Jack the Giant Killer Information File (PDF Okt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Preview Only

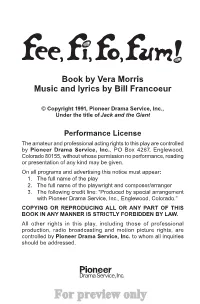

Book by Vera Morris Music and lyrics by Bill Francoeur © Copyright 1991, Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Under the title of Jack and the Giant Performance License The amateur and professional acting rights to this play are controlled by Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., PO Box 4267, Englewood, Colorado 80155, without whose permission no performance, reading or presentation of any kind may be given. On all programs and advertising this notice must appear: 1. The full name of the play 2. The full name of the playwright and composer/arranger 3. The following credit line: “Produced by special arrangement with Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Englewood, Colorado.” COPYING OR REPRODUCING ALL OR ANY PART OF THIS BOOK IN ANY MANNER IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN BY LAW. All other rights in this play, including those of professional production, radio broadcasting and motion picture rights, are controlled by Pioneer Drama Service, Inc. to whom all inquiries should be addressed. For preview only FEE, FI, FO, FUM! Adapted and dramatized from the Benjamin Tabart version of the English folktale, “The History of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean” Book by VERA MORRIS Music and Lyrics by BILL FRANCOEUR CAST OF CHARACTERS (In Order Of Appearance) # of lines JACK ................................................brave young lad; loves 149 adventure SUSAN .............................................his sister 53 JACK’S MOTHER .............................about to lose her farm 65 VILLAGE WOMAN #1 ......................lives in fear of the Giant 11 VILLAGE WOMAN #2 ......................more -

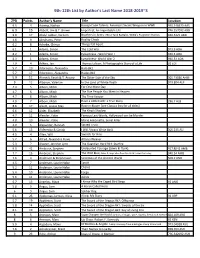

9Th-12Th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S

9th-12th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 9.5 4 Aaseng, Nathan Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in WWII 940.548673 AAS 6.9 15 Abbott, Jim & T. Brown Imperfect, An Improbable Life 796.357092 ABB 9.9 17 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Brothers in Arms: 761st Tank Battalio, WW2's Forgotten Heroes 940.5421 ABD 4.6 9 Abrahams, Peter Reality Check 6.2 8 Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart 6.1 1 Adams, Simon The Cold War 973.9 ADA 8.2 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness - World War I 940.3 ADA 8.3 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness- World War 2 940.53 ADA 7.9 4 Adkins, Jan Thomas Edison: A Photographic Story of a Life 92 EDI 5.7 19 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo Bk1 5.7 17 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades Bk2 5.9 11 Ahmedi, Farah & T. Ansary The Other Side of the Sky 305.23086 AHM 9 12 Albanov, Valerian In the Land of White Death 919.804 ALB 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For One More Day 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper 4.9 7 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: a True Story 296.7 ALB 8.6 17 Alcott, Louisa May Rose in Bloom [see Classics lists for all titles] 6.6 12 Alder, Elizabeth The King's Shadow 4.7 11 Alender, Katie Famous Last Words, Hollywood can be Murder 4.8 10 Alender, Katie Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer 4.9 5 Alexander, Hannah Sacred Trust 5.6 13 Aliferenka & Ganda I Will Always Write Back 305.235 ALI 4.5 4 Allen, Will Swords for Hire 5.2 6 Allred, Alexandra Powe Atticus Weaver 5.3 7 Alvarez, Jennifer Lynn The Guardian Herd Bk1: Starfire 9.0 42 Ambrose, Stephen Undaunted Courage -

Giant Hogweed Please Destroy Previous Editions

MSU Extension Bulletin E-2935 June 2012 Giant Hogweed Please destroy previous editions An attractive but dangerous federal noxious weed. Have you seen this plant in Michigan? Hogweed is hazardous Wash immediately with soap and water if skin exposure occurs. If pos- Giant hogweed is a majestic plant sible, keep the contacted area cov- that can grow over 15 feet. Although ered with clothing for several days to attractive, giant hogweed is a public reduce light exposure. Giant hogweed health hazard because it can cause se- (Heracleum mantegazzianum) is a vere skin irritation in susceptible people. federal noxious weed, so it is unlaw- The plant exudes a clear, watery sap that ful to propagate, sell or transport this causes photodermatitis, a severe skin plant in the United States. The U.S. reaction. Skin contact followed by ex- Department of Agriculture (USDA) posure to sunlight may result in painful, has been surveying for this weed since burning blisters and red blotches that 1998 and several infestations have later develop into purplish or blackened been identified in Michigan. For more USDA APHIS PPQ Archive, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org Archive, USDA APHIS PPQ USDA scars. The reaction can happen within information about giant hogweed, visit It’s a tall majestic plant, 24 to 48 hours after contact with sap, the Michigan Department of Agricul- and scars may persist for several years. ture and Rural Development at www. but DON’T TOUCH IT! Contact with the eyes can lead to tempo- michigan.gov/exoticpests. rary or permanent blindness. Use common sense around giant hogweed Don’t touch or handle plants using Don’t transplant or give away your bare hands. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Jack and the Beanstalk

Oxford Level 5 Jack and the Beanstalk Written by Gill Munton and illustrated by Constanze von Kitzing Teaching notes written by Thelma Page Information about assessment and curriculum links can be found at the end of these Teaching Notes. Background to the story • Traditional tales have been told for many years. They help to keep alive the richness of storytelling language and traditions from different cultures. These tales, many of which will be familiar to the children, are rich in patterned language and provide a springboard for their own storytelling and writing. • This story is based on ‘The History of Jack and the Beanstalk’ which was first published about two hundred years ago. It is an old English folk tale. Group/Guided reading Introducing the story • Look at the cover of the book and read the title together. Ask: What is a beanstalk? What is Jack doing on the front cover? • All the words in this story are decodable for this stage. You can look together at the inside front cover for a list of the high frequency tricky words for this stage used in the book, to help build familiarity with these before children read the story independently. Reading the extended story • Read the extended story (on page 69 of the Traditional Tales Handbook) to the children. Use the pupil book to show the images to the children as you read, and pause during the story to ask questions. • Stop reading at the end of page 5. Ask: Do you think Jack’s mum will be pleased with the beans? • Pause at the end of page 7. -

Jack and the Beanstalk by Farah Farooqi Illustrated by Ingrid Sundberg Table of Contents

Jack and the Beanstalk By Farah Farooqi Illustrated by Ingrid Sundberg Table of Contents Chapter One Magic Beans ..............................................................................1 Chapter Two Meet the Giants .....................................................................6 Chapter Three A Piece of Cake .................................................................. 11 © 2011 Wireless Generation, Inc. All rights reserved. MagicChapter Beans One Once upon a time, there was a poor woman. She lived with her son, Jack. They had a cow named Barky. They sold Barky’s milk at the market to make money. One morning, Barky gave no milk. She had become old. Jack’s mother was worried. Without milk, they would see horrible times. Title: Jack and the Beanstalk Page: 1 “What will we do?” she wondered. “Maybe we should sell Barky. The money could help us buy food,” suggested Jack. “Good idea, Jack. Go to the market, and see how much you could get for her,” she replied. Jack had not gotten very far when his old neighbor, Mr. Bones, approached him. “Hi, Jack,” Mr. Bones said. “Where are you going?” Title: Jack and the Beanstalk Page: 2 “I’m going to the market to sell Barky,” said Jack. “I don’t see a dog,” said Mr. Bones. “Well, I really wanted a dog. But we couldn’t afford one, so I named the cow Barky,” explained Jack. “Interesting. My dog’s name is Moo,” said Mr. Bones. “Is that because you always wanted a cow?” asked Jack. “Yes. In fact, I want your cow. So let’s make a deal. I’ll give you five beans for your cow,” answered Mr. Bones. “I don’t really like beans,” frowned Jack. -

" Dragon Tales." 1992 Montana Summer Reading Program. Librarian's Manual

-DOCUMENT'RESUME------ ED 356 770 IR 054 415 AUTHOR Siegner, Cathy, Comp. TITLE "Dragon Tales." 1992 Montana Summer Reading Program. Librarian's Manual. INSTITUTION Montana State Library, Helena. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 120p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reference Arterials Bibliographies (131) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Braille; *Childrens Libraries; *Childrens Literature; Disabilities; Elementary Education; Games; Group Activities; Handicrafts; *Library Services; Program Descriptions; Public Libraries; *Reading Programs; State Programs; Story Telling; *Summer Programs; Talking Books IDENTIFIERS *Montana ABSTRACT This guide contains a sample press release, artwork, bibliographies, and program ideas for use in 1992 public library summer reading programs in Montana. Art work incorporating the dragon theme includes bookmarks, certificates, reading logs, and games. The bibliography lists books in the following categories: picture books and easy fiction (49 titles); non-fiction, upper grades (18 titles); fiction, upper grades (45 titles); and short stories for easy telling (13 titles). A second bibliography prepared by the Montana State Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped provides annotations for 133 braille and recorded books. Suggestions for developing programs around the dragon and related themes, such as the medieval age, knights, and other mythic creatures, are provided. A description of craft projects, puzzles, and other activities concludes -

The Logic of the Grail in Old French and Middle English Arthurian Romance

The Logic of the Grail in Old French and Middle English Arthurian Romance Submitted in part fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Martha Claire Baldon September 2017 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 8 Introducing the Grail Quest ................................................................................................................ 9 The Grail Narratives ......................................................................................................................... 15 Grail Logic ........................................................................................................................................ 30 Medieval Forms of Argumentation .................................................................................................. 35 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................. 44 Narrative Structure and the Grail Texts ............................................................................................ 52 Conceptualising and Interpreting the Grail Quest ............................................................................ 64 Chapter I: Hermeneutic Progression: Sight, Knowledge, and Perception ............................... 78 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... -

Fairy Tales on the Big and Small Screen

9 Fairy Tales on the Big and Fairy tale movies have appeal because they Small Screen provide a point of familiarity for a developing teen audience; the plot lines of by Pia Dewar modern remakes like The Brothers’ Grimm The realm of fairy tales and storytelling has (2005), or Red Riding Hood (2011) are been with us for hundreds of years. Fairy familiar to what we remember from tales have evolved over time, but have not children’s stories even though the visual lost their appeal (especially to children, and presentation and the tone can be very young adults). Fairy tales in particular have different (Kroll, 2011, p. 1). This alteration proven adaptive in the ever-growing variety to presentation has been popular, given the of media and modern movie remakes. Kroll string of popular remake movies in recent comments in his article, “studios are years as Wood notes, “modern fantasy film endlessly searching for familiar properties audiences frequently come to them first as with name recognition and spinoff children and keep returning to them potential” and with several remakes throughout adolescence and adulthood, and released in the last few years (all of which this blurs the child/adult distinctions,” are listed at the end of this article as (2006, p. 287). Beginning with the Twilight pertinent examples) this certainly seems to franchise that “put a modern twist on overly be true (2011, p. 4). Fairy tales are so familiar characters,” this shows how we are malleable, that they allow movie producers attracted to novelty with a touch of the to make motion picture remakes that are familiar (Kroll, 2011, p. -

Movies July & August

ENTERTAINMENT Pick your blockbuster! Who better to decide which movies are included in our inflight Language Selection entertainment programme than our passengers? Every month, you get to pick the blockbusters shown on English (EN), French (FR), German (DE), Dutch (NL), Italian (IT), Spanish (ES), Movies July & August Available in Business Class & Economy Class our long haul flights. Simply go to our Facebook page and cast your votes!facebook.com/brusselsairlines Portuguese (PT), Dutch subtitles (NL), English subtitles (EN) ˜ ACTION ˜ Oblivion Jack the Giant Slayer I Don’t Know The Hangover Part II ˜ DRAMA ˜ Hugo Mama Africa Ice Age: Dawn Ever After: PG PG R 13 13 PG NR A Good Day to Die Hard 125mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 114mins (2012) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL How She Does It 102 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 42 120mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 90 mins (2011) EN, FR Of The Dinosaurs A Cinderella Story R PG PG PG PG 97 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman Ewan McGregor, Ian McShane 13 96 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms 13 128 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Ben Kingsley, Asa Butterfield Miriam Makeba 94 mins (2009) EN, FR, NL, DE, ES, IT 13 121 mins (1998) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT Bruce Willis, Jai Courtney Sarah Jessica Parker, Pierce Brosnan Chadwick Boseman, Harrison Ford Ray Romano, Denis Leary Drew Barrymore, Anjelica Huston JULY FROM JULY FROM FROM JULY ONLY AUGUST ONLY AUGUST AUGUST ONLY From Russia With Love Tomorrow Never Dies Percy -

Of Titles (PDF)

Alphabetical index of titles in the John Larpent Plays The Huntington Library, San Marino, California This alphabetical list covers LA 1-2399; the unidentified items, LA 2400-2502, are arranged alphabetically in the finding aid itself. Title Play number Abou Hassan 1637 Aboard and at Home. See King's Bench, The 1143 Absent Apothecary, The 1758 Absent Man, The (Bickerstaffe's) 280 Absent Man, The (Hull's) 239 Abudah 2087 Accomplish'd Maid, The 256 Account of the Wonders of Derbyshire, An. See Wonders of Derbyshire, The 465 Accusation 1905 Aci e Galatea 1059 Acting Mad 2184 Actor of All Work, The 1983 Actress of All Work, The 2002, 2070 Address. Anxious to pay my heartfelt homage here, 1439 Address. by Mr. Quick Riding on an Elephant 652 Address. Deserted Daughters, are but rarely found, 1290 Address. Farewell [for Mrs. H. Johnston] 1454 Address. Farewell, Spoken by Mrs. Bannister 957 Address. for Opening the New Theatre, Drury Lane 2309 Address. for the Theatre Royal Drury Lane 1358 Address. Impatient for renoun-all hope and fear, 1428 Address. Introductory 911 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of Drury Lane Theatre 1827 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of the Hay Market Theatre 2234 Address. Occasional. In early days, by fond ambition led, 1296 Address. Occasional. In this bright Court is merit fairly tried, 740 Address. Occasional, Intended to Be Spoken on Thursday, March 16th 1572 Address. Occasional. On Opening the Hay Marker Theatre 873 Address. Occasional. On Opening the New Theatre Royal 1590 Address. Occasional. So oft has Pegasus been doom'd to trial, 806 Address. -

KOERNER S HAVES by BUFFALO N Vv

; KOERNER S HAVES BY BUFFALO N Vv ! = \A #1 t : 4 ¢ Jack the Giant=Killer. The Giant Stepped on Jack’s Trap and Fell Headlong into the Pit. [° the days of the renowned King Arthur there lived a Cornishman named Jack, who was famous for his valiant deeds. His bold and warlike spirit showed itself in his boyish days; for Jack took especial delight in listening to the wonderful tales of giants and fairies, and of the extraordinary feats of valor displayed by the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table, which his father would sometimes relate. Jack’s spirit was so fired by these strange accounts, that he determined, if ever he became a man, that he would destroy some of the cruel giants who infested the land. Not many miles from his father’s house there lived, on the top of St. Michael’s Mount, a huge giant, who was the terror of the country round, who was named Cormoran, from his voracious appetite. It is said that he was eighteen feet in height. When he required food, he came down from his castle, and, seizing on the flocks of the poor people, would throw half a dozen oxen over his shoulders, and suspend as many sheep as he could carry, and stalk back to his castle. He had carried on these depredations many years ; and the poor Cornish people were well-nigh ruined. Jack went by night to the foot of the mount and dug a very deep pit, which he covered with sticks and straw, and over which he strewed the earth.