Heterodon Latreille Hognose Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SNAKES of SURINAM, PART XVI: SUBFAMILY XENO- By: A

-THE SNAKES -OF SURINAM, ---PART XVI: SUBFAMILY --XENO- DONTINAE ( GENERA WAGLEROPHIS., XENODON AND XENO PHOLIS). By: A. Abuys, Jukwerderweg 31, 9901 GL Appinge dam, The Netherlands. Contents: The genus WagZerophis - The genus Xeno don - The genus XenophoZis - References. THE GENUS wAGLEROPHIS ROMANO & HOGE, 1972 This genus contains only one species. Prior to 1972 this species was known as Xenodon merremii (Wagler, 1824). This species is found in Surinam. General data for the genus: Head: The head is short and slightly flattened. The strong neck is only marginally narrower than the head. The relatively large eyes have round pupils. Body: Short and stout with smooth scales. The scales have one apical groove. The formation of the dorsal scales is characteristic for this genus. These are arranged so that the upper rows are at an angle to the lower ones (see figure 1) . Tail: Short. Behaviour: Terrestrial and both nocturnal and di urnal. Food: Frogs, toads, lizards and sometimes snakes, insects or small mammals. Habitat: Damp forest floors near swamps or water. Reproduction: Oviparous. Remarks: When threatened or disturbed, the fore part of the body is inflated and the neck is spread in a cobra-like fashion. The head is al· so raised slightly, but not as high and as 181 Fig. 1. Dorsal scale pattern of Waglerophis. From: Peters & Orejas-Miranda, 1970. vertically as a cobra. This is an aggressive snake which will invariably resort to biting if the warning behaviour described above is not heeded. This genus (in common with the genera Xenodon, Heterodon and Lystrophis) has two enlarged teeth attached to the back of the upper jaw. -

The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M

The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M. Cei Instituto de Biología Animal Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Casilla Correo 327 Mendoza, Argentina Reprinted from: Duellman, William E. (ed.). 1979. The South American Herpetofauna: Its origin, evolution, and dispersal. Univ. Kansas Mus. Nat. Hist. MonOgr. 7: 1-485. Copyright © 1979 by The Museum of Natural History, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. 13. The Patagonian Herpetofauna José M. Cei Instituto de Biología Animal Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Casilla Correo 327 Mendoza, Argentina The word Patagonia is derived from the longed erosion. Scattered through the region term “Patagones,” meaning big-legged men, are extensive areas of extrusive basaltic rocks. applied to the tall Tehuelche Indians of The open landscape is dissected by transverse southernmost South America by Ferdinand rivers descending from the snowy Andean Magellan in 1520. Subsequently, this pic cordillera; drainage is poor near the Atlantic turesque name came to be applied to a con coast. Patagonia is subjected to severe sea spicuous continental region and to its biota. sonal drought with about five cold winter Biologically, Patagonia can be defined as months and a cool dry summer, infrequently that region east of the Andes and extending interrupted by irregular rains and floods. southward to the Straits of Magellan and eastward to the Atlantic Ocean. The northern boundary is not so clear cut. Elements of the HISTORY OF THE PATAGONIAN BIOTA Pampean biota penetrate southward along the coast between the Rio Colorado and the Rio In contrast to the present, almost uniform Negro (Fig. 13:1). Also, in the west Pata steppe associations in Rio Negro, Chubut, gonian landscapes and biota enter the vol and Santa Cruz provinces, during Oligocene canic regions of southern Mendoza, almost and Miocene times tropical and subtropical reaching the Rio Atuel Basin. -

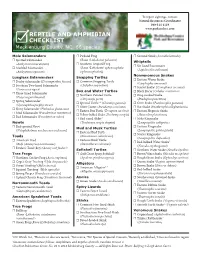

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Caderno De Resumos EHFB 2015

Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes Tatiana Tavares da Silva Rosa Andrea Lopes de Souza (Organizadoras) Anais do Encontro de História e Filosofia da Biologia 2015 São Paulo Instituto de Biociências (IB/USP) 2015 Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes Tatiana Tavares da Silva Rosa Andrea Lopes de Souza (Organizadoras) Anais do Encontro de História e Filosofia da Biologia 2015 Instituto de Biociências Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo 29 a 31 de julho de 2015 Promoção: ABFHiB, Associação Brasileira de Filosofia e His- tória da Biologia Apoio: Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo (IB-USP) Núcleo de Pesquisa em Educação, Divulgação e Epistemologia da Evolução (EDEVO-Darwin) Laboratório de História da Biologia e Ensino (IB-USP) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Genética e Biologia Evolutiva) do IB-USP Programa de Pós-Graduação Interunidades em Ensino de Ciências da USP Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) ENCONTRO DE HISTÓRIA E FILOSOFIA DA BIOLOGIA 2015 São Paulo, 29 a 31 de agosto de 2015 LOCAL: Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo – Edifício Félix Kurt Rawitsher (“Minas”) PROMOÇÃO: Associação Brasileira de Filosofia e História da Biologia (ABFHiB) http://www.abfhib.org COMISSÃO ORGANIZADORA: Maria Elice Brzezinski Prestes (IB-USP) Nelio Bizzo (FE-USP) Maurício de Carvalho Ramos (FFLCH-USP) Hamilton Haddad (IB-USP) COMISSÃO CIENTÍFICA: Aldo M. de Araújo (Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul) Ana Maria de Andrade Caldeira (Universidade Estadual Paulista) Anna Carolina Regner -

Short Communication Non-Venomous Snakebites in the Western Brazilian

Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical Journal of the Brazilian Society of Tropical Medicine Vol.:52:e20190120: 2019 doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0120-2019 Short Communication Non-venomous snakebites in the Western Brazilian Amazon Ageane Mota da Silva[1],[2], Viviane Kici da Graça Mendes[3],[4], Wuelton Marcelo Monteiro[3],[4] and Paulo Sérgio Bernarde[5] [1]. Instituto Federal do Acre, Campus de Cruzeiro do Sul, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil. [2]. Programa de Pós-Graduação Bionorte, Campus Universitário BR 364, Universidade Federal do Acre, Rio Branco, AC, Brasil. [3]. Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brasil. [4]. Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado, Manaus, AM, Brasil. [5]. Laboratório de Herpetologia, Centro Multidisciplinar, Campus Floresta, Universidade Federal do Acre, Cruzeiro do Sul, AC, Brasil. Abstract Introduction: In this study, we examined the clinical manifestations, laboratory evidence, and the circumstances of snakebites caused by non-venomous snakes, which were treated at the Regional Hospital of Juruá in Cruzeiro do Sul. Methods: Data were collected through patient interviews, identification of the species that were taken to the hospital, and the clinical manifestations. Results: Eight confirmed and four probable cases of non-venomous snakebites were recorded. Conclusions: The symptoms produced by the snakes Helicops angulatus and Philodryas viridissima, combined with their coloration can be confused with venomous snakes (Bothrops atrox and Bothrops bilineatus), thus resulting in incorrect bothropic snakebite diagnosis. Keywords: Serpentes. Dipsadidae. Snakes. Ophidism. Envenomation. Snakes from the families Colubridae and Dipsadidae incidence of cases is recorded (56.1 per 100,000 inhabitants)2. Of are traditionally classified as non-poisonous, despite having these, bites by non-venomous snakes are also computed (Boidae, the Duvernoy's gland and the capacity for producing toxic Colubridae, and Dipsadidae) which, depending on the region, secretions, which eventually cause envenomations1. -

The Hognose Snake: a Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 1977 The Hognose Snake: A Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years M. R. Voorhies University of Nebraska State Museum, [email protected] R. G. Corner University of Nebraska State Museum Harvey L. Gunderson University of Nebraska State Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Voorhies, M. R.; Corner, R. G.; and Gunderson, Harvey L., "The Hognose Snake: A Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years" (1977). Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum. 8. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska State Museum and Planetarium 14th and U Sts. NUMBER 15JAN 12, 1977 ognose snake hunting in sand. The snake uses its shovel-like snout to loosen the soil. Hognose snakes spend most of their time above ground, but burrow in search of food, primarily toads. Even when toads are buried a foot or more in sand, hog nose snakes can detect them and dig them out. (Photos by Harvey L. Gunderson) Heterodon platyrhinos. The snout is used in digging; :tivities THE HOG NOSE SNAKE hognose snakes are expert burrowers, the western species being nicknamed the "prairie rooter" by Sand hills ranchers. The snakes burrow in pursuit of food which consists Prairie Survivor for almost entirely of toads, although occasionally frogs or small birds and mammals may be eaten. -

Habitats Bottomland Forests; Interior Rivers and Streams; Mississippi River

hognose snake will excrete large amounts of foul- smelling waste material if picked up. Mating season occurs in April and May. The female deposits 15 to 25 eggs under rocks or in loose soil from late May to July. Hatching occurs in August or September. Habitats bottomland forests; interior rivers and streams; Mississippi River Iowa Status common; native Iowa Range southern two-thirds of Iowa Bibliography Iowa Department of Natural Resources. 2001. Biodiversity of Iowa: Aquatic Habitats CD-ROM. eastern hognose snake Heterodon platirhinos Kingdom: Animalia Division/Phylum: Chordata - vertebrates Class: Reptilia Order: Squamata Family: Colubridae Features The eastern hognose snake typically ranges from 20 to 33 inches long. Its snout is upturned with a ridge on the top. This snake may be yellow, brown, gray, olive, orange, or red. The back usually has dark blotches, but may be plain. A pair of large dark blotches is found behind the head. The underside of the tail is lighter than the belly. The scales are keeled (ridged). Its head shape is adapted for burrowing after hidden toads and it has elongated teeth used to puncture inflated toads so it can swallow them. Natural History The eastern hognose lives in areas with sandy or loose soil such as floodplains, old fields, woods, and hillsides. This snake eats toads and frogs. It is active in the day. It may overwinter in an abandoned small mammal burrow. It will flatten its head and neck, hiss, and inflate its body with air when disturbed, hence its nickname of “puff adder.” It also may vomit, flip over on its back, shudder a few times, and play dead. -

Zootaxa 2173

Zootaxa 2173: 66–68 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Correspondence ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) On the status of the snake genera Erythrolamprus Boie, Liophis Wagler and Lygophis Fitzinger (Serpentes, Xenodontinae) FELIPE F. CURCIO1,2, VÍTOR DE Q. PIACENTINI1 & DANIEL S. FERNANDES3 1Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 11.461, CEP 05422-970, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, CEP 21941–590, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] The genus Erythrolamprus Boie (1826) comprises six species of Central and South American false coral snakes (Peters & Orejas-Miranda 1970; Zaher 1999; Curcio et al. 2009). It is traditionally allocated in the tribe Xenodontini (subfamily Xenodontinae), along with the genera Liophis, Lystrophis, Umbrivaga, Waglerophis and Xenodon (sensu Dixon 1980; Cadle 1984; Myers 1986; Ferrarezzi 1994; Zaher 1999). Although Xenodontini is supported by morphological and molecular evidence, phylogenetic relationships and classification within the tribe have been the subject of recent debate. Molecular phylogenetic studies have recovered clades with Erythrolamprus nested within some representatives of the genus Liophis (Vidal et al. 2000; Zaher et al. 2009), partly corroborating previous hypotheses based on morphology (e.g. Dixon 1980). Vidal et al.’s (2000) and Zaher et al.’s (2009) sampling of taxa of Erythrolamprus and Liophis is far from comprehensive, each including five species of traditional Liophis (only one of which is common to the two studies) and one species of Erythrolamprus. -

Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 78 Number 1-2 Article 11 1971 Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa J. J. Berberich University of Iowa C. H. Dodge University of Iowa G. E. Folk Jr. University of Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1971 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Berberich, J. J.; Dodge, C. H.; and Folk, G. E. Jr. (1971) "Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 78(1-2), 25-26. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol78/iss1/11 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Berberich et al.: Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in So 25 Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa J. J. BERBERICH,1 C. H. DODGE and G. E. FOLK, JR. J. J. BERBERICH, C. H . DODGE, & G. E. FOLK, JR. Overlapping ( Heterodon nasicus nasicus Baird and Girrard) is reported from of ranges of eastern and western hognose snakes in southeastern a sand prairie in Muscatine County, Iowa. Iowa. Proc. Iowa Acad. Sci., 78( 1 ) :25-26, 1971. INDEX DESCRIPTORS : hognose snake; Heterodon nasicus; H eterodon SYNOPSIS. -

Iheringia Zoologia 1

i »r> 2 E CO _ C/> co LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHIMS S3IHV 2 i ^ z « co z co z ^NouniiisNi NViNOSHims^SB avaa h li B RAR I ES^SMITHSONIAN^INSTITL <n <" — ^ ^ Z \ ^ ^ 5 co 'LIBRARIES^SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION^OIiniliSNI^NVINOSHIlWS^SaiaV ^NOIiniliSNI^NVINOSHilWS^SBiaVaan^lBRARIES^SMITHSONiAN'lNSTIU LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION^NOlinillSNI^NVINOSHlIWS^ _ I d Vi Z ^rr^ ?> 2 M ZZ CO < *N0linillSNI^NVIN0SHllWS^S3 I H VH S 11 "Yl B RAR I ES^SMITHSONIAN^INSTITU B RAR I ES SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION^NOlinillSNrNVINOSHlIWS^SB I h Vfc CO Z CO 5 Ä ^NOIinillSNI^NVINOSHlIWS'sa I d fl Vd H LI B RAR I ES^SMITHSONIAN^NSTITU oo 00 , Z J Z ES SMITHS0NIAN" |NSTITUTI0N N0linillSNl" NVIN0SHllWS S3 I HVh Z l~ 21 r* -» co *• Z —-"^ iy5 *•!/> — II L NOIlfUUSNrNVINOSHlMS S3 I U VU a *R I ES^SMITHSONIAN^INSTITUTION co z * co mm^ ^ ^ S ^ s. ^ -^ < o /£/ CO *" co 2 co 2 CO Z INSTITUTION 11I1SNI NVIN0SH1MS S3ldVdan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN J to o: o: Z -I z -J -», l ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIlfUllSNI NVIN0SH1IWS S3 1 dV^J 8 II z o ^~~^ co E co X == °° UI1SNI NVIN0SH1IWS S3IUVHail LI B RAR I ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION^ » CO Z ~v co z 2 AR I ES^SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIlfllllSNI NVINOSHlIWS^Sa I HVH 3 II co 2 co J :Z Z I SMITHSONIAN"jNSTITUTION UllSNl" NVIN0SHllWS S3 I d VU 8 II^LI B RAR ES z r- z 1 > J/ » N> — co _ co ± CO l"l ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIlfUllSNI NVIN0SH1IWS S3 I HVHS co co Z . -

From Four Sites in Southern Amazonia, with A

Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Nat., Belém, v. 4, n. 2, p. 99-118, maio-ago. 2009 Squamata (Reptilia) from four sites in southern Amazonia, with a biogeographic analysis of Amazonian lizards Squamata (Reptilia) de quatro localidades da Amazônia meridional, com uma análise biogeográfica dos lagartos amazônicos Teresa Cristina Sauer Avila-PiresI Laurie Joseph VittII Shawn Scott SartoriusIII Peter Andrew ZaniIV Abstract: We studied the squamate fauna from four sites in southern Amazonia of Brazil. We also summarized data on lizard faunas for nine other well-studied areas in Amazonia to make pairwise comparisons among sites. The Biogeographic Similarity Coefficient for each pair of sites was calculated and plotted against the geographic distance between the sites. A Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity was performed comparing all sites. A total of 114 species has been recorded in the four studied sites, of which 45 are lizards, three amphisbaenians, and 66 snakes. The two sites between the Xingu and Madeira rivers were the poorest in number of species, those in western Amazonia, between the Madeira and Juruá Rivers, were the richest. Biogeographic analyses corroborated the existence of a well-defined separation between a western and an eastern lizard fauna. The western fauna contains two groups, which occupy respectively the areas of endemism known as Napo (west) and Inambari (southwest). Relationships among these western localities varied, except between the two northernmost localities, Iquitos and Santa Cecilia, which grouped together in all five area cladograms obtained. No variation existed in the area cladogram between eastern Amazonia sites. The easternmost localities grouped with Guianan localities, and they all grouped with localities more to the west, south of the Amazon River. -

Colubrid Venom Composition: an -Omics Perspective

toxins Review Colubrid Venom Composition: An -Omics Perspective Inácio L. M. Junqueira-de-Azevedo 1,*, Pollyanna F. Campos 1, Ana T. C. Ching 2 and Stephen P. Mackessy 3 1 Laboratório Especial de Toxinologia Aplicada, Center of Toxins, Immune-Response and Cell Signaling (CeTICS), Instituto Butantan, São Paulo 05503-900, Brazil; [email protected] 2 Laboratório de Imunoquímica, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo 05503-900, Brazil; [email protected] 3 School of Biological Sciences, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO 80639-0017, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-11-2627-9731 Academic Editor: Bryan Fry Received: 7 June 2016; Accepted: 8 July 2016; Published: 23 July 2016 Abstract: Snake venoms have been subjected to increasingly sensitive analyses for well over 100 years, but most research has been restricted to front-fanged snakes, which actually represent a relatively small proportion of extant species of advanced snakes. Because rear-fanged snakes are a diverse and distinct radiation of the advanced snakes, understanding venom composition among “colubrids” is critical to understanding the evolution of venom among snakes. Here we review the state of knowledge concerning rear-fanged snake venom composition, emphasizing those toxins for which protein or transcript sequences are available. We have also added new transcriptome-based data on venoms of three species of rear-fanged snakes. Based on this compilation, it is apparent that several components, including cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRiSPs), C-type lectins (CTLs), CTLs-like proteins and snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs), are broadly distributed among “colubrid” venoms, while others, notably three-finger toxins (3FTxs), appear nearly restricted to the Colubridae (sensu stricto).