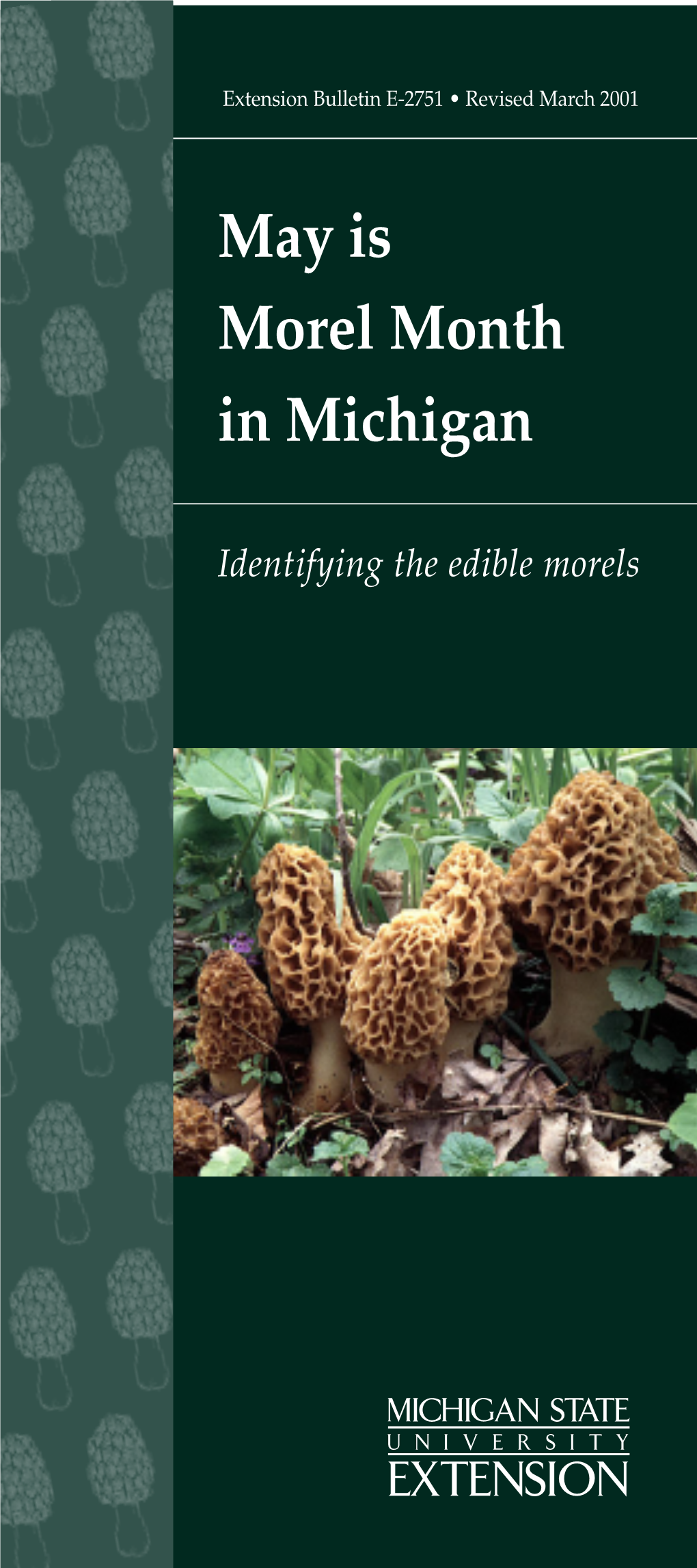

May Is Morel Month in Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMMON Edible Mushrooms

Plate 1. A. Coprinus micaceus (Mica, or Inky, Cap). B. Coprinus comatus (Shaggymane). C. Agaricus campestris (Field Mushroom). D. Calvatia calvatia (Carved Puffball). All edible. COMMON Edible Mushrooms by Clyde M. Christensen Professor of Plant Pathology University of Minnesota THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS Minneapolis © Copyright 1943 by the UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA © Copyright renewed 1970 by Clyde M. Christensen All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the writ- ten permission of the publisher. Permission is hereby granted to reviewers to quote brief passages, in a review to be printed in a maga- zine or newspaper. Printed at Lund Press, Minneapolis SIXTH PRINTING 1972 ISBN: 0-8166-0509-2 Table of Contents ABOUT MUSHROOMS 3 How and Where They Grow, 6. Mushrooms Edible and Poi- sonous, 9. How to Identify Them, 12. Gathering Them, 14. THE FOOLPROOF FOUR 18 Morels, or Sponge Mushrooms, 18. Puff balls, 19. Sulphur Shelf Mushrooms, or Sulphur Polypores, 21. Shaggyrnanes, 22. Mushrooms with Gills WHITE SPORE PRINT 27 GENUS Amanita: Amanita phalloides (Death Cap), 28. A. verna, 31. A. muscaria (Fly Agaric), 31. A. russuloides, 33. GENUS Amanitopsis: Amanitopsis vaginata, 35. GENUS Armillaria: Armillaria mellea (Honey, or Shoestring, Fun- gus), 35. GENUS Cantharellus: Cantharellus aurantiacus, 39. C. cibarius, 39. GENUS Clitocybe: Clitocybe illudens (Jack-o'-Lantern), 41. C. laccata, 43. GENUS Collybia: Collybia confluens, 44. C. platyphylla (Broad- gilled Collybia), 44. C. radicata (Rooted Collybia), 46. C. velu- tipes (Velvet-stemmed Collybia), 46. GENUS Lactarius: Lactarius cilicioides, 49. L. deliciosus, 49. L. sub- dulcis, 51. GENUS Hypomyces: Hypomyces lactifluorum, 52. -

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

Isolation, Characterization, and Medicinal Potential of Polysaccharides of Morchella Esculenta

molecules Article Isolation, Characterization, and Medicinal Potential of Polysaccharides of Morchella esculenta Syed Lal Badshah 1,* , Anila Riaz 1, Akhtar Muhammad 1, Gülsen Tel Çayan 2, Fatih Çayan 2, Mehmet Emin Duru 2, Nasir Ahmad 1, Abdul-Hamid Emwas 3 and Mariusz Jaremko 4,* 1 Department of Chemistry, Islamia College University Peshawar, Peshawar 25120, Pakistan; [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (N.A.) 2 Department of Chemistry and Chemical Processing Technologies, Mu˘glaVocational School, Mu˘glaSıtkı Koçman University, 48000 Mu˘gla,Turkey; [email protected] (G.T.Ç.); [email protected] (F.Ç.); [email protected] (M.E.D.) 3 Core Labs, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 4 Division of Biological and Environmental Sciences and Engineering (BESE), King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.B.); [email protected] (M.J.) Abstract: Mushroom polysaccharides are active medicinal compounds that possess immune-modulatory and anticancer properties. Currently, the mushroom polysaccharides krestin, lentinan, and polysac- Citation: Badshah, S.L.; Riaz, A.; charopeptides are used as anticancer drugs. They are an unexplored source of natural products with Muhammad, A.; Tel Çayan, G.; huge potential in both the medicinal and nutraceutical industries. The northern parts of Pakistan have Çayan, F.; Emin Duru, M.; Ahmad, N.; a rich biodiversity of mushrooms that grow during different seasons of the year. Here we selected an Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. Isolation, edible Morchella esculenta (true morels) of the Ascomycota group for polysaccharide isolation and Characterization, and Medicinal characterization. -

United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,572,364 B2 Langan Et Al

USOO9572364B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,572,364 B2 Langan et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Feb. 21, 2017 (54) METHODS FOR THE PRODUCTION AND 6,490,824 B1 12/2002 Intabon et al. USE OF MYCELIAL LIQUID TISSUE 6,558,943 B1 5/2003 Li et al. CULTURE 6,569.475 B2 5/2003 Song 9,068,171 B2 6/2015 Kelly et al. (71) Applicant: Mycotechnology, Inc., Aurora, CO 2002.01371.55 A1 9, 2002 Wasser et al. (US) 2003/0208796 Al 11/2003 Song et al. (72) Inventors: James Patrick Langan, Denver, CO 3988: A. 58: sistset al. (US); Brooks John Kelly, Denver, CO 2004f02.11721 A1 10, 2004 Stamets (US); Huntington Davis, Broomfield, 2005/0180989 A1 8/2005 Matsunaga CO (US); Bhupendra Kumar Soni, 2005/0255126 A1 11/2005 TSubaki et al. Denver, CO (US) 2005/0273875 A1 12, 2005 Elias s 2006/0014267 A1 1/2006 Cleaver et al. (73) Assignee: MYCOTECHNOLOGY, INC., Aurora, 2006/0134294 A1 6/2006 McKee et al. CO (US) 2006/0280753 A1 12, 2006 McNeary (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2007/O160726 A1 T/2007 Fujii patent is extended or adjusted under 35 (Continued) U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS This patent is Subject to a terminal dis claimer. CN 102860541. A 1, 2013 DE 4341316 6, 1995 (21) Appl. No.: 15/144,164 (Continued) (22) Filed: May 2, 2016 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (65) Prior Publication Data Diekman "Sweeteners Facts and Fallacies: Learn the Truth About US 2016/0249660 A1 Sep. -

2. Typification of Gyromitra Fastigiata and Helvella Grandis

Preliminary phylogenetic and morphological studies in the Gyromitra gigas lineage (Pezizales). 2. Typification of Gyromitra fastigiata and Helvella grandis Nicolas VAN VOOREN Abstract: Helvella fastigiata and H. grandis are epitypified with material collected in the original area. Matteo CARBONE Gyromitra grandis is proposed as a new combination and regarded as a priority synonym of G. fastigiata. The status of Gyromitra slonevskii is also discussed. photographs of fresh specimens and original plates illustrate the article. Keywords: ascomycota, phylogeny, taxonomy, four new typifications. Ascomycete.org, 11 (3) : 69–74 Mise en ligne le 08/05/2019 Résumé : Helvella fastigiata et H. grandis sont épitypifiés avec du matériel récolté dans la région d’origine. 10.25664/ART-0261 Gyromitra grandis est proposé comme combinaison nouvelle et regardé comme synonyme prioritaire de G. fastigiata. le statut de Gyromitra slonevskii est également discuté. Des photographies de spécimens frais et des planches originales illustrent cet article. Riassunto: Helvella fastigiata e H. grandis vengono epitipificate con materiale raccolto nelle rispettive zone d’origine. Gyromitra grandis viene proposta come nuova combinazione e ritenuta sinonimo prioritario di G. fastigiata. Viene inoltre discusso lo status di Gyromitra slonevskii. l’articolo viene corredato da foto di esem- plari freschi e delle tavole originali. Introduction paul-de-Varces, alt. 1160 m, 45.07999° n 5.627088° e, in a mixed for- est, 11 May 2004, leg. e. Mazet, pers. herb. n.V. 2004.05.01. During a preliminary morphological and phylogenetic study in the subgenus Discina (Fr.) Harmaja (Carbone et al., 2018), especially Results the group of species close to Gyromitra gigas (Krombh.) Quél., we sequenced collections of G. -

A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus Communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine

© 2021 JETIR March 2021, Volume 8, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) A Broad Spectrum Activity of Abhal (Juniperus communis) with Special Reference to Unani System of Medicine. A Review * Dr. Aafiya Nargis 1, Dr. Ansari Bilquees Mohammad Yunus 2, Dr. Sharique Zohaib 3, Dr. Qutbuddin Shaikh 4, Dr. Naeem Ahmed Shaikh 5 *1 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Niswan wa Qabalat, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon 2 Associate professor, Dept. Tashreeh ul Badan, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Mansoora, Malegaon. 3 Associate Professor (HOD) Dept. of Saidla, Mohammadia Tibbia College, Manssoora, Malegaon 4 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Tahaffuzi wa Samaji Tibb, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. 5 Professor (HOD), Dept. of Ain, Uzn, Anf, Halaq wa Asnan, Markaz Unani Medical College and Hospital. Kozhikode. Abstract:- Juniperus communis is a shrub or small evergreen tree, native to Europe, South Asia, and North America, and belongs to family Cupressaceae. It has been widely used as herbal medicine from ancient time. Traditionally the plant is being potentially used as antidiarrhoeal, anti-inflammatory, astringent, and antiseptic and in the treatment of various abdominal disorders. The main chemical constituents, which were reported in J. communis L. are 훼-pinene, 훽-pinene, apigenin, sabinene, 훽-sitosterol, campesterol, limonene, cupressuflavone, and many others Juniperus communis L. (Abhal) is an evergreen aromatic shrub with high therapeutic potential in human diseases. This plant is loaded with nutrition and is rich in aromatic oils and their concentration differ in different parts of the plant (berries, leaves, aerial parts, and root). The fruit berries contain essential oil, invert sugars, resin, catechin , organic acid, terpenic acids, leucoanthocyanidin besides bitter compound (Juniperine), flavonoids, tannins, gums, lignins, wax, etc. -

Phylogeny and Historical Biogeography of True Morels

Fungal Genetics and Biology 48 (2011) 252–265 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fungal Genetics and Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yfgbi Phylogeny and historical biogeography of true morels (Morchella) reveals an early Cretaceous origin and high continental endemism and provincialism in the Holarctic ⇑ Kerry O’Donnell a, , Alejandro P. Rooney a, Gary L. Mills b, Michael Kuo c, Nancy S. Weber d, Stephen A. Rehner e a Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens and Mycology Research Unit, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 1815 North University Street, Peoria, IL 61604, United States b Diversified Natural Products, Scottville, MI 49454, United States c Department of English, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920, United States d Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, United States e Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, MD 20705, United States article info summary Article history: True morels (Morchella, Ascomycota) are arguably the most highly-prized of the estimated 1.5 million Received 15 June 2010 fungi that inhabit our planet. Field guides treat these epicurean macrofungi as belonging to a few species Accepted 21 September 2010 with cosmopolitan distributions, but this hypothesis has not been tested. Prompted by the results of a Available online 1 October 2010 growing number of molecular studies, which have shown many microbes exhibit strong biogeographic structure and cryptic speciation, we constructed a 4-gene dataset for 177 members of the Morchellaceae Keywords: to elucidate their origin, evolutionary diversification and historical biogeography. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Classifications of Fungi

Chapter 24 | Fungi 675 Sexual Reproduction Sexual reproduction introduces genetic variation into a population of fungi. In fungi, sexual reproduction often occurs in response to adverse environmental conditions. During sexual reproduction, two mating types are produced. When both mating types are present in the same mycelium, it is called homothallic, or self-fertile. Heterothallic mycelia require two different, but compatible, mycelia to reproduce sexually. Although there are many variations in fungal sexual reproduction, all include the following three stages (Figure 24.8). First, during plasmogamy (literally, “marriage or union of cytoplasm”), two haploid cells fuse, leading to a dikaryotic stage where two haploid nuclei coexist in a single cell. During karyogamy (“nuclear marriage”), the haploid nuclei fuse to form a diploid zygote nucleus. Finally, meiosis takes place in the gametangia (singular, gametangium) organs, in which gametes of different mating types are generated. At this stage, spores are disseminated into the environment. Review the characteristics of fungi by visiting this interactive site (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ fungi_kingdom) from Wisconsin-online. 24.2 | Classifications of Fungi By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following: • Identify fungi and place them into the five major phyla according to current classification • Describe each phylum in terms of major representative species and patterns of reproduction The kingdom Fungi contains five major phyla that were established according to their mode of sexual reproduction or using molecular data. Polyphyletic, unrelated fungi that reproduce without a sexual cycle, were once placed for convenience in a sixth group, the Deuteromycota, called a “form phylum,” because superficially they appeared to be similar. -

Self-Fertility and Uni-Directional Mating-Type Switching in Ceratocystis Coerulescens, a Filamentous Ascomycete

Curr Genet (1997) 32: 52–59 © Springer-Verlag 1997 ORIGINAL PAPER T. C. Harrington · D. L. McNew Self-fertility and uni-directional mating-type switching in Ceratocystis coerulescens, a filamentous ascomycete Received: 6 July 1996 / 25 March 1997 Abstract Individual perithecia from selfings of most some filamentous ascomycetes. Although a switch in the Ceratocystis species produce both self-fertile and self- expression of mating-type is seen in these fungi, it is not sterile progeny, apparently due to uni-directional mating- clear if a physical movement of mating-type genes is in- type switching. In C. coerulescens, male-only mutants of volved. It is also not clear if the expressed mating-types otherwise hermaphroditic and self-fertile strains were self- of the respective self-fertile and self-sterile progeny are sterile and were used in crossings to demonstrate that this homologs of the mating-type genes in other strictly heter- species has two mating-types. Only MAT-2 strains are othallic species of ascomycetes. capable of selfing, and half of the progeny from a MAT-2 Sclerotinia trifoliorum and Chromocrea spinulosa show selfing are MAT-1. Male-only, MAT-2 mutants are self- a 1:1 segregation of self-fertile and self-sterile progeny in sterile and cross only with MAT-1 strains. Similarly, self- perithecia from selfings or crosses (Mathieson 1952; Uhm fertile strains generally cross with only MAT-1 strains. and Fujii 1983a, b). In tetrad analyses of selfings or crosses, MAT-1 strains only cross with MAT-2 strains and never self. half of the ascospores in an ascus are large and give rise to It is hypothesized that the switch in mating-type during self-fertile colonies, and the other ascospores are small and selfing is associated with a deletion of the MAT-2 gene. -

The 2014 Patrice Benson Memorial NAMA Foray October 9-12, 2014

VOLUME 54: 3 May-June 2014 www.namyco.org he 2014 Patrice Benson Memorial NAMA Foray atonville, Washington TE ctober 9-12, 2014 It’s the momentO you’ve all been waiting for—registration time for the 2014 NAMA Foray! Registration will open Monday, May 12 at 9 a.m. Pacific time. Foray attendees and staff will be limited to 250 people, so be sure to register early to get your preferred choice of lodging and to reserve your spot in a pre-foray workshop. Registration will be handled online through the PSMS registration system at www.psms.org/nama2014. If you are unable to complete registration online and need a printed form, contact Pacita Roberts immediately at (206) 498-0922 or mail to: [email protected]. The foray begins Thursday evening, Oct. 9, with dinner and speakers, and ends on Sunday morning, Oct. 12, after the mushroom collection walk-through. The basic package includes 3 nights and 8 meals. The package in- cluding a pre-foray workshop or the trustees meeting starts 2 days earlier on Tuesday night, Oct. 7, and includes 5 nights and 14 meals. The actual workshops and trustees meeting occur on Wednesday, Oct. 8. Speakers Dr. Steve Trudell will serve as the foray mycologist, and he, along with program chair Milton Tam, have ar- ranged an amazing lineup of presenters for 2014. Although the list is not quite finalized, this stellar cast of faculty has already committed: Alissa Allen, Dr. Denis Benjamin, Dr. Michael Beug, Dr. Tom Bruns, Dr. Cathy Cripps, Dr. Jim Ginns, Dr. -

Forest Fungi in Ireland

FOREST FUNGI IN IRELAND PAUL DOWDING and LOUIS SMITH COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development Arena House Arena Road Sandyford Dublin 18 Ireland Tel: + 353 1 2130725 Fax: + 353 1 2130611 © COFORD 2008 First published in 2008 by COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development, Dublin, Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from COFORD. All photographs and illustrations are the copyright of the authors unless otherwise indicated. ISBN 1 902696 62 X Title: Forest fungi in Ireland. Authors: Paul Dowding and Louis Smith Citation: Dowding, P. and Smith, L. 2008. Forest fungi in Ireland. COFORD, Dublin. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of COFORD. i CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................v Réamhfhocal...........................................................................................................vi Preface ....................................................................................................................vii Réamhrá................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...............................................................................................ix