Western Esotericism,Yoga, and the Discourse of Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Tantrasâra Abhinavagupta

Tantrasâra Abhinavagupta Tantrasara of Abhinavagupta Translated from Sanskrit with Introduction and Notes by H.N. Chakravarty Edited by Boris Marjanovic Preface by Swami Chetanananda Rudra Press Published by Rudra Press P.O. Box 13310 Portland, OR 97213-0310 503-236-0475 www.rudrapress.com Copyright© H.N. Chakravarty, 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Cover art by Ana Capitaine ~ Cover design by Guy Boster Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abhinavagupta, Rajanaka. [Tantrasara. English] Tantrasara of Abhinavagupta / translated from Sanskrit with introduction and notes by H.N. Chakravarty ; edited by Boris Marjanovic ; preface by Swami Chetanananda. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-915801-78-7 1. Kashmir Saivism-Early works to 1800. 2. Tantrism-Early works to 1800. 3. Abhinavagupta, Rajanaka. Tantraloka. I. Chakravarty, H.N., 1918-2011, translator, writer of added commentary. II. Marjanovic, Boris, editor. III. Abhinavagupta, Rajanaka. Tantraloka. IV. Title. BL1281.154.A3513 2012 294.5*95—dc23 2012008126 Contents Preface by Swami Chetanananda vii Foreword by Boris Marjanovic ix Introduction by H.N. Chakravafty 1 Abhinavagupta’s Tantrasara 51 Chapter One 51 Chapter Two 58 Chapter Three 60 Chapter Four 67 Chapter Five 79 Chapter Six 87 Chapter Seven 101 Chapter Eight 107 Chapter Nine 123 Chapter Ten 135 Chapter Eleven 140 Chapter Twelve 148 Chapter Thirteen 152 Chapter Fourteen 168 Chapter Fifteen 173 v VI CONTENTS Chapter Sixteen 175 Chapter Seventeen 179 Chapter Eighteen 181 Chapter Nineteen 183 Chapter Twenty 186 Chapter Twenty-One 201 Chapter Twenty-Two 205 Notes 215 Bibliography 265 About the Translator 267 About Rudra Press 269 Preface One day in May of 1980 in South Fallsburg, I was sitting in my room in between programs at the Siddha Yoga Ashram reading some science fiction book, when Muktananda came, in the room. -

Dvaita Vedanta

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa Table of Contents Dvaita System Of Vedanta ................................................ 1 Cognition ............................................................................ 5 Introduction..................................................................... 5 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception .......................................... 6 Anumana, Inference ....................................................... 9 Sabda, Word Testimony ............................................... 10 Metaphysical Categories ................................................ 13 General ........................................................................ 13 Nature .......................................................................... 14 Individual Soul (Jiva) ..................................................... 17 God .............................................................................. 21 Purusartha, Human Goal ................................................ 30 Purusartha .................................................................... 30 Sadhana, Means of Attainment ..................................... 32 Evolution of Dvaita Thought .......................................... 37 Madhva Hagiology .......................................................... 42 Works of Madhva-Sarvamula ......................................... 44 An Outline .................................................................... 44 Gitabhashya ................................................................ -

Shakti and Shkta

Shakti and Shâkta Essays and Addresses on the Shâkta tantrashâstra by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), London: Luzac & Co., [1918] Table of Contents Chapter One Indian Religion As Bharata Dharma ........................................................... 3 Chapter Two Shakti: The World as Power ..................................................................... 18 Chapter Three What Are the Tantras and Their Significance? ...................................... 32 Chapter Four Tantra Shastra and Veda .......................................................................... 40 Chapter Five The Tantras and Religion of the Shaktas................................................... 63 Chapter Six Shakti and Shakta ........................................................................................ 77 Chapter Seven Is Shakti Force? .................................................................................... 104 Chapter Eight Cinacara (Vashishtha and Buddha) ....................................................... 106 Chapter Nine the Tantra Shastras in China................................................................... 113 Chapter Ten A Tibetan Tantra ...................................................................................... 118 Chapter Eleven Shakti in Taoism ................................................................................. 125 Chapter Twelve Alleged Conflict of Shastras............................................................... 130 Chapter Thirteen Sarvanandanatha ............................................................................. -

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’S Vaisnava Theism

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa 1 2 Table of Contents Page No Preface 5 1. Dvaita System of Vedanta 7 2. Conginition 9 Introduction 9 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception 10 Anumana, Inference 12 Sabda, Word Testimony 13 3. Metaphysical Categories 15 General 15 Nature 16 Individual Soul (Jiva) 18 God 20 4. Purusartha, Human Goal 25 Purusartha, Human Goal 25 Sadhana, Means of Attainment 27 5. Evolution of Dvaita Thought 30 6. Madhva Hagiology 33 7. Works of Madhva–Sarvamula 35 An Outline 35 Gita Bhashya 38 Gita Tatparya 40 Sutra –Prasthana 42 General Brahmasutra Bhashya Anu Vyakhyana Nyaya Vivarana Anu Bhashya Bhagavata Tatparya 48 Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya 49 Dasa-Prakaranas 52 Pramanalaksana Kathalaksana Upadhi Khandana Prapanca-Mithyatvanumana Khandana Mayavada Khandana Tattva Samkhyanam Tattva Viveka Tattvoddyota Visnu Tattva Nirnaya Karma Nirnaya Upanisad Bhashyas 59 General 3 Isavasya Upanisad Bhashya Kena or Talavakara Upanisad Bhashya Katha Upanisad Bhashya Mundaka Upanisad Bhashya Prasna Upanisad Bhashya Mandukya Upanisad Bhashya Aitareya Upanisad Bhashya Taittiriya Upanisad Bhashya Brhadaranyaka Upanisad Bhashya Chhandogya Upanisad Bhashya Rigveda Bhashya 66 Stotras, and Works on Worship and Rituals 69 8. Jayatirtha 72 General 72 Works of Jayatirtha 73 9. Visnudasa 76 10. Vyasatirtha 79 General 79 Works of Vyasatirtha 80 11. Other Madhva Pontiffs 84 Vijayendratirtha Vadirajatirtha Narayanacarya Vidyadhirajatirtha Vyasatirtha Vijayadhavajatirtha Sudhindratirtha Vidyadhisatirtha Visvesvaratirtha Raghavendratirtha Brahmanyatirtha and Others 12. Haridasakuta 89 4 Preface Dualism, as understood in western philosophy, is a ‘theory which admits two independent and mutually irreducible substances’. Samkhya Dualism answers to this definition. But Madhva’s Dvaita, Dualism admits two mutually irreducible principles as constituting Reality as a whole, but regards only one of them, God as independent, svatantra and the other as dependent, paratantra. -

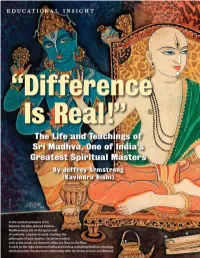

Difference Is Real”

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT The Life and Teachings of Sri Madhva, One of India’s Greatest Spiritual Masters By Jeffrey Armstrong (Kavindra Rishi) s. rajam In the constant presence of his Beloved, the blue-skinned Krishna, Madhvacharya sits on the guru’s seat of authority, scripture in hand, teaching the philosophy of pure dualism. Sectarian symbols, such as the conch, are drawn in white rice fl our on the fl oor. A nitch on the right enshrines Radha and Krishna, indicating Madhva’s theology, which describes the devotee’s relationship with the Divine as lover and Beloved. july/august/september, 2008 hinduism today 39 The Remarkable Life of Sri Madhvacharya icture a man off powerfulf physique, a champion wrestler, who They are not born and do not die, though they may appear to do so. tiny platform,f proclaimedd to the crowdd off devoteesd that Lordd Vayu, Vasudeva was physically and mentally precocious. Once, at the could eat hundreds of bananas in one sitting. Imagine a guru Avatars manifest varying degrees of Divinity, from the perfect, or the closest deva to Vishnu, would soon take birth to revive Hindu age of one, he grabbed hold of the tail of one of the family bulls who P who was observed to lead his students into a river, walk them Purna-Avatars, like Lord Rama and Lord Krishna, to the avatars of dharma. For twelve years, a pious brahmin couple of modest means, was going out to graze in the forest and followed the bull all day long. across the bottom and out the other side. -

The Tantrasara of Abhinava Gupta. Edited with Notes By

THE KASHMIR SERIES OF TEXTS AND STUDIES. c jtvntfi fit ate mid NO. xvn. THE TANTRASARA OF ABHINAVA GUPTA. Edited with notes by MAHAMAHOPADHYAYA PANDIT MUKUND RAM SHASTR1, Offlcer-in-Cliarge Eeseaxcli Department, JAMMU AND KASHMIR STATE, SRINAGAR, Published under the Authority of the Government of His Highness Lieut.-General Maharaja Sir PRATAP SINGH SAHIB BAHADUR, Q. C. S. I., Q. C. I. E., MAHARAJA OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR STATE, BOMBAY: PRINTED AT THE 'NIRNAYA-SAQAR' PRESS, 1918. PK 313/ ft 51 -..- % f 808994 . (All rights reserved). Printed by Ramchandra Yesu Shedge, at the 'Nirnaya-sagar' Press, 23, Kolbhat Lane, Bombay. Published by Mahamahopadhyaya Pandit Mukund Ram Shastri for the Research Department, Jammu and Kashmir State, SR1NAQAR. t i V II ^ II PREFATORY. Before introducing the reader to the most abstruse and technical contents of this philosophical work I take this opportunity to express my heartfelt thanks to the owners of the manuscripts which have been made the main bases of this edition of the Tantrasara, appearing for the first time as volume XVII of the Kashmir Series of Texts and Studies. In all there were three manuscript copies used in preparation of this work for the Press. The first of these belonging to RajanakaSodarshana of Srinagar con- sisted of 72 leaves of Kashmiri paper written in Sharada characters, and of this a copy was made in this office. It is a transcript of another older manuscript and bears 1903 anno Vikrami (1846 A.D.) as the date of its trans- cription. As regards omissions and mistakes it is, how- ever, not free from blemishes. -

Proofs of the Prophets: the Case for Lord Krishna

1 PROOFS OF THE PROPHETS: THE CASE FOR LORD KRISHNA Peter Terry Compiler and Commentator Volume VII, Bahá’í Studies Series Original compilation of texts related to Lord Krishna: Forty Proofs of Prophethood set forth in the Bhagavad-Gita, the Bhagavata Purana and other Scriptures of Hinduism, as well as the writings of Bahá’u’lláh, the Báb, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and other authors, in English translations. Passages from the Writings of the Báb are in some cases presented in the compiler’s rendering of their French translation by A.L.M. Nicolas, originally published circa 1900-1911. Published by Lulu Publications 2008 Copyright © 2008 by Peter TerryAll rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. ISBN: 978-0-557-06720-6 The essential requirement for whoso advanceth a claim is to support his assertions with clear proofs and testimonies.1 Some of the divines who have declared this Servant an infidel have at no time met with Me. Never having seen Me, or become acquainted with My purpose, they have nevertheless spoken as they pleased and acted as they desired. Yet every claim requireth a proof, not mere words and displays of outward piety.2 In this day the verses of the Mother Book are resplendent and unmistakable even as the sun. They can in no wise be mistaken for any past or more recent utterances. Truly this Wronged One desireth not to demonstrate His Own Cause with proofs produced by others. He is the One Who embraceth all things, while all else besides Him is circumscribed. -

The Myth of the Holy Cow

IWU * ** The Myth of the Holy Cow D.N. Jha navayana The Myth of the Holy Cow © D.N.Jha Published by Navayana Publishing, 2009 First published by Matrix Books, New Delhi, 2001 ISBN: 978-8189059163 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed by Sanjiv Palliwal, New Delhi Navayana Publishing M-100, 1 Floor, Saket, New Delhi 110017 navayana.org [email protected] Distributed by IPD Alternatives (www.ipda.in) and WestLand Books Pvt. Ltd. Chennai gam alabhate[2]; yajno vai gauh; . yajnarn eva labhate; atho annam vai gauh; annam evavarundhe. Taittiriya Brahmana, III. 9.8.2-3 (Anandasrama- sanskritgranthavalih 37, vol. Ill, 3rd.edn., Poona, 1979). ‘ (At the horse-sacrifice) he (the Adhvaryu) seizes (binds) the cow (i.e. cows). The cow is the sacrifice. (Consequently) it is the sacrifice he (the Sacrificer) thus obtains. And the cow certainly is food. (Consequently) it is food he thus obtains.’ English translation by Paul-Emile Dumont, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 92.6 (December 1948), p. 485. ‘. Silver foil or “varak” used for decorating sweets has more than just a pleasing look to it. It is made by placing thin metal strips between steaming intestines of freshly slaughtered animals. The metal is then pounded between ox-gut and the sheets are carefully transferred in .’ special paper for marketing. Bindu Jacob, ‘More to it all than meets the Eye’, The Hindu, 5 June 2001 (A news item based on a publication of the Animal Welfare Board of India under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India). -

Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls : Popular Goddess

Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal JUNE McDANIEL OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls This page intentionally left blank Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal june mcdaniel 1 2004 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Sa˜o Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright ᭧ 2004 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McDaniel, June. Offering flowers, feeding skulls : popular goddess worship in West Bengal / June McDaniel. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-19-516790-2; ISBN 0-19-516791-0 (pbk.) 1. Kali (Hindu deity)—Cult—India—West Bengal. 2. Shaktism—India—West Bengal. 3. West Bengal (India)— Religious life and customs. I. Title. BL1225.K33 W36 2003 294.5'514'095414—dc21 2003009828 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Acknowledgments Thanks go to the Fulbright Program and its representatives, whose Senior Scholar Research Fellowship made it possible for me to do this research in West Bengal, and to the College of Charleston, who granted me a year’s leave for field research. -

Kashmir Shaivism

KKaasshhmmiirr SShhaaiivviissmm PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir Shaivism Page Intentionally Left Blank ii KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)). PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir Shaivism KKaasshhmmiirr SShhaaiivviissmm First Edition, August 2002 KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)) iii PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir Shaivism Contents page Contents......................................................................................................................................v 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................1-2 2 Shaivistic and Bhakti Roots of Kashmiri Religion............................................................2-3 3 Kashmir Saivism..............................................................................................................3-6 4 Kashmir Saivism and its Echoes in Kashmiri Poetry.........................................................4-9 5 Kashmir Shaivism..........................................................................................................5-13 5.1 Hymn to Shiva Shakti.............................................................................................5-13 5.2 The Chart of Cosmology according to Kashmir Shavism........................................5-14 6 Saivism in Prospect