Medical Termination of Pregnancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Locating the Survivor in the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law I

Locating the Survivor in the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law i Locating the Survivorin the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law LAWYERS COLLECTIVE WOMEN’S RIGHTS INITIATIVE Contents Contents v Foreword ix Acknowledgments xi Abbreviations xiii Introduction I. Kinds of Offences and Cases 2 1. Bailable Offence 2 2. Non Bailable Offence 2 3. Cognisable Offences 2 4. Non Cognisable Offences 2 5. Cognisable Offences and Police Responsibility 3 6. Procedure for Trial of Cases 3 II. First Information Report 4 1. Process of Recording Complaint 4 2. Mandatory Reporting under Section 19 of the POCSO Act 4 3. Special Procedure for Children 5 4. Woman Officer to Record Information in Specified Offences 5 5. Special Process for Differently-abled Complainant 6 6. Non Registration of FIR 6 7. Registration of FIR and Territorial Jurisdiction 8 III. Magisterial Response 9 1. Remedy against Police Inaction 10 IV. Investigation 11 1. Steps in Investigation 12 2. Preliminary, Pre-FIR Inquiry by the Police 12 Locating the Survivor in the Indian Criminal Justice System: Decoding the Law v 3. Process of Investigation 13 4. Fair Police Investigation 14 5. Statement and Confessions 14 (i) Examination and statements of witnesses 14 (ii) Confessions to the magistrate 16 (iii) Recording the confession 16 (iv) Statements to the magistrate 16 (v) Statement of woman survivor 17 (vi) Statement of differently abled survivor 17 6. Medical Examination of the Survivor 17 (i) Examination only by consent 17 (ii) Medical examination of a child 17 (iii) Medical examination report 18 (iv) Medical treatment of a survivor 18 7. -

Record of Proceedings SUPREME COURT

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION SUO MOTU WRIT(CRL.) NO.1 OF 2017 IN RE: TO ISSUE CERTAIN GUIDELINES REGARDING INADEQUACIES AND DEFICIENCIES IN CRIMINAL TRIALS O R D E R During the course of hearing of Criminal Appeal No.400/2006 and connected matters, Mr. R. Basant, learned Senior Counsel appearing for the appellants-complainant, pointed out certain common inadequacies and deficiencies in the course of trial adopted by the trial court while disposing of criminal cases. In particular, it was pointed out that though there are beneficial provisions in the Rules of some of the High Courts which ensure that certain documents such as list of witnesses and the list of exhibits/material objects referred to, are annexed to the judgment and order itself of the trial court, these features do not exist in Rules of some other High Courts. Undoubtedly, the judgments and orders of the trial court which have such lists annexed, can be appreciated much better by the appellate courts. Certain other matters were also pointed out by Mr. Basant, learned Senior Counsel for the appellants- complainant, during the course of arguments. He made the 2 following submissions : A. In the course of discussions at the Bar while considering this case, this Court had generally adverted to certain common inadequacies and imperfections that occur in the criminal trials in our country. I venture to suggest that in the interests of better administration of criminal justice and to usher in a certain amount of uniformity, and acceptance of best practices prevailing over various parts of India, this Court may consider issue of certain general guidelines to be followed across the board by all Criminal Courts in the country. -

Supreme Court of India [ It Will Be Appreciated If

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA [ IT WILL BE APPRECIATED IF THE LEARNED ADVOCATES ON RECORD DO NOT SEEK ADJOURNMENT IN THE MATTERS LISTED BEFORE ALL THE COURTS IN THE CAUSE LIST ] DAILY CAUSE LIST FOR DATED : 14-10-2020 Court No. 1 (Hearing Through Video Conferencing) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.S. BOPANNA HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE V. RAMASUBRAMANIAN 14 Diary No. 19651-2020 XVI-A FUTURE GAMING AND HOTEL SERVICES PVT. LTD. AND ANR. ROHINI MUSA Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. {Mention Memo} FOR ADMISSION and IA No.93221/2020-STAY APPLICATION and IA No.93219/2020- PERMISSION TO FILE PETITION (SLP/TP/WP/..) Court No. 4 (Hearing Through Video Conferencing) HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE UDAY UMESH LALIT HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE S. RAVINDRA BHAT HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE HRISHIKESH ROY (TIME : 10:30 AM) 19 Diary No. 16528-2020 II UNION OF INDIA B. KRISHNA PRASAD Versus NAR SINGH MAJHI FOR ADMISSION and I.R. and IA No.82876/2020- CONDONATION OF DELAY IN FILING Court No. 5 (Hearing Through Video Conferencing) HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.M. KHANWILKAR HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE B.R. GAVAI HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE KRISHNA MURARI (TIME : 10:30 AM) 8 W.P.(C) No. 977/2020 X ALL INDIA HAJ UMRAH TOUR ORGANISERS ASSOCIATION MUMBAI GAURAV AGRAWAL Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. FOR ADMISSION and IA No.85737/2020- EXEMPTION FROM FILING AFFIDAVIT and IA No.85736/2020-APPROPRIATE ORDERS/DIRECTIONS 9 W.P.(C) No. 926/2020 PIL-W FEDERAL MOGUL ANAND SEALINGS INDIA LIMITED AAKARSHAN ADITYA Versus UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. -

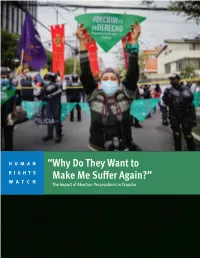

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

In the Chambers of Hon'ble the Chief Justice

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA LIST OF CURATIVE & REVIEW PETITIONS (BY CIRCULATION) IN THE CHAMBERS OF HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE DAILY CAUSE LIST FOR DATED : 16-03-2021 HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.S. BOPANNA HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE V. RAMASUBRAMANIAN (TIME : 1:30 PM) SNo. Case No. Petitioner / Respondent 1001 Diary No. 2361-2021 DIONISIO FRANCISCO TRINIDADE IX Versus NANESHWAR GOPAL FADTE AND ORS. IN SLP(C) No. - 7560/2020, IN SLP(C) No. - 7561/2020, IN SLP(C) No. - 7562/2020, IN SLP(C) No. - 7563/2020, IA No. 12504/2021 - CONDONATION OF DELAY IN FILING REVIEW PETITION IA No. 12506/2021 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT IA No. 12511/2021 - ORAL HEARING IA No. 12517/2021 - PERMISSION TO FILE ADDITIONAL DOCUMENTS/FACTS/ANNEXURES 1002 Diary No. 3949-2021 THE STATE OF SIKKIM XVI-A Versus YOGEN GHATANI AND ORS. IN SMTP(C) No. - 1/2020, IA No. 20923/2021 - CONDONATION OF DELAY IN FILING REVIEW PETITION NEW DELHI 12-03-2021 15:00:28 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SUPREME COURT OF INDIA LIST OF CURATIVE & REVIEW PETITIONS (BY CIRCULATION) IN THE CHAMBERS OF HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE DAILY CAUSE LIST FOR DATED : 16-03-2021 HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE A.S. BOPANNA HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE HRISHIKESH ROY (TIME : 1:35 PM) SNo. Case No. Petitioner / Respondent 1003 R.P.(C) No. 232/2021 in IET BHADDAL SLP(C) No. 7167/2020 IV-B Versus THE STATE OF PUNJAB AND ORS. IN SLP(C) No. -

To Be Published in the Gazette of India, Part 1 Section 2

(TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA, PART 1 SECTION 2) No.K-13011/04/2019-US.I (iv) Government of India Ministry of Law and Justice (Department of Justice) Jaisalmer House, 26, Man Singh Road, NEW DELHI-I 10 011, dated rs" September, 2019. NOTIFICATION In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (2) of Article 124 of the Constitution of India, the President is pleased to appoint Shri Justice Hrishikesh Roy, Chief Justice of the Kerala High Court, to be a Judge of the Supreme Court of India with effect from the date he assumes charge of his office. ~/~'1 (Rajinder Kashyap) Joint Secretary to the Government of India Tel: 23383037 To The Manager, Government of India Press, Minto Road, New Delhi - - - -- --------- - 2 - No. K. 13011/04/2019-US.I (iv) Dated 18.09.2019 Copy to:- 1. Shri Justice Hrishikesh Roy, Chief Justice, Kerala High Court, Kochi. 2. The Secretary to the Governor of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram. 3. The Secretary to the Chief Minister of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram. 4. The Secretary to the Chief Justice, Kerala High Court, Kochi. S. The Chief Secretary, Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram. 6. The Registrar General, Kerala High Court, Kochi. 7. The Accountant General, Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram. 8. The President's Secretariat, (CA.II Section), New Delhi 9 PS to Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister, New Delhi. 10 Registrar (Conf.), % Chief Justice ofIndia, S Krishna Menon Marg, New Delhi. II PS to ML&J/PPS to Secretary (J)/JS(RKK)/DS(ANS)/US.II1S0(Desk) 12. Technical Director, NIC, Department of Justice, with a request to upload on the Website of the Department (www.doj.gov.in). -

Talks with Ramana Maharshi

TALKS WITH SRI RAMANA MAHARSHI Volume One FOREWORD* The “Talks”, first published in three volumes, is now issued a handy one-volume edition. There is no doubt that the present edition will be received by aspirants all over the world with the same veneration and regard that the earlier edition elicited from them. This is not a book to be lightly read and laid aside; it is bound to prove to be an unfailing guide to increasing numbers of pilgrims to the Light Everlasting. We cannot be too grateful to Sri Munagala S. Venkataramiah (now Swami Ramanananda Saraswati) for the record that he kept of the “Talks” covering a period of four years from 1935 to 1939. Those devotees who had the good fortune of seeing Bhagavan Ramana will, on reading these “Talks”, become naturally reminiscent and recall with delight their own mental record of the words of the Master. Despite the fact that the great Sage of Arunachala taught for the most part through silence, he did instruct through speech also, and that too lucidly without baffling and beclouding the minds of his listeners. One would wish that every word that he uttered had been preserved for posterity. But we have to be thankful for what little of the utterances has been put on record. These “Talks” will be found to throw light on the “Writings” of the Master; and probably it is best to study them along with the “Writings”, translations of which are available. Sri Ramana’s teachings were not given in general. In fact, the Sage had no use for “lectures” or “discourses”. -

Ecommittee Newsletter November 2020

November 2020 Newsletter e-Committee, Supreme Court of India NORTH EAST GETS THE FIRST VIRTUAL COURT AT ASSAM. The 1st Virtual Court of North-East august presence of Hon’ble Dr India was inaugurated for the State Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Judge – of Assam, on 12th November 2020, cum- Chairperson, e-Committee, by Hon’ble Chief Minister of Assam, Supreme Court of India, Hon’ble Mr Sri Sarbananda Sonowal in the Justice Hrishikesh Roy, Judge, e-Committee Newsletter, November 2020 2 Supreme Court of India, Hon’ble Mr thus freeing up judicial manpower for Justice N. Kotiswar Singh, Chief essential judicial functions. Justice (Acting), Gauhati High Court, In this regard, Gauhati High Court, Hon’ble Chief Justices & Judges of under the aegis of the e-Committee, Various High Courts. Mr Barun Mitra the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India, Secretary, Department of Justice, Mr has taken up the project of the Justice R.C. Chavan, Vice- setting of Virtual Courts for traffic Chairperson, e-Committee, violations. Gauhati High Court has Supreme Court of India, Dr Neeta taken a proactive role in Verma, Director General, National implementing e-Challan by the State Informatics Centre, Government of Police for enabling the Virtual India, CPCs of Various High Courts, Courts. District Administrations, Police The High Court’s e-Courts Division Officials under the Jurisdiction of the made a presentation on the Gauhati High Court joined the implemented e-Challans for the function virtually. Police Authorities and the ease of Virtual courts provide a convenient services offered by the Virtual Courts option for citizens to pay traffic fines for the Citizens. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

SUPREME COURT of INDIA Girish Sharma Vs. the State Of

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Girish Sharma Vs. The State of Chhattisgarh Crl.A.No.939-940 of 2017 (Adarsh Kumar Goel and Uday Umesh Lalit,JJ.,) 23.08.2017 ORDER 1. On 12th February, 2015, FIR No.9/2015 was registered by the Anti-Corruption Bureau and Economic Offences Wing under the provisions of Indian Penal Code and Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988. The allegation was that huge amount was recovered from possession of accused which was as a of corruption. The FIR was against 27 persons but after investigation chargesheet was filed against 16 persons. The persons against whom the chargesheet was filed included senior officers of the Chhattisgarh State Civil Supplies Corporation. 2. During investigation, statements of three of the accused mentioned in the FIR, namely, Girish Sharma, Arvind Singh Dhruv and Jeet Ram Yadav, who are appellants before us, were recorded under Sections 161 and 164 Cr.P.C. They were not arrayed as accused but were cited as witnesses in the chargesheet. After the court took cognizance against the accused named in the chargesheet, some of the accused made applications under Section 193/319 Cr.P.C. to summon the above three persons, Girish Sharma, Arvind Singh Dhruv and Jeet Ram Yadav as accused. 3. The trial court rejected the said applications but the matter was carried in revision before the High Court and the High Court allowed the summoning. The reason given by the High Court in the order of summoning is that procedure under Section 306 Cr.P.C. was not followed which was the only procedure available under the Criminal Procedure Code to make an accused a witness, after grant of pardon with Court’s permission. -

Panchdasi.(Gurmatvee

COMMENTARY ON THE PANCHADASI SWAMI KRISHNANANDA The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India Website: swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Tattva Viveka – Discrimination of Reality Discourse 1: Verses 1-5 ........................................................................ 8 Discourse 2: Verses 6-13 .................................................................... 18 Discourse 3: Verses 14-27 .................................................................. 33 Discourse 4: Verses 28-43 .................................................................. 46 Discourse 5: Verses 44-55 .................................................................. 63 Discourse 6: Verses 54-65 .................................................................. 79 Chapter 2: Pancha Mahabhuta Viveka – Discrimination of the Elements Discourse 7: Verses 1-18 ................................................................... 92 Discourse 8: Verses 19-34 ..............................................................107 Discourse 9: Verses 33-52 ..............................................................121 Discourse 10: Verses 53-66 ..............................................................136 Discourse 11: Verses 60-77 .............................................................151 Discourse 12: Verses 78-99 ..............................................................164 Discourse 13: Verses 100-109 ......................................................177 -

View Entire Book

Orissa Review * June - 2006 A Cult to Salvage Mankind Sarat Chandra The cosmic and terrestrial : both realities are The Hindu inclusiveness is nowhere as reflected in the Jagannath cult of Orissa. The evident as in the rituals of Lord Jagannath. Even cosmic reality of the undying spirit which romance is not excluded in the deity's schedule: abides, endures and sustains; the cosmic reality Once in a week the God is closeted with his of birth and death, as well as the beauty and consort Laksmi (in the ritual Ekanta). The refinement of the terrestrial world are mirrored Sayana Devata golden sculpture used in the in this all-inclusive mid-night ritual after the religious practice. "The Bada Singhara Dhupa, is visible and invisible both not only suggestive but worlds meet in man", even explicit. sang the British poet T.S.Eliot in the Four Over a year Lord Quartets. We may say Jagannath, like human that the Jagannath cult is beings, is engaged in designed to reflect both multification activities. the visible, this-worldly On one occasion realities as well as the (Banabhoji Besha) He cosmic phenomena. sets out on a picnic trip, Hence, the cult reflects a to an idyllic forest land, life style of a god who has which is suggestive of the numerous human God's love for natural attributes. beauty. On the other occasions (seven times in a year), the Lord goes This makes the God and the cult unique. for hunting expeditions. During the summer Several traits characterize the God: the everyday rituals of bathing, brushing of teeth, he goes for boat rides for twenty-one days dressing-up and partaking of food materials.