NEW ISSUES in REFUGEE RESEARCH Forced Migration and the Myanmar Peace Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa- an Townships, September to November 2014

Situation Update February 10, 2015 / KHRG #14-101-S1 Thaton Situation Update: Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa- an townships, September to November 2014 This Situation Update describes events occurring in Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa-an townships, Thaton District during the period between September to November 2014, including armed groups’ activities, forced labour, restrictions on the freedom of movement, development activities and access to education. th • On October 7 2014, Border Guard Force (BGF) Battalion #1014 Company Commander Tin Win from Htee Soo Kaw Village ordered A---, B---, C--- and D--- villagers to work for one day. Ten villagers had to cut wood, bamboo and weave baskets to repair the BGF army camp in C--- village, Hpa-an Township. • In Hpa-an Township, two highways were constructed at the beginning of 2013 and one highway was constructed in 2014. Due to the construction of the road, villagers who lived nearby had their land confiscated and their plants and crops were destroyed. They received no compensation, despite reporting the problem to Hpa-an Township authorities. • In the academic year of 2013-2014 more Burmese government teachers were sent to teach in Karen villages. Villagers are concerned as they are not allowed to teach the Karen language in the schools. Situation Update | Bilin, Thaton, Kyaikto and Hpa-an townships, Thaton District (September to November 2014) The following Situation Update was received by KHRG in December 2014. It was written by a community member in Thaton District who has been trained by KHRG to monitor local human rights conditions. It is presented below translated exactly as originally written, save for minor edits for clarity and security.1 This report was received along with other information from Thaton District, including one incident report.2 This report concerns the situation in the region, the villagers’ feelings, armed groups’ activities, forced labour, development activities, support to villagers and education problems occurring between the beginning of September and November 2014. -

Forbidden Songs of the Pgaz K'nyau

Forbidden Songs of the Pgaz K’Nyau Suwichan Phattanaphraiwan (“Chi”) / Bodhivijjalaya College (Srinakharinwirot University), Tak, Thailand Translated by Benjamin Fairfield in consultation with Dr. Yuphaphann Hoonchamlong / University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawai‘i Peer Reviewer: Amporn Jirattikorn / Chiang Mai University, Thailand Manuscript Editor and General Editor: Richard K. Wolf / Harvard University Editorial Assistant: Kelly Bosworth / Indiana University Bloomington Abstract The “forbidden” songs of the Pkaz K’Nyau (Karen), part of a larger oral tradition (called tha), are on the decline due to lowland Thai moderniZation campaigns, internaliZed Baptist missionary attitudes, and the taboo nature of the music itself. Traditionally only heard at funerals and deeply intertwined with the spiritual world, these 7-syllable, 2-stanza poetic couplets housing vast repositories of oral tradition and knowledge have become increasingly feared, banned, and nearly forgotten among Karen populations in Thailand. With the disappearance of the music comes a loss of cosmology, ecological sustainability, and cultural knowledge and identity. Forbidden Songs is an autoethnographic work by Chi Suwichan Phattanaphraiwan, himself an artist and composer working to revive the music’s place in Karen society, that offers an inside glimpse into the many ways in which Karen tradition is regulated, barred, enforced, reworked, interpreted, and denounced. This informative account, rich in ethnographic data, speaks to the multivalent responses to internal and external factors driving moderniZation in an indigenous and stateless community in northern Thailand. Citation: Phattanaphraiwan, Suwichan (“Chi”). Forbidden Songs of the Pgaz K’Nyau. Translated by Benjamin Fairfield. Ethnomusicology Translations, no. 8. Bloomington, IN: Society for Ethnomusicology, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14434/emt.v0i8.25921 Originally published in Thai as เพลงต้องห้ามของปกาเกอะญอ. -

The Myanmar-Thailand Corridor 6 the Myanmar-Malaysia Corridor 16 the Myanmar-Korea Corridor 22 Migration Corridors Without Labor Attachés 25

Online Appendixes Public Disclosure Authorized Labor Mobility As a Jobs Strategy for Myanmar STRENGTHENING ACTIVE LABOR MARKET POLICIES TO ENHANCE THE BENEFITS OF MOBILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Mauro Testaverde Harry Moroz Public Disclosure Authorized Puja Dutta Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar 1 Appendix 2 Forms used to collect information at Labor Exchange Offices 3 Appendix 3 Registering jobseekers and vacancies at Labor Exchange Offices 5 Appendix 4 The migration process in Myanmar 6 The Myanmar-Thailand corridor 6 The Myanmar-Malaysia corridor 16 The Myanmar-Korea corridor 22 Migration corridors without labor attachés 25 Appendix 5 Obtaining an Overseas Worker Identification Card (OWIC) 29 Appendix 6 Obtaining a passport 30 Cover Photo: Somrerk Witthayanant/ Shutterstock Appendix 1 Labor Exchange Offices in Myanmar State/Region Name State/Region Name Yangon No (1) LEO Tanintharyi Dawei Township Office Yangon No (2/3) LEO Tanintharyi Myeik Township Office Yangon No (3) LEO Tanintharyi Kawthoung Township Office Yangon No (4) LEO Magway Magwe Township Office Yangon No (5) LEO Magway Minbu District Office Yangon No (6/11/12) LEO Magway Pakokku District Office Yangon No (7) LEO Magway Chauk Township Office Yangon No (8/9) LEO Magway Yenangyaung Township Office Yangon No (10) LEO Magway Aunglan Township Office Yangon Mingalardon Township Office Sagaing Sagaing District Office Yangon Shwe Pyi Thar Township Sagaing Monywa District Office Yangon Hlaing Thar Yar Township Sagaing Shwe -

Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine

Urban Development Plan Development Urban The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Construction for Regional Cities The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Urban Development Plan for Regional Cities - Mawlamyine and Pathein Mandalay, - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - - - REPORT FINAL Data Collection Survey on Urban Development Planning for Regional Cities FINAL REPORT <SUMMARY> August 2016 SUMMARY JICA Study Team: Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Nine Steps Corporation International Development Center of Japan Inc. 2016 August JICA 1R JR 16-048 Location業務対象地域 Map Pannandin 凡例Legend / Legend � Nawngmun 州都The Capital / Regional City Capitalof Region/State Puta-O Pansaung Machanbaw � その他都市Other City and / O therTown Town Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Don Hee 道路Road / Road � Shin Bway Yang � 海岸線Coast Line / Coast Line Sumprabum Tanai Lahe タウンシップ境Township Bou nd/ Townshipary Boundary Tsawlaw Hkamti ディストリクト境District Boundary / District Boundary INDIA Htan Par Kway � Kachinhin Chipwi Injangyang 管区境Region/S / Statetate/Regi Boundaryon Boundary Hpakan Pang War Kamaing � 国境International / International Boundary Boundary Lay Shi � Myitkyina Sadung Kan Paik Ti � � Mogaung WaingmawミッチMyitkyina� ーナ Mo Paing Lut � Hopin � Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo � Shwe Pyi Aye � Dawthponeyan � CHINA Myothit � Myo Hla Banmauk � BANGLADESH Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Katha Momauk Lwegel � Pinlebu Monekoe Maw Hteik Mansi � � Muse�Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Cikha Wuntho �Manhlyoe (Manhero) � Namhkan Konkyan Kawlin Khampat Tigyaing � Laukkaing Mawlaik Tonzang Tarmoenye Takaung � Mabein -

SIRP Fourpager

Midwife Aye Aye Nwe greets one of her young patients at the newly constructed Rural Health Centre in Kyay Thar Inn village (Tanintharyi Region). PHOTO: S. MARR, BANYANEER More engaged, better connected In brief: results of the Southeast Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (SIRP), Myanmar I first came to this village”, says Aye Aye Nwe, Following Myanmar’s reform process and ceasefires with local “When “things were so different.” Then 34 years old, the armed groups, the opportunity arose to finally improve conditions midwife first came to Kyay Thar Inn village in 2014. - advancing health, education, infrastructure, basic services. “It was my first post. When I arrived, there was no clinic. The The task was huge, and remains considerable today despite village administrators had built a house for me - but it was not a the progress that has been achieved over recent years. clinic! Back then, villagers had no full coverage of vaccinations and healthcare - neither for prevention nor treatment.” The project The Southeast Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project (SIRP) was The nearest rural health centre was eleven kilometres away - a designed to support this process. Starting in late 2012, a long walk over roads that are muddy in the wet season and dusty consortium of Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), the Swiss in the dry. Unsurprisingly, says Nwe, “the health knowledge of Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the Karen villagers was quite poor. They did not know that immunisations Development Network (KDN)* and Action Aid Myanmar (AAM) are a must. Women did not get antenatal care or assistance of sought to enhance lives and living conditions in 89 remote midwives during delivery.” villages across Myanmar’s southeast. -

Report Administration of Burma

REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933=34 RANGOON SUPDT., GOVT. PRINTING AND STATIONERY, BURMA 1935 LIST OF AGENTS FOR THE SALE~OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN BURMA. AllERICAN BAPTIST llIISSION PRESS, Rangoon. BISWAS & Co., 226 Lewis Street, Rangoon. BRITISH BURMA PRESS BRANCH, Rangoon .. ·BURMA BOO!, CLUB, LTD., Poat Box No. 1068, Rangoon. - NEW LIGHT 01' BURlL\ Pl?ESS, 61 Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. PROPRIETOR, THU DHA!IIA \VADI PRE,S, 16-80 lliaun!l :m,ine Street. Rangoon. RANGOOX TIMES PRESS, Rangoon. THE CITY BOOK CLUB, 98 Phayre Street, Rangoon . l\IESSRS, K. BIN HOON & Soi.:s, Nyaunglebin. MAUNG Lu GALE, Law Book Depot, 42 Ayo-o-gale. Manrlalay. ·CONTINENTAL TR.-\DDiG co.. No. 353 Lower Main Road. ~Ioulmein. lN INDIA. BOOK Co., Ltd., 4/4A College Sq<1are, Calcutta. BUTTERWORTH & Co. Undlal, "Ltd., Calcutta . .s. K. LAHIRI & Co., 56 College Street, Calcutta. ,v. NEWMAN & Co., Calcutta. THACKER, SPI:-K & Co., Calcutta, and Simla. D. B. TARAPOREVALA, Soxs & Co., Bombay. THACKER & Co., LTD., Bombay. CITY BOO!! Co., Post Box No. 283, l\Iadras. H!GGINBOTH.UI:& Co., Madras. ·111R. RA~I NARAIN LAL, Proprietor, National1Press, Katra.:Allahabad. "MESSRS. SAllPSON WILL!A!II & Co., Cawnpore, United Provinces, IN }j:URUPE .-I.ND AMERICA, -·xhc publications are obtainable either ~direct from THE HIGH COMMISS!Oli:ER FOR INDIA, Public Department, India House Aldwych, London, \V.C. 2, or through any bookseller. TABLE OF CONTENTS. :REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933-34. Part 1.-General Summary. Part 11.-Departmental Chapters. CHAPTER !.-PHYSICAL AND POLITICAT. GEOGRAPHY. "PHYSICAL-- POLITICAL-co11clcl. -

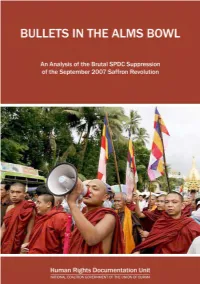

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

Refugee Camps on the Thailand-Myanmar Border: Potential Places for Expanding Connections Among Karen Baptists Boonsong Thansrithong and Kwanchewan Buadaeng*

ASR: CMU Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (2017) Vol. 4 No.2 89 Refugee Camps on the Thailand-Myanmar Border: Potential Places for Expanding Connections among Karen Baptists Boonsong Thansrithong and Kwanchewan Buadaeng* Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] https://doi.org/10.12982/CMUJASR.2017.0006 ABSTRACT Since the 1980s, the Burmese army has increasingly seized the Karen National Union (KNU)’s camps and strongholds along the Thailand-Myanmar borderland. Hundreds of thousands of Karen people affected by the war have fled to the Thai side of the border. Since then, ten refugee camps have existed along the border, from Mae Hong Son province in the North to Ratchaburi province in the South. This paper focuses on the operation of the Kawthoolei Karen Baptist Bible School and College (KKBBSC) in the Bae Klaw camp, which is the largest with almost 40,000 residents in 2016. Since 1990, the KKBBSC has produced around 1,000 Bachelor of Theology graduates, thereby increasing the strength of the Karen Baptist church. This paper argues that the refugee camps on the Thailand-Myanmar border are not marginally isolated, but are potential nodes of connection with other places and organiza- tions. Two factors contribute to the potentialities of the camps. First, the camp is an exceptional zone, ruled not by a single government but a liminal contested space of many actors. The second is the camp’s high level of technological development which facilitates transportation and communication for the Karen Baptists. -

Karen Refugees in Thailand

Karen refugees in Thailand (A young refugee in the village of Moh Ger Thai, Tak province, Thailand) Student: Alessio Fratticcioli Course: Theories of International Migration Professor: Dr. Supang Chantavanich MA Southeast Asian Studies Chulalongkorn University 1 INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION I/ Background II/ Objectives III/ Scope, Limitation and Positive Aspects IV/ Structure 2. WHO IS A REFUGEE? 3. REFUGEES: THE KAREN CASE I/ RTG’s policies towards Myanmar displaced persons II/ Current situation in Mae Sot and Mae La camp 4. CONCLUSION 2 1. INTRODUCTION I/ Background of the Study 1 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar shares a long 2,400km porous border with Thailand, a line steadily crossed by an ever growing flow of people. According to the latest figures, 146,563 people2 are registered in the 10 border camps in the Thai side, the large majority being of Karen ethnicity3. The two genders are roughly equally represented. Another estimated 200,000 refugees live outside the sites and about 2 million Burmese reside in Thailand4, most of them illegally. The flow of Burmese people crossing the border has been going on for decades – at least until 19495 - and it appears to be growing in number6. Since long ago, Thailand had to accept the protracted refugee burden. Nevertheless, the Kingdom is clearly unenthusiastic in being an indefinite host and is actively exploring different solutions; among them repatriation and resettlement in third countries. Moreover, in the last years the growing economic relations between Bangkok and Naypyidaw7 had as a result a change in the approach of the Thai Royal Government (TRG) to the Myanmar refugees’ issue: policies got stricter, and multi-ranged solutions have been explored. -

Pdf | 17.04 Mb

Thailand-Myanmar 7th Edition CROSS BORDER BULLETIN February 2016 Livelihoods Support in Kayah State Building Bridges in Mon State Singing for Birth Certificates in Mae La Refugee Camp Aspirations of Youth Club in Ban Mai Nai Soi Refugee Camp Moving on! UNHCR Protection Officer, Mae Sariang, Thailand EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW Reverend Robert, Chairperson of the Karen Refugee Committee © UNHCR/K.Park © © UNHCR Community-Based Livelihoods Support: IDP and Refugee Return in Kayah State Daw Boe Mae is a housewife with four children living in Daw Boe Mae works really hard. Having received a Daw Ngay Khu village in Demoso Township of Kayah State, 150,000 MMK grant from DRC DDG’s livelihoods team, she Myanmar. Whilst three of her children are schooling, one was able to set up a small grocery shop at the family home infant still needs caring for, so before this project, she was and now generates a regular income of between 5,000– not able to work to support her husband and supplement 10,000 MMK every day. With this, she is not only able to the family income. They were entirely dependent on the feed her family, but is investing more in the shop. She is husband’s meagre earnings through planting sesame and now also trying to diversify into pig breeding and has peanut. already bought one sow. However, this was insufficient for the family’s basic daily The income that Daw Boe Mae now earns is proving very needs and Daw Boe Mae had no choice but to ask for food helpful not only for the family’s daily food consumption, for the next day from local sellers. -

A Corpus-Based Study of the Function and Structure of Numeral Classifier Constructions in S’Gaw Karen

A CORPUS-BASED STUDY OF THE FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE OF NUMERAL CLASSIFIER CONSTRUCTIONS IN S’GAW KAREN by Collin Olson A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Middle Tennessee State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Murfreesboro, TN May 2014 Thesis Committee: Dr. Aleka Blackwell Dr. Tom Strawman liypaxjoI ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have completed this project without the patience and guidance of Dr. Aleka Blackwell. It was in Dr. Blackwell’s classes that I first decided to pursue a career in linguistics, and I was fortunate to serve as her research assistant while completing my MA. I am very thankful to have had an advisor who has stuck with me through what became a complicated and prolonged project. I give many thanks to Dr. Tom Strawman, who has been a good friend and mentor for the past fourteen years. The S’gaw Karen community in Smyrna, Tennessee has been instrumental in gathering the data for this project and helping me to learn about the S’gaw Karen language, culture, and history. Working with the S’gaw Karen community as an ESL teacher has been a rewarding experience both professionally and personally, and I hope that the S’gaw Karen people thrive in their new home. Most importantly, I give thanks for the support from my family. I am especially grateful for the patience and encouragement of my wife, Selena, and our two daughters. iii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the numeral classifier system in S’gaw Karen, a language in the Tibeto-Burman subfamily. -

Towards Universal Education in Myanmar's Ethnic Areas

Strength in Diversity: Towards Universal Education in Myanmar’s Ethnic Areas Kim Jolliffe and Emily Speers Mears October 2016 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all of the ethnic basic education providers that have worked for many years to serve their communities. In particular, the Karen Education Department, Karen Teacher Working Group, Mon National Education Committee and Department, and the Rural Development Foundation of Shan State and associates, all gave their time, resources, advice and consideration to make this report possible. Additionally, World Education, Myanmar Education Consortium, UNICEF, Child’s Dream, Save the Children, and all at the Education Thematic Working Group have been instrumental in the development of this work, providing information on their programs, making introductions, discussing their own strengths and challenges, providing feedback on initial findings, and helping to paint a deeper picture of what international support to ethnic basic education looks like. In particular, big thank yous to Dr. Win Aung, Aye Aye Tun, Dr. Thein Lwin (formerly worked for the Ministry of Education), Craig Nightingale, Amanda Seel, Catherine Daly, and Andrea Costa for reviewing early drafts of the paper and providing invaluable feedback, which has helped the report grow and develop considerably. About the Authors Having worked in Southeast Asia for over eight years, Kim Jolliffe is an independent researcher, writer, analyst and trainer, specializing in security, aid policy, and ethnic politics in Myanmar/Burma. He is the lead researcher on the Social Services in Contested Areas (SSCA) research project. Emily Speers Mears is a researcher and policy adviser specializing in education and conflict in fragile states.