THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security and Diplomacy in the Western Balkans

IFIMES Milan Jazbec SECURITY AND DIPLOMACY IN THE WESTERN BALKANS SECURITY AND DIPLOMACY SECURITY AND DIPLOMACY IN THE WESTERN BALKANS ISBN 978-961-238-899-7 Milan Jazbec SECURITY AND DIPLOMACY IN THE WESTERN BALKANS MILAN JAZBEC IFIMES LJUBLJANA, 2007 This publication was sponsored by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ljubljana and by the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Ljubljana, both on behalf of their respected countries. The list of the Slovene and other sponsors is enclosed. SECURITY AND DIPLOMACY IN THE WESTERN BALKANS - The Experience of a Small State and Its Diplomat - A Selection of Papers (2000 – 2006) Milan Jazbec IFIMES The International Institute for Middle East and Balkans Studies Ljubljana, 2007 From the Same Author: Konzularni odnosi (Consular Relations) 1997, Ljubljana: FDV www.fdv.zalozba.si Diplomacija in Slovenci (ur.) (Diplomacy and the Slovenes /ed./) 1998, Celovec: Založba Drava www.drava.at Slovenec v Beogradu (A Slovene in Belgrad – a collection of essays) 1999, Pohanca: self published, first edition The Diplomacies of New Small States: The Case of Slovenia with some comparison from the Baltics 2001, Aldershot: Ashgate www.ashgate.com Diplomacija in varnost (Diplomacy and Security) 2002, Ljubljana: Vitrum Mavrica izza duše (The Rainbow Beyond the Soul – novel on diplomacy, first part of the trilogy) 2006, Gorjuša: Miš www.zalozbamish.com Ein Slowene in Belgrad (A Slovene in Belgrad – translation in German) 2006, Celovec: Mohorjeva založba www.hermagoras.at Slovenec v Beogradu (A Slovene -

Slovenija in Nato – Dolga in Vijugasta Pot Slovenia and Nato - the Long and Winding Road

DOI:10.33179/BSV.99.SVI.11.CMC.16.3.2 Milan Jazbec SLOVENIJA IN NATO – DOLGA IN VIJUGASTA POT SLOVENIA AND NATO - THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD Povzetek Prispevek obravnava proces vključevanja Slovenije v Nato, predvsem v letih 2000– 2004. Avtor ga razume v okviru širših sprememb, ki so se zgodile ob koncu hladne vojne, in kot del evropskega integracijskega procesa. Slovenija je bila edina država v širši regiji, ki je postala članica Nata in EU leta 2004, proces pa je trajal dobro desetletje. Za slovenski obrambno-varnostni sistem in za varnost države je bil to najpomembnejši dosežek po osamosvojitvi. Članstvo v Natu je okrepilo slovensko obrambo in vojaško identiteto ter pospešilo različne transformacijske procese, ki so potekali v Slovenski vojski, na primer profesionalizacijo, namestljivost in modernizacijo. Prav tako je oblikovalo razumevanje dejstva, da so vojaške sile orodje zunanje politike in da sta se temeljna zunanjepolitična cilja države (članstvo v Natu in EU) po uresničitvi spremenila v sredstvo za dosego novih ciljev. Leto 2004 predstavlja vrh integracijske dinamike, ki je spremenila evro-atlantski prostor. To je bilo leto stabilizacije, ki je bila dosežena s t. i. velikim širitvenim pokom. Nekatera spoznanja iz Natovih širitev po koncu hladne vojne niso bila razumljena na Zahodnem Balkanu, kar je vplivalo na zastoj širitvenega procesa. Po širitvi 2004 pa je postala integracijska dinamika v tej regiji vsakdanja, tako je območje dobilo prvič v zgodovini edinstveno priložnost za stabilizacijo. Tudi Slovenija je posredovala svoje širitvene izkušnje državam v regiji. Avtor poleg tega predstavlja še nekatere osebne izkušnje, ki pripomorejo k prikazu posebnosti slovenskega članstva v Natu. -

Europe's Coherence Gap in External Crisis and Conflict Management

Bertelsmann Stiftung (ed.) Europe’s Coherence Gap in External Crisis and Conflict Management Political Rhetoric and Institutional Practices in the EU and Its Member States Bertelsmann Stiftung (ed.) Europe’s Coherence Gap in External Crisis and Conflict Management Political Rhetoric and Institutional Practices in the EU and Its Member States Autoren: Prof. Dr. Klaus Siebenhaar Achim Müller Institut für Kultur und Medienwirtschaft Mit einem Begleittext von Jürgen Kesting Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, Guetersloh Responsible: Stefani Weiss Copy editor: Josh Ward Production editor: Christiane Raffel Cover design: Elisabeth Menke Cover illustration: © Shutterstock/Thomas Dutour Illustration pp. 372, 376, 377: Dieter Dollacker Typesetting: Katrin Berkenkamp Printing: Hans Gieselmann Druck und Medienhaus GmbH & Co. KG, Bielefeld ISBN 978-3-86793-911-9 (print) ISBN 978-3-86793-912-6 (e-book PDF) ISBN 978-3-86793-913-3 (e-book EPUB) www.bertelsmann-stiftung.org/publications Contents Introduction ..........................................................7 Reports EU ................................................................... 18 Austria .............................................................. 42 Belgium ............................................................. 57 Bulgaria ............................................................ -

Shelter from the Holocaust

Shelter from the Holocaust Shelter from the Holocaust Rethinking Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union Edited by Mark Edele, Sheila Fitzpatrick, and Atina Grossmann Wayne State University Press | Detroit © 2017 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of Amer i ca. ISBN 978-0-8143-4440-8 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-8143-4267-1 (paper) ISBN 978-0-8143-4268-8 (ebook) Library of Congress Control Number: 2017953296 Wayne State University Press Leonard N. Simons Building 4809 Woodward Ave nue Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309 Visit us online at wsupress . wayne . edu Maps by Cartolab. Index by Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd. Contents Maps vii Introduction: Shelter from the Holocaust: Rethinking Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union 1 mark edele, sheila fitzpatrick, john goldlust, and atina grossmann 1. A Dif er ent Silence: The Survival of More than 200,000 Polish Jews in the Soviet Union during World War II as a Case Study in Cultural Amnesia 29 john goldlust 2. Saved by Stalin? Trajectories and Numbers of Polish Jews in the Soviet Second World War 95 mark edele and wanda warlik 3. Annexation, Evacuation, and Antisemitism in the Soviet Union, 1939–1946 133 sheila fitzpatrick 4. Fraught Friendships: Soviet Jews and Polish Jews on the Soviet Home Front 161 natalie belsky 5. Jewish Refugees in Soviet Central Asia, Iran, and India: Lost Memories of Displacement, Trauma, and Rescue 185 atina grossmann v COntents 6. Identity Profusions: Bio- Historical Journeys from “Polish Jew” / “Jewish Pole” through “Soviet Citizen” to “Holocaust Survivor” 219 john goldlust 7. -

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol. XXI, No. 2 April 2001 One Great Thing Archilochus Madeleine Korbel Albright, during whose tenure as the United States Secretary of State three countries of East Central Europe were admitted to NATO. Photo courtesy of the U. S. State Department. 778 THE SARMATIAN REVIEW April 2001 The Sarmatian Review (ISSN 1059- independent research. The USA, which 5872) is a triannual publication of the Polish In- From the Editor leads the world in research, has never had stitute of Houston. The journal deals with Polish, the habilitacja. Central, and Eastern European affairs, and their Our cover page photo is of Madeleine implications for the United States. We specialize On 26 February 2001 in The Wall Street in the translation of documents. Albright to whom thanks are due for co- Journal, Cecilie Rohwedder and David Subscription price is $15.00 per year for individu- ordinating the admission to NATO of Wessel criticized German universities in als, $21.00 for institutions and libraries ($21.00 Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hun- ways similar to those that Professor for individuals, $27.00 for libraries overseas, air gary. For the sixty million inhabitants of mail). The views expressed by authors of articles Skibniewski employs with regard to Pol- do not necessarily represent those of the Editors these countries, admission to NATO sym- ish universities (“Despite Proud Past, or of the Polish Institute. Articles are subject to bolically meant a readmission to the West- German Universities Fail by Many Mea- editing. Unsolicited manuscripts and other mate- ern world. As Professor Schlottmann sures”). -

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol. XXII, No. 3 September 2002 American Polish Writers Suzanne Strempek Shea. Photo by Nancy Palmieri. 890 THE SARMATIAN REVIEW September 2002 of Soviet deportations of Poles to the The Sarmatian Review (ISSN 1059-5872) is From the Editor Gulag. One learns from it that in western a triannual publication of the Polish Institute of Houston. This issue is dedicated to the English- Ukraine, many people who provided em- The journal deals with Polish, Central, and Eastern Euro- pean affairs, and their implications for the United States. language writers of Polish origin. Our ployment to others were deported, even We specialize in the translation of documents. lead review is of the most recent book those who hired housekeepers (thus al- Subscription price is $15.00 per year for individuals, $21.00 by Suzanne Strempek Shea in which leviating unemployment in the country- for institutions and libraries ($21.00 for individuals, $27.00 she plunges into the turbulent waters side). To procure the lists of people who for libraries overseas, air mail). The views expressed by authors of articles do not necessarily represent those of the of cancer survivors’ stories. Our re- had housekeepers must have involved Editors or of the Polish Institute. Articles are subject to edit- viewer, Professor Bogna Lorence-Kot, enormous work: one notes that the Sovi- ing. Unsolicited manuscripts and other materials are not wrote about Strempek Shea’s Lily of ets attached much weight to eliminating returned unless accompanied by a self-addressed and the Valley in the January 2000 issue those who were enterprising enough to stamped envelope. -

1 Journal Title Web Address Contact Details Additional Information From

Journal Title Web Address Contact Details Additional Information from the Journal/Publisher Website Central http://www.mane Lynne Medhurst at Maney Publishing: A refereed print journal published biannually devoted to Europe y.co.uk/search?f Tel: +44 (0)113 284 6135 history, literature, political culture, and society of the lands waction=show&f Fax: +44 (0)113 248 6983 once belonging to the Habsburg Empire and Poland-Lithuania wid=141 Email: [email protected] from the Middle Ages to the present. It publishes articles, debates, marginalia as well as book, music and film reviews Journal of http://www.tandf. No contact detalis available. Devoted to the process of regime change, including in its Communist co.uk/journals/titl material contributions from within the affected societies and to Studies and es/13523279.asp Chief & Managing Editor: Stephen White the effects of the upheaval on communist parties, ruling and Transition University of Glasgow, UK non-ruling, both in Europe and in the wider world Politics Magyar Lettre www.eurozine.co Eva Karadi, [email protected] Internationale, m Budapest NZ Mischa Gabowitsch (Moscow) Slavonic and http://www.mhra. Deputy Editor: Barbara Wyllie A quarterly published by the School of Slavonic and East East European org.uk/Publicatio Tel. +44 (0) 20 7679 8724 European Studies, University College London, devoted to Review ns/Journals/seer. Email: [email protected] Eastern Europe html Slovo http://www.ssees. Email: [email protected] A refereed journal discussing Russian, Eurasian, Central and ac.uk/slovo.htm -

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol. XX, No. 1 January 2000 Die Auswanderer The Central and Eastern Europeans’ Trek to America The monument honoring emigrants to America in Bremenhafen, Germany. Those who boarded ship in Bremen before the Great War included Poles from Prussian, Russian, and Austrian Poland. Seated at the monument are present-day Turkish immigrants to Germany. Photo by Ewa M. Thompson. 666 THE SARMATIAN REVIEW January 2000 The Sarmatian Review (ISSN 1059- problem in the interview published in this 5872) is a triannual publication of the Polish In- From the Editor issue. With less grace and less Christian stitute of Houston. The journal deals with Polish, This issue is devoted to the relationship charity, some colleagues told me that they Central, and Eastern European affairs, and their between America’s Central and Eastern have endured ignorance and boorishness implications for the United States. We specialize European ethnic communities and the of some Central European intellectuals in the translation of documents. intelligentsia in Central and Eastern Eu- Subscription price is $15.00 per year for individu- who visit these shores courtesy of Ameri- als, $21.00 for institutions and libraries ($21.00 rope. can sponsorship. Some Polish immi- for individuals, $27.00 for libraries overseas, air Some time ago, a colleague complained grants whose books are read only in Po- mail). The views expressed by authors of articles that his book on Polish American history land and who play negligible roles in do not necessarily represent those of the Editors which received favorable reviews in pro- or of the Polish Institute. -

2020 Do You Know Poland

DO YOU KNOW POLAND? BOOKS AND INFORMATION ON POLISH HISTORY AND CULTURE General History of Poland Patrice Dabrowski, Poland: The First Thousand Years (2014) Avoiding academic prose yet precise, this sweeping overview of the history of Poland into the 21st century is engagingly written but geared toward more scholarly audiences. Excellent source of knowledge about outstanding individuals, major turning points, and origins of such memorable mottos as " for our freedom and yours" which reverberated through the long history of struggles for Poland's independence and freedom during the 19th and 20th centuries. Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland (several editions between 1981 and 2005) The first of the “modern” studies of Poland, this detailed history in two volumes (Volume 1: The origins to 1795 and Volume 2: 1795 to the present) is also widely viewed as one of the best English-language works on the subject. Davies is widely known as a prolific writer and an expert on Polish and European history. Norman Davies, Europe: A History (1995) A highly innovative work that gives proper attention to Poland’s place in European history. From the review section of Good Reads website: "....histories should neither be told as stories or as simply a collection of facts, but something in between: Davies does it to near perfection. The writing is smooth and easily understandable for all." John Radzilowski, A Traveller’s History of Poland (2007, 2nd edition in 2014) Not a travelogue but an outstanding account of Poland's complex history and Poles' invincible spirit. Designed for general audiences, this clearly written and well- organized book includes numerous illustrations, maps, timelines, lists of historical figures, and a gazetteer. -

01Acta Slavicasort.P65

12 BETWEEN IMPERIAL TEMPTATION AND ANTI-IMPERIAL FUNCTION IN EASTERN EUROPEAN POLITICS: POLAND FROM THE EIGHTEENTH TO TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ANDRZEJ NOWAK WAS THE POLISH-LITHUANIAN COMMONWEALTH AN EMPIRE? There are two questions: how to analyse effectively the political structure and function of a vast Eastern European realm named through centuries the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and what it should properly be called? “Imperiological” studies, rapidly growing in the past two decades, form an original context in which a new answer to this perennial historical question seems possible: the Commonwealth was an empire. In fact, this name has already been given to the Polish-Lithuanian state, rather intuitively however, and in a not very convincing manner, in a few recent studies. “It is not customary to speak of a Polish empire, [...] but I do not see why the Swedes, with a Grand Duchy of Finland and other possessions in northern Germany, had an empire while the Poles did not” – based solely on this statement, a Harvard historian of Eastern European geopolitics, John P. LeDonne, posits a Polish empire on a par not only with the seventeenth century Swedish state, but with the Russian Empire of Peter the Great and his successors as well. Another American scholar, a political scientist, Ilya Prizel, stresses similarities between the Russian and Polish empires – as he calls them – due to their multinational structure and their supra-national elites.1 1 John P. LeDonne, The Russian Empire and the World 1700-1917. The Geopolitics of Expansion and Containment (New York, Oxford, 1997), p. 371; Ilya Prizel, National Identity and Foreign Policy. -

The Sarmatian Review

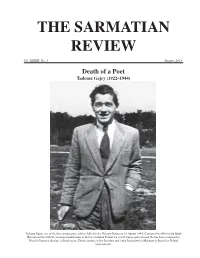

THE SARMATIAN REVIEW Vol. XXXIII, No. 1 January 2013 Death of a Poet Tadeusz Gajcy (1922–1944) Tadeusz Gajcy, one of the three young poet-soldiers killed in the Warsaw Rising on 16 August 1944. Consigned to oblivion by Jakub Berman and his fellow communist ideologues in Soviet-occupied Poland, he is now being rediscovered. He has been compared to Niccolo Paganini playing a Stradivarius. Photo courtesy of the Jarosław and Anna Iwaszkiewicz Museum in Stawisko, Poland (stawisko.pl). 1712 SARMATIAN REVIEW January 2013 The Sarmatian Review (ISSN 1059- Agata Brajerska-Mazur, A Strange Richard J. Hunter, Jr., is Professor 5872) is a triannual publication of the Polish Institute Poet: A Commentary on Cyprian of Legal Studies and Chair, of Houston. The journal deals with Polish, Central, Kamil Norwid’s Verse . .1723 Department of Economics and and Eastern European affairs, and it explores their implications for the United States. We specialize in Cyprian Kamil Norwid, Fatum and W Legal Studies, Stillman School of the translation of documents.Sarmatian Review is Weronie, translated by Patrick Business, Seton Hall University, indexed in the American Bibliography of Slavic and Corness . 1727 South Orange, New Jersey. East European Studies, EBSCO, and P.A.I.S. Leo V. Ryan, C.S.V. and Richard J. International Database. From January 1998 on, files John Lenczowski is Founder, Hunter, Jr., Poland, the European in PDF format are available at the Central and Eastern President, and Professor at The European Online Library (www.ceeol.com). Union, and the Euro . .1728 Subscription price is $21.00 per year for individuals, John Lenczowski, Poland on the Institute of World Politics, an $28.00 for institutions and libraries ($28.00 for Geopolitical Map . -

KATHERINE R. JOLLUCK Department of History 930 Lathrop Place MC 2024 Stanford, CA 94305 Stanford University 650-723-1884 Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected]

KATHERINE R. JOLLUCK Department of History 930 Lathrop Place MC 2024 Stanford, CA 94305 Stanford University 650-723-1884 Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Stanford University Stanford, CA 2001 - present. Senior Lecturer, Department of History; Affiliated faculty of the Program on Human Rights; Affiliated faculty of the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures; Affiliated faculty of the Europe Center; Resource faculty of the Program in Feminist Studies; Affiliated faculty of the Taube Center for Jewish Studies; Affiliated faculty of the Clayman Institute for Gender Research. 2007-08. Acting Director, Forum on Contemporary Europe, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. Aspasia 2009 – present. Editor of yearbook of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European Women's and Gender History. Published by Berghahn Books. Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA Spring 2002. Adjunct Professor, Department of National Security Affairs. Stanford University Overseas Studies Program Moscow, RUSSIA Fall 2000. Acting Assistant Professor. University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 1995 - 2000. Assistant Professor of Modern East European History. EDUCATION Stanford University Stanford, CA Ph.D. September 1995 in East European and Russian History. M.A. June 1990. Jagiellonian University Kraków, POLAND Summers 1987 and 1989. Advanced Polish language study. Pushkin Institute Moscow, USSR Spring 1986 and 1987-88. Graduate study and research in Russian language, literature, and pedagogy. Harvard University Cambridge, MA B.A. June 1985, cum laude. Major: Russian and Soviet Studies. AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS Faculty College Stanford, CA Team Leader, "Human Trafficking and Human Rights" 2012-2013. Leader of multidisciplinary group of scholars developing an undergraduate/graduate course on human trafficking.