The Elgar Society JOURNAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1965 Bach Festival Program

v; lJ:) ~ ~ ~ :::: en ....~ Co! 1:: - rl i4 .... Co! Q ~ tl)" ..1::< Q Q ~ a ,E ~ ~ N ..... Q tl\ Q a ~ t-...." ~ Ill - 1:: IJ:) ~ ~ ~ ~ - Co! ,.p 1:: :+.. ~ ~ ':!' ~ e ~ 1:: ~ tn ;:; tn :.... lJ:)" -;:; a a Q .s ...... @ ...e. 1:: i4 ....e" ~ (>! .... 1:: Q • (>! ......... ..... i4 ..... 1:: Ill ~ ...e. ~ ~ :::: $::; tl\ ~ .... (>! ~ :.... M " - (>! 1:: ~ (>! ..1::< ...e. ...e. $::; ~ ~ ...!:! tl\ ~~ E (>! $::; (>! O,f (>! ..... 1:: - ....e" .... tl\ ~ - ~ ] ~ :+.. ..1::< Q $::; 1:: tl\ 2rv ~ :.... i4 Q - ~ ..a 1:: ~ ~ ~ ~ at ~ THE BACH FESTIVAL COUNCIL PROGRAM NOTES Dr. Russell Hammar, Director Dr. \Veimer K. Hicks, Honorary Chairman Miss Barbara \Veller, Administrative Secretary by Lawrence R. Smith Dr. James Miller, Honorary Member Dr. Henry Overley, Director Emeritus First Concert Dr. Harold Harris, Executive Co-Chairman ( 1962-65) Mrs. R. Bowen Howard, Executive Co-Chairman ( 1963-66) The fifth of Bach's six Brandenburg Concertos displays as dramatically as any other work his intense mastery in fusing the traditions of the past, which he derived from the works of the ARTISTS COMMITTEE PATRON-SPONSOR COMMITTEE Venetian masters; the currents of his own time, in which his greatest single inRuence was from Mr. E. Lawrence Barr 1962-65 Mrs. Lester Start, Chairman Vivaldi; and his own forward-looking inventiveness. The colorful instrumentation of the work, Dr. J. M. Calloway Mrs. Russell Carlton 1963-66 using a string instrument, the violin; a woodwind, the flute; and a keyboard instrument, the Mrs. Maynard Conrad 1964-67 Mr. Neill Currie 1964-67 harpsichord, as the concertina group against the mass of the string ripieno, reflects the polychoral Mrs. Marion Dunsmore 1964-67 Mrs. John Correll 1964-67 productions of Gabrieli and his followers at Venice at the juncture of the Renaissance and Mrs. -

EVELYN BARBIROLLI, Oboe Assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, Harpsichord the SHEPHERD QUARTET

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Rice University EVELYN BARBIROLLI, oboe assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, harpsichord THE SHEPHERD QUARTET Wednesday, October 20, 1976 8:30P.M. Hamman Hall RICE UNIVERSITY Samuel Jones, Dean I SSN 76 .10. 20 SH I & II TA,!JE I PROGRAM Sonata in E-Flat Georg Philipp Telernann Largo (1681 -1767) Vivace Mesto Vivace Sonata in D Minor Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach Allegretto (1732-1795) ~ndante con recitativi Allegro Two songs Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Das Lied der Trennung (1756-1791) _...-1 Vn moto di gioia mi sento (atr. Evelyn Rothwell) 71 u[J. 0...·'1. {) /llfil.A.C'-!,' l.raMc AI,··~ l.l. ' Les Fifres Jean Fra cois Da leu (1682-1738) (arr. Evelyn Rothwell) ' I TAPE II Intermission Quartet Massonneau Allegro madera to (18th Century French) Adagio ' Andante con variazioni Quintet in G Major for Oboe and Strings Arnold Bax Molto mo~erato - Allegro - Molto Moderato (1883-1953) Len to espressivo Allegro giocoso All meml!ers of the audiehce are cordially invited to a reception in the foyer honoring Lady Barbirolli following this evening's concert. EVELYN BARBIROLLI is internationally known as one of the few great living oboe virtuosi, and began her career th1-ough sheer chance by taking up the study qf her instrument at 17 because her school (Downe House, Newbury) needed an oboe player. Within a yenr, she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. Evelyn Rothwell immediately establis71ed her reputation Hu·ough performances and recordings at home and abroad. -

The Development of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Music Department Honors Papers Music Department 1-1-2011 The evelopmeD nt of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams Currie Huntington Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp Recommended Citation Huntington, Currie, "The eD velopment of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams" (2011). Music Department Honors Papers. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp/2 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH CHORAL STYLE IN TWO EARLY WORKS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS An Honors Thesis presented by Currie Huntington to the Department of Music at Connecticut College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field and for the Concentration in Historical Musicology Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 5th, 2011 ABSTRACT The late 19th century was a time when England was seen from the outside as musically unoriginal. The music community was active, certainly, but no English composer since Handel had reached the level of esteem granted the leading continental composers. Leading up to the turn of the 20th century, though, the early stages of a musical renaissance could be seen, with the rise to prominence of Charles Stanford and Hubert Parry, followed by Elgar and Delius. -

View/Download Liner Notes

HUBERT PARRY SONGS OF FAREWELL British Choral Music remarkable for its harmonic warmth and melodic simplicity. Gustav Holst (1874-1934) composed The Evening- 1 The Evening-Watch Op.43 No.1 Gustav Holst [4.59] Watch, subtitled ‘Dialogue between the Body Herbert Howells (1892-1983) composed his Soloists: Matthew Long, Clare Wilkinson and the Soul’ in 1924, and conducted its first memorial anthem Take him, earth, for cherishing 2 A Good-Night Richard Rodney Bennett [2.58] performance at the 1925 Three Choirs Festival in late 1963 as a tribute to the assassinated 3 Take him, earth, for cherishing Herbert Howells [9.02] in Gloucester Cathedral. A setting of Henry President John F Kennedy, an event that had moved Vaughan, it was planned as the first of a series him deeply. The text, translated by Helen Waddell, 4 Funeral Ikos John Tavener [7.41] of motets for unaccompanied double chorus, is from a 4th-century poem by Aurelius Clemens Songs of Farewell Hubert Parry but only one other was composed. ‘The Body’ Prudentius. There is a continual suggestion in 5 My soul, there is a country [3.52] is represented by two solo voices, a tenor and the poem of a move or transition from Earth to 6 I know my soul hath power to know all things [2.04] an alto – singing in a metrically free, senza Paradise, and Howells enacts this by the way 7 Never weather-beaten sail [3.22] misura manner – and ‘The Soul’ by the full his music moves from unison melody to very rich 8 There is an old belief [4.52] choir. -

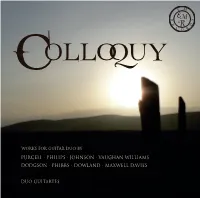

'Colloquy' CD Booklet.Indd

Colloquy WORKS FOR GUITAR DUO BY PURCELL · PHILIPS · JOHNSON · VAUGHAN WILLIAMS DODGSON · PHIBBS · DOWLAND · MAXWELL DAVIES DUO GUITARTES RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872–1958) COLLOQUY 10. Fantasia on Greensleeves [5.54] JOSEPH PHIBBS (b.1974) Serenade HENRY PURCELL (1659–1695) 11. I. Dialogue [3.54] Suite, Z.661 (arr. Duo Guitartes) 12. II. Corrente [1.03] 1. I. Prelude [1.18] 13. III. Liberamente [2.48] 2. II. Almand [4.14] WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDING 3. III. Corant [1.30] 4. IV. Saraband [2.47] PETER MAXWELL DAVIES (1934–2016) Three Sanday Places (2009) PETER PHILIPS (c.1561–1628) 14. I. Knowes o’ Yarrow [3.03] 5. Pauana dolorosa Tregian (arr. Duo Guitartes) [6.04] 15. II. Waters of Woo [1.49] JOHN DOWLAND (1563–1626) 16. III. Kettletoft Pier [2.23] 6. Lachrimae antiquae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.56] STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) 7. Lachrimae antiquae novae (arr. Duo Guitartes) [1.50] 17. Promenade I [10.04] JOHN JOHNSON (c.1540–1594) TOTAL TIME: [57.15] 8. The Flatt Pavin (arr. Duo Guitartes) [2.08] 9. Variations on Greensleeves (arr. Duo Guitartes) [4.22] DUO GUITARTES STEPHEN DODGSON (1924–2013) Dodgson studied horn and, more importantly to him, composition at the Royal College of Music under Patrick Hadley, R.O. Morris and Anthony Hopkins. He then began teaching music in schools and colleges until 1956 when he returned to the Royal College to teach theory and composition. He was rewarded by the institution in 1981 when he was made a fellow of the College. In the 1950s his music was performed by, amongst others, Evelyn Barbirolli, Neville Marriner, the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble and the composer Gerald Finzi. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Oboe Trios: an Annotated Bibliography

Oboe Trios: An Annotated Bibliography by Melissa Sassaman A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Martin Schuring, Chair Elizabeth Buck Amy Holbrook Gary Hill ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2014 ABSTRACT This project is a practical annotated bibliography of original works for oboe trio with the specific instrumentation of two oboes and English horn. Presenting descriptions of 116 readily available oboe trios, this project is intended to promote awareness, accessibility, and performance of compositions within this genre. The annotated bibliography focuses exclusively on original, published works for two oboes and English horn. Unpublished works, arrangements, works that are out of print and not available through interlibrary loan, or works that feature slightly altered instrumentation are not included. Entries in this annotated bibliography are listed alphabetically by the last name of the composer. Each entry includes the dates of the composer and a brief biography, followed by the title of the work, composition date, commission, and dedication of the piece. Also included are the names of publishers, the length of the entire piece in minutes and seconds, and an incipit of the first one to eight measures for each movement of the work. In addition to providing a comprehensive and detailed bibliography of oboe trios, this document traces the history of the oboe trio and includes biographical sketches of each composer cited, allowing readers to place the genre of oboe trios and each individual composition into its historical context. Four appendices at the end include a list of trios arranged alphabetically by composer’s last name, chronologically by the date of composition, and by country of origin and a list of publications of Ludwig van Beethoven's oboe trios from the 1940s and earlier. -

Download the 2019 Festival Programme

30 MAY - 2 JUNE 2019 ELGAR FESTIVAL KENNETH WOODS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR JULIAN LLOYD WEBBER PATRON CONCERTS, EVENTS, EXHIBITS AND ACTIVITIES FOR ELGAR FANS OF ALL AGES OFFICIAL PROGRAMME EF 2019 Programme Booklet v10.indd 2 24/05/2019 12:29 FESTIVAL SUPPORTERS The Elgar Festival is hugely grateful to the following organisations and individuals for their most generous support of the 2019 Festival: Worcester City Council is proud to support the 2019 Elgar Festival. The Festival provides a unique opportunity to celebrate Worcester’s rich heritage, attracting national and international recognition. Bernarr John S Cohen Rainbow Trust Foundation Alan Woodfield Charitable Trust Arthur Hilary Reynolds Elgar BOX OFFICE: www.elgarfestival.org / Worcester Live 01905 611427 / on the door where available EF 2019 Programme Booklet v10.indd 1 24/05/2019 12:29 WELCOME Welcome to the 2019 Elgar Festival. Welcome to this year’s Elgar Festival in This has been a year of remarkable Worcester for a programme which we growth and rapid change for the festival, hope has something in it for everyone. and I’m incredibly grateful to our Our aim at the Elgar Festival is to make committee members, trustees, Elgar and his music more accessible, more partners and supporters. available and more relevant to audiences of every age and background. So this year we have Together, we’ve managed to more than double the scope expanded the event to four days and lined up a range of of the festival, and hugely increase our level of community activities and concerts to deliver just that - Elgar engagement, work with young people and outreach, in for Everyone! addition to producing world-class concerts worthy of our namesake. -

Journal September 1988

The Elgar Society JOURNAL SEPTEMBER •i 1988 .1 Contents Page Editorial 3 Articles: Elgar and Fritz Volbach 4 -i Hereford Church Street Plan Rejected 11 Elgar on Radio 3,1987 12 Annual General Meeting Report and Malvern Weekend 13 News Items 16 Concert Diary 20 Two Elgar Programmes (illustrations) 18/19 Record Review and CD Round-Up 21 News from the Branches 23 Letters 26 Subscriptions Back cover The editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. The cover portrait is reproduced by kind permission of RADIO TIMES ELGAR SOCIETY JOURNAL ISSN 0143-1269 2 /■ The Elgar Society Journal 104 CRESCENT ROAD, NEW BARNET, HERTS. EN4 9RJ 01-440 2651 EDITORIAL Vol. 5, no. 6 September 1988 The first weekend in June (sounds like a song-title!) was one of the most enjoyable for Society members for some years. At least it was greatly enjoyed by those who attended the various events. Structured round the AGM in Great Malvern, the committee were the first to benefit from the hospitality of Lawnside. We met in the Library, passing first the awful warning “No hockey sticks or tennis racquets upstairs” (and we didn’t take any), and we were charmingly escorted round the somewhat confusing grounds and corridors by some of the girls of the school. After a lunch in the drawing room where the famous grand piano on which Elgar & GBS played duets at that first Malvern Festival so long ago, was duly admired (and played on), we went to the main school buildings for the AGM. -

Join the American Friends of the Three Choirs Festival About the Three Choirs Festival

JOIN THE AMERICAN FRIENDS OF THE THREE CHOIRS FESTIVAL ABOUT THE THREE CHOIRS FESTIVAL Having recently celebrated its 300th anniversary, the Three Choirs Festival is the world’s oldest classical music festival, presenting the world’s finest choral music. The cathedral choirs of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester, the 150-voice Three Choirs Festival Chorus and the Philharmonia Orchestra are showcased in a week- long musical celebration that rotates annually between the three cathedrals, nestled in the heart of the English countryside. Festival concerts are performed in the cathedrals themselves, offering American audiences an opportunity to experience the finest classical music in some of England’s most magnificent medieval buildings, where the world’s leading singers and musicians perform annually. © Paul Burns HRH The Prince of Wales, President of the Three Choirs Festival Association, meets choristers of the Three Cathedral Choirs at the reception which he hosted at Buckingham Palace in November 2015 to mark the 300th anniversary of the festival 2 Three Choirs American Friends THE AMERICAN ‘FRIENDS’ Created in 2014, The American Friends of the Three Choirs Festival was established to expand festival audiences, support the work of the Festival, publicize its activities, and provide sponsorship for its work. The American Friends is a registered Internal Revenue Service 501(c)3 nonprofit organization and contributions to it are tax-deductible. WHO WE ARE The American Friends of the Three Choirs Festival encompass individuals from across America: singers, retirees, church musicians, educators, Choral Evensong enthusiasts and those who desire musical or spiritual renewal. Each of us shares a love of music, an appreciation of England, and a desire to meet like-minded individuals. -

Symphony Hall, Boston Huntington and Massachusetts Avenues

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephones \ Ticket Office ) g^ g y \4d2 Branch Exchange ( Administration Offices ) ©e SjimphonjOre INCORPORATED THIRTY-EIGHTH SEASON, 1918-1919 HENRI RABAUD, Conductor LSI Mi WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 13 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 14 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INCORPORATED W. H. BRENNAN, Manager G. E. JUDD, Assistant Manager 281 "The world needs music more when it's in trouble than at any other time. And soldiers, and the mothers and wives and sweethearts and children of soldiers get more of the breath of life from music than the man on the street has any notion of."—JOHN McCORMACK MUSIC is an essential of every well-regulated home. It is a factor of vital importance in the education of the children, an unending source of inspiration and recreation for the growing gener- ation, a refining, cultivating influence touching every member of the family. It is the common speech that is understood by all, that appeals to everybody, that enlists the sympathies of man, woman and child, of high and low, of young and old, in every walk of life. The PIANO is the universal musical instrument of the home, the instrument that should be in every household. And the greatest among pianos is the STEINWAY, prized and cherished throughout the wide world by all lovers of good music. Or, in the words of a well-known American writer: "Wherever human hearts are sad or glad, and songs are sung, and strings vibrate, and keys respond to love's caress, there is known, respected, revered—loved—the name and fame of STEINWAY." Catalogue and prices on application Sold on convenient payments Old pianos taken in exchange Inspection invited 1INWAY & SOMS, STEINWAY Hi 107-109 EAST 14th STREET. -

London, 1930 a Musical Evening at the Home of Miss Harriet Cohen -If

London, 1930 A Musical Evening At The Home Of Miss Harriet Cohen Christi Amonson, Soprano as Dora Stevens John Milbauer, Pianist as Henry Cowell Robert Swensen, Tenor as John Coates Steven Moeckel, Violinist as Fritz Kreisler Paula Fan, Pianist as Harriet Cohen GUEST ARTIST CONCERT SERIES KATZIN CONCERT HALL MONDAY, MARCH 31, 2008 • 7:30 PM MUSIC -if-ferbergerCollege of the Arts ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Soprano Christi Amonson (Dora Stevens Foss) has appeared in leading roles with Opera Program Delaware, Lyric Opera San Antonio, Chautauqua Opera, Lake George Opera, Taconic Opera, Opera Intimate at Lincoln Center and the Opera Company of Brooklyn. She also toured as Naughty Marietta with Rockwell Productions. In 2006 Ms. Amonson won 2'd A Welcome by Miss Cohen place in the International Classical Singer Competition. She is also a Liederkranz Competition Winner, a Regional Finalist in the Metropolitan Opera National Council The Tides of Manaunaun Henry Cowell Auditions and a recipient of the Arlene Auger Award. Her recent concert performances Mr. Cowell include the Ortiz Music Festival in Alamos, Mexico, Messiah with the Las Vegas Desert Chorale, the Brahms Requiem with the Concordia Orchestra, Mirth in Handel's LAllegro with the Bronx Arts Ensemble at the NY Botanical Gardens, and Lincoln Center's Three Songs William Walton Broadway Dozen. Ms. Amonson earned her MM at the Manhattan School of Music and her Daphne BM at the University of Idaho. She is currently a doctoral candidate at the University of Through Gilded Trellises Arizona, where she also serves as a Graduate Teaching Assistant. Old Sir Faulk Pianist John Milbauer (Henry Cowell) has performed frequently across the Americas, Miss Stevens and Miss Cohen Europe and Asia, and his concerts have been broadcast on radio and television stations on three continuents.