Evaluating Fijian Outer Island Village Reporting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Within 1Km Radius from the Evacuation Center Evacaution Site Location Division Province Wainaloka Church Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is

1 Population Within 1km Radius from the Evacuation Center Evacaution Site Location Division Province Wainaloka Church Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nasesara Community Hall, Motoriki Is. Motoriki Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Savuna Community Hall, Motoriki Is. Motoriki Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Tokou Community Hall, Ovalau Is. Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Naikorokoro Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Korovou Community Hall, Levuka Levuka, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Ovalau Eastern Lomaiviti Levuka Vakaviti Community Hall, Levuka Levuka, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Ovalau Eastern Lomaiviti Taviya Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Waitovu Community Hall, Ovalau Is. Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Somosomo Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Sawaieke Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nawaikama Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Lovu Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Lamiti Village Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vanuaso Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Nacavanadi Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vadravadra Community Hall, Gau Is. Gau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Kade Community Hall, Koro Is. Koro Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern, Viti-Levu Eastern Lomaiviti Tovulailai Community Hall, Nairai Is. Nairai Is. Lomaiviti Grp, Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vagadaci Village Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. Lomaiviti Prov. Eastern Eastern Lomaiviti Vuma Village Community Hall, Ovalau Ovalau Is. -

SITUATION REPORT 67 of 09/03/2016

NATIONAL EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT 67 of 09/03/2016 The purpose of this report is to provide the update on the current operations undertaken after TC Winston. This Situation Report is issued by the National Emergency Operation Centre and covers the period from 1600hrs - 2400 hours, 09/03/2016. Updates in this report summarise all reports and briefs submitted from various EOC’s in the four divisions. 1.0 NATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS Further to the current overall national damage assessments conducted by the four divisions and sectoral agencies, damage incurred quantified to a magnitude of $476.8m, however progressively this is subject to change after a series of progressive detailed assessments across all sectoral agencies and the outcome of damage assessments by the DDA Teams deployed by the four divisions. A total of 545 active evacuation centers exist nationwide with the Eastern Division recording the highest with a record of 325 evacuation centers, Western Division has 196 evacuation centers while the Northern Division has 34 evacuation centers. A total of 17953 national evacuees population is recorded as the current total number of evacuees nationwide A total of 306 schools is affected with 23 schools closed for repairs and A total of 16 schools are currently used as evacuation centers occupied by 666 evacuees nationwide. 7 schools in the Western Division in the Ra Province and 9 schools in the Eastern Division, 8 in Lomaiviti and 1 in the Lau Province. Local donations assistance received, quantify to a tune of $4m while internationally we have received more than $50m in cash and kind. -

Fiji Tc Winston Flash Appeal Final.Pdf (English)

Fiji - Tropical Cyclone Winston Contact UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Regional Office for the Pacific Level 5, Kadavu House Victoria Parade, Suva, Fiji Email: [email protected] Phone: (679) 331 6760 Front Cover Photo: UNICEF/2016/Sokhin 2 Fiji – Tropical Cyclone Winston This document is produced by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian 3 Affairs in collaboration with humanitarian partners in support of the national government. It covers the period from 21 February to 21 May 2016 and is issued on 4 March 2016. Fiji - Tropical Cyclone Winston FIJI: AN OVERVIEW OF THE CRISIS Tropical Cyclone Winston, the most powerful cyclone While comprehensive damage data is still being to strike Fiji in recent time, cut a path of destruction collected, the Government’s initial reports indicate across the country on 20 and 21 February 2016. The varying levels of destruction, with up to 100 per cent eye of the Category 5 cyclone packed wind bursts of of buildings destroyed on some islands. Based on up to 320 kilometres per hour. The cyclone tracked evacuation centre figures and currently available west across the country, causing widespread damage data, approximately 24,000 houses have damage in all four divisions – Eastern, Northern, been damaged or destroyed, leaving an estimated Western and Central. It affected up to 350,000 53,635 people (six per cent of the total people (170.000 female and 180,000 male) - population) in almost 1,000 evacuation centres. equivalent to 40 per cent of Fiji’s population. This Subsistence agriculture plays an important role in includes 120,000 children under the age of 18 Fijian’s food security and livelihoods. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Cyclone Winston Fiji

UNICEF PACIFIC CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT Reporting Period 3-4 March 2016 Cyclone Winston Fiji Humanitarian Situation Report #6 ©UNICEF/2016/Sokhin Photo: Water tanks are a vital source of rural life in Fiji. This is just one of many destroyed by As of 4 March 2016 Cyclone Winston. UNICEF prioritises provision of clean safe drinking water and sanitation supplies to prevent the spread of disease. 120,000 Estimated # of children likely to have been Highlights moderately to severely affected (40% of child population) Category 5 Cyclone Winston, the strongest cyclone to ever hit Fiji and with some of the highest wind speeds at landfall ever recorded globally, severely affected around 40% of the population. 350,000 Estimated # of people likely to have been US$ 38.6 million Flash Appeal has been launched, including moderately to severely affected (40% of US$ 7.1 million for UNICEF projects. total population) An estimated 29,000+ people are living in 722 evacuation centres, Up to 250,000 people in need of including in 71 schools (Evacuation centres in Central Division WASH assistance due to electricity, closed). water and sewerage service disruptions UNICEF supplies have provided safe drinking water for over 26,000 people and are assisting 6,000 students to return to school. UNICEF Appeal within A ship with school and WASH supplies from UNICEF Vanuatu has UN Flash Appeal arrived in Suva Harbour; supplies from UNICEF Solomon Islands US$ 7.1 million being packed for shipping to Fiji; Emergency Charter Flight with health and school supplies arriving on 7 March. UNICEF’s response with partners US$ 369,849 of UNICEF supplies pre-positioned in Fiji have been provided to the Government of Fiji and are being distributed to the most affected people. -

The Case of the Fiji Islands

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 12-13-2011 Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands Sudarsan Kant University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kant, Sudarsan, "Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands" (2011). Dissertations. 395. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/395 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands By Sudarsan Kant A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Missouri-St. Louis In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science November 15, 2011 Advisory Committee Kenneth Thomas, PhD., (Chair) Nancy Kinney, Ph.D. Eduardo Silva, Ph.D. Daniel Hellinger, Ph.D. Abstract . Prevailing theories have failed to take into account the development of policy and institutions in microstates that are engineered to attract investments in areas of comparative advantage as these small islands confront the challenges of globalization and instead have emphasized migration, remittances and foreign aid (MIRAB) as an explanation for the survival of microstates in the global economy. This dissertation challenges the MIRAB model as an adequate explanation of investment strategy in microstates and argues that comparative advantage is a better theory to explain policy behavior of microstates. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

FIJI LEVUKA CONTACT • Suliana Sandys • E-Mail

FIJI LEVUKA CONTACT Suliana Sandys e-mail : [email protected] homepage : www.levukatowncouncil.com Geographical Location and Population Levuka is a town on the eastern coast of the Fijian island of Ovalau, in Lomaiviti Province, in the Eastern Division of Fiji. It was formerly the Capital of Fiji. The town was planned by the British engineers and 3 years after cession, the town ordinance of 1877 was passed giving Levuka residence the right to govern the town. The township is situated on the eastern coast of Ovalau, in the Lomaiviti Province, in the Eastern Division of Fiji. 17.6840° South and 178.8401°East. Formerly the capital of Fiji, Levuka is situated on a narrow strip of land between the sea and the steep hills on the eastern side of the island. Levuka developed as an entreport and commercial centre for Fiji in the 1860’s amidst political turmoil. On October 1874, Fiji was ceded to Great Britain and Levuka became the capital. The Government administration was shifted to Suva in 1881 and Levuka’s economy waned. The urban population is 1,131 and peri-urban 3,266. History The first capital of Fiji, Levuka was founded as a whaling settlement in 1830. The cotton boom in the 1860’s brought new settlers, and groups of businessmen followed as the cotton, coconut and tea trades flourished in the surrounding islands. Levuka grew into the hub of the South Pacific until Suva was established as the capital in 1877. The port town of Levuka is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a rare example of a late colonial port town that was influenced in its development by the indigenous community which continued to outnumber the European settlers. -

Fiji's Gender Equality Commitments and the Itaukei

Fiji’s Gender Equality Commitments and the iTaukei Village (General) By-Law, 2016 Roshika Deo 20 July 2018 Introduction iTaukei Village By-Laws was first introduced in Fiji during the colonial era in 1875. In 2010, pursuant to the iTaukei Affairs Act the military regime re-introduced the draft iTaukei Village (General) By-Laws, with the aim to protect and promote the indigenous culture, leadership and values. However this was subsequently shelved amongst criticism and concern over its content. In October 2016, the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs again introduced a version of the draft Village By-Laws and started consultations in villages. In January 2018, the process was suspended and the Village By-Laws shelved. This paper will outline some of the key elements of the process undertaken with the 2016 draft Village By-Laws and how its content fails to uphold the gender equality commitments made by the State. It will explore how the 2016 draft Village By-Laws is perpetuating discrimination and gender inequality. Key Elements of the Development of the Village By-Laws A ‘scoping study’ was carried out in 2011 to inform the 2010 draft Village By-Laws. During this ‘scoping study’ government and non-government stakeholders were consulted, however information is not available on which government agencies and non-government stakeholders participated.1 During this time, the Ministry of iTaukei Affairs stated the village by-laws would be guided by State obligations and commitments under international laws and declarations; and in the event of any conflict over rights, an effective and inclusive dialogue will be taken to reconcile these rights. -

Koro Island South - FIJI Area of Interest ! Aerodrome Unit of Measurement Total in AOI Settlements £ Estimated Wind Storm - Pre-Event Situation " Bridge No

GLIDE number: TC-2016-000014-TON Activation ID: EMSR155 Legend Product N.: 06KOROISLANDSOUTH, v1, English General Information Transportation Exposure within the AOI r Koro Island South - FIJI Area of Interest ! Aerodrome Unit of measurement Total in AOI Settlements £ Estimated Wind storm - Pre-event situation " Bridge No. of inhabitants 219 ! Populated Place population 05 SOUTH Reference Map Local Road PACIFIC Settlements Residential No. 489 OCEAN Residential Runway Religious No. 2 SOUTH Cartographic Information Agricultural PACIFIC Fiji Aerodrome Transportation No. 2 (! OCEAN ^Suva Educational Nasau 1:10000 Full color ISO A1, medium resolution (200 dpi) Educational No. 5 06 Religious Agricultural No. 2 0 0.2 0.4 0.8 km Transportation Transportation Local roads km 11.3 Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 60S map coordinate system Aerodrome ha 10.5 3 Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Runway ha 7.3 km Bridges No. 5 756000 757000 758000 759000 760000 761000 179°24'30"E 179°25'0"E 179°25'30"E 179°26'0"E 179°26'30"E 179°27'0"E 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 8 8 0 0 8 8 S N! asau " 0 3 ' 8 1 ° S " 7 0 1 £ 3 ' 8 1 ° 7 " £ " 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 4 8 8 0 0 8 8 S " 0 ' 9 1 ° 7 S 1 " 0 ' 9 1 ° 7 1 "£ 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 3 8 8 0 0 8 8 S " 0 3 ' 9 1 ° S 7 " 1 0 3 ' 9 1 ° 7 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 S " 2 2 0 ' 8 8 0 0 0 2 ° 8 8 7 S " 1 0 ' 0 2 ° 7 1 !Namacu "£ S " 0 3 ' 0 0 0 2 0 0 ° S 0 0 7 " 1 0 1 1 3 ' 8 8 0 0 0 2 ° 8 8 7 1 !r Koro Airport S " 0 ' 1 2 ° 7 S 1 " 0 ' 1 0 0 2 ° 0 0 7 0 0 1 0 0 8 8 0 0 8 "£ 8 S " 0 3 ' 1 2 ° S " 7 0 1 3 ' 1 2 ° 7 179°24'30"E 179°25'0"E 179°25'30"E 179°26'0"E 179°26'30"E 179°27'0"E 1 756000 757000 758000 759000 760000 761000 Map Information Data Sources Disclaimer Relevant date records On 19 February at 00:00 (UTC), the centre of Tropical Cyclone WINSTON was located in the south Pleiades-1A © CNES (2016), distributed by Airbus DS (acquired on 15/07/2014 22:33 UTC, GSD Products elaborated in this Copernicus EMS Rapid Mapping activity are realized to the best of our Event 20/02/2016 Situation as of NA pacific 130 km north-west of Vava'u (Tonga). -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

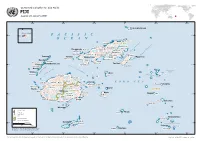

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

P a C I F I C O C E

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific FIJI Issued: 20 January 2008 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W Thikombia Island 177° Nalele Rotuma Island 16°S PACIFIC 16°S 12°30’ Rotuma Sumi OCEAN Namukalau Nambouono Vunivatu NORTHERN Nanduri Namboutini Nayarambale Napuka Yangganga Navindamu Labasa Nailou Yangganga Rabi Channel Korotasere Nakarambo Savu Sau Nawailevu Taveun i Mate i Vanuabalavu Riqold Channel Mbangasau t i Matei Yasawa a Yandua r Nggamea Vanua Levu t Qeleni Cicia S Ndenimanu o Nacula Ndaria o m o s Waiyevo Navotua Waisa m S o Matacawalevu Matathawa Levu Rave-rave Taveuni 17°S Yaqeta VATU-I-RA CHANNELThavanga 17°S Somosomo Navakawau UP RO Naviti G A W A EXPLORING S Waya S ISLES A Y Koro Nalauwaki NORT Thikombia BLIGH WATER Togow ere Koro HERN LAU Tavua Makongai GRO Nasau UP Nayavutoka Vanuakula Lautoka Navala Navai Ovalau KORO SEA Bureta Levuka Tu vu th a Tuvutha Mala WESTERN Nayavu Lawaki Malololailai Nadi Wairuarua Lovoni Bukuya Nairai Malolo Vunindawa Saweni Korovou EASTERN Momi Viti Levu CENTRAL Narewa Dromuna Ngau 18°S Naraiyawa Nayau Liku 18°S Namosi Nausori Bega Ngau Sigatoka Navua Vatukarasa SUVA e Levuka Lakemba ssag Pa qa Vanuavatu Be Waisomo Mbengga National Capital City, Town Moala Moala Major Airport River Namuka Llau Provincial Boundary Namuka International Boundary Vabea 0 20 40 Kilometers Kandavu 19°S Soso 19°S Nukuvou SOUTHERN LAU GROUP 0 20 40 Miles Kandavu Fulanga Ongea Projection: World Cylindrical Equal Area Nasau Andako Matuku Monothaki Map data sources: Global Discovery, FAO 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W The names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Map Ref: OCHA_FJI_Country_v1_080120.