Excavation and Survey 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

The London Gazette, August 30, 1898

5216 THE LONDON GAZETTE, AUGUST 30, 1898. DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 AND 1896. RETURN of OUTBREAKS of the undermentioned DISEASES for the Week ended August 27th, 1898, distinguishing Counties fincluding Boroughs*). ANTHRAX. GLANDERS (INCLUDING FARCY). County. Outbreaks Animals Animals reported. Attacked. which Animals remainec reported Oui^ Diseased during ENGLAND. No. No. County. breaks at the the reported. end of Week Northampton 2 6 the pre- as At- Notts 1 1 vious tacked. Somerset 1 1 week. Wilts 1 1 WALES. ENGLAND. No. No. No. 1 Carmarthen 1 1 London 0 15 Middlesex 1 • *• 1 Norfolk 1 SCOTLAND. Kirkcudbright 1 1 SCOTLAND. Wigtown . ... 1 1 1 1 TOTAL 8 " 12 TOTAL 10 3 17 * For convenience Berwick-upon-Tweed is considered to be in Northumberland, Dudley is con- sidered to be in Worcestershire, Stockport is considered to be in Cheshire, and the city of London ia considered to be in the county of London. ORDERS AS TO MUZZLING DOGS, Southampton. Boroughs of Portsmouth, and THE Board of Agriculture have by Order pre- Winchester (15 October, 1897). scribed, as from the dates mentioned, the Kent.—(1.) The petty sessional divisions of Muzzling of Dogs in the districts and parts of Rochester, Bearstead, Mailing, Cranbrook, Tun- districts of Local Authorities, as follows :—• bridge Wells, Tunbridge, Sevenoaks, Bromley, Berkshire.—The petty sessional divisions of and Dartford (except such portions of the petty Reading, Wokinghana, Maidenhead, and sessional divisions of Bromley and Dartford as Windsor, and the municipal borough of are subject to the provisions of the City and Maidenhead, m the county of Berks. -

MORTIMER WEST END PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting Of

MORTIMER WEST END PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting of the Council Date: Wednesday 8th June 2016 Time: 7.35pm Place: Mortimer West End Village Hall Present: Cllr Robertson (Chair) Cllr Thurlow (Vice Chair) Cllr Brown In Attendance: Christine McGarvie (Clerk) 0 members of the public Aimee Scott- Molloy – PCSO Cllr Marilyn Tucker (Borough) Cllr Keith Chapman (County) Apologies: Cllr Gardiner (Borough) Action 1 Apologies for Absence None. 2 Declarations of Interest None. 3 Minutes of the Last Parish Council Meeting and the AGM 3.1 It was unanimously agreed that the minutes of the meeting held 27th April 2016 were a true and accurate record. It was unanimously agreed that the minutes of the AGM meeting held 17th May 2016 were a true and accurate record. The minutes were signed by the Chairman. Minutes of the APM to be signed at the next meeting. 3.2 Matters arising None 4 Open Forum 4.1 The Chairman invited questions and comments from those present. Aimee Scott-Molloy, the Police Community Support Officer gave a report on policing in the parish. The main problem they are dealing with is motorbikes Clerk on the Englefield estate which is cross border ie. West Berkshire and Hampshire. There has recently been a fire in the forest which is suspected to be arson. In May there were 2 incidents of motorbikes on the estate and there have been upwards of 15 reports in other months. There were 2 burglaries in May, one was a non-dwelling shed on Park Lane and second was a burglary on Simms Lane where a significant amount of jewellery was stolen. -

Division Arrangements for Hartley Wintney & Yateley West

Mortimer West End Silchester Stratfield Saye Bramshill Heckfield Eversley Yateley Stratfield Turgis Calleva Pamber Bramley Mattingley Hartley Wespall Hartley Wintney & Yateley West Yateley East & Blackwater Blackwater and Hawley Hartley Wintney Farnborough North Sherborne St. John Sherfield on Loddon Rotherwick Farnborough West Elvetham Heath Chineham Fleet Hook Fleet Town Basingstoke North Winchfield Farnborough South Newnham Old Basing and Lychpit Loddon Church Crookham Basingstoke Central Odiham & Hook Dogmersfield Crookham Village Mapledurwell and Up Nately Church Crookham & Ewshot Greywell Aldershot North Basingstoke South East Odiham Ewshot Winslade Aldershot South Candovers, Oakley & Overton Crondall Cliddesden South Warnborough Tunworth Upton Grey Farleigh Wallop Long Sutton County Division Parishes 0 0.75 1.5 3 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Hartley Wintney & Yateley West © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Emsworth & St Faiths North West Havant Hayling Island County Division Parishes 0 0.4 0.8 1.6 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Hayling Island © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Durley Bishops Waltham West End & Horton Heath West End Botley & Hedge End North Hedge End Curdridge Hedge End & West End South Meon Valley Botley Bursledon Hound Hamble Fareham Sarisbury Whiteley County Division Parishes 0 0.275 0.55 1.1 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown -

Polling Stations Ancells Farm Community Centre, 1 Falkners

Polling Stations Ancells Farm Community Centre, 1 Falkners Close, Ancells Farm, GU51 2XF Annexe Preston Candover Village Hall, Preston Candover, Basingstoke, RG25 2EP Bramley C E Primary School, Bramley Lane, Bramley, RG26 5AH Bramley Village Hall, The Street, Bramley, RG26 5BP Catherine of Aragon (Private House), Pilcot Hill, RG27 8SX Church Crookham Baptist Church, 64 Basingbourne Road, Fleet, GU52 6TH Church Crookham Community Centre, Boyce Road, (Off Jubilee Drive and Gurung Way), GU52 8AQ Civic Offices - Side Entrance (A & B), Adjacent to the Citizens Advice Bureau, Hart District Council, GU51 4AE Civic Offices - Main Entrance (C & D), Hart District Council, Harlington Way, GU51 4AE Cliddesden Millennium Village Hall, Cliddesden, Basingstoke, RG25 2JQ Crondall Church Rooms, Croft Lane, GU10 5QF Crookham Street Social Club, The Street, Crookham Village, GU51 5SJ Darby Green & Frogmore Social Hall, Frogmore Road, Blackwater, GU17 0NP Ellisfield Memorial Hall, Church Lane, Ellisfield, RG25 2QR Eversley Village Hall, Reading Road, Eversley, RG27 0LX Ewshot Village Hall, Tadpole Lane, Ewshot, GU10 5BX Farleigh Wallop Clubroom, The Avenue, Farleigh Wallop, RG25 2HU Greywell Village Hall, The Street, Greywell, RG29 1BZ Hart Leisure Centre, Emerald Avenue, Off Hitches Lane, GU51 5EE Hawley Memorial Hall, Fernhill Road, Hawley Green, GU17 9BW Heckfield Memorial Hall, Church Lane, Heckfield, RG27 0LG Herriard Royal British Legion Hall, Herriard, RG25 2PG Holy Trinity Church Hall (Cana Room), Bowenhurst Road, Off Aldershot Road, GU52 8JU Long -

Appendix 11 Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Parish

Appendix 11 Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Parish Requirements 2014/15 Council Council Tax Element Tax for Parish Purposes Parish/Area Precept Base (*) at Band D (**) £ £ (1) (2) (3) (4) Ashford Hill with Headley 19,000.00 599.3 31.70 Ashmansworth 3,000.00 106.4 28.20 Baughurst 38,500.00 1,015.3 37.92 Bramley 65,000.00 1,590.8 40.86 Burghclere 9,600.00 554.0 17.33 Candovers 3,000.00 101.2 29.64 Chineham 36,800.00 3,072.7 11.98 Cliddesden 5,850.00 231.1 25.31 Dummer 6,500.00 219.5 29.61 East Woodhay 25,165.00 1,301.7 19.33 Ecchinswell, Sydmonton and Bishops Green 11,299.00 421.4 26.81 Ellisfield 5,521.00 145.2 38.02 Hannington 3,312.00 184.6 17.94 Highclere 13,466.00 741.7 18.16 Hurstbourne Priors 7,000.00 177.9 39.35 Kingsclere 40,735.00 1,284.2 31.72 Laverstoke and Freefolk 10,000.00 166.7 59.99 Mapledurwell and Up Nately 6,562.00 276.6 23.72 Monk Sherborne 9,450.00 179.8 52.56 Mortimer West End 7,400.00 180.2 41.07 Newnham 6,122.00 237.1 25.82 Newtown 3,500.00 131.3 26.66 North Waltham 10,100.00 384.2 26.29 Oakley and Deane 76,695.00 2,240.9 34.23 Old Basing and Lychpit 129,574.00 3,079.0 42.08 Overton 66,570.00 1,707.9 38.98 Pamber 25,500.00 1,160.3 21.98 Preston Candover and Nutley 7,000.00 239.2 29.26 Rooksdown 19,600.00 1,358.8 14.42 Sherborne St John 22,700.00 521.5 43.53 Sherfield-on-Loddon 75,000.00 1,514.3 49.53 Silchester 14,821.00 417.7 35.48 St Mary Bourne 19,572.00 578.9 33.81 Stratfield Saye 2,750.00 136.9 20.09 Tadley 186,466.00 4,004.5 46.56 Upton Grey 14,000.00 343.5 40.76 Whitchurch 75,000.00 1,846.4 40.62 Wootton -

Basingstoke Union Workhouse, Census 1911 2 April 1911 (Inmates Only)

Basingstoke Union Workhouse, Census 1911 2 April 1911 (Inmates only) Names written in Enumerator's Book with surname last ... Name and Surname M F Condition Occupation Birthplace Infirmity Andrews, John 82 widower Farm Labourer Ellisfield Andrews, William 40 s nil Basingstoke Appleton, Sarah 81 widow Bramley Arlest, Doris 2 H...Heath, Hants Baker, Edward 54 s Farm Labourer ?.....Hants Baker, Ellen 22 s General Servant Stratfieldsaye Ball, David 49 Farm Labourer Pamber Beech, William 50 s Farm Labourer Mortimer, Hants Beech, Lily 37 widow E...Green, Oxon Beech, Leonard 12 School Mortimer Beech, Eric 11 School Stratfieldsaye Beech, Dorothy 9 School Stratfieldsaye Benham, Albert 3 London Benham, Lucy 29 s General Servant Mortimer West End Benham, Arthur 2 Reading, Berks Bennett, Elizabeth 75 widow Stratfieldsaye Boham, Walter 68 widower Gardener Basingstoke Bond, Thomas 63 widower Railway Porter Eve..... Berks Bowley, Emily 12 School Whitchurch Broadhurst, Thomas 80 s Farm Labourer Silchester Brown, James 81 s Sweep Jersey Burgess, Charles 66 widower Gardener Overton Bye, William 54 Farm Labourer Wootton St Lawrence Carter, Thomas 85 widower Farm Labourer Weston Corbett Carter, Alfred 64 s Farm Labourer South Warnborough, Hants Carter, Mabel 9 School Basing Carter, Daniel 5 School Basing Chandler, George 74 widower General Labourer Basingstoke Chandler, Mary 64 widow Tadley Chandler, Rose 27 s Tadley Imbecile from birth Chesterman, Frederick 42 s Pamber Cripple from birth Clarke, Henry 59 s Farm Labourer Gray..... Hants Page 1 Clay, Martha -

Some Suggested Ride and Stride Routes ( Mileages Approximate)

Some Suggested Ride and Stride Routes ( mileages approximate) Andover Area Huntingdon’s Connexion Chapel Burghclere, The Ascension - Silchester Methodist Church Woolton Hill, S Thomas - Return to Silchester, S Mary The Highclere, S Michael & All Angels 22 Miles Virgin Described as the minimum distance, 10 miles maximum church route! 10 miles Newtown, S Mary The Virgin - Appleshaw, S Peter in the Wood A more linear walk, a little long on foot? Burghclere, The Ascension - Fyfield, S Nicholas Traversing woods on cycle may be a Woolton Hill, S Thomas - Thruxton, SS Peter & Paul little tricky, but minor roads can be East Woodhay, S Martin - Kimpton, SS Peter & Paul used Highclere, S Michael & All Angels - Quarlet, S Michael Ecchinswell, S Lawrence - Grately, S Leonard - Pamber Heath, S Luke Headley, S Peter - Amport, S Mary - Tadley, United Reformed Church (Old Ashford Hill, S Paul - Monxton, S Mary Meeting) - Abbots Ann, S Mary - Tadley, Main Road Methodist Church Over 10 miles - Andover West, S Michael & All Angels - Tadley, S Paul - Charlton, S Thomas - Tadley, S Peter - Newtown, S Mary The Virgin - Penton Mewsey, Holy Trinity - Pamber Priory - Burghclere, The Ascension - Weyhill, S Michael & All Angels - Little London, S Stephen - Woolton Hill, S Thomas Return to Appleshaw - Bramley, S James - St Mary Bourne, S Peter (optional return to Pamber Heath) - Crux Easton, S Michael & All Angels 74 miles - Ashmansworth, S James Over 10 miles (connections with Finzi, the composer) - Appleshaw, S Peter in the Wood A good circular ride, but partly -

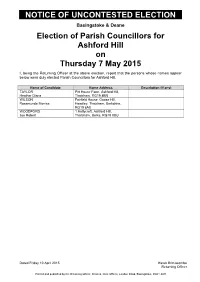

Notice of Uncontested Parish Election(PDF)

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Basingstoke & Deane Election of Parish Councillors for Ashford Hill on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ashford Hill. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) TAYLOR Pitt House Farm, Ashford Hill, Heather Diana Thatcham, RG19 8BN WILSON Fairfield House, Goose Hill, Rosamunde Monica Headley, Thatcham, Berkshire, RG19 8AU WOODFORD 1 Hollycroft, Ashford Hill, Joe Robert Thatcham, Berks, RG19 8BU Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Karen Brimacombe Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Deanes, Civic Offices, London Road, Basingstoke, RG21 4AH NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Basingstoke & Deane Election of Parish Councillors for Candovers on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Candovers. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CURTIS HAYWARD Totford Farm, Northington, Edwina Gay Alresford, Hants, SO24 9TJ MARRIOTT Chilton Down House, Chilton Susan Candover, SO24 9TX MOSELEY Robey`s Farm House, Brown Jonathan Charles Arthur Foster Candover, Alresford, SO24 9TN Commonly known as MOSELEY Jonathan PEISLEY Gumnut Cottage, Brown Diana Candover, Alresford, Hampshire, SO24 9TR WILLMOTT Willowbrook Cottage, Duck Lane, Adam Edward Brown Candover, Hampshire, SO24 9TN Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Karen Brimacombe Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Deanes, Civic Offices, London Road, Basingstoke, RG21 4AH NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Basingstoke & Deane Election of a Parish Councillor for Church Oakley on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the person whose name appears below was duly elected Parish Councillor for Church Oakley. -

Basingstoke and Deane Borough Council Notices of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL Basingstoke & Deane Election of Councillors for Basing & Upton Grey Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Councillors to be elected is three. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) CUBITT Kolkinnon House, Conservative Party Hugo Cubitt (+) William M Cubitt (++) Onnalee Virginia Blaegrove Lane, Up Candidate Nately, Hook, RG27 9PD GODESEN 71 The Street, Old Conservative Party Trixie J Godesen (+) Catherine B Tuck (++) Sven Howard Basing, Basingstoke, Candidate RG24 7BY KENNAN (Address in Liberal Democrat Mary Kennan (+) Catherine S F Bell (++) James Anthony Basingstoke and Deane) LILLEKER (Address in Liberal Democrat Raymond D Ripton (+) Jane E Ripton (++) Richard Mark Basingstoke and Deane) LOWE (Address in Labour Party Gillian Noble (+) David Noble (++) Beth Basingstoke and Deane) MOYNIHAN (Address in Hampshire Adam C T Lippitt (+) Kathleen M Williams Anna Basingstoke and Independents (++) Deane) RUFFELL (Address in Conservative Party John W Guy (+) James R Whitcombe Mark Beresford Basingstoke and Candidate (++) Deane) 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation -

TO LET the OLD SCHOOL HOUSE Mortimer West End, Reading, Berkshire the OLD SCHOOL HOUSE Mortimer West End, Reading, Berkshire

TO LET THE OLD SCHOOL HOUSE Mortimer West End, Reading, Berkshire THE OLD SCHOOL HOUSE Mortimer West End, Reading, Berkshire Reading 8 miles u Basingstoke 7 miles u Newbury 10 miles u M4 ﴾junction 11﴿ 7 miles u M3 ﴾junction 5﴿ 9 miles u Mortimer Station 2.5 miles with services to Basingstoke ﴿and Reading u London Paddington via Reading station 30 minutes u London Waterloo from Basingstoke station 45 minutes. ﴾Distances and times are approximate Accomodation and Amenities Hall u Cloakroom u Sitting Room u Dining Room or play room u Study u Snug u Kitchen/Breakfast Room u Utility Room u Master en‐suite u 4 further Bedrooms 2 further Bathrooms u 1 bed annexe u useful outbuildings u attractive secluded gardens and access to adjoining woodland. Description of Property Once the village school, the house is light and airy, with good living space and room sizes and much character and practicality of layout. Mortimer West End is a low‐key little community offering excellent access to all the key roads and railway stations in the area and is perfectly located for Berkshire's many first‐class schools. On the ground floor, there is a spacious drawing room and also a large dining room ﴾currently children’s games room﴿, a good kitchen with off‐lying snug and also a quiet study. Upstairs, two large bedrooms ﴾one ensuite﴿ are complemented by 3 further bedrooms served by a central landing. The former garage contains a single‐bed maisonette and there is a good shed for tools, toys and firewood. Outside, the gardens are a well tended combination of lawns and shrubs and one fabulous feature is the ability to walk in the surrounding private woods. -

The BRAMLEY Magazine

October 2017 The BRAMLEY Magazine Superfast Broadband Bramley Show Winners Volunteers Wanted! Plus all the regular articles and much more FOR BRAMLEY AND LITTLE LONDON 2 WELCOME What is it about 1967? As you read the magazine you will see that it was a The special year in a lot of people’s lives. In Meet the Neighbours John and Ann Lenton remember their wedding in September 1967 and tell us what has kept them together over the last 50 years. The Lunch Club celebrated another Bramley golden wedding – this time it was Robin and Jo Dolman’s. Congratulations to both couples. Michael Luck was too young to get married in 1967 but he Magazine was into his music and on page 9 he recalls how the pirate radio stations were banned that year, paving the way for the launch of Radio 1. I also know a few for Bramley and people in Bramley and Little London born in 1967 but I will spare their blushes and just remind them that 50 is the new 40. Of course, I am far too young to Little London remember 1967 having been born much later – well two months later anyway…. A lot has changed since 1967. Back then you could buy a loaf of bread for 7p, October 2017 the average house price was £2,530 and a season ticket to see Manchester Chairman of Steering Group: United cost £8.50. Mobile phones and Facebook were unheard of and society Rhydian Vaughan was different too. During the 1967 marathon in Boston an official tried to [email protected] remove Kathy Switzer from the race because at that time women were not allowed to compete in the marathon.