are located reasonably close to other services and facilities, such as shops, accommodation, Services: Ardpatrick (4Km) D Directions to trailhead E restaurants and public transport. The trailheads are located as follows: Dist/Time: Knockduv Loop 5km/ From Kilmallock take the R512, follow past Ballingaddy Church and take the first turn to the left to the R517. Follow Trailhead 1 – John’s Bridge Ballinaboola 10km the R517 south to Kilfinnane. At the Cross Roads in Kilfinnane, turn right and continue on the R517. -

Limerick Manual

RECORD OF MONUMENTSAND PLACES as Established under Section 12 of the National Monuments ’ (Amendment)Act 1994 COUNTYLIMERICK Issued By National Monumentsand Historic Properties Service 1997 j~ Establishment and Exhibition of Record of Monumentsand Places under Section 12 of the National Monuments (Amendment)Act 1994 Section 12 (1) of the National Monuments(Amendment) Act 1994 states that Commissionersof Public Worksin Ireland "shall establish and maintain a record of monumentsand places where they believe there are monumentsand the record shall be comprised of a list of monumentsand such places and a mapor mapsshowing each monumentand such place in respect of each county in the State." Section 12 (2) of the Act provides for the exhibition in each county of the list and mapsfor that county in a mannerprescribed by regulations madeby the Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht. The relevant regulations were made under Statutory Instrument No. 341 of 1994, entitled National Monuments(Exhibitior~ of Record of Monuments)Regulations, 1994. This manualcontains the list of monumentsand places recorded under Section 12 (1) of the Act for the Countyof Limerick whichis exhibited along with the set of mapsfor the Countyof Limerick showingthe recorded monumentsand places. Protection of Monumentsand Places included in the Record Section 12 (3) of the Act provides for the protection of monumentsand places included in the record stating that "When the owner or occupier (not being the Commissioners) of monumentor place which has been recorded under -

1911 Census, Co. Limerick Householder Index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish

W - 1911 Census, Co. Limerick householder index Surname Forename Townland Civil Parish Corresponding RC Parish Wade Henry Turagh Tuogh Cappamore Wade John Cahernarry (Cripps) Cahernarry Donaghmore Wade Joseph Drombanny Cahernarry Donaghmore Wakely Ellen Creagh Street, Glin Kilfergus Glin Walker Arthur Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Catherine Blossomhill, Pt. of Rathkeale Rathkeale (Rural) Walker George Rooskagh East Ardagh Ardagh Walker Henry Askeaton Askeaton Askeaton Walker Mary Bishop Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker Thomas Church Street, Newcastle Newcastle Newcastle West Walker William Adare Adare Adare Walker William F. Blackabbey Adare Adare Wall Daniel Clashganniff Kilmoylan Shanagolden Wall David Cloon and Commons Stradbally Castleconnell Wall Edmond Ballygubba South Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall Edward Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Edward Ballingarry Ballingarry Ballingarry Wall Ellen Aughinish East Robertstown Shanagolden Wall Ellen Ballynacourty Iveruss Askeaton Wall James Abbeyfeale Town Abbeyfeale Abbeyfeale Wall James Ballycullane St. Peter & Paul's Kilmallock Wall James Bruff Town Bruff Bruff Wall James Mundellihy Dromcolliher Drumcolliher, Broadford Wall Johanna Callohow Cloncrew Drumcollogher Wall John Aughalin Clonelty Knockderry Wall John Ballycormick Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ballygubba North Tankardstown Kilmallock Wall John Clashganniff Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes Wall John Ranahan Rathkeale Rathkeale Wall John Shanagolden Town Shanagolden Shanagolden & Foynes -

Cultural Heritage Iarnród Éireann

Cork Line Level Crossings Volume 3, Chapter 12: Cultural Heritage Iarnród Éireann March 2021 EIAR Chapter 12 C ultural H eritage Iarnr ód Éir eann Volume 3, Chapter 12: Cultural Heritage Cork Line Level Crossings Project No: 32111000 Document Title: EIAR Chapter 12 Cultural Heritage Document No. 12 Revision: A04 Date: March 2021 Client Name: Iarnród Éireann Project Manager: Alex Bradley Author: AMS Ltd Jacobs U.K. Limited Artola House 3rd & 4th Floors 91 Victoria Street Belfast BT1 4PN T +44 (0)28 9032 4452 F +44 (0)28 9033 0713 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2021 Jacobs U.K. Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description Author Checked Reviewed Approved A01 December Client Review AMS AMS RM AB 2019 A02 November Interim Draft pending Archaeological AMS HC HC AB 2020 Investigations A03 March Final draft AMS AMS RM AB 2021 A04 March For Issue to An Bord Pleanála AMS AMS HC/RM AB 2021 i Volume 3, Chapter 12: Cultural Heritage Contents 12. Cultural Heritage ................................................................................................................................................... -

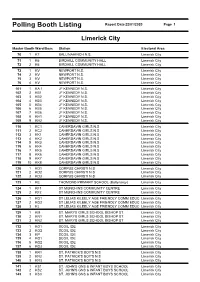

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1 Limerick City Master Booth Ward/Desc Station Electoral Area 70 1 K7 BALLINAHINCH N.S. Limerick City 71 1 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 72 2 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 73 1 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 74 2 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 75 3 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 76 4 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 101 1 KA.1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 102 2 KB1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 103 3 KB2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 104 4 KB3 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 105 5 KB4 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 106 6 KB5 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 107 7 KB6 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 108 8 KH1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 109 9 KH2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 110 1 KC1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 111 2 KC2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 112 3 KK1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 113 4 KK2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 114 5 KK3 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 115 6 KK4 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 116 7 KK5 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 117 8 KK6 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 118 9 KK7 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 119 10 KK8 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 120 1 KD1 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 121 2 KD2 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 122 3 KD3 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 123 1 KE THOMOND PRIMARY SCHOOL (Ballynanty) Limerick City 124 1 KF1 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 125 2 KF2 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 126 1 KG1 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 127 2 KG2 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 128 3 KJ ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 129 1 KM ST. -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 883 Witness Lieut. -Col. John M. MacCarthy, 225, Cabra Road, Phibsborough, Dublin. Identity. Adjutant, East Limerick Brigade; Member of East Limerick Flying Column. Subject. National and military activities, East Limerick, 1900-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.523 Form B.S.M.2 Statement of Lieut-Colonel J.M. MacCarthy. CONTENTS. Pages 1. Family background and the national orientation in Kilfinnane in the early years of the century. 1-4 2. Schooldays - Clongowes & St. Colman's, Fermoy. 5-6 The: Volunteer movement in Kilfinnane from to the 3. 1914 Redmondite Spilt. 6-12 The Irish Volunteers after the: 4. Re-organised Split with the? assistance of Ernest Blythe: as the G.H.Q. organiser. The: formation of the Galtee. Battalion. 12-14 5. Galtee training camp under Ginger O'Connell in summer of 1915 - subsequent camp at Kilkee. 15-1614-15 The: 1915 Whit parade in Limerick. 6.7. Proposal to arm Volunteers with pikes. 17 Easter Week 18-23 8. 1916. The 9. Re-organisation and the Manahan-Hannigan Split and the enquiry. 25-28 10. Sean Wall. as the: Brigade Commander in East Limerick - his death in 1921. 28-30 The crises 30-32 11. Conscription period The: africars of the (Galtee) Battn. 32-34 12. re-organised 5th The elections - induct ion into the I.R.B. 13. 1918 My 34-35 Reference. to the rescue: of Sean Hogan at 14. Knocklong Station. 35-37 Reference ta the Limerick.