Kultur, Veränderung Sport: Culture, Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Schools Championships 2015 - Part 1

ISF FOUNDATION | INSIDE ISF WSC WSC Swim Cup Tennis SPECIAL EDITION World Schools Championships 2015 - Part 1 #05 | July 2015 2 | PORTFOLIO | ISF WSC BASKETBALL, ORIENTEERING, FOOTBALL AND SWIM CUP ISF WSC BASKETBALL, ORIENTEERING, FOOTBALL AND SWIM CUP | PORTFOLIO | 3 ISF Magazine | APRIL 2015 THE PRESIDENT’S #05 | JULY 2015 Rendezvous 2 | Portfolio 2 ISF WSC Basketball, Orienteering, Football and Swim Cup 5 | The President’s Rendezvous Since March 2015, nine ISF World follow us on the social networks which Schools Championships took place on actively publish news, results, pictures 6 | Best #ISFWSC2015 four different continents of the world. and videos. Each championship was spectacular 8 | and unique. This edition cannot contain I am also delighted to announce that I Special WSC 2015 – Tennis all the information I would like to share have taken the decision to devote a spe- 6 in order for readers to connect with the cial agenda, viz. to meet all the members 9 | Special WSC 2015 – Orienteering beauty and power of an international per continent from June 2015 to De- sport event gathering involving so many cember 2015 to continue the discus- | nationalities. Therefore, this edition and sions about the vision for ISF started 10 Special WSC 2015 – Swim Cup also the one being ipublished in Sep- during the ISF Convention.In addition, tember will only be devoted to World I am establishing two annual meetings 11 | Special WSC 2015 – Football Schools Championships. I hope to see with the continental presidents to in- soon even more countries and students clude them in the policy discussions of taking part in our championships. -

Guam National Olympic Committee

Guam National Olympic Committee Residency Guidelines 715 Route 8, Maite, Guam 96910 . T 1.671.647.4662 . F 1.671.646.4233 . [email protected] Guam National Olympic Committee Determining Residency Gaining Residency Eligibility: In order to be considered an athlete representing Guam under the umbrella of the Guam National Olympic Committee, the following requirements must be met by all athletes. The Athlete petitioning to be a part of Team Guam must: I. have a United States of America, Department of State issued passport (must provide the GNOC with a copy of such passport), II. have resided in Guam for five (5) years prior to the Opening of the Olympic Games, or in continental or regional games, or in the world or area championships - if born in Guam, must have five (5) cumulative years of residing in Guam prior to the Opening of the Games/Event. - if NOT born in Guam, the athlete must have resided in Guam for five (5) consecutive years prior to the Opening of the Games/Event (proof must be provided). III. provide proof of residency in one or more of the following ways in order to determine residency status: - a copy of five (5) consecutive years Guam Income Tax Filings - a certified letter or statement from the Government of Guam Department of Revenue and Taxation certifying the athlete (if under age, the athlete’s parent) has filed five (5) consecutive years prior to the Opening of Games/Event. - proof of owning real property in Guam (a copy of the property taxes paid to the Government of Guam Department of Revenue and Taxation or a statement from the Department stating the athlete has paid for five (5) consecutive years of property tax). -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

U.S. Citizenship Non-Precedent Decision of the and Immigration Administrative Appeals Office Services In Re: 8865906 Date: NOV. 30, 2020 Appeal of Nebraska Service Center Decision Form 1-140, Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker (Extraordinary Ability) The Petitioner, a martial arts athlete and coach, seeks classification as an alien of extraordinary ability. See Immigration and Nationality Act (the Act) section 203(b)(l)(A), 8 U.S.C. § l 153(b)(l)(A). This first preference classification makes immigrant visas available to those who can demonstrate their extraordinary ability through sustained national or international acclaim and whose achievements have been recognized in their field through extensive documentation. The Director of the Nebraska Service Center denied the petition, concluding that the record did not establish that the Petitioner met the initial evidence requirements through receipt of a major, internationally recognized award or meeting three of the evidentiary criteria at 8 C.F.R. § 204.5(h)(3). In these proceedings, it is the Petitioner's burden to establish eligibility for the requested benefit. See Section 291 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1361. Upon de nova review, we will dismiss the appeal. I. LAW Section 203(b)(l) of the Act makes visas available to immigrants with extraordinary ability if: (i) the alien has extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics which has been demonstrated by sustained national or international acclaim and whose achievements have been recognized in the field through extensive documentation, (ii) the alien seeks to enter the United States to continue work in the area of extraordinary ability, and (iii) the alien's entry into the United States will substantially benefit prospectively the United States. -

History of Tae Kwon Do.Pdf

Tae Kwon Do History Introduction: Although modern Taekwondo has actually only existed for about 50 years (the martial art known Tae Kwon Do was developed between 1945 and 1955 and only became known as Tae Kwon Do in 1955.), it is based upon Shotokan Karate, another 20th century martial art, and ancient Korea martial arts, such as Taekkyon and Subak, that have lost favor in modern times. Tae Kwon Do is a martial art that means "The Way of the Feet and Hands". Writings on Taekwondo history usually portray Taekwondo as an unique product of Korean culture, developed over the long course of Korean history since the Three Kingdoms Era. However, Taekwondo's primary influence came from Japanese Karate that was introduced into Korea during the Japanese occupation of Korea during the early 1900s. Few written records on ancient Korean history exist, so factual information on Korean martial arts is scarce and sketchy. Because of this, most Korean martial arts writers find something in Korean history to support their claims; writers on Tae Kwon Do included. If one researches the history of Tae Kwon Do, in the research they will find differing and sometimes contradictory information. Majority of this information is a summary taken from Reference 1. For more details, please review the entire material on history of Tae Kwon Do from Reference 1. Origins of Tae Kwon Do: Empty-hand fighting did not originate wholly in only one country, but it developed naturally in every place humans settled. In each country, people adapted their fighting techniques to deal with the dangers in their local environments. -

Steve Cotter

Kettlebell Training Steve Cotter HUMAN KINETICS Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cotter, Steve, 1970- Kettlebell training / Steve Cotter. pages cm 1. Kettlebells. 2. Weight training. I. Title. GV547.5.C68 2013 613.713--dc23 2013013814 ISBN-10: 1-4504-3011-2 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-3011-1 (print) Copyright © 2014 by Steve Cotter All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. This publication is written and published to provide accurate and authoritative information relevant to the subject matter presented. It is published and sold with the understanding that the author and publisher are not engaged in rendering legal, medical, or other professional services by reason of their authorship or publication of this work. If medical or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. The web addresses cited in this text were current as of August 2013, unless otherwise noted. Acquisitions Editor: Tom Heine; Developmental Editor: Laura Pulliam; Assistant Editor: Elizabeth Evans; Copyeditor: Alisha Jeddeloh; Graphic Designer: Joe Buck; Cover Designer: Keith Blomberg; Photograph (cover): © Tono Balaguer/easyFotostock; Photographs (interior): © Human Kinetics; Visual Production Assistant: Joyce Brumfield; Photo Production Manager: Jason Allen; Printer: United Graphics We thank Grinder Gym in San Diego, California, for assistance in providing the location for the photo shoot for this book. -

Auckland, New Zealand

IGLA 2016 AUCKLAND IGLA Auckland 2016 IGLA in Auckland .............................................................................................................................................. 3 IGLA Swim Festival ...................................................................................................................................... 3 West Wave Pool & Leisure Centre ............................................................................................................ 4 Team Auckland Masters Swimmers – IGLA Hosts ................................................................................. 5 LGBTI Sports in Auckland ................................................................................................................................ 7 Participation .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Our Community ............................................................................................................................................ 7 2016 Outgames ............................................................................................................................................... 8 2016 Outgames Sports Programme ........................................................................................................ 8 Outgames Human Rights Forum ............................................................................................................... 8 Outgames Cultural -

Sl Dovid V3:Layout 1.Qxd

НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ НАУК УКРАЇНИ ІНСТИТУТ ІСТОРІЇ УКРАЇНИ УКРАЇНА В МІЖНАРОДНИХ ВІДНОСИНАХ Енциклопедичний словник-довідник Випуск 3 Предметно-тематична частина: К–О Київ 2012 Україна в міжнародних відносинах. Енциклопедичний словник-довідник. Випуск 3. Предметно-тематична частина: К–О / Відп. ред. М.М. Варварцев. — К.: Ін-т історії України НАН України, 2012. — 315 с. Випуск 3 є продовженням започаткованого в 2009 р. словника, присвяченого історії міжнародних зв’язків України. У виданні висвітлюються події політики, економіки, культури від часів Давньоруської держави до початку ХХІ ст. Видання розраховане на науковців, викладачів, студентів, усіх, хто вивчає і бере участь у взаєминах із зарубіжним світом. Редакційна колегія: М.М. Варварцев (відповідальний редактор), С.В. Віднянський (керівник авторсь кого колективу), О.М. Горенко, О.А. Іваненко (відповідальний секретар), А.Ю. Мартинов Рецензенти: Г.В. Касьянов, доктор історичних наук О.С. Рубльов, доктор історичних наук, професор Авторський колектив: Алексієвець Л.М., Анікєєв Д.О., Барановська Н.П., Білоус Н.О., Блануца А.В., Бур’ян М.С., Варварцев М.М., Ващук Д.П., Віднянський С.В., Горенко О.М., Горобець В.М., Гула К.О., Гурбик А.О., Гуцол О.В., Дерейко І.І., Дзюба О.М., Зленко А.М., Єфіменко Г.Г., Іваненко О.А., Ісаєвич Я.Д., Ішуніна Н.В., Качараба С.П., Качмар В.М, Кірсенко М.В., Котляр М.Ф., Кресін О.В., Кривець Н.В., Кри жа - новська О.О., Кульчицький С.В., Лисенко О.Є., Мартинов А.Ю., Матяш І.Б., Мицик Ю.А., Набока О.В., Павленко М.І., Пастушенко Т.В., Пасько А.В., Першина Т.С., Пиріг Р.Я., Писаний Д.М., Піскіжова В.В., Примаченко Я.Л., Рендюк Т.Г., Рубльов О.С., Рубльова Н.С., Станіславський В.В., Степанков В.С., Стрикун І.С., Усенко І.Б., Черевко О.С., Черкас Б.В., Ярко Н.А. -

OOP-2013-00348 Announcement of the Next Executive Council of B.C

Page 1 OOP-2013-00348 Announcement of the next Executive Council of B.C. Friday, June 7, 2013 - 2:00 p.m. Invitation List - Invitee Guests Bonnie Abram Scott Anderson Lyn Anglin Olin Anton Robert Anton Helen Armstrong Mike Arnold Mike Arnold Deb Arnott Peter Ashcroft Antonia Audette Dave Bedwell Cindy Beedie Dr. Deborah Bell Jim Belsheim Beth Bennett Glenn Berg Valerie Bernier Ben Besler John Bishop Peter Boddy Bill Bond Michael Brooks Richard Bullock Matt Burke Cindy Burton Sandy Butler Daniel Cadieux George Cadman Marife Camerino Karen Cameron Murray Campbell S 22 Clark Campbell S 22 S 22 S 22 Alicia Campbell Lee Campbell S 22 Clark Campbell Page 2 OOP-2013-00348 Announcement of the next Executive Council of B.C. Friday, June 7, 2013 - 2:00 p.m. Invitation List - Invitee Guests Resja Campfens Sandi Case Ken Catton Cindy Chan Pius Chan James Chase Michael Chiu J. Brock Chrystal Charlotte Clark Jonathan Clarke Anita Clegg Susan Clovechok Susan Clovechok Lynette Cobb Hilda Colwell Tom Corsie Wayne Coulson Sharon Crowson Warren Cudney Warren Cudney Michael Curtiss Marlene Dalton Brian Daniel Bette Daoust Bette Daoust Francois Daoust Francois Daoust Filip de Sagher Gabrielle DeGroot Marko Dekovic Nilu Dhaliwal Lysa Dixon Rada Doyle Wayne Duzita Urmila Dwivedi John Eastwood Vivian Edwards Scott Ellis Barbara Elworthy Mark Elworthy Evangeline Englezos Warren Erhart Ida Fallowfield Charlene Fassbender Mr. Steve Fassbender Mrs. Steve Fassbender Page 3 OOP-2013-00348 Announcement of the next Executive Council of B.C. Friday, June 7, 2013 - 2:00 -

Commonwealth Games Research

Updated Review of the Evidence of Legacy of Major Sporting Events: July 2015 social Commonwealth Games research UPDATED REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE OF LEGACY OF MAJOR SPORTING EVENTS: JULY 2015 Communities Analytical Services Scottish Government Social Research July 2015 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Context of the literature review 1 Structure of the review 2 2. METHOD 3 Search strategy 3 Inclusion criteria 4 2015 Update Review Method 4 3. OVERVIEW OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE 6 Legacy as a ‘concept’ and goal 6 London focus 7 4. FLOURISHING 8 Increase Growth of Businesses 8 Increase Movement into Employment and Training 13 Volunteering 17 Tourism Section 19 Conclusion 24 2015 Addendum to Flourishing Theme 25 5. SUSTAINABLE 28 Improving the physical and social environment 28 Demonstrating sustainable design and environmental responsibility 30 Strengthening and empowering communities 32 Conclusion 33 2015 Addendum to Sustainable Theme 33 6. ACTIVE 37 Physical activity and participation in sport 37 Active infrastructure 40 Conclusion 42 2015 Addendum to Active Theme 43 7. CONNECTED 44 Increase cultural engagement 44 Increase civic pride 46 Perception as a place for cultural activities 47 Enhance learning 49 Conclusion 49 2015 Addendum to Connected Theme 50 8. AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH 51 9. CONCLUSIONS 52 10. REFERENCES 54 References 1st October 2013 to 30th September 2014 64 APPENDIX 67 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The aim of this evidence review is to establish whether major international multi-sport events can leave a legacy, and if so, what factors are important for making that happen. This edition of the original Kemlo and Owe (2014) review provides addendums to each legacy theme based on literature from 1st October 2013 to the end of September 2014. -

REPORT : 26Th TAFISA WORLD CONGRESS 2019 Tokyo

26th TAFISA WORLD CONGRESS 2019 Tokyo “Sport for All Through Tradition and Innovation” REPORT Date: 13th ~ 16th November 2019 Venue: Toshi Center Hotel Tokyo & Kojimachi Junior High School Organiser Hosts Japan Sports Agency Japanese Olympic Committee Supporters Special Partner Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japanese Para-Sports Association Congress Sponsors Partner History of TAFISA World Congress No. Year Host city & country 1st 1969 Oslo, Norway 2nd 1971 Arnhem, Netherlands 3rd 1973 Frankfurt am Main, Germany 4th 1975 Washington, D.C., USA 5th 1977 Paris, France 6th 1979 Lisbon, Portugal 7th 1981 Mürren, Switzerland 8th 1983 Stockholm, Sweden 9th 1985 Islay, United Kingdom 10th 1987 Oslo, Norway 11th 1989 Toronto, Canada 12th 1991 Bordeaux, France 13th 1993 Chiba, Japan 14th 1995 Netanye, Israel 15th 1997 Penang, Malaysia 16th 1999 Larnaka, Cyprus 17th 2001 Cape Town, South Africa 18th 2003 Munich, Germany 19th 2005 Warsaw, Poland 20th 2007 Buenos Aires, Argentina 21st 2009 Taiwan, Chinese Taipei 22nd 2011 Antalya, Turkey 23rd 2013 Enschede, Netherlands 24th 2015 Budapest, Hungary 25th 2017 Seoul, Korea 26th 2019 Tokyo, Japan Table of Contents Greetings ................................................................................................................... 2 26th TAFISA WORLD CONGRESS 2019 Tokyo - Overview ..................................................................................................................... 4 - Participants (Countries/Regions) ............................................................................... -

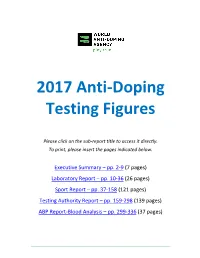

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples).