360 ° Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroes / Low Symphonies Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bowie Heroes / Low Symphonies mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Heroes / Low Symphonies Country: Europe Released: 2003 Style: Contemporary MP3 version RAR size: 1762 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1736 mb WMA version RAR size: 1677 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 492 Other Formats: VQF AUD WAV MP4 FLAC ADX DMF Tracklist Heroes Symphony 1-1 Heroes 5:53 1-2 Abdulmajid 8:53 1-3 Sense Of Doubt 7:21 1-4 Sons Of The Silent Age 8:19 1-5 Neuköln 6:44 1-6 V2 Schneider 6:49 Low Symphony 2-1 Subterraneans 15:11 2-2 Some Are 11:20 2-3 Warszawa 16:01 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Decca Music Group Limited Copyright (c) – Decca Music Group Limited Record Company – Universal Music Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal International Music B.V. Credits Composed By – Philip Glass Conductor [Associate Conductor] – Michael Riesman (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6) Conductor [Principal] – Dennis Russell Davies Engineer – Dante DeSole (tracks: 2-1 to 2-3), Rich Costey (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6) Executive-Producer – Kurt Munkacsi, Philip Glass, Rory Johnston Music By [From The Music By] – Brian Eno, David Bowie Orchestra – American Composers Orchestra (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6), The Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra Producer – Kurt Munkacsi, Michael Riesman Producer [Associate] – Stephan Farber (tracks: 1-1 to 1-6) Notes This compilation ℗ 2003 Decca Music Group Limited © 2003 Decca Music Group Limited CD 1 ℗ 1997 Universal International Music BV CD 2 ℗ 1993 Universal International Music BV Artists listed as: Bowie & Eno meet Glass on spine; Glass Bowie Eno on front cover; Bowie Eno Glass on both discs. -

Masayoshi Sukita “40Th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes”

Masayoshi Sukita “40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes” 12. Mai – 12. August 2017 Heroes © 1977 / 1997 Risky Folio, Inc. Courtesy of The David Bowie Archive ™ Preisliste / Pricelist All pictures of the exhibition are titled and signed on the back including local sales tax (19%). galerie hiltawsky Tucholskystraße 41, 10117 Berlin +49 (0)30 285 044 99 | (0)171 81 34 567 Di – Sa 14 – 19 Uhr u.n.V. Masayoshi Sukita 40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes 12. Mai – 12. August 2017 Preisliste / Pricelist 01. Masayoshi Sukita, "Heroes" To Come, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 50,8 cm x 40,6 cm, Edition 10/30, € 1.950 02. Masayoshi Sukita, MY-MY / MY-MY, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 4/30, € 1.950 03. Masayoshi Sukita, 1977 n°1, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 76,2 cm x 101,6 cm, Edition 1/10, € 3.900 Masayoshi Sukita 40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes 12. Mai – 12. August 2017 Preisliste / Pricelist 04. Masayoshi Sukita, 1977 n°2, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 1/30, € 1.950 05. Masayoshi Sukita, "Heroes", Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 18/30, € 29.000 (one of the last 2 available !) 06. Masayoshi Sukita, 1977 n°3, Japan, 1977 Lambda print on Fuji photographic paper 40,6 cm x 50,8 cm, Edition 1/30, € 1.950 Masayoshi Sukita 40th Anniversary of David Bowie's Heroes 12. -

My Back Pages #1

My Back Pages #1 L’iMMaginario coLLettivo deL rock neLLe fotografie di Ed CaraEff, HEnry diltz, HErb GrEEnE, Guido Harari, art KanE, astrid KirCHHErr, Jim marsHall, norman sEEff e bob sEidEmann 04.02 | 11.03.2012 Wall of sound gallery La capsula del tempo decolla… La musica non è solo suono, ma anche immagine. Senza le visioni di questi fotografi, non avremmo occhi per guardare la musica. Si può ascoltare e “ca- pire” Jimi Hendrix senza vedere la sua Stratocaster in fiamme sul palco di Monterey, fissata per sempre da Ed Caraeff? O intuire fino in fondo la deriva amara di Janis Joplin senza il crudo bianco e nero di Jim Marshall che ce la mostra affranta con l’inseparabile bottiglia di Southern Comfort in mano? Nasce così l’immaginario collettivo del rock, legato anche a centinaia di co- pertine di dischi. In questa mostra sfilano almeno una dozzina di classici: dagli album d’esordio di Crosby Stills & Nash e di Stephen Stills in solitario a Morrison Hotel dei Doors, The Kids Are Alright degli Who, al primo disco americano dei Beatles per l’etichetta VeeJay, Hejira di Joni Mitchell, Surre- alistic Pillow dei Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead di Jerry Garcia e compa- gni, Genius Loves Company di Ray Charles, Stage Fright della Band di Robbie Robertson, Desperado degli Eagles e Hotter Than Hell dei Kiss. Il tempismo è tutto. Soprattutto trovarsi come per miracolo all’inizio di qualcosa, ad una magica intersezione col destino che può cambiare la vita di entrambi, fotografo e fotografato. Questo è successo ad astrid Kirchherr con i Beatles ancora giovanissimi ad Amburgo, o a Herb Greene immerso nella ribollente “scena” musicale di San Francisco. -

Romania's Cultural Wars: Intellectual Debates About the Recent Past

ROMANIA'S CULTURAL WARS : Intellectual Debates about the Recent Past Irina Livezeanu University of Pittsburgh The National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h 910 17`" Street, N.W . Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 2000 6 TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Contractor : University of Pittsburgh Principal Investigator: Irina Livezeanu Council Contract Number : 816-08 Date : March 27, 2003 Copyright Informatio n Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funde d through a contract or grant from the National Council for Eurasian and East European Researc h (NCEEER). However, the NCEEER and the United States Government have the right to duplicat e and disseminate, in written and electronic form, reports submitted to NCEEER to fulfill Contract o r Grant Agreements either (a) for NCEEER's own internal use, or (b) for use by the United States Government, and as follows : (1) for further dissemination to domestic, international, and foreign governments, entities and/or individuals to serve official United States Government purposes or (2) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of th e United States Government granting the public access to documents held by the United State s Government. Neither NCEEER nor the United States Government nor any recipient of this Report may use it for commercial sale . * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by th e National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available b y the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Trainin g Act of 1983, as amended) . -

Eugene Ionesco and the Absurdist Theatre

Eugene Ionesco and the Absurdist Theatre April 6, 2016 à The Theatre of the Absurd – Expression popularized by Martin Esslin in 1961 à Expression of the absurdity of life – Each play is a theatrical metaphor for the absurdity of life; à Metaphor – alternately comic and tragic, usually symbolic and always unusual and bizarre à Beyond illogical dialogue or stage business: - the absurd often implies an ahistorical, non-dialectical dramaturgical structure. - Man is a timeless abstraction incapable of finding a foothold in his frantic search for a meaning that constantly eludes him. - His actions have neither meaning nor direction; the fabula of absurd is often circular, guided not by dramatic action but by wordplay and a search for words. Relevant Information Origins of Absurdism: 19th century in the work of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813 – 1855). He developed and wrote about his own existential philosophy based around Christianity and addressed the nature in which humans confront absurdity. Absurdism: humans historically attempt to find meaning in their lives. This search results in one of two conclusions: - Either that life is meaningless - Or life contains within it a purpose set forth by a higher power—a belief in God, or adherence to some religion or other abstract concept. Kierkegaard describes how such a man would endure such a defiance and identifies the three major traits of the Absurd Man, later discussed by Albert Camus: - A rejection of escaping existence (suicide) - A rejection of help from a higher power - -

CHILLED CAVIAR to EAT... a Little More Naked... VEGETABLES and MORE... FLOUR and WATER

CHILLED VEGETABLES AND MORE... TO EAT... (V) Garden Vegetable Crudités 18 (V) Coleman Farm's Garden Green Salad 22 • (VG) Austrian White Asparagus 32 Santa Monica Farmers' Market Seasonal Harvest Heirloom Lettuces, Spring Citrus, Meyer Lemon Vinaigrette Sun-Dried Tomato Chimichurri, Marinated Quinoa and Spring Vegetables, Sunflower Seeds Cilantro Green Goddess Dressing Toasted Black Olive Crostini with Local Goat Cheese Alaskin Halibut 49* Baja Gulf Prawns 36 (V) Imported Italian Burrata 18 Pan-Roasted, Braised Baby Artichokes, Confit Fennel, Lemon Purée, Herb Gremolata Spicy Horseradish, Citrus Tomato Sauce 18-Year Aged Balsamic Vinegar, Grilled Country White Bread Toasted Pepitas, Foraged Herbs • Organic Jidori Half Chicken 54 Whole Santa Barbara Uni 24* Porcini Mushrooms, Romano Beans, Natural Jus Tomato, Red Onion, Micro Shiso (V) Caramelized Corn Salad 24 First of the Season White Corn, Frijoles, Cherry Tomatoes • 8oz USDA Prime 'Butcher's Butter' 76* Kusshi Oysters 24/48* Wild Arugula, Cilantro Crema, Black Lime Vinaigrette Pommes Aligot, Sauce Armagnac British Columbia, Clean, Mildly Sweet, Slightly Meaty Green Apple Fennel-Mignonette (V) Green Asparagus Soup 22 (WP) Marcho Farms Veal 'Wiener Schnitzel' 49* White Asparagus, Meyer Lemon Oil Marinated Fingerling Potatoes, Marinated Cherry Tomatoes, Styrian Pumpkin Seed Oil Omega Blue Kanpachi Tataki Crudo 32* Carrot Aguachile, Pickled Green Almonds, Charred Scallion • CAB 'Never Ever' Beef Burger 28* Japanese Cucumber, Avocado, Coriander FLOUR AND WATER Vermont White Cheddar, Garlic -

Theatre of the Absurd : Its Themes and Form

THE THEATRE OF THE ABSURD: ITS THEMES AND FORM by LETITIA SKINNER DACE A. B., Sweet Briar College, 1963 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Speech KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1967 Approved by: c40teA***u7fQU(( rfi" Major Professor il PREFACE Contemporary dramatic literature is often discussed with the aid of descriptive terms ending in "ism." Anthologies frequently arrange plays under such categories as expressionism, surrealism, realism, and naturalism. Critics use these designations to praise and to condemn, to denote style and to suggest content, to describe a consistent tone in an author's entire ouvre and to dissect diverse tendencies within a single play. Such labels should never be pasted to a play or cemented even to a single scene, since they may thus stifle the creative imagi- nation of the director, actor, or designer, discourage thorough analysis by the thoughtful viewer or reader, and distort the complex impact of the work by suppressing whatever subtleties may seem in conflict with the label. At their worst, these terms confine further investigation of a work of art, or even tempt the critic into a ludicrous attempt to squeeze and squash a rounded play into a square pigeon-hole. But, at their best, such terms help to elucidate theme and illuminate style. Recently the theatre public's attention has been called to a group of avant - garde plays whose philosophical propensities and dramatic conventions have been subsumed under the title "theatre of the absurd." This label describes the profoundly pessimistic world view of play- wrights whose work is frequently hilarious theatre, but who appear to despair at the futility and irrationality of life and the inevitability of death. -

The Jamison Galleries Collection

THE JAMISON GALLERIES COLLECTION BETTY W. AND ZEB B. CONLEY PAPERS New Mexico Museum of Art Library and Archives Dates: 1950 - 1995 Extent: 7.33 linear feet Contents Part One. Materials on Artists and Sculptors Part Two. Photographs of Works Part Three. Additional Material Revised 01/11/2018 Preliminary Comments The Jamison Galleries [hereafter referred to simply as “the Gallery”] were located on East Palace Avenue, Santa Fe, from August 1964 until January 1993, at which time it was moved to Montezuma Street. There it remained until December 1997, when it closed its doors forever. Originally owned by Margaret Jamison, it was sold by her in 1974 to Betty W. and Zeb B. Conley. The Library of the Museum of Fine Arts is indebted to the couple for the donation of this Collection. A similar collection was acquired earlier by the Library of the records of the Contemporaries Gallery. Some of the artists who exhibited their works at this Gallery also showed at The Contemporaries Gallery. Included in the works described in this collection are those of several artists whose main material is indexed in their own Collections. This collection deals with the works of a vast array of talented artists and sculptors; and together with The Contemporaries Gallery Collection, they comprise a definitive representation of southwestern art of the late 20th Century. Part One contains 207 numbered Folders. Because the contents of some are too voluminous to be limited to one folder, they have been split into lettered sub-Folders [viz. Folder 79-A, 79-B, etc.]. Each numbered Folder contains material relating to a single artist or sculptor, all arranged — and numbered — alphabetically. -

Equity Magazine Autumn 2020 in This Issue

www.equity.org.uk AUTUMN 2020 Filming resumes HE’S in Albert Square Union leads the BEHIND fight for the circus ...THE Goodbye, MASK! Christine Payne Staying safe at the panto parade FIRST SET VISITS SINCE THE LIVE PERFORMANCE TASK FORCE FOR COVID PANDEMIC BEGAN IN THE ZOOM AGE FREELANCERS LAUNCHED INSURANCE? EQUITY MAGAZINE AUTUMN 2020 IN THIS ISSUE 4 UPFRONT Exclusive Professional Property Cover for New General Secretary Paul Fleming talks Panto Equity members Parade, equality and his vision for the union 6 CIRCUS RETURNS Equity’s campaign for clarity and parity for the UK/Europe or Worldwide circus cameras and ancillary equipment, PA, sound ,lighting, and mechanical effects equipment, portable computer 6 equipment, rigging equipment, tools, props, sets and costumes, musical instruments, make up and prosthetics. 9 FILMING RETURNS Tanya Franks on the socially distanced EastEnders set 24 GET AN INSURANCE QUOTE AT FIRSTACTINSURANCE.CO.UK 11 MEETING THE MEMBERS Tel 020 8686 5050 Equity’s Marlene Curran goes on the union’s first cast visits since March First Act Insurance* is the preferred insurance intermediary to *First Act Insurance is a trading name of Hencilla Canworth Ltd Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under reference number 226263 12 SAFETY ON STAGE New musical Sleepless adapts to the demands of live performance during the pandemic First Act Insurance presents... 14 ONLINE PERFORMANCE Lessons learned from a theatre company’s experiments working over Zoom 17 CONTRACTS Equity reaches new temporary variation for directors, designers and choreographers 18 MOVEMENT DIRECTORS Association launches to secure movement directors recognition within the industry 20 FREELANCERS Participants in the Freelance Task Force share their experiences Key features include 24 CHRISTINE RETIRES • Competitive online quote and buy cover provided by HISCOX. -

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Stefka G Mihaylova Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Drama © Copyright 2013 Sarah Guthu University of Washington Abstract European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Thomas E Postlewait School of Drama This dissertation offers a cultural history of the arrival of the second wave of European modernist drama in America in the postwar period, 1950-1970. European modernist drama developed in two qualitatively distinct stages, and these two stages subsequently arrived in the United States in two distinct waves. The first stage of European modernist drama, characterized predominantly by the genres of naturalism and realism, emerged in Europe during the four decades from the 1890s to the 1920s. This first wave of European modernism reached the United States in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, coming to prominence through productions in New York City. The second stage of European modernism dates from 1930 through the 1960s and is characterized predominantly by the absurdist and epic genres. Unlike the first wave, the dramas of the second wave of European modernism were not first produced in New York. Instead, these plays were often given their premieres in smaller cities across the United States: San Francisco, Seattle, Cleveland, Hartford, Boston, and New Haven, in the regional theatres which were rapidly proliferating across the United States. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

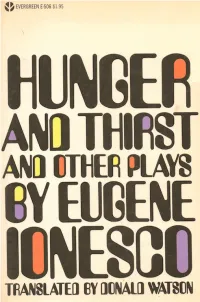

Hunger and Thirst & Other Plays

Hunger and Thirst and Other Plays Other Works by Eugene Ionesco Amedee, The New Tenant, Victims of Duty The Bald Soprano Exit the King Fragments of a journal Four Plays The Killer and Other Plays Notes and Counter Notes Rhinoceros and Other Plays A Stroll in the Air, Frenzy for Two, or More Eugene Ionesco HUNGER AND THIRST and other plays Translated from the French by Donald Watson GI�OVE PI�ESS, II\:C. :'\E\\' YOI�K Theu trar1slatio11S CO/J)' Tighted © 1968 In• Calder all(/ Royars, Ltd. Hrm{!.n a11d Thirst was originally published as La Soif et la Faim ropnigiH ® •!)fiG hl· Editions Galliman!. Paris. The Pic· ttne, Auger, and Salutations were originally publishf'd as Le Tableau, /.a Co/he, Les .\alutatiom copyright © 1!)63 by Edi· tions l.allimarcl, Paris All R ights Resewed l.ibrary of Co11g1·e.u Catalog Card Number: 73-79095 First Printing, 1969 CAl;rJO)';:h T rse plays are full)' protected, in whole, in part or iu any form uuder the copyright laws of thl' United States of America, the Rritis/1 Empire including the Dominion of Can ada, a11d all other countries of the Cop)'right Union, and are sul>ject to royalty. All rights, incl11ding professional, amateur, motion picture, radio, teler>ision, recitation, public rradillfi, and all\' m eth od of photographic reproduction, are strictly resenwl. For /JTOfessiorral rightl all inquiries should l>e addre.Hed to !.rope Prrss, Inc., Ro Unir>ersity Place, New York, X.l'. 1ooo;. For amateur and stock rights all inquiries should be adrlre.«ed to Samuel French, Inc., 25 West 45th Street, Xew York, .V.Y.