The Plan to Bring the Iconic Passenger Pigeon Back from Extinction | Wired Science | Wired.Com 4/17/13 11:48 AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

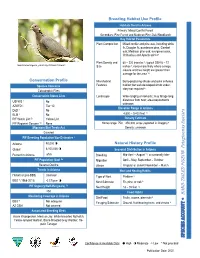

Band-Tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas Fasciata)

Band-tailed Pigeon (Patagioenas fasciata) NMPIF level: Species Conservation Concern, Level 2 (SC2) NMPIF assessment score: 15 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: Watch List New Mexico BCRs: 16, 34, 35 Primary breeding habitat(s): Ponderosa Pine Forest, Mixed Conifer Forest Other habitats used: Spruce-Fir Forest, Madrean Pine-Oak Woodland Summary of Concern Band-tailed Pigeon is a summer resident of montane forests in New Mexico. Both locally and across its wide geographic range the species has shown sharp population declines since the 1960s. Prior to that time, extensive commercial hunting may have significantly reduced the population from historic levels. It is not known if current declines are the result of continuing hunting pressure, habitat changes, or other factors. Associated Species Northern Goshawk, Long-eared Owl, Lewis's Woodpecker (SC1), Acorn Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Olive-sided Flycatcher (BC2), Greater Pewee (BC2), Steller's Jay, Red-faced Warbler (SC1). Distribution A Pacific coast population of Band-tailed Pigeon breeds from central California north to Canada and Alaska, extending south to Baja California in the winter. In the interior, a migratory population breeds in upland areas of southern Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico. The species occurs year-round throughout the highlands of central Mexico, south to Central and South America. In New Mexico, Band-tailed Pigeon breeds in forest habitat throughout the state, west of the plains. It is perhaps most common in the southwest (Parmeter et al. 2002). Ecology and Habitat Requirements In the Southwest, Band-tailed Pigeons inhabit montane forests dominated by pines and oaks, sometimes extending upward in elevation to timberline. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Pigeon, Band-Tailed

Pigeons and Doves — Family Columbidae 269 Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas fasciata California’s only native large pigeon can be seen year round in San Diego’s mountains, sometimes in large flocks, sometimes as only scattered individu- als. Elderberries and acorns are its staple foods, so the Band-tailed Pigeon frequents woodland with abundant oaks. Though it inhabits all the mountains where the black and canyon live oaks are common, its distribution is oddly patchy in foothill woodland dominated by the coast live oak. Both migratory and nomadic, the Band-tailed Pigeon may be common in some areas in some years and absent in others; it shows up occasionally in all regions of the county as Photo by Anthony Mercieca a vagrant. Breeding distribution: As its name in Spanish suggests, ries in dry scrub. Eleanor Beemer noted this movement Palomar Mountain is the center of Band-tailed Pigeon at Pauma Valley in the 1930s, and it continues today. abundance in San Diego County (paloma = pigeon or Some of our larger summer counts, including the largest, dove). The pigeons move up and down the mountain, were in elderberries around the base of Palomar: 35 near descending to the base in summer to feed on elderber- Rincon (F13) 7 July 2000 (M. B. Mosher); 110 in Dameron Valley (C16) 23 June 2001 (K. L. Weaver). Most of the birds nest in the forested area high on the mountain, but some nest around the base, as shown by a fledgling in Pauma Valley (E12) 19 May 2001 (E. C. Hall) and an occupied nest near the West Fork Conservation Camp (E17) 12 May 2001 (J. -

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA CHORDATA 16SCCZO3 Dr. R. JENNI & Dr. R. DHANAPAL DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY M. R. GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE MANNARGUDI CONTENTS CHORDATA COURSE CODE: 16SCCZO3 Block and Unit title Block I (Primitive chordates) 1 Origin of chordates: Introduction and charterers of chordates. Classification of chordates up to order level. 2 Hemichordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Balanoglossus and its affinities. 3 Urochordata: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Herdmania and its affinities. 4 Cephalochordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Branchiostoma (Amphioxus) and its affinities. 5 Cyclostomata (Agnatha) General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Petromyzon and its affinities. Block II (Lower chordates) 6 Fishes: General characters and classification up to order level. Types of scales and fins of fishes, Scoliodon as type study, migration and parental care in fishes. 7 Amphibians: General characters and classification up to order level, Rana tigrina as type study, parental care, neoteny and paedogenesis. 8 Reptilia: General characters and classification up to order level, extinct reptiles. Uromastix as type study. Identification of poisonous and non-poisonous snakes and biting mechanism of snakes. 9 Aves: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Columba (Pigeon) and Characters of Archaeopteryx. Flight adaptations & bird migration. 10 Mammalia: General characters and classification up -

Dynamics of a Problematic Vulture Roost in Southwest Florida and Responses of Vultures to Roost-Dispersal Management Efforts

DYNAMICS OF A PROBLEMATIC VULTURE ROOST IN SOUTHWEST FLORIDA AND RESPONSES OF VULTURES TO ROOST-DISPERSAL MANAGEMENT EFFORTS A thesis Presented to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Florida Gulf Coast University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Science By Betsy A. Evans 2013 APPROVAL SHEET The thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science __________________________________ Betsy A. Evans Approved: December 2013 __________________________________ Jerome A. Jackson, Ph.D. Committee Chair / Advisor __________________________________ Edwin M. Everham III, Ph.D. Committee Member __________________________________ Charles W. Gunnels IV, Ph.D. Committee Member The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost I thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Jerry Jackson, whose support, assistance, and interest throughout the whole process was vital in the preparation and completion of this project. I am grateful to my committee members, Dr. Billy Gunnels and Dr. Win Everham, who provided statistical guidance and vital assistance in the interpretation and editing of the project. I am appreciative to the Department of Marine and Ecological Sciences and the Department of Biological Sciences at Florida Gulf Coast University for their support and encouragement during the completion of my degree. Additionally, I thank the Guadalupe Center of Immokalee for allowing me to conduct research on their property and providing valuable information during the project. A special thank you to the Ding Darling Wildlife Society for their generosity in providing supplemental funding for the project. -

Biological and Environmental Factors Related to Communal Roosting Behavior of Breeding Bank Swallow (Riparia Riparia)

VOLUME 14, ISSUE 2, ARTICLE 21 Saldanha, S., P. D. Taylor, T. L. Imlay, and M. L. Leonard. 2019. Biological and environmental factors related to communal roosting behavior of breeding Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia). Avian Conservation and Ecology 14(2):21. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01490-140221 Copyright © 2019 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Biological and environmental factors related to communal roosting behavior of breeding Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) Sarah Saldanha 1, Philip D. Taylor 2, Tara L. Imlay 1 and Marty L. Leonard 1 1Biology Department, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 2Biology Department, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada ABSTRACT. Although communal roosting during the wintering and migratory periods is well documented, few studies have recorded this behavior during the breeding season. We used automated radio telemetry to examine communal roosting behavior in breeding Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) and its relationship with biological and environmental factors. Specifically, we used (generalized) linear mixed models to determine whether the probability of roosting communally and the timing of departure from and arrival at the colony (a measure of time away from the nest) was related to adult sex, nestling age, brood size, nest success, weather, light conditions, communal roosting location, and date. We found that Bank Swallow individuals roosted communally on 70 ± 25% of the nights, suggesting that this behavior is common. The rate of roosting communally was higher in males than in females with active nests, increased with older nestlings in active nests, and decreased more rapidly with nestling age in smaller broods. -

Ecological Determinants of Pathogen Transmission in Communally Roosting Species

Theoretical Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s12080-019-0423-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Ecological determinants of pathogen transmission in communally roosting species Andrew J. Laughlin1 & Richard J. Hall2,3,4 & Caz M. Taylor5 Received: 16 July 2018 /Accepted: 6 March 2019 # Springer Nature B.V. 2019 Abstract Many animals derive benefits from roosting communally but may also face increased risk of infectious disease transmission. In spite of recent high-profile disease outbreaks in roosting animals of conservation and public health concern, we currently lack general theory for how attributes of roosting animals and their pathogens influence pathogen spread among roosts and overall population impacts on roosting species. Here we develop a model to explore how roost size and host site fidelity influence the time for a pathogen to escape from its initial roost, overall infection prevalence, and host population size, for pathogens with density- or frequency-dependent transmission and varying virulence. We find that pathogens spread rapidly to all roosts when animals are distributed among a small number of large roosts, and that roost size more strongly influences spread rate for density- dependent than frequency-dependent transmitted pathogens. However, roosting animals that exhibit high site fidelity and dis- tribute among a large number of small roosts are buffered from population-level impacts of pathogens of both transmission modes. We discuss our results in the context of anthropogenic change that is altering aspects of roosting behavior relevant to emerging pathogen spread. Keywords Animal aggregations . Communal roost . Pathogen transmission . Roost size . Site fidelity Introduction Hamilton 1982; Thompson 1989), fish (Clough and Ladle, 1997), birds (Eiserer 1984; Beauchamp 1999), and inverte- Animal aggregations occur in a wide variety of taxa, at vary- brates (Mallet 1986;GretherandSwitzer2000). -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Band-Tailed Pigeon, Photo by ©Robert Shantz Size Inches 8; Nests More Likely Where Canopy Closure and Tree Height Are Greater Than Average for the Area 10

Breeding Habitat Use Profile Habitats Used in Arizona Primary: Mixed Conifer Forest Secondary: Pine Forest and Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands Key Habitat Parameters Plant Composition Mixed conifer and pine-oak, including white fir, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, Gambel oak; Madrean pine-oak: evergreen oaks, Chihuahua and Apache pines8 Plant Density and 60 – 200 trees/ac 9; typical DBH 6 – 12 Band-tailed Pigeon, photo by ©Robert Shantz Size inches 8; nests more likely where canopy closure and tree height are greater than average for the area 10 Conservation Profile Microhabitat Berry-producing shrubs and oaks enhance Species Concerns Features habitat; but well-developed shrub under- story not required 8 Catastrophic Fires Conservation Status Lists Landscape Wide-ranging or nomadic; may forage long distances from nest; area requirements USFWS 1 No unknown AZGFD 2 Tier 1C Elevation Range in Arizona 3 DoD No 11 BLM 4 No 4,800 – 9,400 feet PIF Watch List 5b Yellow List Density Estimate PIF Regional Concern 5a None Home range: 750 – 450,000 acres (reported in Oregon) 8 Migratory Bird Treaty Act Density: unknown Covered PIF Breeding Population Size Estimates 6 Arizona 40,000 ◑ Natural History Profile Global 6,100,000 ◑ Seasonal Distribution in Arizona Percent in Arizona .65% Breeding Mid-April – August 11; occasionally later PIF Population Goal 5b Migration April – May; September – October Reverse Decline Winter Irregular or absent November – March Trends in Arizona Nest and Nesting Habits Historical (pre-BBS) Unknown 8 Type of Nest Platform 7 BBS -

Beyond the Information Centre Hypothesis: Communal Roosting for Information on Food, Predators, Travel Companions and Mates?

Oikos 119: 277Á285, 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17892.x, # 2009 The Authors. Journal compilation # 2009 Oikos Subject Editor: Kenneth Schmidt. Accepted 1 September 2009 Beyond the information centre hypothesis: communal roosting for information on food, predators, travel companions and mates? Allert I. Bijleveld, Martijn Egas, Jan A. van Gils and Theunis Piersma A. I. Bijleveld ([email protected]), J. A. van Gils and T. Piersma, Dept of Marine Ecology, Royal Netherlands Inst. for Sea Research (NIOZ), PO Box 59, NLÁ1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, the Netherlands. TP also at: Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Studies, Univ. of Groningen, PO Box 14, NLÁ9750 AA Haren, the Netherlands. Á M. Egas, Inst. for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, Univ. of Amsterdam, PO Box 94248, NLÁ1090 GE Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Communal roosting Á the grouping of more than two individuals resting together Á is common among animals, notably birds. The main functions of this complicated social behaviour are thought to be reduced costs of predation and thermoregulation, and increased foraging efficiency. One specific hypothesis is the information centre hypothesis (ICH) which states that roosts act as information centres where individuals actively advertise and share foraging information such as the location of patchily distributed foods. Empirical studies in corvids have demonstrated behaviours consistent with the predictions of the ICH, but some of the assumptions in its original formulation have made its wide acceptance problematic. Here we propose to generalise the ICH in two ways: (1) dropping the assumption that information transfer must be active, and (2) adding the possibilities of information exchange on, for example, predation risk, travel companions and potential mates. -

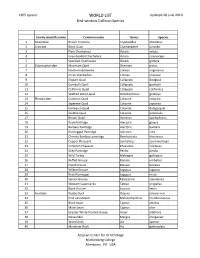

WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-Window Collision Species

1305 species WORLD LIST Updated 28 June 2019 Bird-window Collision Species Family scientific name Common name Genus Species 1 Tinamidae Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 2 Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 3 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 4 Grey-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 5 Speckled Chachalaca Ortalis guttata 6 Odontophoridae Mountain Quail Oreortyx pictus 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 8 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus 9 Elegant Quail Callipepla douglasii 10 Gambel's Quail Callipepla gambelii 11 California Quail Callipepla californica 12 Spotted Wood-quail Odontophorus guttatus 13 Phasianidae Common Quail Coturnix coturnix 14 Japanese Quail Coturnix japonica 15 Harlequin Quail Coturnix delegorguei 16 Stubble Quail Coturnix pectoralis 17 Brown Quail Synoicus ypsilophorus 18 Rock Partridge Alectoris graeca 19 Barbary Partridge Alectoris barbara 20 Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa 21 Chinese Bamboo-partridge Bambusicola thoracicus 22 Copper Pheasant Syrmaticus soemmerringii 23 Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus 24 Grey Partridge Perdix perdix 25 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 26 Ruffed Grouse Bonasa umbellus 27 Hazel Grouse Bonasa bonasia 28 Willow Grouse Lagopus lagopus 29 Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta 30 Spruce Grouse Falcipennis canadensis 31 Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus 32 Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix 33 Anatidae Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 34 Pink-eared Duck Malacorhynchus membranaceus 35 Black Swan Cygnus atratus 36 Mute Swan Cygnus olor 37 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 38