Malory's Guinevere As Structural Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 6-10-2019 The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur Marcos Morales II [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Cultural History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Morales II, Marcos, "The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur" (2019). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 276. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/276 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Creation of a King: How Geoffrey of Monmouth Influenced the Story of King Arthur. By: Marcos Morales II Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 05, 2019 Readers Professor Elizabeth Swedo Professor Bau Hwa Hsieh Copyright © Marcos Morales II Arthur, with a single division in which he had posted six thousand, six hundred, and sixty-six men, charged at the squadron where he knew Mordred was. They hacked a way through with their swords and Arthur continued to advance, inflicting terrible slaughter as he went. It was at this point that the accursed traitor was killed and many thousands of his men with him.1 With the inclusion of this feat between King Arthur and his enemies, Geoffrey of Monmouth shows Arthur as a mighty warrior, one who stops at nothing to defeat his foes. -

Echoes of Legend: Magic As the Bridge Between a Pagan Past And

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2018 Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur Josh Mangle Winthrop University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mangle, Josh, "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur" (2018). Graduate Theses. 84. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/84 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECHOES OF LEGEND: MAGIC AS THE BRIDGE BETWEEN A PAGAN PAST AND A CHRISTIAN FUTURE IN SIR THOMAS MALORY’S LE MORTE DARTHUR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of the College of Arts and Sciences In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts In English Winthrop University May 2018 By Josh Mangle ii Abstract Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur is a text that tells the story of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Malory wrote this tale by synthesizing various Arthurian sources, the most important of which being the Post-Vulgate cycle. Malory’s work features a division between the Christian realm of Camelot and the pagan forces trying to destroy it. -

Camelot the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Camelot The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Anne Newhall (left) as Billie Dawn and Craig Spidle as Harry Brock in Born Yesterday, 2003. Contents InformationCamelot on the Play Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play A Pygmalion Tale, but So Much More 8 Well in Advance of Its Time 10 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 8FTU$FOUFS4USFFUr $FEBS$JUZ 6UBIr Synopsis: Camelot On a frosty morning centuries ago in the magical kingdom of Camelot, King Arthur prepares to greet his promised bride, Guenevere. Merlyn the magician, the king’s lifelong mentor, finds Arthur, a reluctant king and even a more reluctant suitor, hiding in a tree. -

Camelot: Rules

Original Game Design: Tom Jolly Additional Game Design: Aldo Ghiozzi C a m e l o t : V a r i a t i o n R u l e s Playing Piece Art & Box Cover Art: The Fraim Brothers Game Board Art: Thomas Denmark Graphic Design & Box Bottom Art: Alvin Helms Playtesters: Rick Cunningham, Dan Andoetoe, Mike Murphy, A C C O U T R E M E N T S O F K I N G S H I P T H E G U A R D I A N S O F T H E S W O R D Dave Johnson, Pat Stapleton, Kristen Davis, Ray Lee, Nick Endsley, Nate Endsley, Mathew Tippets, Geoff Grigsby, Instead of playing to capture Excalibur, you can play In this version, put aside one of the 6 sets of tokens (or © 2005 by Tom Jolly Allan Sugarbaker, Matt Stipicevich, Mark Pentek and Aldo Ghiozzi to capture the Accoutrements of Kingship (hereafter make 2 new tokens for this purpose). Take two of the referred to as "Items") from the rest of the castle, Knights (Lancelots) from that set and place them efore there was King Arthur, there was… well, same time. Each player controls a small army of 15 returning the collected loot to your Entry. If you can within 2 spaces of Excalibur before the game starts. Arthur was a pretty common name back then, pieces, attempting to grab Excalibur from the claim any 2 of the 4 Items (the Crown, the Scepter, During the game, any player may move and attack with B since every mother wanted their little Arthur to center of the game board and return it to their the Robe, the Throne) one or both of these Knights, or use one of these be king, and frankly nobody really knew who "the real starting location. -

My Fair Lady

The Lincoln Center Theater Production of TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE Teacher Resource Guide by Sara Cooper TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 THE MUSICAL . 2 The Characters . 2 The Story . 2 The Writers, Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe . 5 The Adaptation of Pygmalion . 6 Classroom Activities . 7 THE BACKDROP . 9 Historical Context . 9 Glossary of Terms . 9 Language and Dialects in Musical Theater . 10 Classroom Activities…………… . 10 THE FORM . 13 Glossary of Musical Theater Terms . 13 Types of Songs in My Fair Lady . 14 The Structure of a Standard Verse-Chorus Song . 15 Classroom Activities . 17 EXPLORING THE THEMES . 18 BEHIND THE SCENES . 20 Interview with Jordan Donica . 20 Classroom Activities . 21 Resources . 22 INTRODUCTION Welcome to the teacher resource guide for My Fair Lady, a musical play in two acts with book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe, directed by Bartlett Sher. My Fair Lady is a musical adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion, itself an adaptation of an ancient Greek myth. My Fair Lady is the story of Eliza Doolittle, a penniless flower girl living in London in 1912. Eliza becomes the unwitting object of a bet between two upper-class men, phonetics professor Henry Higgins and linguist Colonel Pickering. Higgins bets that he can pass Eliza off as a lady at an upcoming high-society social event, but their relationship quickly becomes more complicated. In My Fair Lady, Lerner and Loewe explore topics of class discrimination, sexism, linguistic profiling, and social identity; issues that are still very much present in our world today. -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

Monty Python's SPAMALOT

Monty Python’s Spamalot CHARACTERS Please note that the ages listed just serve as a guide. All roles are available and casting is open, and newcomers are welcome and encouraged. Also, character doublings are only suggested here and may be changed based on audition results and production needs. KING ARTHUR (Baritone, Late 30s-60s) – The King of England, who sets out on a quest to form the Knights of the Round Table and find the Holy Grail. Great humor. Good singer. THE LADY OF THE LAKE (Alto with large range, 20s-40s) – A Diva. Strong, beautiful, possesses mystical powers. The leading lady of the show. Great singing voice is essential, as she must be able to sing effortlessly in many styles and vocal registers. Sings everything from opera to pop to scatting. Gets angry easily. SIR ROBIN (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. Ironically called "Sir Robin the Brave," though he couldn't be more cowardly. Joins the Knights for the singing and dancing. Also plays GUARD 1 and BROTHER MAYNARD, a long-winded monk. A good mover. SIR LANCELOT (Tenor/Baritone, 30s-40s) – A Knight of the Round Table. He is fearless to a bloody fault but through a twist of fate discovers his "softer side." This actor MUST be great with character voices and accents, as he also plays THE FRENCH TAUNTER, an arrogant, condescending, over-the-top Frenchman; the KNIGHT OF NI, an absurd, cartoonish leader of a peculiar group of Knights; and TIM THE ENCHANTER, a ghostly being with a Scottish accent. -

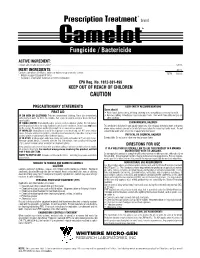

Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide

® Prescription Treatment brand Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Copper salts of fatty and rosin acids† . 58.0% INERT INGREDIENTS: . 42.0% Contains petroleum distillates, xylene or xylene range aromatic solvent. TOTAL 100.0% † Metallic Copper Equivalent 5.14%) * Camelot is a registered Trademark of Griffin Corporation. EPA Reg. No. 1812-381-499 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS USER SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS Users should: FIRST AID • Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. IF ON SKIN OR CLOTHING: Take off contaminated clothing. Rinse skin immediately • Remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on with plenty of water for 15 to 20 minutes. Call a poison control center or doctor for treat- clean clothing. ment advice. IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid This pesticide is toxic to fish and aquatic organisms. Do not apply directly to water, or to areas to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. where surface water is present or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambu- contaminate water when disposing of equipment washwaters. lance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice. PHYSICAL OR CHEMICAL HAZARDS IF IN EYES: Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15 to 20 minutes. -

The Duke: Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack

™ Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack The politics of the high courts are elegant, shadowy, and subtle. Fort Tile: Players can use the Fort Tile as shown on pages 7-8 of Not so in the outlying duchies. Rival dukes contend for unclaimed the rulebook for any game with these tiles. However, they can also lands far from the king’s reach, and possession is the law in these play with the reverse side of the Fort, Camelot. Camelot is an Ex- lands. Use your forces to adapt to your opponent’s strategies, cap- panded Play tile (see p. 6 of the rulebook) and so both players should turing enemy troops, before you lose your opportunity to seize these agree to its use before play begins. lands for your good. Randomly place Camelot in any square in one of the two middle In The Duke, players move their troops (tiles) around the board rows of the board. and flip them over after each move. Each tile’s side shows a different For the Arthur player, if one of his Arthurian Legends’ tiles is in- movement pattern. If you end your movement in a square occupied side Camelot (King Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, or Merlin), by an opponent’s tile, you capture that tile. Capture your opponent’s then the Camelot Tile gains Command ability in all eight squares Duke to win! surrounding Camelot. On his turn, any time those conditions are met, the player may use the Command ability of Camelot; the Troop ARTHurIan leGenDS EXPanSIon PacK RULES Tile on Camelot does not flip, but the Camelot Tile DOES flip over to Arthur, Guineviere, Merlin, Lancelot and Perceval replace the light the Fort side; as long as it’s on the Fort side, the Command ability no stained Duke, Duchess, Wizard, Champion and Assassin Tiles. -

Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart by Chrétien De Troyes

Lancelot, The Knight of the Cart by Chrétien de Troyes Translated by W. W. Comfort For your convenience, this text has been compiled into this PDF document by Camelot On-line. Please visit us on-line at: http://www.heroofcamelot.com/ Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart Table of Contents Acknowledgments......................................................................................................................................3 PREPARER'S NOTE: ...............................................................................................................................4 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY: ...............................................................................................................4 The Translation..........................................................................................................................................5 Part I: Vv. 1 - Vv. 1840..........................................................................................................................5 Part II: Vv. 1841 - Vv. 3684................................................................................................................25 Part III: Vv. 3685 - Vv. 5594...............................................................................................................45 Part IV: Vv. 5595 - Vv. 7134...............................................................................................................67 Endnotes...................................................................................................................................................84 -

Masculinity and Chivalry: the Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature

MASCULINITY AND CHIVALRY: THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP OF THE SACRED AND SECULAR IN MEDIEVAL ARTHURIAN LITERATURE by KACI MCCOURT DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2018 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Kevin Gustafson, Supervising Professor Jacqueline Fay James Warren i ABSTRACT Masculinity and Chivalry: The Tenuous Relationship of the Sacred and Secular in Medieval Arthurian Literature Kaci McCourt, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2018 Supervising Professors: Kevin Gustafson, Jacqueline Fay, and James Warren Concepts of masculinity and chivalry in the medieval period were socially constructed, within both the sacred and the secular realms. The different meanings of these concepts were not always easily compatible, causing tensions within the literature that attempted to portray them. The Arthurian world became a place that these concepts, and the issues that could arise when attempting to act upon them, could be explored. In this dissertation, I explore these concepts specifically through the characters of Lancelot, Galahad, and Gawain. Representative of earthly chivalry and heavenly chivalry, respectively, Lancelot and Galahad are juxtaposed in the ways in which they perform masculinity and chivalry within the Arthurian world. Chrétien introduces Lancelot to the Arthurian narrative, creating the illicit relationship between him and Guinevere which tests both his masculinity and chivalry. The Lancelot- Grail Cycle takes Lancelot’s story and expands upon it, securely situating Lancelot as the best secular knight. This Cycle also introduces Galahad as the best sacred knight, acting as redeemer for his father. Gawain, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, exemplifies both the earthly and heavenly aspects of chivalry, showing the fraught relationship between the two, resulting in the emasculating of Gawain.