Colonization of Venus from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Venus Aerobot Multisonde Mission

w AIAA Balloon Technology Conference 1999 Venus Aerobot Multisonde Mission By: James A. Cutts ('), Viktor Kerzhanovich o_ j. (Bob) Balaram o), Bruce Campbell (2), Robert Gershman o), Ronald Greeley o), Jeffery L. Hall ('), Jonathan Cameron o), Kenneth Klaasen v) and David M. Hansen o) ABSTRACT requires an orbital relay system that significantly Robotic exploration of Venus presents many increases the overall mission cost. The Venus challenges because of the thick atmosphere and Aerobot Multisonde (VAMuS) Mission concept the high surface temperatures. The Venus (Fig 1 (b) provides many of the scientific Aerobot Multisonde mission concept addresses capabilities of the VGA, with existing these challenges by using a robotic balloon or technology and without requiring an orbital aerobot to deploy a number of short lifetime relay. It uses autonomous floating stations probes or sondes to acquire images of the (aerobots) to deploy multiple dropsondes capable surface. A Venus aerobot is not only a good of operating for less than an hour in the hot lower platform for precision deployment of sondes but atmosphere of Venus. The dropsondes, hereafter is very effective at recovering high rate data. This described simply as sondes, acquire high paper describes the Venus Aerobot Multisonde resolution observations of the Venus surface concept and discusses a proposal to NASA's including imaging from a sufficiently close range Discovery program using the concept for a that atmospheric obscuration is not a major Venus Exploration of Volcanoes and concern and communicate these data to the Atmosphere (VEVA). The status of the balloon floating stations from where they are relayed to deployment and inflation, balloon envelope, Earth. -

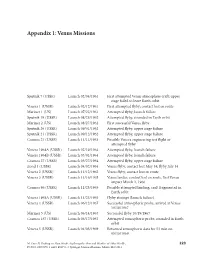

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

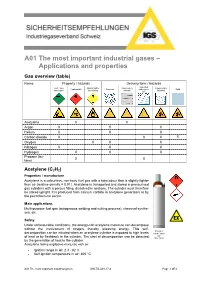

A01 the Most Important Industrial Gases – Applications and Properties

A01 The most important industrial gases – Applications and properties Gas overview (table) Name Property / hazards Delivery form / hazards Liquefied Inert / non- Oxidising/fire Dissolved (in Cryogenically Combustible Gaseous under pres- Solid flammable intensifying solvent) liquefied sure Acetylene X X Argon X X X Helium X X X Carbon dioxide X X X X Oxygen X X X Nitrogen X X X Hydrogen X X X Propane (bu- X X tane) Acetylene (C2H2) Properties / manufacture Acetylene is a colourless, non-toxic fuel gas with a faint odour that is slightly lighter than air (relative density = 0.91). Acetylene is transported and stored in pressurised gas cylinders with a porous filling, dissolved in acetone. The cylinder must therefore be stored upright. It is produced from calcium carbide in acetylene generators or by the petrochemical sector. Main applications Multi-purpose fuel gas (autogenous welding and cutting process), chemical synthe- ses, etc. Safety Under unfavourable conditions, the energy-rich acetylene molecule can decompose without the involvement of oxygen, thereby releasing energy. This self- Shoulder decomposition can be initiated when an acetylene cylinder is exposed to high levels colour “oxide red” of heat or by flashback in the cylinder. The start of decomposition can be detected RAL 3009 by the generation of heat in the cylinder. Acetylene forms explosive mixtures with air. Ignition range in air: 2.3 - 82 % Self-ignition temperature in air: 305 °C A01 The most important industrial gases IGS-TS-A01-17-d Page 1 of 4 Argon (Ar) Properties / manufacture Argon is a colourless, odourless, non-combustible gas, extremely inert noble gas and heavier than air (relative density = 1.78). -

Pathways to Colonization David V

Pathways To Colonization David V. Smitherman, Jr. NASA, Marshall Space F’light Center, Mail CoLFDO2, Huntsville, AL 35812,256-961-7585, Abstract. The steps required for space colonization are many to grow fiom our current 3-person International Space Station,now under construction, to an inhstmcture that can support hundreds and eventually thousands of people in space. This paper will summarize the author’s fmdings fiom numerous studies and workshops on related subjects and identify some of the critical next steps toward space colonization. Findings will be drawn from the author’s previous work on space colony design, space infirastructure workshops, and various studies that addressed space policy. In cmclusion, this paper will note that siBnifcant progress has been made on space facility construction through the International Space Station program, and that si&icant efforts are needed in the development of new reusable Earth to Orbit transportation systems. The next key steps will include reusable in space transportation systems supported by in space propellant depots, the continued development of inflatable habitat and space elevator technologies, and the resolution of policy issues that will establish a future vision for space development A PATH TO SPACE COLONIZATION In 1993, as part of the author’s duties as a space program planner at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, a lengthy timeline was begun to determine the approximate length of time it might take for humans to eventually leave this solar system and travel to the stars. The thought was that we would soon discover a blue planet around another star and would eventually seek to send a colony to explore and expand our presence in this galaxy. -

Colonization of Venus

Conference on Human Space Exploration, Space Technology & Applications International Forum, Albuquerque, NM, Feb. 2-6 2003. Colonization of Venus Geoffrey A. Landis NASA Glenn Research Center mailstop 302-1 21000 Brook Park Road Cleveland, OH 44135 21 6-433-2238 geofrq.landis@grc. nasa.gov ABSTRACT Although the surface of Venus is an extremely hostile environment, at about 50 kilometers above the surface the atmosphere of Venus is the most earthlike environment (other than Earth itself) in the solar system. It is proposed here that in the near term, human exploration of Venus could take place from aerostat vehicles in the atmosphere, and that in the long term, permanent settlements could be made in the form of cities designed to float at about fifty kilometer altitude in the atmosphere of Venus. INTRODUCTION Since Gerard K. O'Neill [1974, 19761 first did a detailed analysis of the concept of a self-sufficient space colony, the concept of a human colony that is not located on the surface of a planet has been a major topic of discussion in the space community. There are many possible economic justifications for such a space colony, including use as living quarters for a factory producing industrial products (such as solar power satellites) in space, and as a staging point for asteroid mining [Lewis 19971. However, while the concept has focussed on the idea of colonies in free space, there are several disadvantages in colonizing empty space. Space is short on most of the raw materials needed to sustain human life, and most particularly in the elements oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen. -

Risks of Space Colonization

Risks of space colonization Marko Kovic∗ July 2020 Abstract Space colonization is humankind's best bet for long-term survival. This makes the expected moral value of space colonization immense. However, colonizing space also creates risks | risks whose potential harm could easily overshadow all the benefits of humankind's long- term future. In this article, I present a preliminary overview of some major risks of space colonization: Prioritization risks, aberration risks, and conflict risks. Each of these risk types contains risks that can create enormous disvalue; in some cases orders of magnitude more disvalue than all the potential positive value humankind could have. From a (weakly) negative, suffering-focused utilitarian view, we there- fore have the obligation to mitigate space colonization-related risks and make space colonization as safe as possible. In order to do so, we need to start working on real-world space colonization governance. Given the near total lack of progress in the domain of space gover- nance in recent decades, however, it is uncertain whether meaningful space colonization governance can be established in the near future, and before it is too late. ∗[email protected] 1 1 Introduction: The value of colonizing space Space colonization, the establishment of permanent human habitats beyond Earth, has been the object of both popular speculation and scientific inquiry for decades. The idea of space colonization has an almost poetic quality: Space is the next great frontier, the next great leap for humankind, that we hope to eventually conquer through our force of will and our ingenuity. From a more prosaic point of view, space colonization is important because it represents a long-term survival strategy for humankind1. -

Activity Guide: Space Colony Build

Activity Guide: Space Colony Build Purpose: Grades 3-5 Museum Connection: Space Odyssey’s Mars Diorama gives a unique opportunity to talk to someone that lives on Mars and ask what it takes to make a colony there! Diorama halls also offer opportunities to review the basic needs for living things. Main Idea: To build a colony that could sustain human life on Mars or anywhere in space. Individuals/groups should be challenged to create a plan ahead of building, including where their colony is located in space. Background Information for Educator: As concerns around the habitability of Earth continue to grow, researchers are looking to space colonization as a possible solution. This presents opportunities to dream about what life in space would be like. Some of the first problems to face are the effects of weightlessness on the body and exposure to radiation living outside of the Earth’s protective atmosphere. Other challenges in space to consider are cultivating and sustaining basic human needs of air, water, food, and shelter. Living in space could also offer other potential benefits not found on Earth, including unlimited access to solar power or using weightlessness to our advantage. Independent companies are beginning to look at how to get to space and how to sustain colonies there. Sources: Space Colonization & Resources Prep (5-10 Minutes): Gather materials to build. Can be a mixture of Keva Planks, recyclables, and/or anything you want guests to use. Decide if guests will work in groups. Make sure the space to be used for the build is open, clear, and ready for use. -

Simulating Crowds Based on a Space Colonization Algorithm

Computers & Graphics 36 (2012) 70–79 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Computers & Graphics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cag Virtual Reality in Brazil 2011 Simulating crowds based on a space colonization algorithm Alessandro de Lima Bicho a, Rafael Arau´ jo Rodrigues b, Soraia Raupp Musse b, Cla´udio Rosito Jung c,n, Marcelo Paravisi b,Le´o Pini Magalhaes~ d a Universidade Federal do Rio Grande—FURG, RS, Brazil b Pontifı´cia Universidade Cato´lica do Rio Grande do Sul—PUCRS, RS, Brazil c Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul—UFRGS, RS, Brazil d Universidade Estadual de Campinas—UNICAMP, SP, Brazil article info abstract Article history: This paper presents a method for crowd simulation based on a biologically motivated space Received 9 June 2011 colonization algorithm. This algorithm was originally introduced to model leaf venation patterns and Received in revised form the branching architecture of trees. It operates by simulating the competition for space between 30 November 2011 growing veins or branches. Adapted to crowd modeling, the space colonization algorithm focuses on Accepted 5 December 2011 the competition for space among moving agents. Several behaviors observed in real crowds, including Available online 23 December 2011 collision avoidance, relationship of crowd density and speed of agents, and the formation of lanes in Keywords: which people follow each other, are emergent properties of the algorithm. The proposed crowd Crowd simulation modeling method is free-of-collision, simple to implement, robust, computationally efficient, and Virtual humans suited to the interactive control of simulated crowds. Space colonization & 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. -

2013 News Archive

Sep 4, 2013 America’s Challenge Teams Prepare for Cross-Country Adventure Eighteenth Race Set for October 5 Launch Experienced and formidable. That describes the field for the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta’s 18th America’s Challenge distance race for gas balloons. The ten members of the five teams have a combined 110 years of experience flying in the America’s Challenge, along with dozens of competitive years in the other great distance race, the Coupe Aéronautique Gordon Bennett. Three of the five teams include former America’s Challenge winners. The object of the America’s Challenge is to fly the greatest distance from Albuquerque while competing within the event rules. The balloonists often stay aloft more than two days and must use the winds aloft and weather systems to their best advantage to gain the greatest distance. Flights of more than 1,000 miles are not unusual, and the winners sometimes travel as far as Canada and the U.S. East Coast. This year’s competitors are: • Mark Sullivan and Cheri White, USA: Last year Sullivan, from Albuquerque, and White, from Austin, TX, flew to Beauville, North Carolina to win their second America’s Challenge (their first was in 2008). Their winning 2012 flight of 2,623 km (1,626 miles) ended just short of the East Coast and was the fourth longest in the history of the race. The team has finished as high as third in the Coupe Gordon Bennett (2009). Mark Sullivan, a multiple-award-winning competitor in both hot air and gas balloons and the American delegate to the world ballooning federation, is the founder of the America’s Challenge. -

Humanity and Space Design and Implementation of a Theoretical Martian Outpost

Project Number: MH-1605 Humanity and Space Design and implementation of a theoretical Martian outpost An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute In partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Degree of Bachelor Science By Kenneth Fong Andrew Kelly Owen McGrath Kenneth Quartuccio Matej Zampach Abstract Over the next century, humanity will be faced with the challenge of journeying to and inhabiting the solar system. This endeavor carries many complications not yet addressed such as shielding from radiation, generating power, obtaining water, creating oxygen, and cultivating food. Still, practical solutions can be implemented and missions accomplished utilizing futuristic technology. With resources transported from Earth or gathered from Space, a semi-permanent facility can realistically be established on Mars. 2 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Introduction 3 2.1 Kenneth Fong . .4 2.2 Andrew Kelly . .6 2.3 Owen McGrath . .7 2.4 Kenneth Quartuccio . .8 2.5 Matej Zampach . .9 3 Research 10 3.1 Current Space Policy . 11 3.1.1 US Space Policy . 11 3.1.2 Russian Space Policy . 12 3.1.3 Chinese Space Policy . 12 3.2 Propulsion Methods . 14 3.2.1 Launch Loops . 14 3.2.2 Solar Sails . 17 3.2.3 Ionic Propulsion . 19 3.2.4 Space Elevator . 20 i 3.2.5 Chemical Propulsion . 21 3.3 Colonization . 24 3.3.1 Farming . 24 3.3.2 Sustainable Habitats . 25 3.3.3 Sustainability . 27 3.3.4 Social Issues . 28 3.3.5 Terraforming . 29 3.3.6 Harvesting Water from Mars . -

DAVINCI: Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Lori S

DAVINCI: Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Lori S. Glaze, James B. Garvin, Brent Robertson, Natasha M. Johnson, Michael J. Amato, Jessica Thompson, Colby Goodloe, Dave Everett and the DAVINCI Team NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 690 8800 Greenbelt Road Greenbelt, MD 20771 301-614-6466 Lori.S.Glaze@ nasa.gov Abstract—DAVINCI is one of five Discovery-class missions questions as framed by the NRC Planetary Decadal Survey selected by NASA in October 2015 for Phase A studies. and VEXAG, without the need to repeat them in future New Launching in November 2021 and arriving at Venus in June of Frontiers or other Venus missions. 2023, DAVINCI would be the first U.S. entry probe to target Venus’ atmosphere in 45 years. DAVINCI is designed to study The three major DAVINCI science objectives are: the chemical and isotopic composition of a complete cross- section of Venus’ atmosphere at a level of detail that has not • Atmospheric origin and evolution: Understand the been possible on earlier missions and to image the surface at origin of the Venus atmosphere, how it has evolved, optical wavelengths and process-relevant scales. and how and why it is different from the atmospheres of Earth and Mars. TABLE OF CONTENTS • Atmospheric composition and surface interaction: Understand the history of water on Venus and the 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1 chemical processes at work in the lower atmosphere. 2. MISSION DESIGN ..................................................... 2 • Surface properties: Provide insights into tectonic, 3. PAYLOAD ................................................................. 2 volcanic, and weathering history of a typical tessera 4. SUMMARY ................................................................ 3 (highlands) terrain. -

The Magellan Spacecraft at Venus by Andrew Fraknoi, Astronomical Society of the Pacific

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 18 - Fall 1991 © 1991, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. The Magellan Spacecraft at Venus by Andrew Fraknoi, Astronomical Society of the Pacific "Having finally penetrated below the clouds of Venus, we find its surface to be naked [not hidden], revealing the history of hundreds of millions of years of geological activity. Venus is a geologist's dream planet.'' —Astronomer David Morrison This fall, the brightest star-like object you can see in the eastern skies before dawn isn't a star at all — it's Venus, the second closest planet to the Sun. Because Venus is so similar in diameter and mass to our world, and also has a gaseous atmosphere, it has been called the Earth's "sister planet''. Many years ago, scientists expected its surface, which is perpetually hidden beneath a thick cloud layer, to look like Earth's as well. Earlier this century, some people even imagined that Venus was a hot, humid, swampy world populated by prehistoric creatures! But we now know Venus is very, very different. New radar images of Venus, just returned from NASA's Magellan spacecraft orbiting the planet, have provided astronomers the clearest view ever of its surface, revealing unique geological features, meteor impact craters, and evidence of volcanic eruptions different from any others found in the solar system. This issue of The Universe in the Classroom is devoted to what Magellan is teaching us today about our nearest neighbor, Venus. Where is Venus, and what is it like? Spacecraft exploration of Venus's surface Magellan — a "recycled'' spacecraft How does Magellan take pictures through the clouds? What has Magellan revealed about Venus? How does Venus' surface compare with Earth's? What is the next step in Magellan's mission? If Venus is such an uninviting place, why are we interested in it? Reading List Why is it so hot on Venus? Where is Venus, and what is it like? Venus orbits the Sun in a nearly circular path between Mercury and the Earth, about 3/4 as far from our star as the Earth is.