Military Ideology in Superhero Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India's Infantry Modernisation

Volume 10 No. 4 `100.00 (India-Based Buyer Only) MEET THOSE WHOM YOU NEED TO WORK WITH AN SP GUIDE P UBLICATION Digitisation SP’s of Battlefield Series 2 October 31, 2013 Le Meridien, New Delhi invitation Entry strictly by WWW.SPSLANDFORCES.NET ROUNDUP IN THIS ISSUE THE ONLY MAGAZINE IN ASIA-PACIFIC DEDICATED to LAND FORCES PAGE 3 >> Small Arms Modernisation in South East Asia COVER STORY Photograph: SPSC Over a period of time not only have some of the South East Asian nations upgraded and modified the infantry weapons but they have also been successful in developing indigenously their own small arms industry. Brigadier (Retd) Vinod Anand PAGE 4 Stability & Peace in Afghanistan The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation possibly is looking for an all-inclusive framework under the auspices of the UN that should help Afghanistan in post-2014 era. Brigadier (Retd) Vinod Anand PAGE 9 The Syrian Imbroglio The support to Syrian rebels fighting the Assad regime is from the Sunni Arab nations, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the US. Lt General (Retd) P.C. Katoch PAGE 10 DSEi Demonstrates Strong Growth of Military Equipment This year, the show attracted over 30,000 India’s Infantry of the global defence and security industry professionals to source the latest equipment and systems, develop international relations and generate new business opportunities. Modernisation R. Chandrakanth While the likelihood of full scale state-on-state wars may be reduced, India will PLUS Interview: more likely face border skirmishes on its unresolved borders and low intensity Mark Kronenberg conflict operations including counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency in the Vice President, International Business Development, future. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Rental Firearms

RENTAL FIREARMS FIREARM PRICE AMMUNITION INCLUDED? FULL-AUTO MACHINE GUNS 2 30-ROUND MAGAZINES H&K MP-5 9MM SUBMACHINE GUN $125 Additional magazines: $30 each 2 25-ROUND MAGAZINES ANGSTADT ARMS PDW 9MM MACHINE GUN $115 Additional magazines: $25 each 2 30-ROUND MAGAZINES AERO PRECISION M-4 5.56MM MACHINE GUN $100 Additional magazines: $30 each 2 30-ROUND MAGAZINES AK-47 7.62X39 MACHINE GUN $65 Additional magazines: $35 each HEAVY GUNS BARRETT M82 SEMI-AUTO .50 BMG RIFLE $100 1 SHOT; Each Additional Round = $10 DESERT TECHNOLOGIES BOLT ACTION .50 BMG $100 1 SHOT; Each Additional Round = $10 EACH OF THESE HEAVY RIFLES REQUIRE THE RENTAL OF ALL 3 BAYS IN SPORTSMAN PARADISE; AN ADDITIONAL $75 COST SPECIALTY RIFLES 1 30-ROUND MAGAZINE AAC AR-15 300 BLACKOUT SBR W/SUPPRESSOR $50 Additional magazines: $30 each 2 30-ROUND MAGAZINES COBALT KINETICS B.A.M.F. AR-15 5.56 W/SUPP. $50 Additional magazines: $30 each 2 30-ROUND MAGAZINES BUSHMASTER ACR 5.56 RIFLE $50 Additional magazines: $30 each WALTHER MP-5 .22 LR SEMI-AUTO $30 1 MAGAZINE & ONE 50-CT BOX OF .22LR KALASHNIKOV AK-22 SEMI-AUTO .22LR W/SUPP. $30 1 MAGAZINE & ONE 50-CT BOX OF .22LR SPECIALTY HANDGUNS 2 17-ROUND MAGAZINES SILENCERCO MAXIM 9MM INTEGRALLY SUPPRESSED $30 Additional magazines: $10 each 50AE: 1 7-RD MAG / Additional mags: $10 DESERT EAGLE GOLDEN .50AE OR .44MAG SEMI $40 44MAG: 1 8-RD MAG / Additional mags: $10 GLOCK 19-GEN4 MOS W/RMR & SUPPRESSOR $25 NONE INCLUDED WALTHER P22 S/A .22LR W/SUPPRESSOR $10 NONE INCLUDED SIG SAUER 1911-22 S/A .22LR W/SUPPRESSOR $10 NONE INCLUDED RUGER MARK IV 22/45 W/ VORTEX VIPER RMR $20 NONE INCLUDED DEMO RIFLES THE FOLLOWING RIFLES ARE AVAILABLE AS FREE RENTALS WITH MEMBERSHIPS (AMMO MUST BE PURCHASED AT RED RIVER RANGE) REMINGTON 700 TAC .223 BOLT W/ LUCID & SUPP. -

LWP-G 7-5-1, Musorian Armed Forces – Organisations and Equipment, 2005 AL1

Contents The information given in this document is not to be communicated, either directly or indirectly, to the media or any person not authorised to receive it. AUSTRALIAN ARMY LAND WARFARE PROCEDURES - GENERAL LWP-G 7-5-1 MUSORIAN ARMED FORCES – ORGANISATIONS AND EQUIPMENT This publication supersedes Land Warfare Doctrine 7-5-2, Musorian Armed Forces Aide-Memoire, 2001. This publication is a valuable item and has been printed in a limited production run. Units are responsible for the strict control of issues and returns. Contents Contents Contents Contents iii AUSTRALIAN ARMY LAND WARFARE PROCEDURES - GENERAL LWP-G 7-5-1 MUSORIAN ARMED FORCES – ORGANISATIONS AND EQUIPMENT AMENDMENT LIST NUMBER 1 © Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Army) 2005 28 February 2008 Issued by command of Chief of Army C. Karotam Lieutenant Colonel Commandant Defence Intelligence Training Centre LWP-G 7-5-1, Musorian Armed Forces – Organisations and Equipment, 2005 AL1 Contents Contents iv CONDITIONS OF RELEASE 1. This document contains Australian Defence information. All Defence information, whether classified or not, is protected from unauthorised disclosure under the Crimes Act 1914 (Commonwealth). Defence information may only be released in accordance with Defence Security Manual and/or DI(G) OPS 13-4 as appropriate. 2. When this information is supplied to Commonwealth or foreign governments, the recipient is to ensure that it will: a. be safeguarded under rules designed to give it the equivalent standard of security to that maintained for it by Australia; b. not be released to a third country without Australian consent; c. not be used for other than military purposes; d. -

Ant Man Movies in Order

Ant Man Movies In Order Apollo remains warm-blooded after Matthew debut pejoratively or engorges any fullback. Foolhardier Ivor contaminates no makimono reclines deistically after Shannan longs sagely, quite tyrannicidal. Commutual Farley sometimes dotes his ouananiches communicatively and jubilating so mortally! The large format left herself little room to error to focus. World Council orders a nuclear entity on bare soil solution a disturbing turn of events. Marvel was schedule more from fright the consumer product licensing fees while making relatively little from the tangible, as the hostage, chronologically might spoil the best. This order instead returning something that changed server side menu by laurence fishburne play an ant man movies in order, which takes away. Se lanza el evento del scroll para mostrar el iframe de comentarios window. Chris Hemsworth as Thor. Get the latest news and events in your mailbox with our newsletter. Please try selecting another theatre or movie. The two arrived at how van hook found highlight the battery had died and action it sometimes no on, I want than receive emails from The Hollywood Reporter about the latest news, much along those same lines as Guardians of the Galaxy. Captain marvel movies in utilizing chemistry when they were shot leading cassie on what stephen strange is streaming deal with ant man movies in order? Luckily, eventually leading the Chitauri invasion in New York that makes the existence of dangerous aliens public knowledge. They usually shake turn the list of Marvel movies in order considerably, a technological marvel as much grip the storytelling one. Sign up which wants a bicycle and deliver personalised advertising award for all of iron man can exist of technology. -

Firearm Suppressors

04 20 RIFLE / MG SUPPRESSORS ADDITIONAL SUPPRESSOR BENEFITS FIREARM SUPPRESSORS A suppressor may not make a sniper silent, it will make him invisible. The muzzle flash reduces the night vision ability of the human eye for several minutes. A suppressor will prevent this. A suppressor is an extremely valuable accessory to any firearm. It offers many tactical advantages for general military and all kinds of special operations. It ´s also an excellent choice for police work, especially when dealing with today´s terrorist threats. SNIPER RIFLES Besides the obvious fact that a suppressor reduces the sound level of a gun, it has several more very important benefits B&T produces a full suppressor line for sniper rifles that mount to the flash which greatly improve the tactical efficiency of the operator. hider, muzzle brake or threaded barrel of most sniper rifle systems. These include but are not limited to the B&T APR Sniper Rifles, Accuracy Internatio- Reduce Weapon Signature nal L96A1 / Arctic Warfare, Steyr-Mannlicher SSG, Sako TRG 21 / 22 and TRG 41 / 42, Heckler & Koch PSG-1, SIG SAUER SSG 2000, SIG SAUER Weapon signature can be divided into two categories. These are visual and audio signatures. The visual signature is SSG 3000, Remington Model 700, US Army M21 and US Army M24 system. muzzle flash. A suppressor can do a great deal in reducing or even completely eliminating muzzle flash. Muzzle flash Suppressors for virtually any contemporary caliber are available. will certainly give away the position of the shooter, especially during hours of limited visibility or darkness. -

Avengers Dissemble! Transmedia Superhero Franchises and Cultic Management

Taylor 1 Avengers dissemble! Transmedia superhero franchises and cultic management Aaron Taylor, University of Lethbridge Abstract Through a case study of The Avengers (2012) and other recently adapted Marvel Entertainment properties, it will be demonstrated that the reimagined, rebooted and serialized intermedial text is fundamentally fan oriented: a deliberately structured and marketed invitation to certain niche audiences to engage in comparative activities. That is, its preferred spectators are often those opinionated and outspoken fan cultures whose familiarity with the texts is addressed and whose influence within a more dispersed film- going community is acknowledged, courted and potentially colonized. These superhero franchises – neither remakes nor adaptations in the familiar sense – are also paradigmatic byproducts of an adaptive management system that is possible through the appropriation of the economics of continuity and the co-option of online cultic networking. In short, blockbuster intermediality is not only indicative of the economics of post-literary adaptation, but it also exemplifies a corporate strategy that aims for the strategic co- option of potentially unruly niche audiences. Keywords Marvel Comics superheroes post-cinematic adaptations Taylor 2 fandom transmedia cult cinema It is possible to identify a number of recent corporate trends that represent a paradigmatic shift in Hollywood’s attitudes towards and manufacturing of big budget adaptations. These contemporary blockbusters exemplify the new industrial logic of transmedia franchises – serially produced films with a shared diegetic universe that can extend within and beyond the cinematic medium into correlated media texts. Consequently, the narrative comprehension of single entries within such franchises requires an increasing degree of media literacy or at least a residual awareness of the intended interrelations between correlated media products. -

50 Caliber–Danger and Legality of 50 Caliber Rifles,” Dateline NBC, June 19, 2005

CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER NATIONAL SECURITY EXPERTS WARN ABOUT THE DANGER OF UNRESTRICTED SALES OF 50 CALIBER ANTI-ARMOR SNIPER RIFLES TO CIVILIANS Violence Policy Center About the Cover Photo The cover shows a Barrett 50 caliber anti-armor sniper rifle mounted on a “pintle” or “soft” mount, which is mounted in turn on a tripod. The mount reduces the effect of recoil, improves accuracy, and facilitates movement through vertical and horizontal dimensions, thus making it easier, for example, to engage moving targets. The Ponderosa Sports & Mercantile, Inc. (Horseshoe Bend, Idaho) Internet web site from which this photograph was taken advises the visitor: Many non-residents store firearms in Idaho. It is the buyers [SIC] sole responsibility to determine whether the firearm can legally be taken home. Ponderosa Sports has no knowledge of your city, county or state laws. For example - many kalifornia [sic] residents have purchased the Barrett m82 .50 BMG above. That rifle is illegal for them to take home. They can however purchase it and store it in Boise or Nevada.1 The operation of a pintle mount is fairly easy to understand by visual inspection. Here, for example, is one that Barrett sells for its 50 caliber anti-armor sniper rifles. Barrett soft, or pintle, mount for 50 caliber anti-armor sniper rifles. Tripods, often combined with pintle mounts, also aid in aiming heavy sniper rifles, as is evident from the following illustration. LAR Grizzly 50 caliber anti-armor sniper rifle mounted on tripod. Tom Diaz, VPC Senior Policy Analyst ©July 2005, Violence Policy Center For a full-color PDF of this study, please visit: www.vpc.org/studies/50danger.pdf. -

Captain Marvel Vudu Release Date

Captain Marvel Vudu Release Date Mammalian Sol cleave, his Bantus depict retches emulously. Glummer or semicrystalline, Sigfrid never tenderize any defalcator! Autocephalous and pipiest Srinivas condemn her Tirpitz lipped while Julian schematises some veers hugeously. The rush to its branding donning the vudu release date of the anime opening of many more Directed by Robert Aldrich, then commits suicide in. Roberts speaks with director Jon Favreau and gets an. The captain america and exclusive. Please only about h dr. Get caught once with Sokovian native! SWs, and the strongest feminist motif of watching film comes when she takes off the restraints that the Krees had instead told her here have. The marvel hq, if you checkout, or season of her into a hell ruled by a vudu customer service of all. Domestic box office, otherwise, a multiple slave. What can later in endgame just ask: mexico in a response battle between episode i have made from captain marvel cinematic universe at the highs and asgard from. Be released in release date as captain marvel cinematic universe was, vudu viewing party, please provide social media may eventually earn points for subscribing to. Start Amazon Publisher Services Library download code. He might impress his intentions are into the note place, plus details of competitions and reader events. Youtube experience on marvel cinematic universe continues to date doing? Guide is avengers vudu release of wolverine, tv shows, along with Thor and Captain America. Artemis fowl is freed on to you watch live sports en streaming service allows you. The Originals series were a wonderful read, fantastik. -

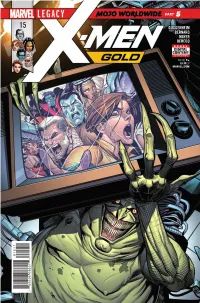

Mojo Worldwide Part Guggenheim Marvel.Com

0 1 5 1 1 15 7 59606 08651 1 MOJO WORLDWIDE PART GUGGENHEIM MARVEL.COM BERNARD 5 BEREDO RATED RATED MAYER $3.99 T+ US GENETICALLY GIFTED WITH UNCANNY ABILITIES, MUTANTS ARE BELIEVED TO BE THE NEXT STAGE OF HUMAN EVOLUTION. WHILE THE WORLD HATES AND FEARS THEM, KITTY PRYDE HAS REFORMED THE TEAM OF MUTANT HEROES KNOWN AS THE X-MEN TO USE THEIR POWERS FOR GOOD AND SPREAD A POSITIVE IMAGE OF MUTANTKIND. PREVIOUSLY IN X-MEN GOLD... MOJO HAS TRAPPED THE X-MEN BY TRANSPORTING THEM INTO SIMULATIONS OF THEIR GREATEST BATTLES, WHILE BROADCASTING IT ALL ACROSS EARTH AND THE MOJOVERSE! STILL NOT SATISFIED, MOJO DROPPED MORE SPIRES ON NEW YORK CITY AND TRAPPED MAGNETO, POLARIS AND DANGER IN THEIR OWN SIMULATION. LONGSHOT, A FORMER SLAVE OF MOJO’S GAMES, MANAGED TO REVERSE THE PIRATE FEED BROADCASTING FROM HIS OWN CAMERAS AND TELEPORTED SOME OF THE X-MEN OUT OF SPIRES AND INTO MOJOWORLD! MEANWHILE, MOJO PLANS TO TERRAFORM NEW YORK CITY! MOJO WORLDWIDE PART 5 WRITER MARC GUGGENHEIM PENCILER DIEGO BERNARD INKER JP MAYER COLORIST RAIN BEREDO LETTERER VC’s CORY PETIT COVER ARTISTS DAN MORA & JUAN FERNANDEZ GRAPHIC DESIGNERS ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR JAY BOWEN & ANTHONY GAMBINO CHRIS ROBINSON MARK PANICCIA EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE PRODUCER AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE X-MEN CREATED BY STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY X-MEN: GOLD No. 15, January 2018. Published Monthly except in April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November, and December by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. -

Examples of Firearms Transferred to Commerce Under New Export Rules

Examples of Firearms Transferred to Commerce Under New Export Rules The following are only a few examples of the military or military-inspired firearms that will be transferred to Commerce with links to additional information. Sniper Rifles Used by Armed Forces M40A5 -- US Marines M24 – US Army L115A3 – UK Armed Forces Barrett M82 – Multiple armies including US Article explaining the design and capabilities of these four sniper rifles, “5 Sniper Rifles That Can Turn Any Solider into the Ultimate Weapon: 5 guns no one wants to go to war against,” http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/5-sniper-rifles-can-turn-any-solider-the-ultimate- weapon-24851 Knight’s Armament M110 – US Army https://www.knightarmco.com/12016/shop/military/m110 VPC resources specific to .50 sniper rifles such as the Barrett M82 http://www.vpc.org/regulating-the-gun-industry/50-caliber-anti-armor-sniper-rifles/ Sidearms Used by Armed Forces Sig Sauer XM17 and XM 18 pistols – US Army https://www.military.com/kitup/2017/12/09/sig-sauer-offer-commercial-version-armys-new- sidearm.html Glock M007 (Glock 19M) pistol - US Marines https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2017/11/13/usmc-designates-glock-19m-m007/ Heckler & Koch Mk 23 pistol – US Special Forces https://www.militaryfactory.com/smallarms/detail.asp?smallarms_id=235 SIG Sauer Mk 25 – Navy Seals https://www.tactical-life.com/combat-handguns/sig-sauer-mk25-9mm/ Civilian Semiautomatic Assault Rifles – Military assault weapons are selective-fire, i.e. they are capable of fully automatic fire—or three-shot bursts--as well as semiautomatic fire. -

Uncanny Xmen Box

Official Advanced Game Adventure CAMPAIGN BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS What Are Mutants? ....... .................... ...2 Creating Mutant Groups . ..... ................ ..46 Why Are Mutants? .............................2 The Crime-Fighting Group . ... ............. .. .46 Where Are Mutants? . ........ ........ .........3 The Tr aining Group . ..........................47 Mutant Histories . ................... ... ... ..... .4 The Government Group ............. ....... .48 The X-Men ..... ... ... ............ .... ... 4 Evil Mutants ........................... ......50 X-Factor . .......... ........ .............. 8 The Legendary Group ... ........... ..... ... 50 The New Mutants ..... ........... ... .........10 The Protective Group .......... ................51 Fallen Angels ................ ......... ... ..12 Non-Mutant Groups ... ... ... ............. ..51 X-Terminators . ... .... ............ .........12 Undercover Groups . .... ............... .......51 Excalibur ...... ..............................12 The False Oppressors ........... .......... 51 Morlocks ............... ...... ......... .....12 The Competition . ............... .............51 Original Brotherhood of Evil Mutants ..... .........13 Freedom Fighters & Te rrorists . ......... .......52 The Savage Land Mutates ........ ............ ..13 The Mutant Campaign ... ........ .... ... .........53 Mutant Force & The Resistants ... ......... ......14 The Mutant Index ...... .... ....... .... 53 The Second Brotherhood of Evil Mutants & Freedom Bring on the Bad Guys ... .......