6095 ECQ.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X21 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X21 bus time schedule & line map X21 Birmingham - Woodcock Hill via Weoley Castle View In Website Mode The X21 bus line (Birmingham - Woodcock Hill via Weoley Castle) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birmingham: 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM (2) Woodcock Hill: 6:20 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X21 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X21 bus arriving. Direction: Birmingham X21 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Birmingham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:59 AM - 10:54 PM Monday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Shenley Fields Drive, Woodcock Hill Tuesday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Bartley Drive, Woodcock Hill Wednesday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Cromwell Lane, Bangham Pit Thursday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Moors Lane, Birmingham Friday 5:11 AM - 11:44 PM Moors Lane, Bangham Pit Hillwood Road, Birmingham Saturday 5:10 AM - 11:44 PM Woodcock Lane, Bangham Pit Draycott Drive, Bangham Pit Long Nuke Road, Birmingham X21 bus Info Direction: Birmingham Shenley Academy, Woodcock Hill Stops: 42 Long Nuke Road, Birmingham Trip Duration: 39 min Line Summary: Shenley Fields Drive, Woodcock Hill, Fulbrook Grove, Woodcock Hill Bartley Drive, Woodcock Hill, Cromwell Lane, Somerford Road, Birmingham Bangham Pit, Moors Lane, Bangham Pit, Woodcock Lane, Bangham Pit, Draycott Drive, Bangham Pit, Marston Rd, Woodcock Hill Shenley Academy, Woodcock Hill, Fulbrook Grove, Austrey Grove, Birmingham Woodcock Hill, Marston Rd, Woodcock Hill, Quarry Rd, Weoley Castle, Ruckley Rd, Weoley Castle, Quarry Rd, Weoley Castle Gregory Ave, Weoley -

Weoley Castle

Weoley Castle Weoley Castle is a cherished community site. The ruins are over seven hundred years old and are the remains of a moated medieval manor house that once stood there. It was once protected by its walls but now it is protected by the Castle Keepers. Come rain or shine volunteer Castle Keepers care for the site and do everything from practical maintenance to research and running activities for the local community to enjoy. Thanks to the Castle Keepers visitors can enjoy a whole array of events; making crafts in the community classroom, having a guided tour of the site, and even seeing history brought to life with the annual Living History day. The Castle Keepers have transformed the site and the community’s understanding of Weoley Castle, they are hugely valued by Birmingham Museums Trust. However, volunteering is a two way street and there has to be something in it for the team too. Jo, one of our Castle Keepers says “I enjoy the company, the variety of things that we do and the fact that we are out in the open and doing something valuable” and they certainly are. The research they are doing on mason marks will help historians for years to come, the community benefits hugely from having such a great range of family activities on their door step, and visitors from far and wide can benefit from the impact of the maintenance work as the ruins can be viewed from a viewing platform which is open every day. Volunteer castle keepers at Weoley Castle © Alex Nicholson‐Evans, Birmingham Museums Trust If you require an alternative accessible version of this document (for instance in audio, Braille or large print) please contact our Customer Services Department: Telephone: 0370 333 1181 Fax: 01793 414926 Textphone: 0800 015 0516 E-mail: [email protected] . -

Strategic Needs Assessment

West Midlands Violence Reduction Unit STRATEGIC NEEDS ASSESSMENT APRIL 2021 westmidlands-vru.org @WestMidsVRU 1 VRU STRATEGIC NEEDS ASSESSMENT CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................3 Violence has been rising in the West Midlands for several years, a trend - sadly - that has been seen across 2. Introduction and Aims .............................................................................................................................4 much of England & Wales. Serious violence, such as knife crime, has a disproportionately adverse impact on some of our most vulnerable 3. Scope and Approach ................................................................................................................................5 people and communities. All too often, it causes great trauma and costs lives, too often young ones. 4. Economic, Social and Cultural Context ...............................................................................................6 In the space of five years, knife crime has more than doubled in the West Midlands, from 1,558 incidents in the year to March 2015, to more than 3,400 in the year to March 2020, according to the Office for National Statistics. 5. The National Picture – Rising Violence ...............................................................................................8 Violence Reduction Units were set up to help prevent this rise in serious violence -

Sutton Coldfield Four Oaks Childrens Centre Kittoe Road, Birmingham

Where to get Healthy Start Vitamins (Vitamin D Campaign) in the Birmingham Area Sutton Coldfield Four Oaks Childrens Centre Kittoe Road, Birmingham, B74 4RX 0121 323 1121 / New Hall Children Centre Langley Hall Drive, Birmingham, B75 7NQ 012107584233492 464 5170 Bush Babies Childrens Centre 1 Tudor Close, Sutton Coldfield, Birmingham, B73 6SX 0121 354 9230 James Preston Health Centre 61 Holland Road, Birmingham, B75 1RL 0121 465 5258 Boots Pharmacy 80-82 Boldmere Road, Birmingham, B73 5TJ 0121 354 2121 Stockland Green / Erdington Erdington Hall Childrens Centre Ryland Road, Birmingham, B24 8JJ 0121 464 3122 Featherstone' Chidren's Centre & Nusery School 29 Highcroft Road, Birmingham, B23 6AU 0121 675 3408 Lakeside Childrens Centre Lakes Road, Erdington, Birmingham, B23 7UH 0121 386 6150 Erdington Medical Centre 103 Wood End Road , Birmingham, B24 8NT 0121 373 0085 Dove Primary Care Centre 60 Dovedale Road, Birmingham, B23 5DD 0121 465 5715 Eaton Wood Medical Centre 1128 Tyburn Road, Birmingham, B24 0SY 0121 465 2820 Stockland Green Primary Care Centre 192 Reservoir Road, Birmingham, B23 6DJ 0121 465 2403 Boots Pharmacy 87 High Street, Erdington, Birmingham, B23 6SA 0121 373 0145 Boots Pharmacy Fort Shopping Park ,Unit 8, Birmingham, B24 9FP 0121 382 9868 Osborne Children's Centre Station Road, Erdington, Birmingham, B23 6UB 0121 675 1123 High Street Pharmacy 36 High Street, Birmingham, B23 6RH 0121 377 7274 Barney's Children Centre Spring Lane, Erdington, Birmingham, B24 6BY 0121 464 8397 Jhoots Pharmacy 70 Station Road, Bimringham, B23 -

Birmingham Museums Trust Annual Report 2019-20

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 / 20 REFLECTING BIRMINGHAM TO THE WORLD, AND THE WORLD TO BIRMINGHAM Birmingham Museums Trust is an independent educational charity formed in 2012. It cares for Birmingham’s internationally important collection of one million objects which are stored and displayed in nine unique venues including six listed buildings and one scheduled monument. Birmingham Museums Trust is a company limited by guarantee. Registered charity number: 1147014 CONTENTS AUDIENCES COLLECTIONS 9 Children and young people 26 Acquisitions Case study MiniBrum co-production with Case study Waistcoat worn by Gillian Smith Henley Montessori School 27 Loans 10 Community engagement Case study Victorian radicals Case studies CreateSpace, Charity Awards 28 Collections Care 2019 – Overall Award for Excellence Case study Staffordshire Hoard monograph 11 Volunteers 29 Curatorial Case study Works on paper: digitisation Case studies Birmingham revolutions – power volunteers to the people and Dressed to the nines 12 Marketing and audience development Case study Royal Foundation visit to MAKING IT HAPPEN MiniBrum 13 Digital audiences 30 Workforce development Case study Planetarium upgrade 31 Development 15 Supporters Case study Corporate membership scheme VENUES TRADING 17 Aston Hall 32 Retail Case study The haunted house Case study All about Brum 18 Blakesley Hall 33 Food and beverage Case study Herb Garden Café Case study Signal Box refurbishment 19 Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery 33 Conference and banqueting Case study Home of Metal presents Black Case study -

West Midlands History

Friends of the Centre for West Midlands History Newsletter Issue 3 February 2010 Sharing the Past with the Future Black Country History Day 2009 by Judith Watkin The fourth Black Country History Day, Ward, had influenced the development of by Benjamin Molineux, an ironmaster, in which was organised in partnership with the Industrial Revolution in the West of the the early 18th century. After the Exhibition the University of Birmingham and the Black Country in the late 18th Century of Staffordshire Arts and Industry was held Black Country Society through his building of canals and the there in 1869, the gardens became a public (www.blackcountrysociety.co.uk), took introduction of Enclosure Bills which pleasure ground until later being used place on 24th October 2009. paved the way for the exploitation of the partly for the building of the Molineux land and particularly its minerals, thus Football Ground, home of Wolverhampton This popular day school was chaired by greatly increasing his family's wealth. Wanderers. David showed how the Malcolm Dick and opened with Paul building and its interior features had been Belford, Head of Archaeology at the Dr Catherine Round, an Outreach Officer restored from dereliction to become a state Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust, for Broadfield House Glass Museum, of the art repository and centre for considering the early history of opened the afternoon session by charting Wolverhampton's Archive Service. Wednesbury Forge as it had been revealed the history of glassmaking and the during the dig he had been commissioned migration of glassworkers across Europe to The Black Country Society was founded in to carry out ahead of the redevelopment of the Stourbridge area. -

Northfield << Click Here >> Longbridge Kings Norton Weoley

Northfield Constituency Policing Teams May 2019 Newsletter Kings Norton - Northfield - Weoley Castle - Longbr idge Welcome to our May 2019 Newsletter from the Northfield Constituency Policing Teams. In addition to the crime updates we regularly send out through wmnow we also want to keep you updated with some of the other positive work that your local policing teams in the Kings Norton, Longbridge, Weoley and Northfield have been doing during May. In May, we welcomed Sgt Sharon Brain to the Constituency. Sgt Brain replaces Sgt Tandy as the Kings Norton Policing Supervisor following Sgt Tandy’s move to a new role. We wish both of them the best of luck in their new roles. Crime Statistics (Data from Police.co.uk) Feb 2019 March 2019 Burglary Kings Norton 36 38 Longbridge 13 19 Weoley Castle 32 38 Northfield 16 15 Vehicle Crime Kings Norton 24 20 Longbridge 8 20 Weoley Castle 24 20 Northfield 22 25 Robbery Kings Norton 12 13 Longbridge 8 8 Weoley Castle 4 9 Northfield 5 6 ALL Recorded Crime Kings Norton 226 233 Longbridge 180 288 Weoley Castle 210 277 Northfield 217 234 During May, your local neighbourhood policing teams have continued to carry out a range of pro-active activities and initiatives aimed at reducing crime and the fear of crime in the local area. Officers have continued to target the people who are causing the most harm to our communities. Reducing burglaries is still one of our priorities, The impact of burglary isn’t just financial; it can also have a significant impact on your emotional well-being and sense of security. -

Longbridge Centres Study Good Morning / Afternoon / Evening. I Am

Job No. 220906 Longbridge Centres Study Good morning / afternoon / evening. I am ... calling from NEMS Market Research, we are conducting a survey in your area today, investigating how local people would like to see local shops and services improved. Would you be kind enough to take part in this survey – the questions will only take a few minutes of your time ? QA Are you the person responsible or partly responsible for most of your household's shopping? 1 Yes 2No IF ‘YES’ – CONTINUE INTERVIEW. IF ‘NO’ – ASK - COULD I SPEAK TO THE PERSON WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR MOST OF THE SHOPPING? IF NOT AVAILABLE THANK AND CLOSE INTERVIEW Q01 At which food store did you last do your household’s main food shopping ? DO NOT READ OUT. ONE ANSWER ONLY. IF 'OTHER' PLEASE SPECIFY EXACTLY STORE NAME AND LOCATION Named Stores 01 Aldi, Cape Hill, Smethwick 02 Aldi, Selly Oak 03 Aldi, Sparkbrook 04 Asda, Bromsgrove 05 Asda, Merry Hill 06 Asda, Oldbury 07 Asda, Small Heath / Hay Mills 08 Co-op, Maypole 09 Co-op, Rubery 10 Co-op Extra, Stirchley 11 Co-op, West Heath 12 Iceland, Bearwood 13 Iceland, Bromsgrove 14 Iceland, Harborne 15 Iceland, Halesowen 16 Iceland, Kings Heath 17 Iceland, Northfield 18 Iceland, Shirley 19 Kwik Save, Stirchley 20 Lidl, Balsall Heath 21 Lidl, Dudley Road 22 Lidl, Silver Street, Kings Heath 23 Marks & Spencer, Harborne 24 Morrisons, Birmingham Great Park 25 Morrisons, Bromsgrove 26 Morrisons, Redditch 27 Morrisons, Shirley (Stratford Road) 28 Morrisons, Small Heath 29 Netto, Warley 30 Sainsburys, Blackheath, Rowley Regis 31 Sainsburys, -

Birmingham City Council

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL PLANNING COMMITTEE Thursday, 12 October 2017 at 1100 hours in Committee Rooms 3 and 4, Council House, Birmingham P U B L I C A G E N D A – D E C I S I O N S 1 NOTICE OF RECORDING/WEBCAST Noted. 2 CHAIR'S ANNOUNCEMENTS See Minutes. 3 APOLOGIES Councillors Azim and K Jenkins. 4 MINUTES Noted the public part of the Minutes of the last meeting. 5 MATTERS ARISING See Minutes. 6 NOTIFICATION BY MEMBERS OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS THAT THEY CONSIDER SHOULD BE DETERMINED BY COMMITTEE Notifications from Members – See Minutes. 7 PETITION(S) None. PLANNING APPLICATIONS IN RESPECT OF THE NORTH WEST AREA 8 FORMER HARDY SPICER SPORTS GROUND AND LAND BETWEEN SIGNAL HAYES ROAD AND WEAVER AVENUE, WALMLEY, SUTTON COLDFIELD – 2017/06231/PA The Committee did not endorse the Deed of Variation to the existing S106 legal agreement. 9 LAND BOUNDED BY VENTNOR AVENUE/MELBOURNE AVENUE/ WHEELER STREET (FORMER WHEELER TAVERN), NEWTOWN – 2017/07183/PA Agreed recommendations. 10 81-89 WATER ORTON LANE, LAND BETWEEN, SUTTON COLDFIELD – 2017/06759/PA Agreed recommendations. 11 378 BOLDMERE ROAD, SUTTON COLDFIELD – 2017/05130/PA Agreed recommendations subject to amendments. 12 2 GROUNDS DRIVE, LAND ADJACENT, SUTTON COLDFIELD – 2017/06546/PA Agreed recommendations. PLANNING APPLICATIONS IN RESPECT OF THE SOUTH AREA 13 17A NORFOLK ROAD, EDGBASTON – 2017/06473/PA Agreed recommendations. 14 BURNEL ROAD, WEOLEY CASTLE – 2017/05529/PA Agreed recommendations. 15 UNITS 7-8 SELLY OAK INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, ELLIOTT ROAD, SELLY OAK – 2017/07286/PA Agreed recommendations. 16 93 ALCESTER ROAD, MOSELEY – 2017/07118/PA Agreed recommendations. -

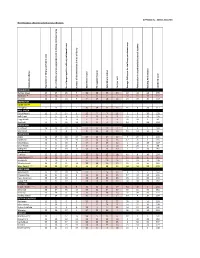

Libraries Ranked on Key Indicators C Ommun Ity Lib Ra Ry P O Pula Tio Nof Libr

APPENDIX 3a - NEEDS ANALYSIS Need Analysis: Libraries ranked on key indicators Community Library area catchment library of Population area catchment library in 0-19 people young and children of No. area catchment library in 65+ aged peope of No. Number of libraries within 2 miles of library issued items Total hours) (in usage PC Total visitors library visit per Cost area catchment the library for score IMD Average sessions educational and events in Participation Building Performance score Combined EDGBASTON Bartley Green 29 29 26 9 32 36 35 34 22 16 28 296 Harborne * 11 18 7 19 3 8 11 7 32 11 10 137 Quinton 14 14 10 9 7 19 18 12 25 19 20 167 ERDINGTON Castle Vale ** Erdington 2 4 5 1 10 10 12 21 16 8 28 117 HALL GREEN Balsall Heath 15 9 24 9 12 7 7 11 2 6 20 122 Hall Green 7 5 6 19 4 29 6 8 29 3 20 136 Kings Heath 5 6 4 19 2 11 2 3 28 10 1 91 Sparkhill 4 3 16 19 5 9 4 1 14 7 28 110 HODGE HILL Shard End 26 23 23 19 27 15 19 2 9 5 1 169 Ward End 1 1 8 1 8 12 15 13 11 12 10 92 LADYWOOD Aston 21 15 28 19 29 22 27 22 3 29 1 216 Birchfield 20 16 29 19 22 14 24 33 12 26 1 216 Bloomsbury 33 31 36 9 37 37 37 36 1 32 38 327 Small Heath 3 2 15 9 9 6 3 10 4 25 9 95 Spring Hill 34 34 34 19 31 13 23 29 7 27 10 261 NORTHFIELD Frankley 35 35 33 1 35 33 25 18 10 9 20 254 Kings Norton*** 18 20 14 1 15 28 17 5 24 18 1 161 Northfield 9 10 3 1 6 3 10 16 27 13 10 108 Weoley Castle 16 17 11 19 18 18 13 15 21 23 10 181 West Heath***** 30 32 27 0 24 17 28 20 26 34 38 276 PERRY BARR Handsworth 13 11 20 19 21 2 16 23 8 21 9 163 Kingstanding 24 21 19 9 23 25 21 -

29 Frankley - Northfield - Birmingham City Centre Via Weoley Castle & Harborne

29 Frankley - Northfield - Birmingham City Centre via Weoley Castle & Harborne Monday to Friday from 29th May 2016 Holly Hill New Street - - - - - 0619 - - 0655 - - 0730 0745 - 0818 - 0856 - 0931 - Northfield Lockwood Rd 0504 0531 0554 0608 0622 0631 0645 0656 0707 0718 0733 0746 0801 0817 0834 0857 0912 0930 0945 1000 Weoley Castle Square 0514 0541 0604 0618 0632 0643 0657 0708 0720 0731 0746 0759 0814 0831 0847 0910 0925 0943 0958 1013 California Barnes Hill 0520 0547 0610 0624 0638 0649 0703 0715 0727 0739 0754 0807 0822 0838 0854 0917 0932 0950 1005 1020 Harborne Serpentine Rd 0529 0556 0620 0634 0649 0700 0715 0727 0739 0752 0807 0820 0835 0852 0908 0929 0944 1001 1016 1031 Five Ways Broad Street 0537 0604 0629 0644 0659 0712 0727 0741 0755 0810 0825 0840 0855 0910 0926 0941 0956 1012 1027 1042 City Centre Colmore Circus 0546 0613 0638 0654 0709 0723 0738 0752 0807 0822 0837 0852 0907 0922 0938 0953 1008 1023 1038 1053 Holly Hill New Street 1001 - 1031 - 1101 - 1131 - 1201 - 1231 - 1301 - 1331 - 1401 - 1431 - Northfield Lockwood Rd 1015 1030 1045 1100 1115 1130 1145 1200 1215 1230 1245 1300 1315 1330 1345 1400 1415 1430 1445 1500 Weoley Castle Square 1028 1043 1058 1113 1128 1143 1158 1213 1228 1243 1258 1313 1328 1343 1358 1413 1428 1443 1459 1515 California Barnes Hill 1035 1050 1105 1120 1135 1150 1205 1220 1235 1250 1305 1320 1335 1350 1405 1420 1435 1450 1506 1522 Harborne Serpentine Rd 1046 1101 1116 1131 1146 1201 1216 1231 1246 1301 1316 1331 1346 1401 1416 1431 1446 1501 1518 1534 Five Ways Broad Street 1057 1112 1127 1142 -

General Medical Services (GMS) Contract

FOI GMS Practices 27th November 2018 PRACTICE NAME Name of GP Lead Address1 Address2 Address3 Post Code Tel Frankley Health Centre Dr M Bhardwaj 125 New Street Rednal Birmingham B45 0EU 0121 453 8211 SHAH ZAMAN SURGERY Dr Asad Zaman Castle Vale Primary Care Centre 70 Tangmere Drive, Castle Vale Birmingham B35 7QX 0121 465 1500 Park Medical Centre Dr Jonathan Allcock 691 Coventry Road Small Heath Birmingham B10 0JL 0121 796 4111 GREENRIDGE SURGERY Dr Louise C Lumley 671 Yardley Wood Road Billesley Birmingham B13 0HN 0121 465 8230 West Heath Road Medical Centre Dr A Vora 196 West Heath Road West Heath Birmingham B31 3HB 0121 476 1135 POOLWAY MEDICAL CENTRE Dr Nahmana Khan Church Lane Health Centre 80 Church Lane; Kitts Green Birmingham B33 9EN 0121 785 0795 SWAN MEDICAL CENTRE Dr Barry Tricklebank 4 Willard Rd Yardley Birmingham B25 8AA 0121 706 0337 CHURCH LANE - KHAN Dr Imtiaz Khan 113 Church Lane Stechford Birmingham B33 9EJ 0845 071 1104 KINGSBURY ROAD MEDICAL CENTRE Dr Prem S Jhittay 273 Kingsbury Road Erdington Birmingham B24 8RD 0121 382 7539 HILLCREST SURGERY (twickenham Road) Dr Rupesh Jha 9 Twickenham Road Kingstanding Birmingham B44 0NN 0845 601 6576 HILLCREST SURGERY/ KINGSTANDING SURGERY (Dyas Road Surgery)Dr Rupesh Jha 6 Dyas Road Great Barr Birmingham B44 8SF 0121 373 1885 YARDLEY WOOD HEALTH CENTRE Dr Colin Eagle 401 Highfield Road Yardley Wood Birmingham B14 4DU 0121 474 5186 MOSELEY MEDICAL CENTRE Dr K Somasundara-Rajah 21 Salisbury Road Moseley Birmingham B13 8JS 0121 449 0122 MILLENNIUM MEDICAL CENTRE Dr Janet Wigley