Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 119 (April 2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloads/Dec2018/Harpercollins, Oops

oops 20 Life Lessons from the Fiascoes That Shaped America MARTIN J. SMITH and PATRICK J. KIGER To William Leford Smith,M.J.S whose. dimming eyes still see the humor in almost everything To Beastboy P.and J.K his. momster Good judgment is usually the result of experience. And experience is frequently the result of bad judgment. —An attorney in a lawsuit involving Boston’s John Hancock Tower, after the skyscraper’s windows fell out Some said I couldn’t sing, but no one could say I didn’t sing. —Florence Foster Jenkins, widely recognized as the worst opera diva ever contents Introduction The Joy of Oops ix Lesson #1 READ THE FINE PRINT The Eroto- Utopians of Upstate New York John Humphrey Noyes’s sexually adventurous Perfectionist commune was one of the most successful utopian religious groups in 19th-century Amer- ica. Alas, the devil was in the details. { 1 } Lesson #2 ACCENTUATE THE POSITIVE How Thomas Edison Invented Trash Talk Why would one of America’s iconic inventors publicly electrocute a full- grown carnival elephant? The answer reveals a little- known story of ego, failure, and the moment when America began “going negative.” { 13 } Lesson #3 BEWARE SOLUTIONS THAT CREATE NEW PROBLEMS The Global Underarm Deodorant Disaster Thomas Midgley Jr. was among America’s greatest problem solvers. Unfor- tunately, his landmark “Eureka!” moments had an echo that sounded a lot like “Oops!” { 27 } CONTENTS v Lesson #4 BAD RESULTS TRUMP GOOD INTENTIONS Kudzu: A Most Tangled Tale What began as a well- intentioned effort to stop soil erosion in the American South became a dramatic example of what can happen when you mess with Mother Nature. -

War of the Currents

An Electric Battle A WebQuest for War of the Currents Introduction At the turn of the twentieth century, the War of the Currents had a clear winner—Tesla and his alternating current. However, direct current survived into the twenty-first century. As recently as 2007, some parts of Manhattan were finally converted to alternating current. The transition from direct current to alternating current begin in the late 1920s but took decades, in part, because the foundation of New York City’s energy grid was build by Edison’s company. Task Your task is to research the everyday devices credited to Edison and Tesla. You will compare these inventor’s influences by creating a script for a 5-min mock “debate” between Edison and Tesla in which they debate their influences on today’s and future technology. Process Use the resources listed in the Resources section to begin your research. The Web sites listed are good starting points, but further Internet research will be necessary. Record your answers to the following questions. 1. What was the relationship between Tesla and Edison prior to the War of the Currents? 2. Both Tesla and Edison were prolific inventors. If the two were competing to obtain the most number of patents filed, who wins and by what margin? 3. Did any of Tesla’s or Edison’s inventions build upon one another or work together to bring about new technology? 4. Could direct current make a comeback? Explain your answer. Write a Script Write a script for a 5-min mock debate between Edison and Tesla, in which each tries to convince the audience that he was the more influential inventor. -

War of Currents

War of Currents In the War of Currents era (sometimes, War of the Currents or Battle of Currents) in the late 1880s, George Westinghouse and Thomas Edison became adversaries due to Edison's promotion of direct current (DC) for electric power distribution over alternating current (AC). Edison's direct-current system generated and distributed electric power at the same voltage as used by the customer's lamps and motors. This meant that the current in transmission was relatively large, and so heavy conductors were required and transmission distances were limited, to about a mile (kilometre); otherwise transmission losses would make the system uneconomical. At the time, no method was practical for changing voltages of DC power. The invention of an efficient transformer allowed high voltage to be used for AC transmission. An AC generating plant could then serve customers at a great distance (tens to hundreds of miles), or could serve more customers within its economical transmission distance. The fewer much larger plants needed for AC would achieve an economy of scale that would lower costs further. The invention of a practical AC motor increased the usefulness of alternating current for powering machinery. Edison's company had invested heavily in DC technology and was vigorously defending its DC based patents. George Westinghouse saw AC as a way to get into the business with his own patented competing system and set up the Westinghouse Electric Company to design and build it. The Westinghouse company also purchased the patents for alternating current devices from inventors in Europe and licensed patents from Nikola Tesla. -

Tor.Com, Which Averages 1 Million Unique Visitors and 3 Million Pageviews Per Month, with

TORDOTCOM JULY 2021 A Psalm for the Wild-Built Becky Chambers Just when the world needs it comes a story of kindness and hope from one of the masters of Hopepunk Hugo Award-winner Becky Chambers's delightful new series gives us hope for the future. It's been centuries since the robots of Panga gained self-awareness and laid down their tools; centuries since they wandered, en masse, into the wilderness, never to be seen again; centuries since they faded into myth and urban legend. One day, the life of a tea monk is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot cannot go back until the question of "what do people need?" is answered. FICTION / SCIENCE FICTION / ACTION & ADVENTURE But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. Tordotcom | 7/13/2021 They're going to need to ask it a lot. 9781250236210 | $20.99 / $28.99 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 160 pages | Carton Qty: 28 8 in H | 5 in W Becky Chambers's new series asks: in a world where people have what they Other Available Formats: want, does having more matter? Ebook ISBN: 9781250236227 Audio ISBN: 9781250807748 PRAISE "This was an optimistic vision of a lush, beautiful world that came back from the brink of disaster. Exploring it with the two main characters was a fun and MARKETING -Long-term support for Hugo Award fascinating experience.” —Martha Wells winner Becky Chambers’ Monk & Robot series, including consumer & industry mailings & advertising targeting existing "I'm the world's biggest fan of odd couple buddy road trips in science fiction, and fans & readers of hopeful science fiction this odd couple buddy road trip is a delight: funny, thoughtful, touching, sweet, and one of the most humane books I've read in a long time. -

Praise for Ninefox Gambit

Praise for Ninefox Gambit ‘Beautiful, brutal and full of the kind of off-hand inventiveness that the best SF trades in, Ninefox Gambit is an effortlessly accomplished SF novel. Yoon Ha Lee has arrived in spectacular fashion.’ – Alastair Reynolds ‘I love Yoon’s work! Ninefox Gambit is solidly and satisfyingly full of battles and political intrigue, in a beautifully built far-future that manages to be human and alien at the same time. It should be a treat for readers already familiar with Yoon’s excellent short fiction, and an extra treat for readers finding Yoon’s work for the first time.’ – Ann Leckie ‘Starship Troopers meets Apocalypse Now – and they’ve put Kurtz in charge... Mind-blistering military space opera, but with a density of ideas and strangeness that recalls the works of Hannu Rajaniemi, even Cordwainer Smith. An unmissable debut.’ – Stephen Baxter ‘A dizzying composite of military space opera and sheer poetry. Every word, name and concept in Lee’s unique world is imbued with a sense of wonder.’ – Hannu Rajaniemi ‘A striking space opera by a bright new talent.’ – Elizabeth Bear ‘For sixteen years Yoon Ha Lee has been the shadow general of science fiction, the calculating tactician behind victory after victory. Now he launches his great manoeuvre. Origami elegant, fox-sly, defiantly and ferociously new, this book will burn your brain. Axiomatically brilliant. Heretically good.’ – Seth Dickinson ‘A high-octane ride through an endlessly inventive world, where calendars are weapons of war and dead soldiers can assist the living. Bold, fearlessly innovative and just a bit brutal, this is a book that deserves to be on every awards list.’ – Aliette de Bodard ‘Daring, original and compulsive. -

The Last Days of Night

FEATURE CLE: THE LAST DAYS OF NIGHT CLE Credit: 1.0 Thursday, June 14, 2018 1:25 p.m. - 2:25 p.m. Heritage East and Center Lexington Convention Center Lexington, Kentucky A NOTE CONCERNING THE PROGRAM MATERIALS The materials included in this Kentucky Bar Association Continuing Legal Education handbook are intended to provide current and accurate information about the subject matter covered. No representation or warranty is made concerning the application of the legal or other principles discussed by the instructors to any specific fact situation, nor is any prediction made concerning how any particular judge or jury will interpret or apply such principles. The proper interpretation or application of the principles discussed is a matter for the considered judgment of the individual legal practitioner. The faculty and staff of this Kentucky Bar Association CLE program disclaim liability therefore. Attorneys using these materials, or information otherwise conveyed during the program, in dealing with a specific legal matter have a duty to research original and current sources of authority. Printed by: Evolution Creative Solutions 7107 Shona Drive Cincinnati, Ohio 45237 Kentucky Bar Association TABLE OF CONTENTS The Presenter .................................................................................................................. i The War of the Currents: Examining the History Behind The Last Days of Night .................................................................................................... 1 AC/DC: The Two Currents -

A Large Crowd Gathers for the Deceased Jeff Elliot's Encore

A Large Crowd Gathers For the Deceased Jeff Elliot’s Encore Performance It was a pretty big story that Jeff Elliot had come back from the dead. That might sound like an understatement, what with the general lack of real life zombies out there. But he wasn’t a zombie. He had just come back from the dead, at least for a little while. As it turned out, it was a short second run for him, though there were certainly enough witnesses to prove he had been around for a little while. Obviously when the world found out, this strange little case became very big. The greatest scientific minds swept through St. John’s to try to prove this all actually happened, religious zealots declared the event a sure sign of the apocalypse, and a new crop of hotlines surfaced claiming you too could contact your loved one for a short time through them ($5.99 a minute, other long distance charges may apply). But this story is not about the fallout. This story is about that day he returned, and what he did with that little bit of extra time he had somehow staked out for himself. See, Jeff wasn’t a big deal at all prior to his death – he was a Newfoundland based musician who played fairly idiosyncratically and generally mixed with the blur that is the St. John’s music scene. Before he died at age 28, he could regularly be seen on “the deck,” near bars like CBTGs and Distortion and The Bull and Barrel, or smoking outside The Ship between sets, or fighting with Ron Hynes down at The Rose and Thistle. -

Fantasy Magazine, Issue 60 (People of Colo(U)R Destroy Fantasy

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 60, December 2016 People of Colo(u)r Destroy Fantasy! Special Issue FROM THE EDITORS Preface Wendy N. Wagner People of Colo(u)r Editorial Roundtable POC Destroy Fantasy! Editors ORIGINAL SHORT FICTION edited by Daniel José Older Black, Their Regalia Darcie Little Badger (illustrated by Emily Osborne) The Rock in the Water Thoraiya Dyer The Things My Mother Left Me P. Djèlí Clark (illustrated by Reimena Yee) Red Dirt Witch N.K. Jemisin REPRINT SHORT FICTION selected by Amal El-Mohtar Eyes of Carven Emerald Shweta Narayan gezhizhwazh Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (illustrated by Ana Bracic) Walkdog Sofia Samatar Name Calling Celeste Rita Baker NONFICTION edited by Tobias S. Buckell Learning to Dream in Color Justina Ireland Give Us Back Our Fucking Gods Ibi Zoboi Saving Fantasy Karen Lord We Are More Than Our Skin John Chu Crying Wolf Chinelo Onwualu You Forgot to Invite the Soucouyant Brandon O’Brien Still We Write Erin Roberts Artists’ Gallery Reimena Yee, Emily Osborne, Ana Bracic AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS edited by Arley Sorg Darcie Little Badger Thoraiya Dyer P. Djèlí Clark N.K. Jemisin Shweta Narayan Leanne Betasamosake Simpson Sofia Samatar Celeste Rita Baker MISCELLANY Subscriptions & Ebooks Special Issue Staff © 2016 Fantasy Magazine Cover by Emily Osborne Ebook Design by John Joseph Adams www.fantasy-magazine.com FROM THE EDITORS Preface Wendy N. Wagner | 187 words Welcome to issue sixty of Fantasy Magazine! As some of you may know, Fantasy Magazine ran from 2005 until December 2011, at which point it merged with her sister magazine, Lightspeed. Once a science fiction-only market, since the merger, Lightspeed has been bringing the world four science fiction stories and four fantasy shorts every month. -

Locus Awards Schedule

LOCUS AWARDS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Fonda Lee and Elizabeth Bear. THURSDAY, JUNE 25 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Tobias S. Buckell, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Fran Wilde. FRIDAY, JUNE 26 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Nisi Shawl and Connie Willis. SATURDAY, JUNE 27 12:00 p.m.: “Amal, Cadwell, and Andy in Conversation” panel with Amal El- Mohtar, Cadwell Turnbull, and Andy Duncan. 1:00 p.m.: “Rituals & Rewards” with P. Djèlí Clark, Karen Lord, and Aliette de Bodard. 2:00 p.m.: “Donut Salon” (BYOD) panel with MC Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, and Gary K. Wolfe. 3:00 p.m.: Locus Awards Ceremony with MC Connie Willis and co-presenter Daryl Gregory. PASSWORD-PROTECTED PORTAL TO ACCESS ALL EVENTS: LOCUSMAG.COM/LOCUS-AWARDS-ONLINE-2020/ KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR EMAIL FOR THE PASSWORD AFTER YOU SIGN UP! QUESTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] LOCUS AWARDS TOP-TEN FINALISTS (in order of presentation) ILLUSTRATED AND ART BOOK • The Illustrated World of Tolkien, David Day (Thunder Bay; Pyramid) • Julie Dillon, Daydreamer’s Journey (Julie Dillon) • Ed Emshwiller, Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller, Jesse Pires, ed. (Anthology Editions) • Spectrum 26: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, John Fleskes, ed. (Flesk) • Donato Giancola, Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend (Dark Horse) • Raya Golden, Starport, George R.R. Martin (Bantam) • Fantasy World-Building: A Guide to Developing Mythic Worlds and Legendary Creatures, Mark A. Nelson (Dover) • Tran Nguyen, Ambedo: Tran Nguyen (Flesk) • Yuko Shimizu, The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Oscar Wilde (Beehive) • Bill Sienkiewicz, The Island of Doctor Moreau, H.G. -

From Cyber-Utopia to Cyber-War. Advocacy Coalitions and the Normative Change in Cyberspace

From Cyber-Utopia to Cyber-War. Normative Change in Cyberspace. Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt dem Rat der Fakultät für Sozial- und Verhaltenswissenschaften der Friedrich- Schiller-Universität Jena von Matthias Schulze (M.A.) geboren am 28.03.1986 in Weimar 15.03.2017 1 Gutachter 1. Prof. Dr. Rafael Biermann (Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena) 2. Dr. Myriam Dunn Cavelty (ETH Zürich) 3. Prof. Dr. Georg Ruhrmann (Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08.08.2017 2 Copyright © 2018 by Matthias Schulze. Some Rights reserved. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. 3 Table of Contents Table of Contents 4 Acknowledgement 7 Abstract 10 List of Abbreviations 11 List of Tables and Graphics 13 1. Introduction 15 1.1 Puzzle & Research Question 18 1.2 Literature Review 22 1.3 Contributions of the Study 27 1.4 Case Selection: The United States 30 1.5 Structure and Logic of the Argument 32 2. Explaining Normative Change 38 2.1 Norms and Theories of Normative Change 39 2.1.1 Norm Diffusion and Norm Entrepreneurs 41 2.1.2 Critique of Deontological Norms 42 2.1.3 Critique of Diffusion Models 44 2.2 Paradigms and Norm-Change 47 2.2.1 Discursive Struggles between Paradigms 53 2.2.2 Framing 59 2.2.3 Degrees of Change 63 2.2.4 Explaining Change 67 -

![The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8392/the-best-childrens-books-of-the-year-2020-edition-1158392.webp)

The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 Edition]

Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-14-2020 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2020). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-14-2020 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2020). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2020 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

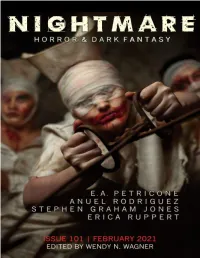

TABLE of CONTENTS Issue 101, February 2021

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 101, February 2021 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: February 2021 FICTION We, the Girls Who Did Not Make It E.A. Petricone The Girl with the Voice Made of Stone Anuel Rodriguez Hairy Legs and All Stephen Graham Jones And Lucy Fell Erica Ruppert NONFICTION The H Word: Horror, Through Colored Lenses Justin C. Key Interview: Hailey Piper Gordon B. White AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS E.A. Petricone Stephen Graham Jones MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks Support Us on Patreon, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard About the Nightmare Team © 2021 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Grace Legault www.nightmare-magazine.com Published by Adamant Press. Editorial: February 2021 Wendy N. Wagner | 1166 words Welcome to issue 101 of Nightmare! I’m Wendy N. Wagner, writing to you in my first- ever editorial, and let me just say: It is an honor and a privilege to be writing to you, our wonderful readers. Thank you so much for joining me on the next leg of our magazine’s terrifying journey. I hope we have a great time together! When it comes to horror, I’m what might be called a “true believer.” Horror novels, video games and movies have gotten me through some of the roughest patches in my life. I’ve escaped unhappiness by diving into the thrills of countless monstrous adventures; I’ve felt my will to live return after a good jump scare—and I’ve found tremendous insight into the human condition in the work of horror creators across all mediums.