Lost Again in Shibuya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oshiage Yoshikatsu URL

Sumida ☎ 03-3829-6468 Oshiage Yoshikatsu URL http://www.hotpepper.jp/strJ000104266/ 5-10-2 Narihira, Sumida-ku 12 Mon.- Sun. 9 3 6 and Holidays 17:00 – 24:00 (Closing time: 22:30) Lunch only on Sundays and Holidays 11:30 – 14:00 (Open for dinner on Sundays and Holidays by reservation only) Irregular 4 min. walk from Oshiage Station Exit B1 on each line Signature menu とうきょう "Tsubaki," a snack set brimming Green Monjayaki (Ashitabaスカイツリー駅 Monja served with baguettes) with Tokyo ingredients OshiageOshiage Available Year-round Available Year-round Edo Tokyo vegetables, Tokyo milk, fi shes Yanagikubo wheat (Higashikurume), fl our (Ome), cabbages Ingredients Ingredients 北十間川 from Tokyo Islands, Sakura eggs, soybeans (produced in Tokyo), Ashitaba (from Tokyo Islands), ★ used used (from Hinode and Ome), TOKYO X Pork TOKYO X Pork sausage, Oshima butter (Izu Oshima Island) *Regarding seasoning, we use Tokyo produced seasonings in general, including Hingya salt. Tokyo Shamo Chicken Restaurant Sumida ☎ 03-6658-8208 Nezu Torihana〈Ryogoku Edo NOREN〉 URL http://www.tokyoshamo.com/ 1-3-20 Yokoami, Sumida-ku 12 9 3 6 Lunch 11:00 – 14:00 Dinner 17:00 – 21:30 Mondays (Tuesday if Monday is a holiday) Edo NOREN can be accessed directly via JR Ryogoku Station West Exit. Signature menu Tokyo Shamo Chicken Tokyo Shamo Chicken Course Meal Oyakodon Available Year-round Available Year-round ★ Ingredients Ingredients Tokyo Shamo Chicken Tokyo Shamo Chicken RyogokuRyogoku used used *Business hours and days when restaurants are closed may change. Please check the latest information on the store’s website, etc. 30 ☎ 03-3637-1533 Koto Kameido Masumoto Honten URL https://masumoto.co.jp/ 4-18-9 Kameido, Koto-ku 12 9 3 6 Mon-Fri 11:30 – 14:30/17:00 – 21:00 Weekends and Holidays 11:00 – 14:30/17:00 – 21:00 * Last Call: 19:30 Lunch last order: 14:00 Mondays or Tuesdays if a national holiday falls on Monday. -

ZIPAIR's December 2020 to End of March 2021 Period Tokyo-Seoul

ZIPAIR’s December 2020 to end of March 2021 period Tokyo-Seoul and Tokyo-Bangkok routes booking is now open October 30, 2020 Tokyo, October 30, 2020 – ZIPAIR Tokyo will start to sell tickets for the Tokyo (Narita) - Seoul (Incheon) and Tokyo (Narita) - Bangkok (Suvarnabhumi) routes for travel between December 1, 2020 and March 27, 2021, from today, October 30. 1. Flight Schedule Tokyo (Narita) - Seoul (Incheon) (October 25 – March 26, 2021) Flight Route Schedule Operating day number Tokyo (Narita) = ZG 41 Narita (NRT) 8:40 a.m. Seoul (ICN) 11:15 a.m. Tue., Fri., Sun. Seoul (Incheon) ZG 42 Seoul (ICN) 12:40 p.m. Narita (NRT) 3:05 p.m. Tue., Fri., Sun. Bangkok (Suvarnabhumi) – Tokyo (Narita) “one-way” Service (October 28 – March 27, 2021) Flight Route Schedule Operating day number Bangkok This service is only available from Bangkok. (Suvarnabhumi) - ZG 52 Bangkok (BKK) 11:30 p.m. Wed., Thu., Fri., Tokyo (Narita) Narita (NRT) 7:15 a.m. (+1) Sat., Sun. 2. Sales Start Flights between December 1 and March 27, 2021. October 30, 6:00 p.m. Website:https://www.zipair.net 3. Airfares (1) Seat Fare (Tokyo - Seoul route) Fare (per seat, one-way) Fare Types Effective period Age Tokyo-Seoul Seoul-Tokyo ZIP Full-Flat JPY30,000-141,000 KRW360,000-440,000 7 years and older Standard Oct. 25, 2020 JPY8,000-30,000 KRW96,000-317,000 7 years and - Mar. 26, 2021 older U6 Standard JPY3,000 KRW36,000 Less than 7 years (2) Seat Fare (Tokyo - Bangkok route) Fare (per seat, one-way) Fare Types Effective period Age Tokyo-Bangkok Bangkok-Tokyo ZIP Full-Flat THB15,000-61,800 7 years and Value older Standard Oct. -

NII Start Operation 400 Gbps Tokyo-Osaka Link to Speed Up

NEWS RELEASE December 6, 2019 NII start operation 400 Gbps Tokyo-Osaka link to speed up SINET, ultra-high speed network supporting Japan’s academic research: Putting world-leading long-distance 400 Gbps link into practical operation The National Institute of Informatics (NII, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan; Dr. Masaru KITSUREGAWA, Director General) has constructed a long-distance link with a world’s top-class transmission speed of 400 Gbps between Tokyo and Osaka as part of an academic information network, SINET5(*1). The existing SINET5 provides 100 Gbps links covering all of Japan’s prefectures. The new link has a capacity four times that of existing links. It will come into service on December 9. The purpose of constructing this 400 Gbps link is to increase the transmission capacity between the Kanto area centering on Tokyo and the Kansai area centering on Osaka and thereby to resolve the tight capacity situation amid soaring demand for data communication between the two regions where universities, research organizations, and other entities are concentrated. This implementation removes the issue about network resources being occupied by high-volume data communication and ensures stable communication. The updated infrastructure meets demands for further data increases and new high-volume data transmissions in inter-university collaborations and large research projects. Figure: General view of SINET5, in which a 400-Gbps link (shown as a red line) has been added between Tokyo and Osaka Research Organization of Information and Systems National Institute for Informatics Web: https://www.nii.ac.jp Publicity Team 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo Twitter: @jouhouken 101-8430 JAPAN facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jouhouken Direct: +81(0)3-4212-2164 FAX:+81(0)3-4212-2150 E-Mail: [email protected] SINET is a network utilized by universities and research organizations across Japan. -

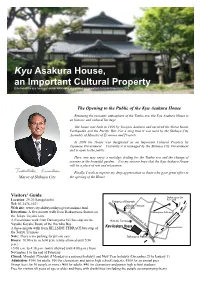

Kyu Asakura House,An Important Cultural Property

Kyu Asakura House, an Important Cultural Property Exterior of the kyu Asakura House, which was designated an Important Cultural Property in 2004 The Opening to the Public of the Kyu Asakura House Retaining the romantic atmosphere of the Taisho era, the Kyu Asakura House is an historic and cultural heritage. The house was built in 1919 by Torajiro Asakura and survived the Great Kanto Earthquake and the Pacific War. For a long time it was used by the Shibuya City Assembly of Ministry of Economy and Projects.. In 2004 the House was designated as an Important Cultural Property by Japanese Government. Currently it is managed by the Shibuya City Government and is open to the public. Here, one may enjoy a nostalgic feeling for the Taisho era and the change of seasons in the beautiful garden. It is my sincere hope that the Kyu Asakura House will be a place of rest and relaxation. Finally, I wish to express my deep appreciation to those who gave great effort to Mayor of Shibuya City the opening of the House. Visitors’ Guide Location: 29-20 Sarugakucho Tel: 03-3476-1021 Web site: www.city.shibuya.tokyo.jp/est/asakura.html Directions: A five-minute walk from Daikanyama Station on the Tokyu Toyoko Line A five-minute walk from Daikanyama Eki bus stop on the Yuyake Koyake Route of the Hachiko Bus A three-minute walk from HILLSIDE TERRACE bus stop of the Tokyu Transsés Note: There is no parking for private cars. Hours: 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. -

Work Completed on Shinjuku M-SQUARE, a New Shinjuku Station Area Landmark

March 9, 2018 For immediate release Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd. Work Completed on Shinjuku M-SQUARE, a New Shinjuku Station Area Landmark Tokyo, Japan, March 9, 2018 - Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd., a leading global real estate company headquartered in Tokyo, announced today that work finished January 31, 2018, on Shinjuku M-SQUARE, an office building project it had been working on in Shinjuku 3-Chome. Openings in this building are planned for Gucci Shinjuku on Friday, April 6, as well as for the Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation Shinjuku Branch, Shinjuku higashi Area Main Office, Shinjuku Corporate Business Office -Ⅰ,Shinjuku Corporate Business Office -Ⅱ and SMBC Nikko Securities Shinjuku-Higashiguchi Branch on Monday, May 21. Furthermore, the SMBC Trust Bank PRESTIA Shinjuku Higashiguchi Branch will open on Tuesday, July 17. This building is in an ideal location connected directly to Shinjuku Station on the Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line and provides smooth access to all major lines, including various JR lines, via an underground passage. Equipped with pedestrian-flow plans to move from below ground to above ground, as well as elevators enabling barrier-free access, the building will be open from the day’s first train to its last, contributing to activating the flow of people in the Shinjuku area. The exterior of the building on Shinjuku-dori avenue has a completely glass façade and stylish design that make it stand out even in an area with many commercial buildings. Large digital signage has been installed in the exterior space on the second floor to be utilized as highly valuable advertising space. -

Huge City Model Communicates the Appeal of Tokyo -To Be Used by City in Presentation Given to IOC Evaluation Commission

Press Release 2009-04-17 Mori Building Co., Ltd. Mori Building provides support for Olympic and Paralympic bid Huge city model communicates the appeal of Tokyo -To be used by city in presentation given to IOC Evaluation Commission- At 17.0 m × 15.3 m, Japan's largest model With Tokyo making a bid to host the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Mori Building is cooperating with the city by providing a huge model of central Tokyo for use in the upcoming tour of the IOC Evaluation Commission. This model was created with original technology developed by Mori Building; it is on display at Tokyo Big Sight. Created at 1/1000 scale, the model incorporates Olympic-related facilities that would be constructed in the city, and it presents a very appealing and sophisticated representation of near-future Tokyo. The model's 17.0 m × 15.3 m size makes it the largest in Japan, and its fine detail and high impact communicate a very real and attractive picture of Tokyo. On public view until April 30 In support of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic bid, Mori Building is providing this city model as a tool that visually communicates the city's appeal in an easy-to-understand manner. From April 17 afternoon to 30, the model will be on display to the public in the Tokyo Big Sight entrance hall. We hope that many members of the general public will see it, and that it will further increase their interest in Tokyo. Mori Building independently created city model/CG pictures as a tool to facilitate an objective and panoramic comprehension of the city/landscape. -

Face Express, a New Facial Recognition Technology for Boarding Procedures at NRT and HND Is Coming Soon ! It’S Seamless and Contactless Experience !

NEWS RELEASE 25 March 2021 Face Express, a new facial recognition technology for boarding procedures at NRT and HND is coming soon ! It’s seamless and contactless experience ! The operating companies of Narita International Airport (Narita International Airport Corporation - NAA) and Tokyo International Airport (Tokyo International Air Terminal Corporation - TIAT), will commence their trial for "Face Express”, a new boarding procedure using facial recognition technology, in April 2021. Once passengers register their facial image in Face Express, they will be able to access and proceed through subsequent procedures at the airport (check-in, baggage drop, security checkpoint entrance, boarding gate, etc.) without showing their passport and boarding pass. Its introduction will expedite seamless boarding procedures and, because most processing is touchless, it will also reduce the infection risks posed by person-to- person contact. The two airports will each commence their trial operation as below and prepare for a full launch in July. Start of trial operation : Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Participating airlines: All Nippon Airways, Japan Airlines (more airlines will participate later) Locations : [South Wing Terminal 1] Check-in Island C / Gates 51 to 57A [ Terminal 2 ]Check-in Island K / Gates 61 to 66, 71, 81 to 83, 91 to 93 • Service details are available at the following URL: https://www.narita-airport.jp/en/faceexpress/ Start of trial operation : Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Participating airlines: Airlines operating international flights at HND Locations: [Terminal 3] Check-in Islands D, E, G, H, I, J / All gates [Terminal 2*] Check-in Islands P, Q, T / All gates *All international counters are closed at present. -

Ticketing Guide

Ticketing Guide June 2021 1 Contents 1. Games Overview p2 2. Games Venue p3 3. Tickets Rules p7 4. Accessibility p8 5. Competition Schedule p9 6. Full Competition Schedule And Prices p10 Opening and Closing Ceremonies p10 Golf p41 Aquatics (Swimming) p11 Gymnastics (Artistic) p42 Aquatics (Diving) p13 Gymnastics (Rhythmic) p43 Aquatics (Artistic Swimming) p14 Gymnastics (Trampoline) p43 Aquatics (Water Polo) p15 Handball p44 Aquatics (Marathon Swimming) p17 Hockey p46 Archery p18 Judo p48 Athletics p19 Karate p50 Athletics (Marathon) (Race Walk) p21 Modern Pentathlon p51 Badminton p22 Rowing p52 Baseball p23 Rugby p53 Softball p24 Sailing p54 Basketball (3x3 Basketball) p25 Shooting p55 Basketball p26 Skateboarding(Park) p56 Boxing p28 Skateboarding(Street) p56 Canoe(Slalom) p30 Sport Climbing p57 Canoe(Sprint) p31 Surfing p58 Cycling(BMX Freestyle) p32 Table Tennis p59 Cycling(BMX Racing) p32 Taekwondo p61 Cycling(Mountain Bike) p33 Cycling(Road) p33 Tennis p62 Cycling(Track) p34 Triathlon p65 Equestrian/Eventing p35 Beach Volleyball p66 Equestrian/Dressage,Eventing,Jumping p35 Volleyball p68 Fencing p36 Weightlifting p70 Football p38 Wrestling p71 1 1. Games Overview Olympic Sports A total of 33 different sports will be contested at the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020. The 2020 Games are also the first time that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has enabled the Organising Committee to propose additional sports for that edition of the Olympic Games. The Tokyo 2020 Organising Committee proposed the five additional sports of Baseball/Softball, Karate, Skateboarding, Sport Climbing and Surfing. All five were approved by the IOC for inclusion in the Tokyo 2020 Games. sports including Karate, Skateboarding, Sport Climbing and Surfing, which will be making their Olympic debuts at the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 23 July – 8 August 2021 (17 days) 2 2. -

01 the Expansion Of

The expansion of Edo I ntroduction With Tokugawa Ieyasu’s entry to Edo in 1590, development of In 1601, construction of the roads connecting Edo to regions the castle town was advanced. Among city construction projects around Japan began, and in 1604, Nihombashi was set as the undertaken since the establishment of the Edo Shogunate starting point of the roads. This was how the traffic network government in 1603 is the creation of urban land through between Edo and other regions, centering on the Gokaido (five The five major roads and post towns reclamation of the Toshimasusaki swale (currently the area from major roads of the Edo period), were built. Daimyo feudal lords Post towns were born along the five major roads of the Edo period, with post stations which provided lodgings and ex- Nihombashi Hamacho to Shimbashi) using soil generated by and middle- and lower-ranking samurai, hatamoto and gokenin, press messengers who transported goods. Naito-Shinjuku, Nihombashi Shinsen Edo meisho Nihon-bashi yukibare no zu (Famous Places in Edo, leveling the hillside of Kandayama. gathered in Edo, which grew as Japan’s center of politics, Shinagawa-shuku, Senju-shuku, and Itabashi-shuku were Newly Selected: Clear Weather after Snow at Nihombashi Bridge) From the collection of the the closest post towns to Edo, forming the general periphery National Diet Library. society, and culture. of Edo’s built-up area. Nihombashi, which was set as the origin of the five major roads (Tokaido, Koshu-kaido, Os- Prepared from Ino daizu saishikizu (Large Colored Map by hu-kaido, Nikko-kaido, Nakasendo), was bustling with people. -

Experience Japanese Culture Our Facilities and Investment in Updating the Ho- Tel’S Infrastructure

Timeline of facility AT A GLANCE Rikisaburo Kitajima and infrastructure Location General Manager improvements Just a stone’s throw from Tokyo’s most accessible transport hub, Shinjuku Station, To enhance the quality of our products and the Keio Plaza Hotel Tokyo is ideally located Pioneers in Asia services, we are committed to the renovation of for both business and sightseeing. Experience Japanese Culture our facilities and investment in updating the ho- tel’s infrastructure. From 2003–2009, the Keio As the first skyscraper hotel in the industry, creating and Plaza Hotel Tokyo spent more than 10 billion JR Yamanote Line Japan, we met the challenge of establishing new services and yen on a large-scale renovation project, while in the of Ikebukuro Heart Tokyo successfully constructing this introducing products, which still making significant advances in the hotel’s Asakusa Narita Airport kind of high-rise tower back include a dedicated Japanese restaurant business. We continue to invest in Ueno in 1971. During the first six sake bar, karaoke room, onsite renovation every year in order to maintain the months following the hotel’s wedding chapel, universal- level of sophistication in our design and to make opening, over one million designed guest rooms for the critical upgrades to the hotel’s functions. Tochomae people came to the top floor for physically challenged, and so Hachioji Chofu Shinjuku a view of the urban landscape much more. Akihabara from an unprecedented height. This spirit of discovery Keio Line The Keio Plaza Hotel Tokyo continues to define the legacy continues to be a pioneer in of the Keio Plaza Hotel Tokyo. -

Oksana Masters Is Shifting Gears Toward Tokyo 2020 & Beijing 2022

Oksana Masters Is Shifting Gears Toward Tokyo 2020 & Beijing 2022 August 16, 2021 When Team Toyota athlete Oksana Masters tried out for Team USA for the first time in 2008, a U.S. national rowing coach said her goals were unrealistic. The coach told Masters, who is a double amputee, that she’d never row at a competitive level — she was too small and didn’t look like an athlete. “I wanted to prove that coach wrong,” she says. “A lot of kids grow up watching Michael Jordan or Serena Williams and they know they can aspire to that level. But I wanted to prove that athletes don’t have to look like them, someone tall and fit. All bodies can be athletic bodies.” Ultimately, Masters didn’t make the team as a rower for the Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games. But she stayed motivated, both in the pursuit of her personal goals and to keep pushing for visibility in Paralympic sports. “As a kid with no legs, it was hard to have a vision for myself in athletics,” she says. “Seeing is believing. You have to see it to know you can do it. That’s why it’s so important to me that the Paralympics are televised now and showcase diverse groups of athletes like never before.” Today, Masters has participated in four Paralympic Games competing in four different sports across summer and winter: rowing, Nordic skiing, biathlon and cycling. With eight medals under her belt, the versatile Paralympian has unfinished business that she’s looking to settle at Tokyo 2020 with a podium finish in cycling. -

Shibuya City Industry and Tourism Vision

渋谷区 Shibuya City Preface Preface In October 2016, Shibuya City established the Shibuya City Basic Concept with the goal of becoming a mature international city on par with London, Paris, and New York. The goal is to use diversity as a driving force, with our vision of the future: 'Shibuya—turning difference into strength'. One element of the Basic Concept is setting a direction for the Shibuya City Long-Term Basic Plan of 'A city with businesses unafraid to take risks', which is a future vision of industry and tourism unique to Shibuya City. Each area in Shibuya City has its own unique charm with a collection of various businesses and shops, and a great number of visitors from inside Japan and overseas, making it a place overflowing with diversity. With the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games being held this year, 2020 is our chance for Shibuya City to become a mature international city. In this regard, I believe we must make even further progress in industry and tourism policies for the future of the city. To accomplish this, I believe a plan that further details the policies in the Long-Term Basic Plan is necessary, which is why the Industry and Tourism Vision has been established. Industry and tourism in Shibuya City faces a wide range of challenges that must be tackled, including environmental improvements and safety issues for accepting inbound tourism and industry. In order to further revitalize the shopping districts and small to medium sized businesses in the city, I also believe it is important to take on new challenges such as building a startup ecosystem and nighttime economy.