The Development of Hand and Foot in Hominoidea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

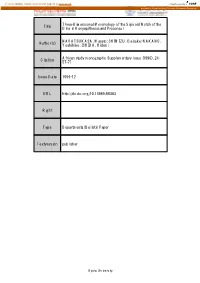

Title Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of the Title Ulna in Kenyapithecus and Proconsul NAKATSUKASA, Masato; SHIMIZU, Daisuke; NAKANO, Author(s) Yoshihiko; ISHIDA, Hidemi African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1996), 24: Citation 57-71 Issue Date 1996-12 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68383 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 24: 57-71, December 1996 57 THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID NOTCH OF THE ULNA IN KENYAPITHECUS AND PROCONSUL Masato Nakatsukasa Daisuke Shimizu Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Yoshihiko Nakano Department of Biological Anthropology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Osaka University Hidemi Ishida Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University ABSTRACT The three-dimensional (3-D) morphology of the sigmoid notch was examined in Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, and several living anthropoids by using an automatic 3-D digitizer. It was revealed that Kenyapithecus and Proconsul exhibit a very similar morphology of the dis tal region of the sigmoid notch; including the absence of a median keel and a downward sloped coronoid process. In addition, the proxilnal region of the sigmoid notch is curved more acutely relative to the distal region in Proconsul. This morphological complex is unique and not found in the examined living primates. The benefits of 3-D morphometries are discussed. Key Words: Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, sigmoid notch, three-dimensional morphometrics, ulna. INTRODUCTION Recently, automatic three-dimensional (3-0) digitizers have become more fre quently to be used for biometrics. -

Glaciation (Oakley, 1950). Variations in the Proposed Beginning Dates

EVOLUTION OF THE HUMAN HAND AMD THE GREAT HAND-AXE TRADITION Grover S. Krantz The hand-axe is both the earliest and the longest persisting of standar- dized stone tools. They present a continuous history of one tool type from the first to the third interglacial periods, a span.of at least 200,000 years and perhaps as many as half a million. Equally remarkable is their geographical range which covers all of Africa, western Europe and southern Asia--fully half of-the then habitable Old Vorld. Aside from differences in the local stone that was utilized, hand-axes from this whole area are constructed on the same plan and show no clear regional typology. Other tool types occur with hand-axes: utilized flakes are found at all levels, and in the later half of the sequence there-are cleavers, ovates, trimmed flakes and spherical stone balls. Throughout the sequence, however, the basic design of the hand-axe continues with its intended formnapparently unchanged. We thus have a continuous record of man's attempts to produce a single type of 'implement over mst of his tool making history. (See Figure 1.) Recent discoveries of fossil man have made it increasingly evident that biological evolution of the human body was also in progress coincident with the development of ancient stone tool types. 'While the exact time of appearance of Homo siens is still in some dispute (see Stewart, 1950 and Oakley., 1957), it is no nowseriously maintained that the earliest tool makers necessarily approximated the modern or even the neanderthal morphologies. -

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 3 MAY THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Leahanne M, Sarlo Functional Anatomy and Allometry in the Shoulder of ENTITLED........................................................ Suspensory Primates IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. BACHELOR OF ARTS LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES 0-1M4 t « w or c o w n w Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1 Dafinibon*..................................................................................................................................... 2 fFunctional m ivw w iiw irwbaola am foriwi irviiiiHbimanual iw 9 jrvafwooaitiona! Vf aai irwbahavlort iiHviw i# in thaahoukter joint complex......................................................................................3 nyvootiua pooioonaiaA^^AlttAAMAl oanainor................................................................................... i4 *4 -TnoOV a awmang.a Ia M AM JI* nwoo—U^AtkA^AA i (snDBDfllluu)/AuMyAlftAlAnAH |At AkJA^AAtlA•wwacwai* |A .............. 4ia i -Tho lar gibbon: KM obate* ]|£.................................................................................15 ANomatry.......................................................................................................................................16 Material* and matooda.....................................................................................................19 -

Why Trot When You Can Walk? an Investigation of the Walk-Trot Transition in the Horse

Why trot when you can walk? An Investigation of the Walk-Trot Transition in the Horse A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Biological Sciences By Devin A. J. Johnsen 2003 SIGNATURE PAGE THESIS: Why trot when you can walk? An investigation of the Walk-Trot Transition in the Horse AUTHOR: Devin A. J. Johnsen DATE SUBMITTED: __________________________________________ Department of Biological Sciences Dr. Donald F. Hoyt __________________________________________ Thesis Committee Chair Biological Sciences Dr. Steven J. Wickler __________________________________________ Animal & Veterinary Sciences Dr. Edward A. Cogger __________________________________________ Animal & Veterinary Sciences Dr. Sepehr Eskandari __________________________________________ Biological Sciences ii Abstract Parameters ranging from energetics to kinematics, from muscle function to ground reaction force, have been theorized as triggers for a variety of terrestrial gait transitions. The walk-trot transition represents a change between gaits governed by very different mechanics, as the walk is modeled by the inverted pendulum, while the trot is modeled by the spring-mass model. A set of five criteria was established in order to determine a parameter as a trigger of the walk-trot transition in the horse. In addition, these mechanical models can provide specific predictions about the change in leg length during the stride. Six horses walked and trotted over a range of speeds on a high-speed treadmill. Stride parameters were measured using accelerometers, while sonomicrometry and electromyography measured muscle function of the vastus lateralis. Kinematics of the coxofemoral, femorotibial, tarsal, and metatarsophalangeal joints as well as leg length were determined using a high-speed (125 Hz) camera. -

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

Linking Gait Dynamics to Mechanical Cost of Legged Locomotion

REVIEW published: 17 October 2018 doi: 10.3389/frobt.2018.00111 Linking Gait Dynamics to Mechanical Cost of Legged Locomotion David V. Lee 1* and Sarah L. Harris 2 1 School of Life Sciences, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, United States, 2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, United States For millenia, legged locomotion has been of central importance to humans for hunting, agriculture, transportation, sport, and warfare. Today, the same principal considerations of locomotor performance and economy apply to legged systems designed to serve, assist, or be worn by humans in urban and natural environments. Energy comes at a premium not only for animals, wherein suitably fast and economical gaits are selected through organic evolution, but also for legged robots that must carry sufficient energy in their batteries. Although a robot’s energy is spent at many levels, from control systems to actuators, we suggest that the mechanical cost of transport is an integral energy expenditure for any legged system—and measuring this cost permits the most direct comparison between gaits of legged animals and robots. Although legged robots have matched or even improved upon total cost of transport of animals, this is typically achieved by choosing extremely slow speeds or by using regenerative mechanisms. Legged robots have not yet reached the low mechanical cost of transport achieved at speeds used by bipedal and quadrupedal animals. Here we consider approaches Edited by: used to analyze gaits and discuss a framework, termed mechanical cost analysis, that Monica A. Daley, can be used to evaluate the economy of legged systems. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Wrist and Ankle Morphology of Hominoids and Lorisids, with Implications for the Evolution of Hominoid Locomotion

Durham E-Theses A comparative analysis of the wrist and ankle morphology of hominoids and lorisids, with implications for the evolution of hominoid locomotion Read, Catriona S. How to cite: Read, Catriona S. (2001) A comparative analysis of the wrist and ankle morphology of hominoids and lorisids, with implications for the evolution of hominoid locomotion, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3775/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 A Comparative Analysis of the Wrist and Ankle Morphology of Hominoids and Lorisids, with Implications for the Evolution of Hominoid Locomotion A Dissertation presented by Catriona S. Read to The Graduate School For the degree of Master of Science m Biological Anthropology Department of Anthropology University of Durham September 2001 The co11yright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Point-Mass Model of Brachiation

The Journal of Experimental Biology 202, 2609–2617 (1999) 2609 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1999 JEB1788 A POINT-MASS MODEL OF GIBBON LOCOMOTION JOHN E. A. BERTRAM1,*, ANDY RUINA2, C. E. CANNON3, YOUNG HUI CHANG4 AND MICHAEL J. COLEMAN5 1College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, USA, 2Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Cornell University, USA, 3Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, USA, 4Department of Integrative Biology, University of California-Berkeley, USA and 5Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, USA *Author for correspondence at Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sciences, 436 Sandels Building, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 10 June; published on WWW 13 September 1999 Summary In brachiation, an animal uses alternating bimanual losses due to inelastic collisions of the animal with the support to move beneath an overhead support. Past support are avoided, either because the collisions occur at brachiation models have been based on the oscillations of zero velocity (continuous-contact brachiation) or by a a simple pendulum over half of a full cycle of oscillation. smooth matching of the circular and parabolic trajectories These models have been unsatisfying because the natural at the point of contact (ricochetal brachiation). This model behavior of gibbons and siamangs appears to be far less predicts that brachiation is possible over a large range restricted than so predicted. Cursorial mammals use an of speeds, handhold spacings and gait frequencies with inverted pendulum-like energy exchange in walking, but (theoretically) no mechanical energy cost. -

Ancestral Facial Morphology of Old World Higher Primates (Anthropoidea/Catarrhini/Miocene/Cranium/Anatomy) BRENDA R

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 88, pp. 5267-5271, June 1991 Evolution Ancestral facial morphology of Old World higher primates (Anthropoidea/Catarrhini/Miocene/cranium/anatomy) BRENDA R. BENEFIT* AND MONTE L. MCCROSSINt *Department of Anthropology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901; and tDepartment of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Communicated by F. Clark Howell, March 11, 1991 ABSTRACT Fossil remains of the cercopithecoid Victoia- (1, 5, 6). Contrasting craniofacial configurations of cercopithe- pithecus recently recovered from middle Miocene deposits of cines and great apes are, in consequence, held to be indepen- Maboko Island (Kenya) provide evidence ofthe cranial anatomy dently derived with regard to the ancestral catarrhine condition of Old World monkeys prior to the evolutionary divergence of (1, 5, 6). This reconstruction has formed the basis of influential the extant subfamilies Colobinae and Cercopithecinae. Victoria- cladistic assessments ofthe phylogenetic relationships between pithecus shares a suite ofcraniofacial features with the Oligocene extant and extinct catarrhines (1, 2). catarrhine Aegyptopithecus and early Miocene hominoid Afro- Reconstructions of the ancestral catarrhine morphotype pithecus. AU three genera manifest supraorbital costae, anteri- are based on commonalities of subordinate morphotypes for orly convergent temporal lines, the absence of a postglabellar Cercopithecoidea and Hominoidea (1, 5, 6). Broadly distrib- fossa, a moderate to long snout, great facial -

Fleagle and Lieberman 2015F.Pdf

15 Major Transformations in the Evolution of Primate Locomotion John G. Fleagle* and Daniel E. Lieberman† Introduction Compared to other mammalian orders, Primates use an extraordinary diversity of locomotor behaviors, which are made possible by a complementary diversity of musculoskeletal adaptations. Primate locomotor repertoires include various kinds of suspension, bipedalism, leaping, and quadrupedalism using multiple pronograde and orthograde postures and employing numerous gaits such as walking, trotting, galloping, and brachiation. In addition to using different locomotor modes, pri- mates regularly climb, leap, run, swing, and more in extremely diverse ways. As one might expect, the expansion of the field of primatology in the 1960s stimulated efforts to make sense of this diversity by classifying the locomotor behavior of living primates and identifying major evolutionary trends in primate locomotion. The most notable and enduring of these efforts were by the British physician and comparative anatomist John Napier (e.g., Napier 1963, 1967b; Napier and Napier 1967; Napier and Walker 1967). Napier’s seminal 1967 paper, “Evolutionary Aspects of Primate Locomotion,” drew on the work of earlier comparative anatomists such as LeGros Clark, Wood Jones, Straus, and Washburn. By synthesizing the anatomy and behavior of extant primates with the primate fossil record, Napier argued that * Department of Anatomical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook University † Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University 257 You are reading copyrighted material published by University of Chicago Press. Unauthorized posting, copying, or distributing of this work except as permitted under U.S. copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. fig. 15.1 Trends in the evolution of primate locomotion. -

SOCIAL BEHAVIOURS of CAPTIVE Hylobates Moloch (PRIMATES: HYLOBATIDAE) in the JAVAN GIBBON RESCUE and REHABILITATION CENTER, GEDE-PANGRANGO NATIONAL PARK, INDONESIA

TAPROBANICA , ISSN 1800-427X. October, 2010. Vol. 02, No. 02: pp. 97-103. © Taprobanica Nature Conservation Society, 146, Kendalanda, Homagama, Sri Lanka. SOCIAL BEHAVIOURS OF CAPTIVE Hylobates moloch (PRIMATES: HYLOBATIDAE) IN THE JAVAN GIBBON RESCUE AND REHABILITATION CENTER, GEDE-PANGRANGO NATIONAL PARK, INDONESIA Sectional Editor: Colin Groves Submitted: 14 February 2011, Accepted: 08 March 2011 Niki K. Amarasinghe1,2 and A. A. Thasun Amarasinghe1,3 1 Taprobanica Nature Conservation Society, 146, Kendalanda, Homagama, Sri Lanka E-mails: 2 [email protected], 3 [email protected] Abstract Hylobates moloch, Silvery Gibbon occure on the Java island (in the western half of Java), Indonesia. This study presents preliminary data on social behaviours for Silvery Gibbon in captivity. All the individuals had an average active period from 6:30 hr to 16:00 hr (total 9.5 hours). Resting behaviour had the highest percentage (57.05% ± 0.45), followed by movement (21.99% ± 0.14), feeding ( 15.73% ± 0.34), courtship (5.16% ± 0.03), calling (2.35% ± 0.02), social behaviours (1.6% ± 0.09), agonistic behaviours (0.37 % ± 0.01), and copulation (0.05% ± 0.01). Gibbons showed two peaks of feeding, from 06:35 to 07:30 and from 14:35 to 15:30. Gibbons in the JGC made two types of calls: male solo and female solo calls. Males had a lower time budget for calling behaviour than females. All the gibbons showed four types of locomotor behaviours: brachiating, climbing, jumping (including ricocheting) and bipedal. The most frequent locomotor behaviour was brachiation type. All individuals in the study groups showed autogrooming. -

Proconsul Africanus: an Examination of Its Anatomy and Evidence for Its

Perspectives Proconsul africanus: lutionists claim P. africanus lived from 19–17 Ma an examination of (though some sources extend the range to 23–14 its anatomy and Ma) with the KNM-RU evidence for its 7290 specimen falling in the middle at 18 million extinction in a post- years old. Flood catastrophe With the scarcity of hominid fossils from sites alleged to be 3 million Matthew Murdock years old, it is unlikely that so many of the delicate In 1948, Dr Mary Leakey found a Proconsul bones, such as distorted skull at Site R106 on Rusinga vertebrae, wrist and ankle Island, Western Kenya. The find was bones, and ‘thousands of a nearly complete cranium, mandi finger bones’ of baby pro ble and full dentition. Because the Figure 1. Left side of P. africanus cranium KNM-RU 7290 consuls, found during later showing crushed and distorted parietal. skull did not resemble any previously excavations would survive found, a new genus was named for six times longer. These KNMRU 7290 is remarkable this individual. Arthur Hopwood of bones are most likely postFlood, and in that it preserves all 32 teeth. The 11 the Natural History Museum (London) only a few thousand years old. dental formula is 2:1:2:3 in both the coined the name ‘Proconsul’ in honour upper and lower jaw. Proconsul has of the circus chimp ‘Consul the Great’, The skull the typical 5-Y pattern of cusps which which had become famous for riding is seen in the lower molars of other a bicycle, and smoking cigarettes.1,2 The distorted cranium possesses hominoids (Figure 2).