Complaint Counsel's Response to Respondent's Motion to Compel Admissions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Alternative Dispute Resolution

“CONS” OF ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION I. FORUMS AND PROCEDURES FOR ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION A. FORUMS 1. Court – A case may be referred by the court to mediation or arbitration, which is usually before an attorney on the court’s mediation/arbitration panel. 2. Contract – The parties to a contract may include a provision that disputes are to be resolved by binding or non-binding mediation and/or arbitration. The parties may specify a forum such as the American Arbitration Association (“AAA”), JAMS/Endispute, or other associations. If no forum is specified by the parties, the rules of Code of Civil Procedure (“CCP”) §1280 et seq. apply. B. PROCEDURES – ADR Path [see Exhibit “A”] 1. Mediation Court – The rules for court-ordered mediation are set forth in CCP § 1775-1775.16, California Rules of Court (“CRC”) 1630- 1639, and in the local court rules. Contract – The rules for “private” mediation (i.e., a mediator required by contract or voluntarily agreed to by the parties) will depend upon the forum specified by the parties, i.e., the AAA, JAMS/Endispute, or other associations and unassociated mediators. 2. Arbitration Court – The procedures for Judicial Arbitration are found in CCP §1141.10 et seq., CRC Rules 1600 et seq., or local court rules. Contract -- If a contract contains a provision requiring disputes to be submitted to arbitration, then the rules governing Document #: 324 1 arbitration are found in CCP §1280 et seq. However, the parties may provide in a contract that disputes are to be submitted to arbitration and then specify the rules applicable to the arbitration. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Kansas

Case 2:09-cv-02304-JAR Document 77 Filed 09/08/10 Page 1 of 37 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS REGINA DANIELS, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 09-2304-JAR ) UNITED PARCEL SERVICE, INC., ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter comes before the Court upon Plaintiff’s Motion to Compel Discovery and for Related Sanctions (Doc. 64). The motion is fully briefed, and the Court is prepared to rule. For the reasons stated below, Plaintiff’s motion is granted in part and denied in part. I. Procedural Requirement to Confer Before considering the merits of Plaintiff’s motion to compel, this Court must first determine whether Plaintiff has complied with the requirements of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and this district’s local rules regarding the movant’s duty to confer with opposing counsel prior to filing a motion to compel. Fed. R. Civ. P. 37(a)(1) provides that a motion to compel “must include a certification that the movant has in good faith conferred or attempted to confer with the person or party failing to make disclosure or discovery in an effort to obtain it without court action.” D. Kan. R. 37.2 expands on the movant’s duty to confer, stating “[a] ‘reasonable effort to confer’ means more than mailing or faxing a letter to the opposing party. It requires that the parties in good faith converse, confer, compare views, consult and deliberate, or in good faith attempt to do so.” In this case, the parties have exchanged correspondence aimed at attempting to resolve the instant discovery dispute without judicial intervention. -

Request for Admissions

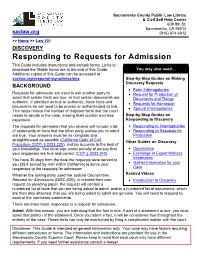

Sacramento County Public Law Library & Civil Self Help Center 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DISCOVERY Requests for Admission This Guide includes instructions and sample forms. Links to download the fillable forms are at the end of this Guide. Additional copies of this Guide can be accessed at saclaw.org/request-admissions BACKGROUND Requests for admission are used to ask another party to You may also need… admit that certain facts are true, or that certain documents are authentic. If admitted as true or authentic, these facts and Step-by-Step Guides on documents do not need to be proven or authenticated at trial. Responding to Discovery This helps narrow the scope of controversy in the case, making trials quicker and less expensive. • Responding to Interrogatories • Ideally, the facts you need to win your case are undisputed, Responding to Requests for and the other side will admit that these facts are true. If all the Admission • key facts are admitted or deemed true, you may be able to file Responding to Requests for a motion asking the judge to issue a judgment in your favor, Production because there are no factual issues to be tried. Step-by-Step Guides on Making Jury instructions are a good way to know what facts you will Discovery Requests need to prove in order for you to win your case. The California • Civil Jury Instructions (CACI) are available for free online at Form Interrogatories • www.courts.ca.gov/partners/juryinstructions.htm. If you find Request for Production of the jury instructions appropriate to your case, you will have a Documents and Things list of the facts each side must establish to win the case. -

Responding to Requests for Admission This Guide Includes Instructions and Sample Forms

Sacramento County Public Law Library & Civil Self Help Center 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DISCOVERY Responding to Requests for Admission This Guide includes instructions and sample forms. Links to download the fillable forms are at the end of this Guide. You may also need… Additional copies of this Guide can be accessed at saclaw.org/respond-req-admissions. Step-by-Step Guides on Making Discovery Requests BACKGROUND Form Interrogatories Requests for admission are used to ask another party to Request for Production of admit that certain facts are true, or that certain documents are Documents and Things authentic. If admitted as true or authentic, these facts and Requests for Admission documents do not need to be proven or authenticated at trial. Special Interrogatories This helps reduce the number of disputed facts that the court needs to decide in the case, making trials quicker and less Step-by-Step Guides on expensive. Responding to Discovery The requests for admission that you receive will include a list Responding to Interrogatories of statements or facts that the other party wishes you to admit Responding to Requests for are true. Your answers must be as complete and Production straightforward as possible (California Code of Civil Other Guides on Discovery Procedure (CCP) § 2033.220), and be accurate to the best of your knowledge. You must sign under penalty of perjury that Depositions your responses are true and correct (CCP § 2033.240). Exchange of Expert Witness Information You have 30 days from the date the requests were served to you (35 if served by mail within California) to serve your Gather Information for your responses to the requests for admission. -

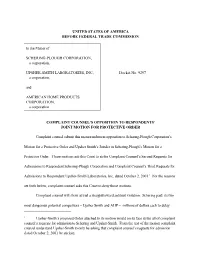

Upsher-Smith's Proposed Order Attached to Its Motion Would on Its

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION In the Matter of SCHERING-PLOUGH CORPORATION, a corporation, UPSHER-SMITH LABORATORIES, INC., Docket No. 9297 a corporation, and AMERICAN HOME PRODUCTS CORPORATION, a corporation COMPLAINT COUNSEL’S OPPOSITION TO RESPONDENTS’ JOINT MOTION FOR PROTECTIVE ORDER Complaint counsel submit this memorandum in opposition to Schering-Plough Corporation’s Motion for a Protective Order and Upsher Smith’s Joinder in Schering-Plough’s Motion for a Protective Order. Those motions ask this Court to strike Complaint Counsel’s Second Requests for Admissions to Respondent Schering-Plough Corporation and Complaint Counsel’s Third Requests for Admissions to Respondent Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Inc. dated October 2, 2001.1 For the reasons set forth below, complaint counsel asks this Court to deny those motions. Complaint counsel will show at trial a straightforward antitrust violation: Schering paid its two most dangerous potential competitors – Upsher Smith and AHP – millions of dollars each to delay 1 Upsher-Smith’s proposed Order attached to its motion would on its face strike all of complaint counsel’s requests for admission to Schering and Upsher-Smith. From the text of the motion complaint counsel understand Upsher-Smith to only be asking that complaint counsel’s requests for admission dated October 2, 2001 be sticken. their competitive entry. Respondents chosen defense to this straightforward antitrust case is to divert attention from its anticompetitive conduct to collateral issues, such as -

United States' First Request for Admissions, Second Set of Interrogatories and Second Request for Production of Documents to Clarke Container, Inc

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO WESTERN DIVISION EPA Region 5 Records Ctr. THE DOW CHEMICAL CO., et aE, Plaintiffs, 274494 v. Civil Action Nos. C-l-97-0307;C-l-97-0308 ACME WRECKING CO., INC., et §1, (Consolidated Actions) Defendants. C-l-01-439 (Transferred Action) THE I )OW CHEMICAL CO., et aE Judge Weber Plaintiffs, v. SUN ' HE COMPANY, d/b/a SUNOCO OlLCORP..etaL. Defendants. UNITED STATUS OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, v. AERONCA, INC..eta]. Defendants. UNITED STATES' FIRST REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS, SECOND SET OF INTERROGATORIES AND SECOND REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS TO CLARKE CONTAINER, INC. Pursuant to Rules 26, 33, 34, and 36 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Plaintiff, the United States of America, requests that Defendant Clarke Container, Inc. ("Clarke Container"): (1) admit or answer the following requests for admission within forty-five days, as provided for in the First Case Management Order ("First CMO") entered in the above-captioned action; (2) answer fully, in writing and under oath, each of the following interrogatories, and serve such answers on the undersigned counsel for the United States within forty-five days, as provided for in the First CMO; and (3) produce the documents requested below, or in lieu thereof serve authentic copies of such documents on the undersigned counsel for the United States within forty-five days, as provided for in the First CMO. CRITICAL INSTRUCTION TO CLARKE CONTAINER This discovery request is directed to Clarke Container. According to documents both in the public record and in the custody of U.S. -

Discovery Traps… & How to Get out of Them

DISCOVERY TRAPS… & HOW TO GET OUT OF THEM KRISTAL C. THOMSON WILSON, PENNYPACKER & THOMSON, L.L.P. 8620 N. New Braunfels, Suite 101 San Antonio, Texas 78217 State Bar of Texas 37TH ANNUAL ADVANCED FAMILY LAW COURSE August 1-4, 2011 San Antonio CHAPTER 19 Kristal Cordova Thomson WILSON, PENNYPACKER & THOMSON, L.L.P. 8620 N. New Braunfels, Suite 101 San Antonio, Texas 78217 210.826.4001 [email protected] LICENSES/CERTIFICATIONS: State Bar of Texas; 2002 United States District Courts, Western District; 2003 Board Certified – Family Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization; 2009 EDUCATION: Juris Doctorate, St. Mary’s University School of Law; 2002 Bachelor of Arts, University of Texas; 1995 CURRENT PROFESSIONAL Director, St. Mary’s Law Alumni Association ACTIVITIES: *Elected, 2005 – 2010 * Former Treasurer & Secretary Council Member Class of 2014, Family Law Council, State Bar of Texas * Elected, 2009 *Web Site Chair *Amicus Committee Treasurer, San Antonio Family Lawyers Association * Elected 2010-2011 COMMUNITY/NON-PROFIT Board of Directors, Special Olympics Texas; 2009-2011 ACTIVITIES: Appointed Committee Member, Alamo Bowl; 2005-2011 Volunteer, Junior League San Antonio; 2004-2011 Volunteer, Community Justice Program; 2003-2011 PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS: Member, Texas Academy of Family Law Specialists; since 2010 Member, San Antonio Bar Association; since 2002 * Former Board Member, 2008-2010 Member, San Antonio Young Lawyers Association; since 2002 * Former President, 2005-2006 Member, Bexar County Women’s Bar Association; since -

In the District Court of Appeal of the State of Florida Fifth District

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA FIFTH DISTRICT NOT FINAL UNTIL TIME EXPIRES TO FILE MOTION FOR REHEARING AND DISPOSITION THEREOF IF FILED WELLS FARGO BANK, N.A., Appellant, v. Case No. 5D15-3283 CINDY SHELTON and HOWARD SHELTON, Appellees. ________________________________/ Opinion filed July 7, 2017 Appeal from the Circuit Court for Brevard County, Charles G. Crawford, Judge. Sara F. Holladay-Tobias, Emily Y. Rottmann, and C. H. Houston, lll, of McGuireWoods LLP, Jacksonville, for Appellant. Richard S. Shuster and Purvi S. Patel, of Shuster & Saben, LLC, Satellite Beach, for Appellees. COHEN, C.J. This appeal stems from the trial court’s reluctance to grant relief from technical admissions due to counsel’s lack of diligence in pursuing relief. The attorney for Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. (“Wells Fargo”) failed to timely respond to the Sheltons’ request for admissions.1 The allegations were then deemed admitted, resulting in the entry of 1 Wells Fargo’s current appellate counsel is not the same attorney who represented it at trial. summary judgment in favor of the Sheltons based on the technical admissions. However, because the pleadings and other record evidence contradicted those admissions and the Sheltons did not demonstrate prejudice, we reverse and remand for further proceedings. Wells Fargo filed a foreclosure complaint against the Sheltons in 2013. A copy of the note executed by the Sheltons was attached to the complaint, which indicated that Wells Fargo was the original lender on the note. A copy of the mortgage was also attached to the complaint. The parties engaged in discovery, during which the Sheltons sent Wells Fargo a request for admissions. -

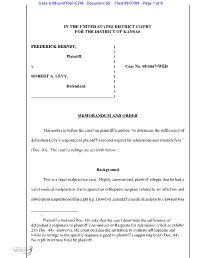

Case 6:08-Cv-01067-EFM Document 65 Filed 08/07/09 Page 1 of 9

Case 6:08-cv-01067-EFM Document 65 Filed 08/07/09 Page 1 of 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS FREDERICK BERNDT, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 08-1067-WEB ) ROBERT A. LEVY, ) ) Defendant. ) ) ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER This matter is before the court on plaintiff’s motion “to determine the sufficiency of defendant Levy’s responses to plaintiff’s second request for admissions and attorney fees.” (Doc. 43). The court’s rulings are set forth below.1 Background This is a legal malpractice case. Highly summarized, plaintiff alleges that he had a valid medical malpractice claim against an orthopedic surgeon related to an infection and subsequent amputation of his right leg. However, plaintiff’s medical malpractice lawsuit was 1 Plaintiff’s motion (Doc. 43) asks that the court determine the sufficiency of defendant’s responses to plaintiff’s second set of Requests for Admission (cited as exhibit 2 to Doc. 44). However, the court declines the invitation to evaluate all requests and limits its rulings to the specific requests argued in plaintiff’s supporting brief (Doc. 44). No reply brief was filed by plaintiff. Case 6:08-cv-01067-EFM Document 65 Filed 08/07/09 Page 2 of 9 dismissed based on a statute of limitations defense. Plaintiff now alleges that defendant Robert Levy, the attorney handling the medical malpractice claim, was negligent in allowing the statute of limitations to expire before filing suit against the surgeon. Plaintiff’s Motion As noted above, plaintiff moves the court to determine the sufficiency of defendant’s answers and objections to certain requests for admission pursuant to Fed. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Iowa Western Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF IOWA WESTERN DIVISION JOETTA HEARING, Plaintiff, No. C13-4101-LTS vs. ORDER MINNESOTA LIFE INS. CO., Defendant, vs. NIKOLE C. HOLLOWAY, Third-Party Defendant. ____________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 2 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................. 2 III. ANALYSIS ................................................................................... 4 A. The Motion to Deposit Funds .................................................... 4 1. Is Interpleader Appropriate? ............................................. 4 2. Attorney Fees and Costs ................................................. 10 a. Legal Standard ................................................... 10 b. Discussion ......................................................... 12 B. The Motion to Dismiss/Motion for Summary Judgment .................. 14 1. Arguments of the Parties ............................................... 14 2. Applicable Standards .................................................... 16 3. Undisputed Facts ......................................................... 17 4. Discussion ................................................................. 18 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................ 25 Case 5:13-cv-04101-LTS Document 38 Filed 07/21/14 Page 1 of 26 I. INTRODUCTION This case is before me on: (a) a motion (Doc. -

United States District Court of Connecticut Local Rules

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT LOCAL RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE LOCAL RULES FOR MAGISTRATE JUDGES LOCAL RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE Amended December 1, 2009* *If a Rule was amended after December 2009, the date of amendment is located on the page of the Rule. TABLE OF CONTENTS JUDGES OF THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT ............................................................................................................................ 1 LOCAL RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE ..................................................................................... 2 RULE 1 ...................................................................................................................................... 2 SCOPE OF RULES ................................................................................................................... 2 (a) Title and Citation ......................................................................................................... 2 (b) Effective Date .............................................................................................................. 2 (c) Definitions ................................................................................................................... 2 RULE 2 ...................................................................................................................................... 3 (RESERVED) ........................................................................................................................... -

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Interpreted Carl C

Cornell Law Review Volume 25 Article 3 Issue 1 December 1939 Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Interpreted Carl C. Wheaton Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl C. Wheaton, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Interpreted , 25 Cornell L. Rev. 28 (1939) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol25/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEDERAL RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE INTERPRETED CARL C. WHEATON As this is written, the new Federal Rules of Civil Procedure have been in effect for nearly a year. It should be of some interest and value, therefore, to have available an interpretation of these rules as it is discovered in the cases and legal journals. An earnest effort has been made to present a complete, accurate review of this material, including, reasoning when that is found. Occasionally, the writer has expressed his own opinion in instances of conflict of ideas or when a single line of authority seems incorrect. RULES GENERALLY As might be expected, there has been a large number of articles on the rules generally.' Sometimes they have attempted a comparison of local procedure with the new rules. They do not cite many authorities, yet they have been of some value in giving lawyers a general idea of what they should do proced- urally.