Pregnant Text and the Conception of the Khalsa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhai Mani Singh Contribtion in Sikh History

© 2018 JETIR August 2018, Volume 5, Issue 8 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) BHAI MANI SINGH CONTRIBTION IN SIKH HISTORY Simranjeet Kaur, M.Phil. Research Scholar, History Department, Guru Kashi University, Talwandi Sabo. Dr. Daljeet Kaur Gill, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Guru Kashi University, Talwandi Sabo. ABSTRACT Bhai Mani Singh is an important personality in Sikh History. He was a very good speaker and writer. He performed the service of a priest in Amritsar and played an important role in reforming the dismal conditions there. He spent all his life for saving the unity, integrity and honour of Sikh religion and promoted knowledge among the Sikhs by becoming the founder of the Giani Sect. He created an example for the coming generations by sacrificing himself at the age of ninety years. The sacrifice of Bhai Mani Singh filled every Sikh with a wave of anger and impassion. His unique martyrdom had turned the history of Sikhism forwards. His personality, in real meaning; is a source of inspiration for his followers. Sikh history, from the very beginning, has an important place in human welfare and social reforms for its sacrifices and martyrdoms. The ancestors and leaders of Sikh sect made important contributions at different times and places. Bhai Mani Singh showed his ability in different tasks initiated by Sikh Gurus by remaining in Sikh sect ant took the cause of social reforms to a new height. To keep the dignity of Sikh History intact, he sacrificed his life by getting himself chopped into pieces at the age of 90 for not being able to pay the prescribed taxes.1 While making an unparallel contribution in the Sikh history, Bhai Mani Singh performed the service of a priest in Amritsar and played an important role in reforming the dismal conditions there. -

Study Guid E

Year: 5 Subject: RE Unit of Study: Sikhism Linked Literature: We are Sikhs/My Sikh Faith or Ada Twist, Scientist by Andrea Beaty Special people in the Sikh Who are Sikhs? Special books in Sikhism Sikh places of worship Sikh family life Sikh celebrations faith Vocabulary I need to know: I need to do: Prior knowledge: Sikhism is a monotheistic religion because they believe in only one God Describe the key teachings and beliefs of Different religions have different be- Sikh Means disciple in Punjabi (Waheguru) who created the world and that different religions are all paths to this a religion, explaining how they shape the liefs and practises lives of individuals and contribute to Disciple Follower of God same God. It is one of the world’s youngest religions, founded about 500 years ago, in 1499, by Guru Nanak in the Punjab, Northern India. It is the fifth largest religion society. Some religious beliefs and practises Waheguru Wonderful lord or God in the world with over 20 million followers. People who follow Sikhism are called Explain practises and lifestyles associated with belonging to a faith. are similar across religions Cycle of many lives - rebirth of a soul in Sikhs. The word Sikh means ‘disciple’ in Punjabi. Sikhs are the disciples of God Reincarnation another body who follow the writings and teachings of the Ten Sikh Gurus. Devotion to God Explain some of the different ways indi- should be shown daily by meditating, praying and following the core beliefs, as well viduals show their beliefs. Religions have different place of wor- Released from the cycle of rebirth impelled by Explain own ideas about ‘tricky’ ques- ship, special (holy) books and tradi- Mukti/moksha the law of karma as behaving in a manner that creates good karma. -

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib As the Only Sikh Canon

Presently Published Dasam Granth and British Connection; Guru Granth Sahib as the only sikh canon (From www.GlobalSikhStudies.net) Jasbir Singh Mann M.D., California. The lineage of Personal Guruship was terminated ( Canon Closed) on October, 6th Wednesday1708 A.D. by the 10th Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, after finalizing the sanctification of Guru Nanak’s Mission and passing the succession to Guru Granth Sahib as future Guru of the Sikhs. This was the final culmination of the Sikh concept of Guruship, capable of resisting the temptation of continuation of the lineage of human Gurus. The Tenth Guru while maintaining the concept of ‘Shabad Guru’ also made the Panth distinctive by introducing corporate Guruship. The concept of Guruship continued and the role of human gurus was transferred to the Guru Panth and that of the revealed word to Guru Granth Sahib making Sikhism a unique modern religion. This historical fact is well documented in Indian, Persian and Western Sikh sources of 18th century. Indian sources: Sainapat (1711), Bhai Nand Lal, Bhai Prahlad, and Chaupa Singh, Koer Singh (1751), Kesar Singh Chhibber (1769-1779Ad), Mehama Prakash (1776), Munshi Sant Singh ( on account of Bedi family of the Ulna, Unpublished records), Bhatt Vahi’s. Persian sources: Mirza Muhammad (1705-1719 AD), Sayad Muhammad Qasim (1722 AD), Hussain Lahauri(1731), Royal Court News of Mughals, Akhbarat-i-Darbar-i-Mualla (1708). Western sources: Father Wendel, Charles Wilkins, Crauford, James Browne, George Forester, and John Griffith. These sources clearly emphasize the tenets of Nanak as enshrined in Guru Granth Sahib as the only promulgated scripture of the Sikhs. -

Harish Ji Mata Sahib Kaur Girls Hostel

MATASAHIBKAUR TheMotherOfTheKhaisa Mata Sahib Kaur Girls' Hostel 2019-20 A large number of girl students from outside Delhi even from smaller towns aspire to have access to education in the capital and Delhi University is replete with examples of young and enterprising women who have made a mark in the society. Seeing this, Sri Guru Gobind Singh College of Commerce has decided to develop hostel facilities for the girl students in the name of Mata Sahib Kaur Ji. The hostel is located inside the college campus. With 42 rooms, it can accommodate the 126 undergraduate girl students of the college. Mata Sahib Kaur is wife of Guru Gobind Singh Ji. She is proclaimed to be the Mother of the Khalsa. The Khalsa was declared to be the sons and daughters of Guru Gobind Singh and Mata Sahib Kaur. She was epitome of qualities of humility and sacrifice having a complete faith in Almighty. She mixed sugary balls into Amrit that was been administered to the Sangat signifying that strength must be mingled with accompanying sweetness. After the battle of Anandpur Sahib when the entire family of Guru Gobind Singh was separated, Mata Sahib Kaur accompanied Guru Gobind Singh to Delhi and thereafter to Nanded. When Guru Gobind Singh realized that the time has come when He was to leave for the heavenly abode, Mata Sahib Kaur was told by him to leave the place and join Mata Sundari in Delhi. Guru Gobind Singh handed to Mata Sahib Kaur five weapons and his Insignia through which 9 Hukamnamas (Letter of Command) was issued for the Khalsa. -

Guru Tegh Bahadur

Second Edition: Revised and updated with Gurbani of Guru Tegh Bahadur. GURU TEGH BAHADUR (1621-1675) The True Story Gurmukh Singh OBE (UK) Published by: Author’s note: This Digital Edition is available to Gurdwaras and Sikh organisations for publication with own cover design and introductory messages. Contact author for permission: Gurmukh Singh OBE E-mail: [email protected] Second edition © 2021 Gurmukh Singh © 2021 Gurmukh Singh All rights reserved by the author. Except for quotations with acknowledgement, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or medium without the specific written permission of the author or his legal representatives. The account which follows is that of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Nanak IX. His martyrdom was a momentous and unique event. Never in the annals of human history had the leader of one religion given his life for the religious freedom of others. Tegh Bahadur’s deed [martyrdom] was unique (Guru Gobind Singh, Bachittar Natak.) A martyrdom to stabilize the world (Bhai Gurdas Singh (II) Vaar 41 Pauri 23) ***** First edition: April 2017 Second edition: May 2021 Revised and updated with interpretation of the main themes of Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Gurbani. References to other religions in this book: Sikhi (Sikhism) respects all religious paths to the One Creator Being of all. Guru Nanak used the same lens of Truthful Conduct and egalitarian human values to judge all religions as practised while showing the right way to all in a spirit of Sarbatt da Bhala (wellbeing of all). His teachings were accepted by most good followers of the main religions of his time who understood the essence of religion, while others opposed. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

Of Our 10Th Master - Dhan Guru Gobind Singh Ji Maharaj

TODAY, 25th December 2017 marks the Parkash (coming into the world) of our 10th master - Dhan Guru Gobind Singh Ji Maharaj. By dedicating just 5 minutes per day over 4 days you will be able to experience this saakhi (historical account) as narrated by Bhai Vishal Singh Ji from Kavi Santokh Singh Ji’s Gurpartap Suraj Granth. Please take the time to read it and immerse yourselves in our rich and beautiful history, Please share as widely as possible so we can all remember our king of kings Dhan Guru Gobind Singh Ji on this day. Let's not let today pass for Sikhs as just being Christmas! Please forgive us for any mistakes. *Some background information…* When we talk about the coming into this world of a Guru Sahib, we avoid using the word ‘birth’ for anything that is born must also die one day. However, *Satgur mera sada sada* The true Guru is forever and ever (Dhan Guru Ramdaas Ji Maharaj, Ang 758) Thus, when we talk about the coming into the world of Guru Sahibs we use words such as Parkash or Avtar. This is because Maharaj are forever present and on this day They simply became known/visible to us. Similarly, on the day that Guru Sahib leave their physical form, we do not use the word death because although Maharaj gave up their human form, they have not left us. Their jot (light) was passed onto the next Guru Sahib and now resides within Dhan Guru Granth Sahib Ji Maharaj. So, you will often hear people say “Maharaj Joti Jot smaa gai” meaning that their light merged back into the light of Vaheguru. -

The Doctrinal Inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : in Relation to Avtarhood(Part I)

The Doctrinal inconsistencies in Dasam Granth : In relation to Avtarhood(Part I) Prof.Gurnam Kaur* (A) Introduction:- This paper is concerned with the authenticity of the compositions included in the Dasam Granth or we can say with the doctrinal inconsistencies in the Dasam Granth in relation to the idea of avtarhood,i.e. incarnation of God in different forms human or any, devi pooja (worship of goddess) shastar as Pir i.e. to worship weapons as the highest spiritual person, bias against unshorn hair, supporting the use of intoxicants and bias against woman. To judge all these things we have to take the help of Sikh tenants and adopt some basic criterion or methodology because these days animated discussions are going on about the Dasam Granth. The text has already been analyzed by known scholars from the historical, religious and theological points of view. Being the student of Sikh philosophy, with due regards to the analysis already done, I will try to analyze the text in the light of Sri Guru Granth Sahib. Sri Guru Granth Sahib is the basic and primary scripture of Sikh religion. No other scripture can be considered equal to it. This is the only Scripture in the history of the world religions which was compiled by its founder Gurus themselves. The fifth Guru Arjan Dev compiled the first recension and installed it at Harmander Sahib on Bhadon sudi. I, 1604 A.D. Bhai Gurdas was the first scribe and Baba Budha Ji was made the first Granthi. Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth and last physical Guru, added the bani composed by Guru Teg Bahadur, the ninth Nanak Joti and bestowed 1 Guruship on the Granth before his final departure in samat 1765 from this mundane world. -

Guru Gobind Singh

GURU GOBIND SINGH MADHU KALIMIPALLI Coin depicting Guru Gobind Singh from 1747 CE BIRTH OF GURU GOBIND SINGH • Guru Gobind Singh Ji (1661 - 1708), born "Gobind Rai" at Patna Sahib, Bihar, India, was the tenth and last of the ’Human form of Gurus’ of Sikhism. • He was born to Mata Gujri and Guru Tegh Bahadur Jin in 1661. • He became Guru on November 24, 1675 at the age of nine, following the martyrdom of his father, the ninth Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur Ji. GURU GOBIND SINGH LAST OF 10 SIKH GURUS The ten Sikh gurus in order are: • Guru Tegh Bahadur (1665 - 1675). • Guru Nanak (1469 - 1539). ... • Guru Gobind Singh (1675 - 1708). • Guru Angad (1539 - 1552). ... • Guru Amar Das (1552 - 1574). ... • Guru Ram Das (1574 - 1581). ... • Guru Gobind Singh was the last of the • Guru Arjan (1581 - 1606). ... human gurus. He introduced the Khalsa, • Guru Hargobind (1606 - 1644). ... or ‘pure ones’ and the ‘five Ks'. Just before he died in 1708, he proclaimed • Guru Har Rai (1644 - 1661). ... Guru Granth Sahib - the Sikh scripture - • Guru Har Krishan (1661 - 1664). as the future guru. Guru Gobind Singh with his horse LIFE OF GURU GOBIND SINGH • Guru Gobind Singh was a divine messenger, a warrior, a poet, and a philosopher. • He was born to advance righteousness and Dharma , emancipate the good, and destroy all evil-doers. • He molded the Sikh religion into its present shape, with the institution of the Khalsa fraternity, and the completion of the sacred scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib Ji, in the Before leaving his mortal body in 1708, Guru Gobind Singh final form that we see today. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Assistance Series HAROLD M. JONES Interviewed by: Self Initial interview date: n/a Copyright 2002 ADST Dedicated with love and affection to my family, especially to Loretta, my lovable supporting and charming wife ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The inaccuracies in this book might have been enormous without the response of a great number of people I contacted by phone to help with the recall of events, places, and people written about. To all of them I am indebted. Since we did not keep a diary of anything that resembled organized notes of the many happenings, many of our friends responded with vivid memories. I have written about people who have come into our lives and stayed for years or simply for a single visit. More specifically, Carol, our third oldest daughter and now a resident of Boulder, Colorado contributed greatly to the effort with her newly acquired editing skills. The other girls showed varying degrees of interest, and generally endorsed the effort as a good idea but could hardly find time to respond to my request for a statement about their feelings or impressions when they returned to the USA to attend college, seek employment and to live. There is no one I am so indebted to as Karen St. Rossi, a friend of the daughters and whose family we met in Kenya. Thanks to Estrellita, one of our twins, for suggesting that I link up with Karen. “Do you use your computer spelling capacity? And do you know the rule of i before e except after c?” Karen asked after completing the first lot given her for editing. -

Religious Studies - Is Langar About More Than Food? Year 9 Term 6

Religious Studies - Is Langar About More Than Food? Year 9 Term 6 Stories of the Gurus Key Terms Sewa The Guru visited a village and stayed with a poor Sewa through the Langar man. A rich man tried to tempt the Guru into staying Gurdwara The Sikh place of worship. ‘Gateway to the Guru’ at his house by preparing a feast. The poor man There are a range of ways you can participate in sewa through the only had enough flour for one chapati for the Guru langar. Guru Nanak and so was very upset. However, the Guru refused These include: and the to stay with the rich man because, although he had Guru Granth Sahib The Sikh holy book. 1. Cooking and preparing food whilst saying prayers. This is always Chapattis more, he had not earnt this in an honest way. He vegetarian. had hurt others in the process whereas the poor 2. Cleaning before and after langar service, for example, washing up. man earnt a fair and honest living. The rich man 3. Serving the food to the people who have come to the langar for a meal. was very ashamed of himself. Langar A free meal/ a communal kitchen. International langar week The Gurus father gave him some money to go and trade, to make himself rich in the city and buy The room where the Guru Granth Sahib is kept International Langar week: Each year in October, Sikhs mark Sach Khand beautiful things. On his journey, Guru saw around overnight in the gurdwara. ‘International Langar Week’ during which Sikhs are asked to do 3 things: twenty good men in prayer, but they looked very Introduce a friend to the langar Guru Nanak 1. -

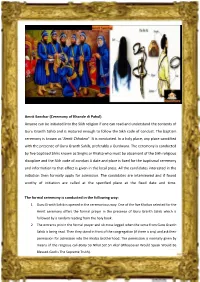

Amrit Sanskar) Should Be Held at an Exclusive Place Away from Common Human Traffic

Amrit Sanchar (Ceremony of Khande di Pahul) Anyone can be initiated into the Sikh religion if one can read and understand the contents of Guru Granth Sahib and is matured enough to follow the Sikh code of conduct. The baptism ceremony is known as 'Amrit Chhakna". It is conducted. In a holy place, any place sanctified with the presence of Guru Granth Sahib, preferably a Gurdwara. The ceremony is conducted by five baptized Sikhs known as Singhs or Khalsa who must be observant of the Sikh religious discipline and the Sikh code of conduct A date and place is fixed for the baptismal ceremony and information to that effect is given in the local press. All the candidates interested in the initiation then formally apply for admission. The candidates are interviewed and if found worthy of initiation are called at the specified place at the fixed date and time. The formal ceremony is conducted in the following way: 1 Guru Granth Sahib is opened in the ceremonious way. One of the five Khalsas selected for the Amrit ceremony offers the formal prayer in the presence of Guru Granth Sahib which is followed by a random reading from the holy book. 2 The entrants join in the formal prayer and sit cross legged when the verse from Guru Granth Sahib is being read. Then they stand in front of the congregation (if there is any) and ask their permission for admission into the Khalsa brotherhood. The permission is normally given by means of the religious call-Bolay So Nihal Sat Sri Akal (Whosoever Would Speak Would Be Blessed-God Is The Supreme Truth).