University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theatre of the Absurd : Its Themes and Form

THE THEATRE OF THE ABSURD: ITS THEMES AND FORM by LETITIA SKINNER DACE A. B., Sweet Briar College, 1963 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Speech KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1967 Approved by: c40teA***u7fQU(( rfi" Major Professor il PREFACE Contemporary dramatic literature is often discussed with the aid of descriptive terms ending in "ism." Anthologies frequently arrange plays under such categories as expressionism, surrealism, realism, and naturalism. Critics use these designations to praise and to condemn, to denote style and to suggest content, to describe a consistent tone in an author's entire ouvre and to dissect diverse tendencies within a single play. Such labels should never be pasted to a play or cemented even to a single scene, since they may thus stifle the creative imagi- nation of the director, actor, or designer, discourage thorough analysis by the thoughtful viewer or reader, and distort the complex impact of the work by suppressing whatever subtleties may seem in conflict with the label. At their worst, these terms confine further investigation of a work of art, or even tempt the critic into a ludicrous attempt to squeeze and squash a rounded play into a square pigeon-hole. But, at their best, such terms help to elucidate theme and illuminate style. Recently the theatre public's attention has been called to a group of avant - garde plays whose philosophical propensities and dramatic conventions have been subsumed under the title "theatre of the absurd." This label describes the profoundly pessimistic world view of play- wrights whose work is frequently hilarious theatre, but who appear to despair at the futility and irrationality of life and the inevitability of death. -

A View of Rebellion and Humanism in Albert Camus’ The

A VIEW OF REBELLION AND HUMANISM IN ALBERT CAMUS’ THE PLAGUE THESIS Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Sarjana Degree of English Department Faculty of Arts and Humanities State Islamic University of Sunan Ampel Surabaya By: Siti Nur Aviva Reg. Number: A33213075 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SUNAN AMPEL SURABAYA 2018 ABSTRACT Aviva, Siti Nur. 2018. A View of Rebellion and Humanism in Albert Camus’ The Plague. English Department, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, State Iislamic Uinversity (UIN) Sunan Ampel Surabaya. Advisor: Dr. Mohammad Kurjum, M. Ag. This thesis analyzes a philosophical novel written by the French-Algerian author namely Albert Camus, The Plague. The purpose of this thesis is to interpret an opposition in The Plague novel and with the proposition of Albert Camus's philosophical book The Rebel. This thesis uses descriptive analysis method. In that method, the first is reading novel stories. The two is collecting important sections dealing with the issues contained in The Rebel's book. The third is interpreting, which uses the hermeneutic theory of Hans-George Gadamer. The Fourth is ending with a conclusion. The results of this interpretation are; (1) the main character as a measure of rebellion; (2) a plague metaphor which means a symbol of human lust. Through the image of the citizens of Oran, human desires are seen where the state of calm, they do the habit of seeking comfort and security by searching for materialistic life, suddenly become chaotic because of epidemic; (3) humanism is a rebellious human who always appreciates life and has a noble value; (4) The rebellion is divided into two: physical rebellion and metaphysical rebellion. -

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Stefka G Mihaylova Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Drama © Copyright 2013 Sarah Guthu University of Washington Abstract European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Thomas E Postlewait School of Drama This dissertation offers a cultural history of the arrival of the second wave of European modernist drama in America in the postwar period, 1950-1970. European modernist drama developed in two qualitatively distinct stages, and these two stages subsequently arrived in the United States in two distinct waves. The first stage of European modernist drama, characterized predominantly by the genres of naturalism and realism, emerged in Europe during the four decades from the 1890s to the 1920s. This first wave of European modernism reached the United States in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, coming to prominence through productions in New York City. The second stage of European modernism dates from 1930 through the 1960s and is characterized predominantly by the absurdist and epic genres. Unlike the first wave, the dramas of the second wave of European modernism were not first produced in New York. Instead, these plays were often given their premieres in smaller cities across the United States: San Francisco, Seattle, Cleveland, Hartford, Boston, and New Haven, in the regional theatres which were rapidly proliferating across the United States. -

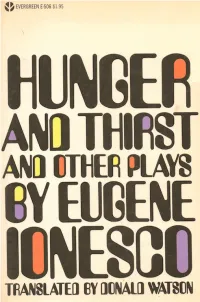

Hunger and Thirst & Other Plays

Hunger and Thirst and Other Plays Other Works by Eugene Ionesco Amedee, The New Tenant, Victims of Duty The Bald Soprano Exit the King Fragments of a journal Four Plays The Killer and Other Plays Notes and Counter Notes Rhinoceros and Other Plays A Stroll in the Air, Frenzy for Two, or More Eugene Ionesco HUNGER AND THIRST and other plays Translated from the French by Donald Watson GI�OVE PI�ESS, II\:C. :'\E\\' YOI�K Theu trar1slatio11S CO/J)' Tighted © 1968 In• Calder all(/ Royars, Ltd. Hrm{!.n a11d Thirst was originally published as La Soif et la Faim ropnigiH ® •!)fiG hl· Editions Galliman!. Paris. The Pic· ttne, Auger, and Salutations were originally publishf'd as Le Tableau, /.a Co/he, Les .\alutatiom copyright © 1!)63 by Edi· tions l.allimarcl, Paris All R ights Resewed l.ibrary of Co11g1·e.u Catalog Card Number: 73-79095 First Printing, 1969 CAl;rJO)';:h T rse plays are full)' protected, in whole, in part or iu any form uuder the copyright laws of thl' United States of America, the Rritis/1 Empire including the Dominion of Can ada, a11d all other countries of the Cop)'right Union, and are sul>ject to royalty. All rights, incl11ding professional, amateur, motion picture, radio, teler>ision, recitation, public rradillfi, and all\' m eth od of photographic reproduction, are strictly resenwl. For /JTOfessiorral rightl all inquiries should l>e addre.Hed to !.rope Prrss, Inc., Ro Unir>ersity Place, New York, X.l'. 1ooo;. For amateur and stock rights all inquiries should be adrlre.«ed to Samuel French, Inc., 25 West 45th Street, Xew York, .V.Y. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A comedy of anguish: a study of the plays of Eugene Ionesco Stokes, William Philip Harvey How to cite: Stokes, William Philip Harvey (1978) A comedy of anguish: a study of the plays of Eugene Ionesco, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10176/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT A Comedy of Anguish; A Study of the Plavs of Eugene lonescG "by W.P.H. Stokes The antithetical title A Comedy of Anguish has been selected to represent the ironic manner and tone in which lonesco has sought. •b« release from his subconscious fears, fears common to humanity in every age. His uimitigated anguish serves as a reminder of the consequences of that scientific discovery, made long before Nietzsche's cry "God is dead", that we are confined to the limits of time and hence desperately need to relate to a substitute for the Almighty, beyond those limits. -

Of Plagues and Nazis: Camus' Journey from Moral Nihilism

The Journal of Social Encounters Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 10 2020 Rereading Albert Camus’ The Plague During a Pandemic: Of Plagues and Nazis: Camus’ Journey from Moral Nihilism Stephen I. Wagner College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Philosophy Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wagner, Stephen I. (2020) "Rereading Albert Camus’ The Plague During a Pandemic: Of Plagues and Nazis: Camus’ Journey from Moral Nihilism," The Journal of Social Encounters: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, 103-106. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters/vol4/iss2/10 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Social Encounters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Journal of Social Encounters Rereading Albert Camus’ The Plague During a Pandemic: Of Plagues and Nazis: Camus’ Journey from Moral Nihilism Stephen I. Wagner College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University During our current pandemic, Albert Camus’ novel, The Plague, can serve readers well by illustrating and perhaps helping us resolve the feelings, options and decisions we are now facing. Indeed, Camus can help us learn much from our current situation. Camus’ plague takes place in Oran, an Algerian city under the control of France. -

Medicine As Absurdity in Albert Camus' “The Plague”

Medicine as an Absurdist Quest in Albert Camus’ The Plague Robert J. Bonk Widener University [email protected] · www2.widener.edu/~rjbonk/ Abstract: As a social construct, modern medicine reflects a society’s paradigms and perspectives. Within a modern technological age of increasing estrangement, intellectuals developed new philosophies such as absurdism—as well as literature reflecting these paradigms—that soon questioned whether a “magic bullet” could ever offer a panacea for antiseptic institutions. One exemplar is French-Algerian writer Albert Camus. In his 1947 novel The Plague, Camus quarantines the inhabitants of Oran in a struggle against a bubonic-like epidemic. Within this microcosm, Camus juxtaposes medicine against government and religion in his quest to find medical meaning in an absurd world. Keywords: absurdity, Albert Camus, existentialism, medicine, plague Resumen: La medicina como una búsqueda absurdista en La Plaga de Albert Camus Como construcción social, la medicina moderna refleja los paradigmas y las perspectivas de una sociedad. Dentro de una era moderna y tecnológica de 1 creciente enajenación, los intelectuales desarrollaron nuevas filosofías tales como el absurdismo —así como también una literatura que refleja esos paradigmas— que rápidamente se cuestionó si “una bala mágica” alguna vez ofrecería una panacea para las instituciones antisépticas. Un modelo es el del escritor franco-argelino Albert Camus, que en su novela La Peste (1947), pone en cuarentena a los habitantes de Orán en la lucha contra una epidemia como la peste bubónica. Dentro de este microcosmos, Camus yuxtapone la medicina contra gobierno y religión en su búsqueda del sentido médico en un mundo absurdo. -

T.R. Suleyman Demirel University Institute of Social Sciences Department of Western Languages and Literature English Language and Literature

T.R. SULEYMAN DEMIREL UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF WESTERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL SATIRE IN SELECTED PLAYS OF JOHN OSBORNE Ph.D. Thesis Abdul Aljaleel Fadhıl Jamaıl AL-JAMAIL 1340224505 Supervisor Prof. Dr. Ömer ŞEKERCİ ISPARTA-2019 T.C. SÜLEYMAN DEMİREL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ BATI DİLLERİ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI BİLİM DALI JOHN OSBORNE'UN SEÇİLMİŞ OYUNLARINDAKİ SOSYAL VE POLİTİK HİCİV DOKTORA TEZİ Abdul Aljaleel Fadhıl Jamaıl AL-JAMAIL 1340224505 Danışman Prof. Dr. Ömer ŞEKERCİ ISPARTA-2019 (AL-JAMAIL, Abdul Aljaleel Fadhıl Jamaıl, Social and Political Satire in Selected Plays of John Osborne, Ph.D Thesis, Isparta, 2019) ABSTRACT The core of this study is an enquiry into the rebel hero as reflected in the selected plays by John Osborne. It tries to discuss the dramatic climate in England in the aftermath of the Second World War, with special concentration on the factors influencing upon and leading to the emergence of the new English drama in the late fifties. The chapter deals with a brief analysis of the “Angry Young Men Movement” and the rebel or outsider figure in post-war English literature in terms of studying the different theories concerning his origin characteristics and the various causes motivating him to rebellion. The study attempts to investigate the rebel hero in Osborne's plays Look Back in Anger (1956), The Entertainer (1957), and Luther (1961) respectively The subject is pursued by investigating the various social, political, economic, and psychological causes inducing the main character in these texts to adopt a rebellious stance, the targets as well as the alternatives which Osborne's rebel sees as possible solutions to his problems. -

Albert Camus' Presentation of Absurdism As a Foundation for Goodness

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Meaningful Meaninglessness: Albert Camus' Presentation of Absurdism as a Foundation for Goodness Maria K. Genovese Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Genovese, Maria K., "Meaningful Meaninglessness: Albert Camus' Presentation of Absurdism as a Foundation for Goodness" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 60. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/60 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genovese 1 In 1957, Albert Camus won the Nobel Prize for Literature. By that time he had written such magnificently important works such as Caligula (1938), The Stranger (1942), The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), The Plague (1947), The Rebel (1951), and The Fall (1956). Camus was a proponent of Absurdism, a philosophy that realizes the workings of the world are inherently meaningless and indifferent to the human struggle to create meaning. Absurdism, however, is not a nihilistic philosophy. In The Myth of Sisyphus , The Rebel , and Caligula , Camus offers a foundation of optimism and morality. Albert Camus was born in Algeria on November 7, 1913. His father was killed in World War I in 1914. In 1930, Camus was diagnosed with tuberculosis, thus ending his football (soccer) career and forcing him to complete his studies part-time. -

The Catastrophic Theatre Presents Eugene Ionesco's Absurdist Classic

October 23, 2017 For immediate release Contact: Shayna Schlosberg Managing Director [email protected] 713-522-2723x3 The Catastrophic Theatre Presents Eugene Ionesco’s Absurdist Classic, Rhinoceros The Catastrophic Theatre continues its tradition of presenting avant-garde classics with Eugene Ionesco’s anti-fascist comeDy RHINOCEROS (Houston, TX) RegarDeD as one of the lanDmark plays of the 20th century, RHINOCEROS is a moDern masterpiece that comments on the plight of the human conDition, maDe tolerable only by self-delusion. The proDuction begins November 17 anD runs through December 10. Tickets are on sale now anD can be purchaseD at matchouston.org or by calling the Box Office at 713-521-4533. Performances are Thursdays at 7:30 p.m., Fridays anD Saturdays at 8:00 p.m., anD SunDays at 2:30 p.m. A rhinoceros suDDenly appears in a sleepy town, trampling through the peaceful streets. Soon another appears, anD another, anD another until it becomes clear that orDinary citizens are actually transforming into beasts as they learn to “move with the times.” Martin Esslin, author of the classic book THE THEATRE OF THE ABSURD, notes that “what the play conveys is the absurDity of Defiance as much as the absurDity of conformism, the trageDy of the inDiviDualist who cannot join the happy throng of less sensitive people, the artist’s feelings as an outcast…” Full of biting wit anD nightmarish anxiety, RHINOCEROS is Eugene Ionesco’s most famous play. Ionesco fleD Rumania in 1938, as more anD more of his acquaintances began to aDhere to the fascist Iron GuarD. -

Proquest Dissertations

"The Plague" in Albert Camus's fiction Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Ast, Bernard Edward Jr., 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 14:03:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288839 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the origmal or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized cop3^ght material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Functions of Intermediality in the Simpsons

Functions of Intertextuality and Intermediality in The Simpsons Der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) eingereichte Dissertation von Wanja Matthias Freiherr von der Goltz Datum der Disputation: 05. Juli 2011 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Josef Raab Prof. Dr. Jens Gurr Table of Contents List of Figures...................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 5 1.1 The Simpsons: Postmodern Entertainment across Generations ................ 5 1.2 Research Focus .............................................................................................11 1.3 Choice of Material ..........................................................................................16 1.4 Current State of Research .............................................................................21 2. Text-Text Relations in Television Programs ....................................... 39 2.1 Poststructural Intertextuality: Bakhtin, Kristeva, Barthes, Bloom, Riffaterre .........................................................................................................39 2.2 Forms and Functions of Intertextual References ........................................48 2.3 Intertextuality and Intermediality ..................................................................64 2.4 Television as a