Gunmen of the American West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance

1 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid Poster by Tom Beauvais Courtesy Wikipedia Reviewed by Garry Victor Hill Directed by George Roy Hill. Produced by John Foreman. Screenplay by William Goldman. Cinematography by Conrad Hall. Art Direction by Jack Martin Smith & Philip M. Jefferies. Music by Burt Bacharach. Edited by John C. Howard & Richard C. Meyer. Sound George R. Edmondson. Costume designs: Edith Head. Cinematic length: 110 minutes. Distributed by 20TH Century Fox. Companies: Campanile Productions and the Newman–Foreman Company. Cinematic release: October 1969. DVD release 2006 2 disc edition. Check for ratings. Rating 90%. 2 All images are taken from the Public Domain, The Red List, Wikimedia Commons and Wiki derivatives with permission. Written Without Prejudice Cast Paul Newman as Butch Cassidy Robert Redford as the Sundance Kid Katharine Ross as Etta Place Strother Martin as Percy Garris Henry Jones as Bike Salesman Jeff Corey as Sheriff Ray Bledsoe George Furth as Woodcock Cloris Leachman as Agnes Ted Cassidy as Harvey Logan Kenneth Mars as the town marshal Donnelly Rhodes as Macon Timothy Scott as News Carver Jody Gilbert as the Large Woman on the train Don Keefer as a Fireman Charles Dierkop as Flat Nose Curry Pancho Córdova as a Bank Manager Paul Bryar as Card Player No. 1 Sam Elliott as Card Player No. 2 Charles Akins as a Bank Teller Percy Helton as Sweetface Review In the second half of the 1960s westerns about the twilight of the Wild West suddenly became popular, as if both filmmakers and audiences wanted to keep the West within living memory. -

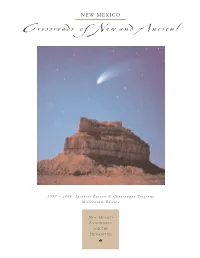

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

Jesse James and His Notorious Gang of Outlaws Staged the World's First Robbery of a Moving Train the Evening of July 21, 1873

In the meantime, the bandits broke into a dropped small detachments of men along handcar house, stole a spike-bar and the route where saddled horses were hammer with which they pried off a fish- waiting. plate connecting two rails and pulled out the The trail of the outlaws was traced into spikes. This was on a curve of the railroad Missouri where they split up and were track west of Adair near the Turkey Creek sheltered by friends. Later the governor of bridge on old U.S. No. 6 Highway (now Missouri offered a $10,000 reward for the County Road G30). capture of Jesse James, dead or alive. A rope was tied on the west end of the On April 3, 1882, the reward reportedly disconnected north rail. The rope was proved too tempting for Bob Ford, a new passed under the south rail and led to a hole member of the James gang, and he shot and Jesse James and his notorious gang of they had cut in the bank in which to hide. killed Jesse in the James home in St. Joseph, outlaws staged the world’s first robbery of a When the train came along, the rail was Missouri. moving train the evening of July 21, 1873, a jerked out of place and the engine plunged A locomotive wheel which bears a plaque mile and a half west of Adair, Iowa. into the ditch and toppled over on its side. with the inscription, “Site of the first train Early in July, the gang had learned that Engineer John Rafferty of Des Moines was robbery in the west, committed by the $75,000 in gold from the Cheyenne region killed, the fireman, Dennis Foley, died of his notorious Jesse James and his gang of was to come through Adair on the recently injuries, and several passengers were outlaws July 21, 1873,” was erected by the built main line of the Chicago, Rock Island & injured. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Anti Trafficking

anti reviewtrafficking GUEST EDITOR DR ANNE GALLAGHER EDITORIAL TEAM CAROLINE ROBINSON REBECCA NAPIER-MOORE ALFIE GORDO The ANTI-TRAFFICKING REVIEW is published by the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW), an alliance of over 100 NGOs worldwide focused on advancing the human rights of migrants and trafficked persons. The Anti-Trafficking Review promotes a human rights-based approach to human trafficking. It explores trafficking in its broader context including gender analyses and intersections with labour and migrant rights. It offers an outlet and space for dialogue between academics, practitioners and advocates seeking to communicate new ideas and findings to those working for and with trafficked persons. The Review is primarily an e-journal, published annually. The journal presents rigorously considered, peer-reviewed material in clear English. Each issue relates to an emerging or overlooked theme in the field of human trafficking. Articles contained in the Review represent the views of the respective authors and not necessarily those of the GAATW network or its members. The editorial team reserves the right to edit all articles before publication. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the publisher. Copyright 2012 by the GLOBAL ALLIANCE AGAINST TRAFFIC IN WOMEN P.O. Box 36, Bangkok Noi Post Office 10700 Bangkok, Thailand Website: www.antitraffickingreview.org ANTI-TRAFFICKING REVIEW Issue 1, June 2012 2 Editorial 10 Measuring the Success of Counter-Trafficking -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

10-17-18 Newsletter.Docx

First RV Trip - Fall 2018 Day 22 Wednesday October 17th .. Great American Adventures Wyatt Earp Vendetta Ride Tombstone, AZ Our location for breakfast this week. They also pack our lunches. Weather 70’s Hello to Family & Friends Sunny Perfect Today starts out on sort of downer but was pretty cool. On the movie ride I carpooled with Doc Crabbe and Omaha. We rod e drag and I remember stating in these newsletters how hilarious it was to drive with them. I even took a video which I may still have. Anyways, Doc Crabbe was also on the Durango/Silverton ride last As a tribute to Doc, Troy September. A week after he returned home from Durango he had led a horse with an a heart attack and passed away. empty saddle and Doc’s Do c was a veteran of about 8-10 rides with GAA. Doc never met a boots placed backwards stra nger. Everyone instantly fell in love with Doc and he always kept in the stirrups, according his cooler in the back of his pickup stocked with beer for anyone to tradition, up and wh o wanted one at the end of the day. The tailgate of his pickup down Allen Street. The wa s a popular gathering spot. Vendetta ride was one Dead Eye Jake, after only joining Doc on the movie ride, felt of Doc’s favorites. impelled to put his image of Doc Crabbe on canvas in oils. The We all followed behind in result is seen below. silence as Tombstone and the Vendetta Riders On this day Doc’s widow, daughter and granddaughter were honored the passing of pre sent for breakfast and presented with the oil painting. -

Review of Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981 by Stephen Tatum

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 1984 Review of Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981 By Stephen Tatum Kent L. Steckmesser California State University-Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Steckmesser, Kent L., "Review of Inventing Billy the Kid: Visions of the Outlaw in America, 1881-1981 By Stephen Tatum" (1984). Great Plains Quarterly. 1798. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1798 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 182 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, SUMMER 1984 biography was formulated as a "romance." As a "bad" badman, a threat to the moral order, the Kid had to die so that civilization-repre sented by Sheriff Pat Garrett-could advance. This formula of conflict and resolution by death can be detected in dime novels and early magazine accounts, which dwell on the Kid's unheroic appearance and bloodthirsty char acter. After a period of meager interest, by the mid-1920s a quite different figure was being molded by biographers and film makers. This was the prototypical "good" badman, one who personifies a kind of idealism. In Walter Noble Burns's key biography in 1926 and in a 1930 film, the Kid becomes a redeemer who helps small farmers. -

Police Abuse and Misconduct Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in the U.S

United States of America Stonewalled : Police abuse and misconduct against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the U.S. 1. Introduction In August 2002, Kelly McAllister, a white transgender woman, was arrested in Sacramento, California. Sacramento County Sheriff’s deputies ordered McAllister from her truck and when she refused, she was pulled from the truck and thrown to the ground. Then, the deputies allegedly began beating her. McAllister reports that the deputies pepper-sprayed her, hog-tied her with handcuffs on her wrists and ankles, and dragged her across the hot pavement. Still hog-tied, McAllister was then placed in the back seat of the Sheriff’s patrol car. McAllister made multiple requests to use the restroom, which deputies refused, responding by stating, “That’s why we have the plastic seats in the back of the police car.” McAllister was left in the back seat until she defecated in her clothing. While being held in detention at the Sacramento County Main Jail, officers placed McAllister in a bare basement holding cell. When McAllister complained about the freezing conditions, guards reportedly threatened to strip her naked and strap her into the “restraint chair”1 as a punitive measure. Later, guards placed McAllister in a cell with a male inmate. McAllister reports that he repeatedly struck, choked and bit her, and proceeded to rape her. McAllister sought medical treatment for injuries received from the rape, including a bleeding anus. After a medical examination, she was transported back to the main jail where she was again reportedly subjected to threats of further attacks by male inmates and taunted by the Sheriff’s staff with accusations that she enjoyed being the victim of a sexual assault.2 Reportedly, McAllister attempted to commit suicide twice. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable.