Tantrasâra Abhinavagupta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

Tantraloka Notes

Tantraloka Notes 1. ONE Tantraloka by george barselaar Of all the philosophical systems emanating from the east, Kashmir Shaivism stands alone in its subtle elucidation of the theory and practice of spirituality. Aptly labeled ‘the mystical geography of awareness’, the agamas(1) of Shaivism describe in microscopic detail the development of human consciousness from the grosses state of ignorance to the subtlest state of universal God consciousness. Drawing from these ancient scriptures–many of which are now lost–the great Shaiva master Abhinavagupta (10 CE), fashioned the monistic tradition known as Trika Rahasyam(2). After attaining God realization, Abhinavagupta states that out of curiosity he sat at the feet of many masters and like an industrious bee collected the nectar of the prominent philosophical traditions of his time. Completing this venture he returned to his own disciples and spontaneously sang thirty-seven philosophical hymns in the same number of days. This encyclopedic text became Abhinavagupta’s greatest philosophical work entitled Tantraloka. In thirty-seven chapters he unfolded the petals of his heart lotus of knowledge explaining the process of creation and evolution of the universe in term of the expansion of Shiva’s consciousness. He laid bare the secrets of the monistic system know today as Kashmir Shaivism. In his first chapter Abhinavagupta states clearly that he was impelled by Lord Shiva, his masters, and his closest disciples, to compose Tantraloka. In verse 284 of that same chapter he states: “That person who has read, achieved and understood the depth of these thirty-seven chapters becomes one with Bhairava-Lord Shiva.” ~Swami Lakshmanjoo In composing Tantraloka, Abhinavagupta drew inspiration from the Malinivijaya tantra(3), a text so cryptic in places that scholars of that time were at a loss to understanding it. -

Abhinavagupta's Theory of Relection a Study, Critical Edition And

Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in Chapter III of the Tantrāloka with the commentary of Jayaratha Mrinal Kaul A Thesis In the Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada August 2016 © Mrinal Kaul, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mrinal Kaul Entitled: Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection: A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in Chapter III of the Tantrāloka with the commentary of Jayaratha and submitted in partial fulillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the inal Examining Committee: _____________________________Chair Dr Christine Jourdan _____________________________External Examiner Dr Richard Mann _____________________________External to Programme Dr Stephen Yeager _____________________________Examiner Dr Francesco Sferra _____________________________Examiner Dr Leslie Orr _____________________________Supervisor Dr Shaman Hatley Approved by ____________________________________________________________ Dr Carly Daniel-Hughes, Graduate Program Director September 16, 2016 ____________________________________________ Dr André Roy, Dean Faculty of Arts and Science ABSTRACT Abhinavagupta’s Theory of Relection: A Study, Critical Edition and Translation of the Pratibimbavāda (verses 1-65) in the Chapter III of the Tantrāloka along with the commentary of Jayaratha Mrinal Kaul, Ph.D. Religion Concordia University, 2016 The present thesis studies the theory of relection (pratibimbavāda) as discussed by Abhinavagupta (l.c. 975-1025 CE), the non-dualist Trika Śaiva thinker of Kashmir, primarily focusing on what is often referred to as his magnum opus: the Tantrāloka. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Dvaita Vedanta

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa Table of Contents Dvaita System Of Vedanta ................................................ 1 Cognition ............................................................................ 5 Introduction..................................................................... 5 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception .......................................... 6 Anumana, Inference ....................................................... 9 Sabda, Word Testimony ............................................... 10 Metaphysical Categories ................................................ 13 General ........................................................................ 13 Nature .......................................................................... 14 Individual Soul (Jiva) ..................................................... 17 God .............................................................................. 21 Purusartha, Human Goal ................................................ 30 Purusartha .................................................................... 30 Sadhana, Means of Attainment ..................................... 32 Evolution of Dvaita Thought .......................................... 37 Madhva Hagiology .......................................................... 42 Works of Madhva-Sarvamula ......................................... 44 An Outline .................................................................... 44 Gitabhashya ................................................................ -

1 Essence of Paramartha Saara

ESSENCE OF PARAMARTHA SAARA (The Quintessence of Supreme Awareness) Edited and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities Essence of Manu Smriti*------------------- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. Kamakoti. Org/news as also on Google by the respective references. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 14 Fall 2012 TITLE iii The Buddhist Sanskrit Tantras: “The Samādhi of the Plowed Row” James F. Hartzell Center for Mind/Brain Sciences (CIMeC) University of Trento, Italy ABSTRACT This paper presents a discussion of the Buddhist Sanskrit tantras that existed prior to or contemporaneous with the systematic translation of this material into Tibetan. I have searched through the Tohoku University Catalogue of the Tibetan Buddhist canon for the names of authors and translators of the major Buddhist tantric works. With authors, and occasionally with translators, I have where appropriate converted the Tibetan names back to their Sanskrit originals. I then matched these names with the information Jean Naudou has uncov- ered, giving approximate, and sometimes specific, dates for the vari- ous authors and translators. With this information in hand, I matched the data to the translations I have made (for the first time) of extracts from Buddhist tantras surviving in H. P. Śāstrī’s catalogues of Sanskrit manuscripts in the Durbar Library of Nepal, and in the Asiatic Society of Bengal’s library in Calcutta, with some supplemental material from the manuscript collections in England at Oxford, Cambridge, and the India Office Library. The result of this research technique is a prelimi- nary picture of the “currency” of various Buddhist Sanskrit tantras in the eighth to eleventh centuries in India as this material gained popu- larity, was absorbed into the Buddhist canon, commented upon, and translated into Tibetan. I completed this work in 1996, and have not had the opportunity or means to update it since. -

Shakti and Shkta

Shakti and Shâkta Essays and Addresses on the Shâkta tantrashâstra by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), London: Luzac & Co., [1918] Table of Contents Chapter One Indian Religion As Bharata Dharma ........................................................... 3 Chapter Two Shakti: The World as Power ..................................................................... 18 Chapter Three What Are the Tantras and Their Significance? ...................................... 32 Chapter Four Tantra Shastra and Veda .......................................................................... 40 Chapter Five The Tantras and Religion of the Shaktas................................................... 63 Chapter Six Shakti and Shakta ........................................................................................ 77 Chapter Seven Is Shakti Force? .................................................................................... 104 Chapter Eight Cinacara (Vashishtha and Buddha) ....................................................... 106 Chapter Nine the Tantra Shastras in China................................................................... 113 Chapter Ten A Tibetan Tantra ...................................................................................... 118 Chapter Eleven Shakti in Taoism ................................................................................. 125 Chapter Twelve Alleged Conflict of Shastras............................................................... 130 Chapter Thirteen Sarvanandanatha ............................................................................. -

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’S Vaisnava Theism

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa 1 2 Table of Contents Page No Preface 5 1. Dvaita System of Vedanta 7 2. Conginition 9 Introduction 9 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception 10 Anumana, Inference 12 Sabda, Word Testimony 13 3. Metaphysical Categories 15 General 15 Nature 16 Individual Soul (Jiva) 18 God 20 4. Purusartha, Human Goal 25 Purusartha, Human Goal 25 Sadhana, Means of Attainment 27 5. Evolution of Dvaita Thought 30 6. Madhva Hagiology 33 7. Works of Madhva–Sarvamula 35 An Outline 35 Gita Bhashya 38 Gita Tatparya 40 Sutra –Prasthana 42 General Brahmasutra Bhashya Anu Vyakhyana Nyaya Vivarana Anu Bhashya Bhagavata Tatparya 48 Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya 49 Dasa-Prakaranas 52 Pramanalaksana Kathalaksana Upadhi Khandana Prapanca-Mithyatvanumana Khandana Mayavada Khandana Tattva Samkhyanam Tattva Viveka Tattvoddyota Visnu Tattva Nirnaya Karma Nirnaya Upanisad Bhashyas 59 General 3 Isavasya Upanisad Bhashya Kena or Talavakara Upanisad Bhashya Katha Upanisad Bhashya Mundaka Upanisad Bhashya Prasna Upanisad Bhashya Mandukya Upanisad Bhashya Aitareya Upanisad Bhashya Taittiriya Upanisad Bhashya Brhadaranyaka Upanisad Bhashya Chhandogya Upanisad Bhashya Rigveda Bhashya 66 Stotras, and Works on Worship and Rituals 69 8. Jayatirtha 72 General 72 Works of Jayatirtha 73 9. Visnudasa 76 10. Vyasatirtha 79 General 79 Works of Vyasatirtha 80 11. Other Madhva Pontiffs 84 Vijayendratirtha Vadirajatirtha Narayanacarya Vidyadhirajatirtha Vyasatirtha Vijayadhavajatirtha Sudhindratirtha Vidyadhisatirtha Visvesvaratirtha Raghavendratirtha Brahmanyatirtha and Others 12. Haridasakuta 89 4 Preface Dualism, as understood in western philosophy, is a ‘theory which admits two independent and mutually irreducible substances’. Samkhya Dualism answers to this definition. But Madhva’s Dvaita, Dualism admits two mutually irreducible principles as constituting Reality as a whole, but regards only one of them, God as independent, svatantra and the other as dependent, paratantra. -

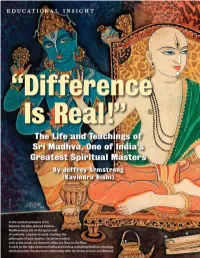

Difference Is Real”

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT The Life and Teachings of Sri Madhva, One of India’s Greatest Spiritual Masters By Jeffrey Armstrong (Kavindra Rishi) s. rajam In the constant presence of his Beloved, the blue-skinned Krishna, Madhvacharya sits on the guru’s seat of authority, scripture in hand, teaching the philosophy of pure dualism. Sectarian symbols, such as the conch, are drawn in white rice fl our on the fl oor. A nitch on the right enshrines Radha and Krishna, indicating Madhva’s theology, which describes the devotee’s relationship with the Divine as lover and Beloved. july/august/september, 2008 hinduism today 39 The Remarkable Life of Sri Madhvacharya icture a man off powerfulf physique, a champion wrestler, who They are not born and do not die, though they may appear to do so. tiny platform,f proclaimedd to the crowdd off devoteesd that Lordd Vayu, Vasudeva was physically and mentally precocious. Once, at the could eat hundreds of bananas in one sitting. Imagine a guru Avatars manifest varying degrees of Divinity, from the perfect, or the closest deva to Vishnu, would soon take birth to revive Hindu age of one, he grabbed hold of the tail of one of the family bulls who P who was observed to lead his students into a river, walk them Purna-Avatars, like Lord Rama and Lord Krishna, to the avatars of dharma. For twelve years, a pious brahmin couple of modest means, was going out to graze in the forest and followed the bull all day long. across the bottom and out the other side. -

The Tantrasara of Abhinava Gupta. Edited with Notes By

THE KASHMIR SERIES OF TEXTS AND STUDIES. c jtvntfi fit ate mid NO. xvn. THE TANTRASARA OF ABHINAVA GUPTA. Edited with notes by MAHAMAHOPADHYAYA PANDIT MUKUND RAM SHASTR1, Offlcer-in-Cliarge Eeseaxcli Department, JAMMU AND KASHMIR STATE, SRINAGAR, Published under the Authority of the Government of His Highness Lieut.-General Maharaja Sir PRATAP SINGH SAHIB BAHADUR, Q. C. S. I., Q. C. I. E., MAHARAJA OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR STATE, BOMBAY: PRINTED AT THE 'NIRNAYA-SAQAR' PRESS, 1918. PK 313/ ft 51 -..- % f 808994 . (All rights reserved). Printed by Ramchandra Yesu Shedge, at the 'Nirnaya-sagar' Press, 23, Kolbhat Lane, Bombay. Published by Mahamahopadhyaya Pandit Mukund Ram Shastri for the Research Department, Jammu and Kashmir State, SR1NAQAR. t i V II ^ II PREFATORY. Before introducing the reader to the most abstruse and technical contents of this philosophical work I take this opportunity to express my heartfelt thanks to the owners of the manuscripts which have been made the main bases of this edition of the Tantrasara, appearing for the first time as volume XVII of the Kashmir Series of Texts and Studies. In all there were three manuscript copies used in preparation of this work for the Press. The first of these belonging to RajanakaSodarshana of Srinagar con- sisted of 72 leaves of Kashmiri paper written in Sharada characters, and of this a copy was made in this office. It is a transcript of another older manuscript and bears 1903 anno Vikrami (1846 A.D.) as the date of its trans- cription. As regards omissions and mistakes it is, how- ever, not free from blemishes.