Eden, the Fall, and Christ in Dante with Respect to Augustine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Storia Di Roma in Dante

FRANCESCA FONTANELLA La storia di Roma in Dante In L’Italianistica oggi: ricerca e didattica, Atti del XIX Congresso dell’ADI - Associazione degli Italianisti (Roma, 9-12 settembre 2015), a cura di B. Alfonzetti, T. Cancro, V. Di Iasio, E. Pietrobon, Roma, Adi editore, 2017 Isbn: 978-884675137-9 Come citare: Url = http://www.italianisti.it/Atti-di- Congresso?pg=cms&ext=p&cms_codsec=14&cms_codcms=896 [data consultazione: gg/mm/aaaa] L’Italianistica oggi © Adi editore 2017 FRANCESCA FONTANELLA La storia di Roma in Dante L’impero di Roma per Dante non è una realtà politica superata, ma una istituzione a lui contemporanea che si prolunga nel tempo da un lontano e nobile passato. La problematica ‘attuale’ del ruolo dell’impero nel mondo medievale influisce quindi profondamente sull’atteggiamento di Dante nei confronti della storia di Roma antica, che è chiamata in causa a dimostrare la ‘provvidenzialità’ e quindi la ‘giustizia’ dell’impero a lui contemporaneo. È una storia che ha come culmine Augusto, ovvero l’impero, della quale però si riportano essenzialmente fatti e personaggi in cui rifulge quella virtus repubblicana che avrebbe avuto il suo compimento proprio nel principato. Questa visione della storia di Roma è in fondo quella di Virgilio e di Livio: la prospettiva ‘attualizzante’ di Dante non costituisce quindi un impedimento alla comprensione dell’antica storia di Roma, ma anzi gli permette di entrare in sintonia con i suoi più antichi e autorevoli testimoni. La storia di Roma antica è per Dante, secondo la teoria della translatio imperii, la storia delle origini e dello sviluppo dell’impero a lui contemporaneo, ritenuto necessario al bene esse mundi.1 Pertanto questa storia è frequentemente chiamata in causa per dimostrare la ‘provvidenzialità’ e quindi la ‘giustizia’ di questo impero. -

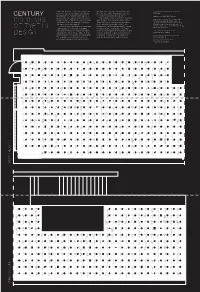

Century 100 Years of Type in Design

Bauhaus Linotype Charlotte News 702 Bookman Gilgamesh Revival 555 Latin Extra Bodoni Busorama Americana Heavy Zapfino Four Bold Italic Bold Book Italic Condensed Twelve Extra Bold Plain Plain News 701 News 706 Swiss 721 Newspaper Pi Bodoni Humana Revue Libra Century 751 Boberia Arriba Italic Bold Black No.2 Bold Italic Sans No. 2 Bold Semibold Geometric Charlotte Humanist Modern Century Golden Ribbon 131 Kallos Claude Sans Latin 725 Aurora 212 Sans Bold 531 Ultra No. 20 Expanded Cockerel Bold Italic Italic Black Italic Univers 45 Swiss 721 Tannarin Spirit Helvetica Futura Black Robotik Weidemann Tannarin Life Italic Bailey Sans Oblique Heavy Italic SC Bold Olbique Univers Black Swiss 721 Symbol Swiss 924 Charlotte DIN Next Pro Romana Tiffany Flemish Edwardian Balloon Extended Bold Monospaced Book Italic Condensed Script Script Light Plain Medium News 701 Swiss 721 Binary Symbol Charlotte Sans Green Plain Romic Isbell Figural Lapidary 333 Bank Gothic Bold Medium Proportional Book Plain Light Plain Book Bauhaus Freeform 721 Charlotte Sans Tropica Script Cheltenham Humana Sans Script 12 Pitch Century 731 Fenice Empire Baskerville Bold Bold Medium Plain Bold Bold Italic Bold No.2 Bauhaus Charlotte Sans Swiss 721 Typados Claude Sans Humanist 531 Seagull Courier 10 Lucia Humana Sans Bauer Bodoni Demi Bold Black Bold Italic Pitch Light Lydian Claude Sans Italian Universal Figural Bold Hadriano Shotgun Crillee Italic Pioneer Fry’s Bell Centennial Garamond Math 1 Baskerville Bauhaus Demian Zapf Modern 735 Humanist 970 Impuls Skylark Davida Mister -

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11

Design One Project Three Introduced October 21. Due November 11. Typeface Broadside/Poster Broadsides have been an aspect of typography and printing since the earliest types. Printers and Typographers would print a catalogue of their available fonts on one large sheet of paper. The introduction of a new typeface would also warrant the issue of a broadside. Printers and Typographers continue to publish broadsides, posters and periodicals to advertise available faces. The Adobe website that you use for research is a good example of this purpose. Advertising often interprets the type creatively and uses the typeface in various contexts to demonstrate its usefulness. Type designs reflect their time period and the interests and experiences of the type designer. Type may be planned to have a specific “look” and “feel” by the designer or subjective meaning may be attributed to the typeface because of the manner in which it reflects its time, the way it is used, or the evolving fashion of design. For this third project, you will create two posters about a specific typeface. One poster will deal with the typeface alone, cataloguing the face and providing information about the type designer. The second poster will present a visual analogy of the typeface, that combines both type and image, to broaden the viewer’s knowledge of the type. Process 1. Research the history and visual characteristics of a chosen typeface. Choose a typeface from the list provided. -Write a minimum150 word description of the typeface that focuses on two themes: A. The historical background of the typeface and a very brief biography of the typeface designer. -

Bishop Robert Barron Recommended Books

BISHOP ROBERT BARRON’S Recommended Books 5 FAVORITE BOOKS of ALL TIME SUMMA THEOLOGIAE Thomas Aquinas THE DIVINE COMEDY Dante Alighieri THE SEVEN STOREY MOUNTAIN Thomas Merton MOBY DICK Herman Melville MACBETH William Shakespeare FAVORITE Systematic Theology BOOKS CLASSICAL: • Summa Theologiae St. Thomas • On the Trinity (De trinitate) St. Augustine • On First Principles (De principiis) Origen • Against the Heresies (Adversus haereses) Irenaeus • On the Development of Christian Doctrine John Henry Newman MODERN/CONTEMPORARY: • The Spirit of Catholicism Karl Adam • Catholicism Henri de Lubac • Glory of the Lord, Theodrama, Theologic Hans Urs von Balthasar • Hearers of the Word Karl Rahner • Insight Bernard Lonergan • Introduction to Christianity Joseph Ratzinger • God Matters Herbert McCabe FAVORITE Moral Theology BOOKS CLASSICAL: • Secunda pars of the Summa theologiae Thomas Aquinas • City of God St. Augustine • Rule of St. Benedict • Philokalia Maximus the Confessor et alia MODERN/CONTEMPORARY: • The Sources of Christian Ethics Servais Pinckaers • Ethics Dietrich von Hilldebrand • The Four Cardinal Virtues and Faith, Hope, and Love Josef Pieper • The Cost of Discipleship Dietrich Bonhoeffer • Sanctify Them in the Truth: Holiness Exemplified Stanley Hauerwas FAVORITE Biblical Theology BOOKS CLASSICAL: • Sermons Origen • Sermons and Commentary on Genesis and Ennarationes on the Psalms Augustine • Commentary on John, Catena Aurea, Commentary on Job, Commentary on Romans Thomas Aquinas • Commentary on the Song of Songs Bernard of Clairvaux • Parochial and Plain Sermons John Henry Newman MODERN/CONTEMPORARY: • Jesus and the Victory of God and The Resurrection of the Son of God N.T. Wright • The Joy of Being Wrong James Alison • The Theology of the Old Testament Walter Brueggemann • The Theology of Paul the Apostle James D.G. -

3 a Martyr of Painting

The social lives of paintings in Sixteenth-Century Venice Kessel, E.J.M. van Citation Kessel, E. J. M. van. (2011, December 1). The social lives of paintings in Sixteenth-Century Venice. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18182 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral License: thesis in the Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18182 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 3 A Martyr of Painting Irene di Spilimbergo, Titian, and Venetian Portraiture between Life and Death Pygmalion’s love for the figure of ivory, which was made by his own hands, gives us an example of those people who try to circumvent the forces of nature, never willing to en- joy that sweet and soft love that regularly occurs between man and woman. While we are naturally always inclined to love, those people give themselves over to love things that are hardly fruitful, only for their own pleasure, such as Paintings, Sculptures, medals, or similar things. And they love them so dearly that those same things manage to satisfy their desires, as if their desire had been satisfied by real Love that has to be between man and woman.1 Giuseppe Orologi, comment on Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1578) As Giuseppe Orologi, a writer with connections to Titian, makes clear in his commentary on Ovid’s story of the sculptor Pygmalion, some people of his 1 ‘L’amore di Pigmaleone, alla figura di Avorio fatta da le sue mani, ci da essempio -

La Pia, Leggenda Romantica Di Bartolomeo Sestini

Edizioni dell’Assemblea 118 Ricerche La Pia, leggenda romantica di Bartolomeo Sestini a cura di Serena Pagani La Pia, leggenda romantica di Bartolomeo Sestini / a cura di Serena Pagani. - Firenze : Consiglio regionale della Toscana, 2015 1. Sestini, Bartolommeo < 1792-1822> 2. Pagani, Serena 3. Toscana <Regione>. Consiglio regionale 851.7 Sestini, Bartolommeo <1792-1822> - Poemi CIP (Cataloguing in publishing) a cura della Biblioteca del Consiglio regionale Volume in distribuzione gratuita Consiglio regionale della Toscana Settore Comunicazione, editoria, URP e sito web. Assistenza al Corecom Progetto grafico e impaginazione: Patrizio Suppa Pubblicazione realizzata dalla tipografia del Consiglio regionale, ai sensi della l.r. 4/2009 Dicembre 2015 ISBN 978-88-89365-59-5 Alle donne della mia famiglia e al mio Alessandro Sommario Premessa 9 Nota introduttiva 11 Nota al testo 29 Ringraziamenti 33 La Pia, leggenda romantica di Bartolomeo Sestini 35 Canto primo 39 Canto secondo 81 Canto terzo 121 Bibliografia di riferimento 151 Premessa Il desiderio di pubblicare una nuova edizione critica e commen- tata del componimento in ottave del pistoiese Bartolomeo Sestini sulla Pia senese è nato dall’intento di rendere omaggio all’autore che diede vita alla fortuna romantica del personaggio dantesco, la quale fiorì nei più svariati ambiti dell’arte, dalla letteratura alla pittura, dalla musica al teatro. Tramandiamo il testo nella sua forma originaria, come voluta dall’autore nella prima edizione romana del 1822, ma aggiungendo un commento critico, al fine di valorizzare appieno la personalità poetica di questo scrittore e patriota toscano, altra voce dell’Otto- cento, offuscata da quelle dei grandi contemporanei. Una nota introduttiva con la biografia di Bartolomeo Sestini e una breve sintesi sulla sua produzione letteraria precedono il testo; segue la storia delle edizioni maggiori della leggenda in ver- si romantica, tutte postume alla di lui morte. -

Quaderni D'italianistica : Revue Officielle De La Société Canadienne

Elio Costa From locus amoris to Infernal Pentecost: the Sin of Brunetto Latini The fame of Brunetto Latini was until recently tied to his role in Inferno 15 rather than to the intrinsic literary or philosophical merit of his own works.' Leaving aside, for the moment, the complex question of Latini's influence on the author of the Commedia, the encounter, and particularly the words "che 'n la mente m' è fìtta, e or m'accora, / la cara e buona imagine paterna / di voi quando nel mondo ad ora ad ora / m'insegnavate come l'uom s'ettema" (82-85) do seem to acknowledge a profound debt by the pilgrim towards the old notary. Only one other figure in the Inferno is addressed with a similar expression of gratitude, and that is, of course, Virgil: Tu se' lo mio maestro e'I mio autore; tu se' solo colui da cu' io tolsi lo bello stilo che m'ha fatto onore. {Inf. 1.85-87) If Virgil is antonomastically the teacher, what facet of Dante's cre- ative personality was affected by Latini? The encounter between the notary and the pilgrim in Inferno 15 is made all the more intriguing by the use of the same phrase "lo mio maestro" (97) to refer to Virgil, silent throughout the episode except for his single utterance "Bene ascolta chi la nota" (99). That it is the poet and not the pilgrim who thus refers to Virgil at this point, when the two magisterial figures, one leading forward to Beatrice and the other backward to the city of strife, conflict and exile, provides a clear hint of tension between "present" and "past" teachers. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Vettori, Italian

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Department of Italian 16:560:605 Dante Seminar Fall 2013 Alessandro Vettori Office Hours by appointment Department of Italian Tel 732-932-7536 84 College Avenue - Rm 101 Fax 732-932-1686 email: [email protected] The purpose of this course is the investigation of Dante’s opus in relation to other poets, philosophers, and theologians that had deep influences on his writing. Although only two of his major works will be read in their entirety, the Divine Comedy and the Vita nova, constant references will be made to other writings. Besides a stylistic and formal analysis, numerous thematic strains will be researched and followed throughout Dante’s production. Particular attention will be paid to such concepts as allegory, poetic auto-interpretation, autobiography, and the ever-changing concept of love. Learning goals: Students will be trained to do a close analysis of literary texts, to put poetic and prose texts in conversation with philosophical ideas, to discern the boundaries of literature, philosophy, and theology. They will be assessed by means of oral presentations (one long, one short), one short paper, one long (publishable) paper, and class participation. Syllabus Texts: Vita Nova (any annotated edition); Divina Commedia (any annotated edition); secondary materials will be made available on sakai. 09/09 Introduction. Exile, Poetry, Prayer. 09/16 Vita Nuova. Ronald Martinez, “Mourning Beatrice: The Rhetoric of Threnody in the Vita nuova,” Modern Language Notes 113 (1998): 1-29. 09/23 Vita Nuova. Teodolinda Barolini, “‘Cominciandomi dal principio infino a la fine’ (V.N. XXIII 15): Forging Anti-Narrative in the Vita Nuova,” La gloriosa donna de la mente. -

Total Depravity

TULIP: A FREE GRACE PERSPECTIVE PART 1: TOTAL DEPRAVITY ANTHONY B. BADGER Associate Professor of Bible and Theology Grace Evangelical School of Theology Lancaster, Pennsylvania I. INTRODUCTION The evolution of doctrine due to continued hybridization has pro- duced a myriad of theological persuasions. The only way to purify our- selves from the possible defects of such “theological genetics” is, first, to recognize that we have them and then, as much as possible, to set them aside and disassociate ourselves from the systems which have come to dominate our thinking. In other words, we should simply strive for truth and an objective understanding of biblical teaching. This series of articles is intended to do just that. We will carefully consider the truth claims of both Calvinists and Arminians and arrive at some conclusions that may not suit either.1 Our purpose here is not to defend a system, but to understand the truth. The conflicting “isms” in this study (Calvinism and Arminianism) are often considered “sacred cows” and, as a result, seem to be solidified and in need of defense. They have become impediments in the search for truth and “barriers to learn- ing.” Perhaps the emphatic dogmatism and defense of the paradoxical views of Calvinism and Arminianism have impeded the theological search for truth much more than we realize. Bauman reflects, I doubt that theology, as God sees it, entails unresolvable paradox. That is another way of saying that any theology that sees it [paradox] or includes it is mistaken. If God does not see theological endeavor as innately or irremediably paradoxical, 1 For this reason the author declines to be called a Calvinist, a moderate Calvinist, an Arminian, an Augustinian, a Thomist, a Pelagian, or a Semi- Pelagian. -

Haecceities, Quiddities, and Structure∗

compiled on 18 December 2015 at 14:00 Haecceities, quiddities, and structure∗ Wolfgang Schwarz Draft, 18 December 2015 Abstract. Suppose all truths are made true by the distribution of funda- mental properties and relations over fundamental particulars. The world is then completely characterized by stating which fundamental properties and relations are instantiated by which fundamental particulars. But do we have to mention the fundamental particulars by name? Arguably not. Arguably, all truths – or at least all truths we can ever know – are made true by the pattern in which fundamental properties and relations are instantiated by fundamental particulars, irrespective of the identity (“haecceity”) of those particulars. Parallel arguments suggest that the identity (“quiddity”) of fundamental properties and relations can be omitted. It would follow that all truths (or all knowable truths) are made true by the abstract structure of the world, the pattern in which fundamental properties and relations are instantiated by fundamental particulars, irrespective of the identity of the properties, relations, and particulars. I argue that this is almost correct: while not all truths are made true by the abstract structure of the world, the remaining truths are (in a certain sense) not made true by the world at all. 1 Introduction Most truths can be explained by other, more fundamental truths. That salt dissolves in water, for example, can be explained by the chemical composition of salt and water together with the general laws of physics. Explanations of this kind plausibly come to an end. At some point we reach a bottom level of fundamental facts that are not explainable in terms of anything more basic. -

Itinera Sarda.Pdf

university press ricerche storiche 8 Itinera Sarda Percorsi tra i libri del Quattro e Cinquecento in Sardegna a cura di Giancarlo Petrella CUEC Cooperativa Universitaria Editrice Cagliaritana RICERCHE STORICHE / 8 ISBN: 88-8467-175-2 Itinera Sarda. Percorsi tra i libri del Quattro e Cinquecento in Sardegna © 2004 CUEC Cooperativa Universitaria Editrice Cagliaritana prima edizione maggio 2004 La realizzazione di questo libro è stata resa possibile anche grazie al contributo del Soroptmist International d’Italia - Club di Oristano Senza il permesso scritto dell’Editore è vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, compresa la fotocopia, anche ad uso interno o didattico. Realizzazione editoriale: CUEC via Is Mirrionis 1, 09123 Cagliari Tel/fax 070271573 - 070291201 www.cuec.it e-mail: [email protected] In copertina: Pagina con decorazioni a penna da un incunabolo della Biblioteca Arcivescovile di Oristano Stampa: Solter – Cagliari Realizzazione grafica della copertina: Biplano – Cagliari Sommario 7 Premessa EDOARDO BARBIERI 9 Artificialiter scriptus: i più antichi libri a stampa conservati a Oristano EDOARDO BARBIERI 41 Di alcuni incunaboli conservati in biblioteche sassaresi EDOARDO BARBIERI 67 Gli incunaboli di Alghero (con qualche appunto sulla storia delle collezioni librarie in Sardegna) M. PAOLA SERRA 91 La Biblioteca Provinciale Francescana di San Pietro di Silki e le sue cinquecentine RAIMONDO TURTAS 145 Libri e biblioteche nei collegi gesuitici di Sassari e di Cagliari tra ’500 e prima metà del ’600 nella documentazione dell’ARSI GIANCARLO PETRELLA 175 ‘L’eretico travestito’: un capitolo poco conosciuto della fortuna della Sardiniae brevis historia et descriptio di Sigismondo Arquer PAOLA BERTOLUCCI 217 Per il censimento delle edizioni del XVI secolo in Sardegna 221 Indice dei nomi Premessa Dietro un titolo di tono vagamente settecentesco sono raccolti sette inter- venti dedicati ad indagare, sotto diversi aspetti, circolazione e conserva- zione del libro a stampa in Sardegna tra Umanesimo ed Età moderna.